[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

Wichita, KS

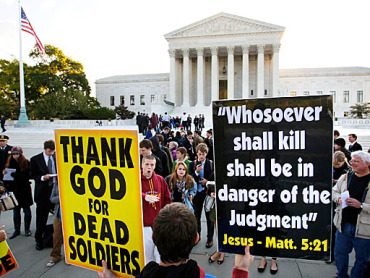

Here in Kansas, we are unfortunately very well acquainted with Topeka’s own Westboro Baptist “Church” (I put “church” in quotes because whatever their actual name or legal status, what they clearly are is a small, inbred, weirdly self-aware yet profoundly pathetic cult). State Democrats and Republicans alike have been active in trying to shut down or at least place limits upon the church’s ability to conduct ugly protests at and around military funerals and other public–and often personally solemn–occasions, and their actions were joined by national politicians on both sides as well yesterday, when Reverend Fred Phelps and his tiny, deluded flock came before the Supreme Court as part of the case Snyder v. Phelps. But of course, once a case reaches the highest levels of the nation’s judicial system, questions of police barriers and respectful distance and all the rest of the matters which have been subject of legislation, though still relevant, shrink in importance; what matters, ultimately, is the interpretation of fundamental constitutional principles: does the First Amendment protect protesters at a funeral from liability (Snyder won an award of nearly $11 million in punitive and compensatory damages after suing Phelps and Co. for picketing near the site of the funeral for Snyder’s son, who dies while serving in Iraq) for intentionally inflicting emotional distress on the family of the deceased? Or, in other words, does the First Amendment provide cover for pretty much any, perhaps even all, emotional harms?

It’s a given that nobody, I mean nobody, likes or agrees with what the WBC people choose to do. (Their appearance at the Supreme Court yesterday, complete with their ridiculously inflammatory signs and claims, was, by all accounts, a scary, perverse circus show.) But given the scholarly and institutional forces reluctantly lined-up on behalf of WBC–the American Civil Liberties Union, The Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression, most major media companies and outlets, and more–and given that this (in many ways obviously “conservative,” whatever that may mean in this case) court nonetheless recently ruled 8-1 that prohibitions of graphic and offensive videos of animal cruelty are protected by the First Amendment, I think it rather unlikely that WBC will lose this case. Which frustrates me, because I’d like to see them–and the great majority of their First Amendment absolutist supporters–get seriously spanked.

Dahlia Lithwick, whether you love or hate her thoroughly opinionated reviews of Supreme Court arguments and decisions, is a tremendous judicial reporter. She notices things which so many others miss. But in her coverage of Snyder v. Phelps, she couldn’t see what the overwhelmingly majority of people of her class and profession and outlook also don’t see: that speech–and I mean here, specifically, the individual right to express themselves–is, frankly, only a second-order good, not a primary one. After insightfully detailing the oral arguments, she sums it up pretty simply: people are being caught up in the fact that what WBC does is hateful, and hate is not to be trusted; it gets in the way of the basics. “They are struggling here with the facts,” she concludes, “which they hate. Which we all hate. But looking at the parties through hate-colored glasses has never been the best way to think about the First Amendment. In fact, as I understand it, that’s why we needed a First Amendment in the first place.” This is not an unusual conclusion; it’s a standard liberal, individualist, pluralist one. Adam Cohen repeated it in Time Magazine: “it is important for the court to rule that this kind of expression lies within the First Amendment. We defend it not because these ideas are particularly worthy of being protected, but because all ideas, even the most loathsome, are.” Or forget today’s journalists; just go back to John Stuart Mill: “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind” (On Liberty, chp 2). Start tossing around that kind of language, take it absolutely seriously, and the result will be…well, among other things, it will be Supreme Court decisions like Federal Elections Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, or the notorious Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, in which speech–your right to say it, your right to buy it, your right to hear it, your right to sell it–is considered essentially sacrosanct, irregardless of the emotions–or the inequities in power and access–involved. Comfortably liberal commentators like Lithwick may not see the connection between defending a fundamental right to speak offensively and defending a fundamental right to all the advertising anyone with deep pockets can possibly buy, but the connection is there. Which is another reason why this court will be unlikely to side with Snyder against WBC’s hate. Too bad.

