If we expect others to rely on our fairness and justice we must show that we rely on their fairness and justice.

—Calvin Coolidge

My wife and I recently vacationed in Florida. One morning, over a cup of coffee and a doughnut, sitting on the balcony and reading a newspaper amid seagulls and the grating roll of morning waves, I noted that one Michael Stone—a blind man, XTERRA champion, and 10-time Ironman triathlete who recently published a book, Eye Envy—was to speak at the University of North Florida. I haven’t read Stone’s book, but it’s apparently a resource not only for those suffering from vision loss, but also for those suffering from any degenerative disease.

Stone began to lose his sight in 2004. His blindness is a result of a rare disease called cone-rod dystrophy. Despite his handicap, he has accomplished amazing things, but not without the help of others. During races, Stone relies on guides, who, the newspaper explained, shout directions and warnings to him. Without this guidance, Stone might not be able to race.

I’ll never understand why God makes some people handicapped and others not, why some must rely on others, and some must be relied on. Like everyone, I have my theories. But they’re just theories. The important point, though, is that someday and for a time, everyone relies on someone or something and is relied on by someone or something.

In graduate school, I took a class on Shakespeare. One of my peers was deaf. I always wanted to ask her what that was like, but knew that I couldn’t, or shouldn’t. And she, the deaf student, wouldn’t know what it was like. Not really. Because she didn’t know what it wasn’t like. She’d never heard sounds before, at least not the way I had. She had interpreters, and I always wondered how Shakespeare’s Early Modern English translated into hand signs and symbols. Every now and then another student would read a passage or recite some lines, and the deaf student, not knowing which lines were being read or recited, had to rely on her interpreter to gather meaning. I wondered how, with a split-second to think, an interpreter could sign such words as “Cry to it, nuncle, as the cockney did to the eels when she put ’em i’th’ paste alive. She knapped ’em o’th’ coxcombs with a stick, and cried ‘Down, wantons, down!’”

We all, deaf or not, have limitations. By helping one another, we limit limitations, both our own and others’. There’s justice in that.

Sign language is a medium of correspondence that’s physical and, it seems to me, fun. It’s writing in the air. I knew nothing about it as I sat in that class, but I loved it. Here was this system, a spatial grammar and syntax, which I saw once a week for three hours or more, over the course an entire semester, but which I couldn’t learn by watching. It had its downsides. For instance, it drew attention to itself and made others uncomfortable. But it was beautiful.

My professor, a sweet man, tolerant to his own detriment, gave the deaf student carte blanche to do whatever she wanted. He never asked her questions, never forced her to contribute to the group conversations. And what good did this do her, or him? Part of the pleasure of graduate studies is learning to ferret out answers or speculations on your own. There’s something unjust about taking that pleasure away from someone—about not doing your job when someone relies on you.

What, exactly, is justice to the person who has lost her hearing through no fault of her own? What ought to be the role of the one relying and the one relied on, if learning is, as it ought to be, just?

I don’t know.

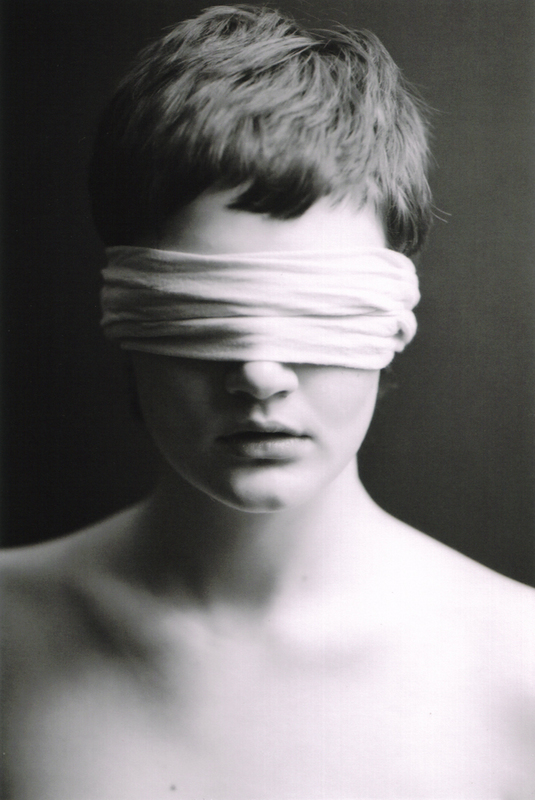

I can imagine being deaf, but I can’t imagine being blind. One of the best essays I ever read on the subject is Borges’s “Blindness.” In it, Borges describes his experience as a blind man, answering questions that the curious, for whatever reason, never ask. “People,” he says, “generally imagine the blind as enclosed in a black world.” But people are wrong.

In fact, Borges explains, the “world of the blind is not the night that people imagine.” It’s actually kaleidoscopic: full of brilliant, undefined colors that may be difficult to distinguish, but that flicker and flash like poems come to life. If that’s true, I understand Homer and Thomas Blacklock and Helen Keller a little more.

The