I’m not attacking the First Amendment here; I simply disagreeing with one particularly common, frustratingly extreme way to interpret it. Defenders of current law can, of course, come forward to point out the many exceptions and further considerations that might complicate my wish. It is true that we have a variety of precedents, restricting speech when a speech act poses a burden upon the necessary, ordinary business of others, or when it presents a threat to the preservation of public order through inciting violence or intimidation. But this case doesn’t involve any of that; it involves someone claiming emotional harm due to the speech (which, it must be said, he only learned about after the fact through television reports; local laws prohibited the Phelps from carrying their signs into the funeral home or along the funeral procession route). And the fact remains that the law, and very likely the Supreme Court, just won’t take “hate” or “emotional distress” seriously as a good worth defending, or at least worth balancing against the imperative of defending even loathsome opinions. But they should.

The basic argument is one of pluralism, and defending minorities. If someone can sue another person for ruining their day by claiming that they’re a fag, a slut, or whatever, then doesn’t that give those in possession of majoritarian understandings of those terms enormous financial power over those who are not? Possibly. Or, then again, possibly not. Wouldn’t it be reasonable to argue that the pluralistic world of opinions in which we inhabit isn’t, in fact, one single uniform undistinguished marketplace of ideas? That, perhaps, some arenas of action and expression, both spatial and temporal, aren’t actually quite part of the public square? The truth is, of course, that we already accept and acknowledge that fact; this is why church’s are allowed to own property from which they can ban certain acts of speech which they find offensive to the beliefs they promote and contrary to the peace of mind of those who attend that church. Why can’t funerals–and I don’t just mean the actual graveyard; I mean the whole mediated environment within which a funeral is conducted–be similarly seen as property isolated from the vigorous expression of individual opinion? Because, to do so, would be to invest public space with some sort of meaning…some definition of the good? As in something like this:

The process of burying one’s dead partakes of a space and activity that have a meaningful purpose, a purpose which includes the emotional wellness of the bereaved, but also the social benefit which comes through such respectful bereavement; this is exemplified by, among other things, the respectful treatment graveyards receive when city planning takes place, the fact that we countenance police involvement as escorts for select funeral processions, and indeed the respectful behavior of motorists in pulling over or slowing down as those processions go past. As those emotional and social purposes are undermined by those who would use the occasion of a funeral to attract attention to their particular ideas, it would be wise to limit the applicability of First Amendment protections to those would engage in such disruptive or even just demeaning actions in these kind of spaces. The claim that funerals, by being announced in news outlets, therefore involve “public figures” regarding whom different constitutional rules apply is silly argument–the whole point of the funeral is for the public body to make possible and thereby experience, even indirectly, the good which bereavement provides to the whole. Surely most public figures, and most public paces, should be open to diverse individuals’ exercising the full range of their protected First Amendment rights…but not all of them should be.

Could such language come from Chief Justice Roberts? I doubt it. Maybe from Scalia, but even there I don’t think so; he and Thomas may like playing around with natural law and originalist ideas which don’t hold with Millian liberalism, but in the end what I’m asking for here is something significantly more communitarian and Aristotelian than our current constitutional order is likely to be able to admit. And I don’t know: will that likely result make me despair, make me think that, once again, the primary of the individual, and the abuse and inequality and alienation which that frequently makes possible, has been wrongly defended. Perhaps a little bit…but overall, I’m a member of a liberal society, and being liberal–being respectful and careful when dealing with the many differences and points of potential conflict between individuals, and trying to treat them all as fairly as possible along the way–is a good things to be. I just don’t think it’s the best thing to be, not in all cases, not even in most cases…and at the very least, when it comes to funerals and the feelings of those who are putting loved ones into the ground, certainly not in this case. There are higher, better, more meaningful, more communal goods available in this case. Would giving priority to those goods in Snyder v. Phelps open up oppressive possibilities in the future? If we were talking about the heavy hand of the state, then I’d consider that a possibility (by no means an obvious one, but a potential one, I agree). But we aren’t actually talking about that; we’re talking about torts, and damages, and the rules allowing for such. Some people will not find their bereavement harmed by offensive lunatics making asses of themselves 50 yards away. But some might. And maybe bereavement is an important enough good that, in such cases, the community ought to let the laws serve the interests to those being targeted by ugly speech, rather than those doing the speaking. After all, in an attention-driven 24-hour media environment, they will likely always be able to speak more than enough.

36 comments

Anonymous

The westboro babtist is not a “church”, it is a hate group. They are in it for the money and the press. Most of the members of this “church” are attorneys. If any other group showed up at your door, would they get away with this? No! Why do they? Any one can say they are a “church”, that is not going to make you a Church! We in this country let a lot pass for “church”. This is not about freedom, it is about being human. The hate is a way to make money, by bringing a Lawsuit against people THEY have provoked. They are running a “church” scam.

Russell Arben Fox

Siarlys,

I agree with John: you make a solid, fair case for seeing existing First Amendment law as something which ought to still allow certain punitive responses to those who wish to defend themselves and their own spaces against the intrusion of hateful speech. I hope the Supreme Court issues a decision which follows your reasoning–in part because it is far more likely than the decision I would prefer, and in part because it would be far superior to the decision (a slapping down of the Snyders) which I expect. I would ask one question, though. You write:

But, when he targets a particular private individual (definitely not a public figure), there is no good reason that suing for intentional infliction of emotional distress should not apply.

I wonder, exactly how much distance–theoretically, legally–is there between granting that private individuals may have recourse to lawsuits (which will have the indirect consequence of making certain sorts of speech less likely and more difficult to get away with) to respond to hateful speech expressed in a targeted fashion, and granting that a polity may similarly choose to impose punitive burdens (in the form of, say, broadly interpreted and enforced disturbance of the peace ordinances) upon speech acts which “target” particular places…like, say, military funerals? I’m genuinely curious. Maybe the distance between the two is massive; maybe it isn’t. Your thoughts?

John Gorentz

Ooh. Forgot to say what I meant to say about the taxing of churches. Property taxes are the main taxes I care about when I say churches should pay them. There are too many churches who are unwilling to take a course they think right (whether it is right or wrong) because they stand to lose their property if they leave the larger organization. And the larger, established, property-owning organizations tend to be the ones that have their interests aligned with those of the political establishment.

Yesterday I rode my bike through Amish country in northern Indiana — past several scenes where unhitched buggies were parked outside a home. Amish people worship in homes. Each congregation has worship services every other week. In the alternate weeks they visit friends and relatives and worship with their congregations. It’s a community building exercise that’s possible only where church property isn’t a millstone around their necks.

So I suppose any church could do that without any changes in the laws. (Well, there are residential zoning laws.) But the whole world of non-profits has become corrupted and has become an appendage of the state. Income and property taxes would help break up that unholy relationship.

John Gorentz

Siarlys,

I hope you don’t mind my presuming to commend you for making the best case I’ve heard so far for the Supremes to allow the jury verdict against Phelps to stand. You’ve convinced me, at least until someone comes up with a counterargument that could overrule yours. Not likely, I would think.

It helps that not only do you make very careful distinctions, but you also don’t seem to be one of those people who are looking for an excuse to begin open season on the First Amendment so they can kick butts and stifle the speech of people they disapprove of.

Siarlys Jenkins

I’m a First Amendment purist, but I’ve been looking at how we COULD apply and expound on the amendment in such a way that Fred Phelps gets what he deserves, without, as Stevens wisely points out, restricting speech we all agree should enjoy First Amendment protection. I’m basically with Hugo Black that when it says “Congress shall make no law,” it means Congress shall make NO law, although I’m not quibbling over shouting fire in a crowded theater.

If Phelps and his gang were to appear in the public square somewhere in the town where a funeral is going on, he would, I’m pretty sure, be on solid ground as far as the First Amendment is concerned. But, when he targets a particular private individual (definitely not a public figure), there is no good reason that sueing for intentional infliction of emotional distress should not apply.

That civil action is what the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals denied to the Snyders. It would require no new law to allow the jury verdict against Phelps to stand. There is, for example, the precedent of Guinn v. Church of Christ of Collinsville, 775 P.2d 766 (Okla.1989).

Church leaders threatened to broadcast to the congregation the plaintiff’s sexual relations outside of marriage unless she repented. Guinn withdrew her membership in the church and hired an attorney who advised the church not to mention her name in church. They did anyway. Guinn brought suit for invasion of privacy and intentional infliction of emotional distress. The Oklahoma Supreme Court rejected the church’s First Amendment defense, finding that Guinn had effectively withdrawn from the church and was no longer subject to internal church discipline.

(I ran across Guinn some years ago, in an excellent Tenth Circuit case, Bryce v. Episcopal Church, 289 F.3d 648, laying out the doctrine of church autonomy in matters of faith and doctrine, ruling that an internal church discussion on homosexuality was not actionable in a Title VII action by a dismissed youth pastor after she married Rev. Sara Smith. The Guinn case had been raised by the plaintiffs, to no avail. But the Snyders are not involved in an INTERNAL church discussion at Westboro, on matters of faith and doctrine. Like Guinn, and much more so, since she had once been a church member, the Snyders are private individuals being targetted BY Phelps.)

How would such a ruling infringe my First Amendment rights in some cascade of unintended consequences? I can’t think of any. A borderline case might be, if I wanted to picket Chelsea Clinton’s wedding, is SHE a public figure? Or only her father? Could I picket HIM when he arrives without inflicting emotional distress on her? Is her wedding a matter of public concern anyway? Don’t forget, there is already well established precedent that if you are at work, speaking on a matter of public concern, your employer may not intimidate you i the exercise of your First Amendment rights, BUT, if you are talking about anything else, your employer may enforce a policy that “you should not say that on my premises,” particularly if you are talking about company business.

Could I show up at Fred Phelps’s funeral with a big sign saying “God Has Spoken,” or a more biting Biblical quotation? Maybe not == or maybe, since he’s made himself a public figure, I could. Undoubtedly Phelps has a First Amendment right to picket outside the base where the flag-draped coffins arrive from overseas. But the Snyders did not make themselves public figures. It is the act of targeting a funeral, with the undoubted intention to inflict emotional distress, that is a valid civil tort.

————-

Separately, a brief note on taxing churches: I favor abolition of “tax-exempt” status, but that doesn’t mean voluntary contributions to a common cause, or a church, would be taxable as INCOME. They are not wages or profit. What would change is, donations would not be deductible from the DONOR’s taxable income. If a church runs a business, that income is already taxable as such. Whether churches pay property tax, I don’t much care either way.

John Gorentz

The very reason churches should pay taxes is to maintain their independence from state-approved standards of “enlightenment” and “service.” But all non-profit organizations should pay taxes, not just churches. We’re all in this together, and we should all pay. If taxes are too high for the local non-profit homeless shelter to be able to do its work, then taxes are too high and we should all work together to do something about it.

Russell Arben Fox

Matthew, thanks for the kind and thoughtful comments (especially the point about how “informal, extralegal guarantees and institutions” need “some level of formal recognition” by the state; I agree, and find how you put it very well said). However, I should note that I brought up the example of churches and taxation in order to ironically make the complete opposite point from the one John (and Dan) seemed to be making. I really do think that “the articulation of goods” shouldn’t depend upon one’s ability to raise money and purchase property. Do I believe it should be as “free” as the right of individual expression? Probably not. But there are good historical, communal reasons why churches and other types of faith-based organizations have been granted, shall we say, “assistance” in their protected ability to diversify and enlighten the public square with their messages; as a believer in the value of civic religion, I could hardly think otherwise.

Matthew F Cooper

Russell, excellent piece. The topic of free speech is a troubling one to discuss, and one can hit a lot of landmines in doing so, given how sacrosanct an extremely broad interpretation of free speech has become in the popular understanding of American civics. I’m glad you’ve been willing to brave that ground in order to present a dissenting view, particularly in a case such as this one where the WBC can do a lot of harm to the families of soldiers who have been killed.

Caleb, I appreciate your careful distinction between the use of formal and informal institutions to discourage the antics of the WBC – in some ways, I think it is admirable. You may be right to assert that a statist view will seek first to reify informal institutions through the use of state power, and you are certainly right to insist that when governments coopt informal norms for their own purposes they can distort both the basis for those norms and the incentives for proper behaviour under those norms. However, I think it also needs pointing out that informal, extralegal guarantees and institutions cannot maintain a healthy existence without some level of formal recognition or at the very least acknowledgment of space by the state. If state and civil society are completely divorced, we end up with the two running in dysfunctional parallel (for example, the Mafia). A more complete communitarian perspective would have to realise the need each has of the other.

John and Russell, I am in absolute agreement with you that churches and other houses of worship should pay taxes – though perhaps some exemptions can be made based on the services they provide openly to all members of their surrounding communities (and not just to their parishioners).

John Gorentz

Yes, Professor Peters, I’m in Michigan. Some years ago one of the PhD candidates at my workplace decided he didn’t want a doctorate in microbial ecology; he wanted to brew beer. So he went off and helped start one of the local brewpubs. I think he’s still in the business. I’m not much of a beer drinker myself, but my wife and I have made the rounds of the local brewpubs, usually with our kids. I think the products are all too sweet. When I drink beer I like it bitter, otherwise what’s the point? And I like it at room temperature, rather than cold enough to kill the taste. (When I’m out with them I try to shut up and enjoy it for what it is. I am not always completely successful at that. But since you gave the order, I guess I’ll have to do my duty and try again.)

The very best fruit wines on the planet are made at a nearby winery. When I want sweet, that’s what I want.

If your department has diplomatic relations with the biology department, say hi to Kevin Geedey for me. I will try not to hold it against you guys that you’re occupying Black Hawk’s space.

Jason Peters

Mr. Gorentz, you’re in Michigan? Lucky devil! Hit a brewery for me. Dark Horse or Old Hat or Bell’s or MBC. I don’t care which. I’m like Klinger pining for Toledo. Except Toledo can go bugger itself. It’s Michigan I want!

John Gorentz

Yes, churches should pay taxes like everyone else. The power not to tax is the power to destroy. Churches shouldn’t be in that kind of relationship with the government.

As for your jabs at individual rights, I would argue that governments that limit individual rights such as free speech and the other 1A rights (not only because the power peaceably to assemble is among them) are likely to create a type of individualism that comes at the expense of communitarianism. Also, the right not to be offended can only be granted by giving huge powers to the central governments, powers that go well beyond those that are needed to protect the rights that are enumerated in the U.S. bill of rights.

Russell Arben Fox

Dan,

Freedom of speech is free, freedom from speech costs money.

Interesting. I take what I think to be your broader point–that there are already precedents in place for community-minded individuals and groups to establish spaces of “appropriate” speech, as they understand it–but I find myself deeply troubled by the implications of your conclusion. So, the expression of rights get a free pass, but the articulation of goods depends upon your ability to raise and control capital, eh? I wonder how many folks around here really would follow that line of reasoning all the way to the end. For that matter, I wonder if the United States follows it, considering the tax-exempt status of churches and charitable organizations. Man, with those places forcing out the gay-rights protesters trying to break up Mass–shouldn’t they have to pay taxes like everyone else? If they want freedom from speech, they ought to pay for it like every property-owner.

Ethan,

See what I said about about Chaplinsky and “fighting words.”

Alex,

But government enforcement of community standards, with those community standards decided upon by that same government? That’s what you are arguing FOR? And at a federal level, no less?

No, that’s not what I’m arguing for. What I suggested above, as I thought I made clear (though perhaps I didn’t), was written in the context of the actual case currently before the Supreme Court. Which means, in essence, that I wouldn’t mind seeing the Supreme Court lay down such parameters as would allow people like Snyder and his loved ones, engaged in the process of burying their dead, to extract damages, should they so choose, from WBC for their hateful, disrespectful, and harmful-to-the-public-goods-of-bereavement actions. Would such have a chilling effect on funeral protesters? Of course. Good. Maybe that’s a clumsy and dangerous way to go about bringing communal concerns into the argument; maybe it would have been better if, as Caleb and others have insisted, everyone had just followed the Topeka model and found “extra-legal” ways of treating WBC as a joke. The part of me that is suspicious of the Supreme Court and the undemocratic, centralizing, rights-centric powers it enjoys agrees fully with that. But then again, Snyder v. Phelps is right there, on the docket…and considering that I think it likely the SC will basically issue WBC an official FA-approved Get Out of Jail Free card, I’d rather take the risk of the consequences of my idea than see another brick added to the already too-high Liberal Individual Rights Trump All idol which we tend to worship at.

Alex E.

Mr. Fox, I feel your pain. But government enforcement of community standards, with those community standards decided upon by that same government?

That’s what you are arguing FOR? And at a federal level, no less?

Would you let anyone else get away with arguing for that, if they didn’t pick your pet issue to base it on?

We are not all one community, with a single set of community values. I’d rather my neighbor was allowed to say what is offensive to me, as long as he can’t keep me from saying what’s offensive to him.

Ethan C.

See, what really bothers me is that the WBC’s speech doesn’t “[present] a threat to the preservation of public order through inciting violence or intimidation.”

I would think in a healthier culture, it would. Every single time.

Dan Weston

Russell, your “communitarian philosophy translated into practice” is already here: homeowner’s associations, private cemetaries, churches.

The Supreme Court has already upheld the right of homeowner associations to forbid the display of flags and to otherwise limit the rights of speech, property, and association (except for suspect classes).

Don’t want Phelps at your funeral? Be buried in a fenced-in private plot and play loud dirges to drown him out. Don’t want to see a U.S. flag being burned outside your house? Live in a gated community where exterior fires are not permitted. Offended by the color pink? CC&Rs is your friend. Offended by gay people? Stand next to Phelps and shout (yes, this is still your right). Gays have a thick skin. There is no constitutional right to being comfortable.

What you are really looking for is a free handout, the majority’s taking of minority rights without paying for it. Freedom of speech is free, freedom from speech costs money.

Russell Arben Fox

I confess that I’m surprised at the large number of fairly (if not absolutely) firm defenders of the First Amendment I’m finding here. Maybe I shouldn’t be, and of course it’s always good to have one’s assumptions challenged. But still, it has long seemed to me that a firm defense of individual or group self-expression, one that is accepted as a right operable in essentially any context, has been at least as damaging to the spirit of civility and locality as any number of other socio-economic centralizations. Prayer in schools? Opposition to pornographic establishments? Flag burning? In these and other matters, a context-less devotion to a neutrality-obsessed First Amendment has forced disruptions of local traditions and broad community consensuses, which are one of the key requirements of a civil life and hence are the sort of things that I would assume most FPRers would want to conserve. Thus, my surprise.

Still, A.W.’s point is a strong one, and I can’t just wave it away. It’s interesting to imagine how I would like to see my communitarian philosophy translated into practice, but can it actually be done? Perhaps not–and not just because our national tradition of jurisprudence works against it, but because made it’s just not conceivable in a pluralistic society. I wouldn’t want to give up the argument yet, though: for example, A.W., any attempt to work through your example and my suggestion might result in some productive thinking about “virtual” vs. “non-virtual” speech–even if Snyder learned about WBC’s gross actions via a subsequent television report, the fact remains that there were actual persons engaged in actual acts of disruption, as opposed to someone vomiting hate on a blog post, which exists exactly nowhere in space or time. Still, maybe that thinking wouldn’t go anywhere, and yes, you do still have to think about the practical big picture of precedent, so thanks for that reminder.

Caleb, I’m still curious about what, exactly, Topeka has done to prevent WBC from being more than “an annoying gnat buzzing around.” And I guess the sometimes-statist in me is wondering: have those actions truly been entirely “extra-legal”? If so, does that mean you’re talking about other things besides 2007’s Kansas Funeral Privacy Act? Is that also an example of the power of the state which you oppose, or are you okay with it, seeing as it was a state, not a national, body which produced it? If so, then our argument returns to familiar ground: we’re not really arguing about the sometimes (I agree, not always…but sometimes) legal requirements of maintaining community and civility, we’re just arguing over which community ought to able to intervene in such things.

Katherine Dalton

I’m with Caleb and the Stegallians on this one. Some things–essential civility for one–cannot be legislated, and no law is going to help the Snyder family restore the funeral that is past and gone. And while I am glad I am not surprised to find that Topeka, KA has found a way to marginalize this group. Some decencies are still defended, and we can take some small encouragement from that.

But when First Amendment protections for political speech go–and they are going–I will miss them.

John Gorentz

Excellent point by A.W. Stevens about the extreme difficulty in coming up with a single rule to do only what we want without bad side effects. To see how far things can deteriorate in the case of protecting people against emotional distress, and how quickly, look at what has happened in Ukraine. After the latest elections, the western media were going tee-hee-hee over the fisticuffs and egg-throwing in the parliament and were asking silly questions like, “Will Ukraine now have better relations with Russia?” thus averting our attention from the nature of the authoritarian regime that took over. The following is a quote inside an article by Douglas Muir at A Fistful of Euros:

Sounds noble, doesn’t it? Protect people from emotional distress by requiring their permission to have anything written about them.

(Another time I would be glad to eviscerate A.W. Stevens’ notion that this is about practicalities, not philosophy, and that his approach to the question, however excellent, is the only valid one.)

A.W. Stevens

Nope. See, this is the problem with non-lawyers running their mouths about this stuff. It’s not that y’all don’t understand the constitution, it’s that you don’t understand how binding precedent is applied by lower courts.

Put aside all the fancy language about how the worst ideas are the ones in most need of protection… if one person is silenced we all are… blah blah blah. That’s not the point. What matters is this question: Can you come up with a rule that restricts Westboro Baptist’s speech, but does not also restrict speech that we all agree should enjoy First Amendment protection?

I can’t think of such a rule, and from what I’ve heard about the oral arguments in the case, neither could any of the justices.

Russell, just as an example, under the rule you proposed, what if someone posted something derogatory on an internet message board about Timothy McVeigh right after he was executed? Should McVeigh’s relatives be able to sue over that? The speech could certainly be seen as interfering with the “process of burying one’s dead.” Granted the speech was not made at the physical location of the funeral, but so what? The Westboro people weren’t at the grave-site either.

This isn’t about philosophy, it’s about practicality. Just as we all find the speech in the Westboro case offensive, there is all sorts of speech out there that we all agree is legitimate, and unless you can find some way to gag the former without ushering in a wave of lawsuits concerning the latter, you’re not adding anything useful to the discussion.

D.W. Sabin

The essential problem with accumulating remedies is that the side effects will kill you. At the very least, the side effects will be far worse than the original affront.

Caleb Stegall

Russell, some quick google searching on Scalia and positivism should lead you to good resources. Also, you need to read Scalia’s famous law review article “The Rule of Law as the Law of Rules.”

John, you’re welcome. It is indeed a vital distinction, and one we too often fail to give sufficient attention.

John Gorentz

It’s hard to express how pleasing it is to find that a Front Porcher truly knows how to be communitarian, and understands the difference between communitarianism and statism. Thank you, thank you, Caleb Stegall. You’ve just made the fall colors seem a little brighter here in SW Michigan.

Russell Arben Fox

You make me curious about Scalia; I’m going to have to do some poking around regarding the connections between his opinions and positivism before I teach Con Law next semester. As for punitive consequences that do not partake of civil judgments, what are you talking about? Social ostracism? Newspapers refusing to accept their advertising? Please share; I’d really like to know.

Caleb Stegall

Scalia is absolutely a legal positist (though it is not surprising you haven’t heard him refered to this way, because the portrayal of him in the general media is pretty ignorant … but a quick review of the scholarly liturature will show that he is widely recognized as the leading positivist on the court … a view that happens to be shared by the most recent addition to the court) which admittedly traces roots more to Bentham than Mill, but still …

I agree that dissent should risk punitive consequences, and WBC has endured all kinds of punitive consequences here … those consequences just shouldn’t be imposed by the state or by individuals utilizing the power of the state, which is exactly what a civil judgment is.

Russell Arben Fox

Caleb,

I’ve never heard Scalia referred to as a “positivist” before, and I think he would vehemently deny any linkage between his thought and Mill’s (his dissent in Lawrence v. Texas would be his first bit of evidence there). I agree, though, that it was lazy of me to lump Scalia and Thomas together, as the latter’s explicit invocation of natural law jurisprudence far outstrips Scalia’s occasional references to it. As for your general point, I take it, but I actually wonder how it applies to the case at hand. I’ll take your word for it that “Topeka has done a very good job of utterly marginalizing WBC in all kinds of solid, communal, extra-legal ways that did not and do not depend on the power of the state.” I would ask, then–would one of those “solid” methods involve an individual or group being able to sue WBC for emotional harm? Because that is, fundamentally, what we’re talking about there: whether an obituary in a newspaper makes you enough of a “public figure” that the First Amendment should protect you from all power of torts. That seems to me to be something that the government cannot help but be obliged to rule upon.

I also absolutely agree with your that “every healthy community also requires at least the possibility of real and true dissent,” and I don’t want to open the door to some sort of denial of that fact. However, does every healthy community also require that said dissent be essentially free from punitive consequences, so long as it happens in particular times and particular places, regardless of what the “dissenting” message may happen to be? What do you think?

Caleb Stegall

Scalia is a positivist not a proponent of natural law. In that sense, he may be the most Millian justice there is. Regardless, it’s a mistake, though common, to lump Scalia and Thomas’s jurisprudence together, when in fact they are dramatically different.

And for the record, I’ve seen the power of the state deployed to intimidate and limit opposition too often to not be a first amendment absolutist. The basic problem with your approach here, Russell, is that it is an attempt to vindicate and hedge community standards with the power and apparatus of the state.

Communities have all kinds of extra-legal (not illegal) ways of policing and circumscribing speech that violates their standards of decency. As one old English jurist put it, the common good is absolutely dependent on “obedience to the unenforceable.”

It is true that many communities suffer from frustration and worse when they find themselves subjected to a recalcitrant and resillient speech dissident in their midst (such as Topeka has suffered from the Phelpses), but truth be told, Topeka has done a very good job of utterly marginalizing WBC in all kinds of solid, communal, extra-legal ways that did not and do not depend on the power of the state. WBC is a joke in Topeka now, and really doesn’t much bother anyone. At worst, they are an annoying gnat buzzing about.

Let communities deal with dissidents in this way … keep the power of the state out of it, because every healthy community also requires at least the possibility of real and true dissent.

John Gorentz

I’d hate to see an exception carved out for funerals, because I was kind of hoping I’d live a worthy enough life so that when I die the leftwing fascists who are coming to dominate our society would be out in full force, lining the streets to say good riddance, wish me a hot journey, and chuck an occasional egg or tomato at the hearse. I have a lot of work to do in a short time if I’m going to live to see that, but if you’re going to make it illegal for them to protest, there’s not much point.

By the way, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin also thinks that free speech is a second order concern. He, too, puts communitarian interests ahead of free speech. Life insurance premiums for journalists in his country have got to be horrendously expensive.

Rachel Blum Spencer

Dear Russell,

I’ve been puzzling over this, and enjoyed your perspective. I was wondering, though, what you think of counsel for petitioner’s argument that an exception ought to be carved out (as the Supreme Court has done before in free speech cases) for funerals, especially those of private figures? The analysis I’ve heard seems to concur that this was a weak argument, but it does nonetheless seem to be a common decency sort of argument, or maybe a “prurient interest” line of argument (which the SC adopted in the majority opinion about pornography a while back). Was the line of reasoning from Miller v. California an example of what we could call first-order concerns (some sort of concern about morality and children) making its way into jurisprudence and outweighing the second order concern of free speech?

Russell Arben Fox

Roger,

Perhaps an alternative to suing them for liable would be to make mourners who committ assault and battery on a protester immune from civil and criminal liabilities. That is of course a joke but it might fix the problem and it is pleasing to think about.

I actually sometimes wonder if that idea wasn’t what the court was originally playing around with in the Chaplinsky decision, decades ago, when the idea of the “fighting words” provision in First Amendment law first emerged.

Chris,

I agree with you that Citizens United went much too far, and I do think that you can be critical of that decision without rethinking our whole focus on an individual right to speech, as I suggest in this post. I suspect that a real absolutism regarding speech makes it harder to address the (I think incoherent) claim that corporations have free speech rights too, but it’s not impossible.

WmO’H,

I can see your point, but I’m not (yet) persuaded that it is actually a valid concern. I hear a lot of noise about lawsuits and citations arising from “hate speech” accusations made against traditionalist Christians, and surely those do have a real chilling effect, but still, I have yet to hear of any of those lawsuits or citations actually resulting in fines and jail time. If such has really happened somewhere, please share.

WmO'H

I’m afraid that a decision in favor of Snyder in this case, although agreeable to all of our moral senses, would be extremely bad precedent for a group of people (religious conservatives) who within a not-so-distant future will espouse what might easily be construed as hate speech.

Chris White

Much as I abhor both the content and choice of time and place chosen by the WBC to exercise their right of free speech on a moral/political topic, I believe the First Amendment is on their side. Similarly, I disagree with the view and tactics of those who speak out against a woman’s right to choose by protesting outside clinics and Planned Parenthood offices with signs showing aborted fetuses while (however reluctantly) accepting that they have the First Amendment right to do so, regardless of whether they cause emotional distress to women who might have appointments at those clinics or offices. I do, however, think that the SCOTUS decision in Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission went too far in accepting the status of corporations as being legally equivalent to individual citizens. That is an area of legal precedent that needs to be revisited and revised.

Roger S.

I share your frustration Russell. They never rule the way I think they should. Apparantly the issue is not over whether one can regulate the time, place and manner of speech. I think the government can do that to a very limited and narrow extent. (no right to yell fire in a burning theater). The question is can someone sue and recover damages if the speech causes emotional pain and suffering. When it applies to the nut cult involved here, I certainly favor the idea that perhaps some liability for the speech one is free to utter might actually hone our freedom and make it more meaningful. Perhaps it would make civil discourse actually civil. On the other hand I hate to think that I expose myself to liability by calling this group a nut cult. I like calling them a nut cult along with a few other choice names. Perhaps an alternative to suing them for liable would be to make mourners who committ assault and battery on a protester immune from civil and criminal liabilities. That is of course a joke but it might fix the problem and it is pleasing to think about.

Russell Arben Fox

John, Roger, I agree with your both. I’m enough of a small-d democrat that I’m not entirely sure I even like having a Supreme Court; at the very least, I do think that judicial review and other powers that have the Supreme Court and the judiciary in general have accumulated over the past couple of centuries have not been good for genuine community life and government. But that being said, we do live in liberal society, and that means having some body to oversee how liberties are understood, enforced, or restricted is probably inevitable. In that spirit, I would like it if they ruled in my favor, some of the time. I don’t expect a sudden communitarian conversion that will allow the Court to see the validity of the complaints about Westboro Baptist which have been brought by numerous states, not to mention veterans organizations and the like, but I sure wouldn’t mind it if it came to pass.

John Gorentz

It’s not just the Supremes. Google for ‘court “handed a victory”‘ and you’ll see that that kind of talk is used on courts at all levels.

Roger S.

I agree with you John but the Supreme Court is much to blame for how it is portrayed. More and more it’s members seem to vote down party lines and to that end, it is hard, even for the idiots that report the news, to miss it.

John Gorentz

The job of the SC is to rule on the law, not kick butts. I’m getting tired of politicians and news headline writers who talk as though the SC rules in favor of this or that party, or “hands a victory” to this or that faction. That’s not what what the Supreme Court, or any of the federal courts, or any court at any level, is supposed to do. We just encourage bad behavior on the part of the court system if we routinely talk about it that way.

Comments are closed.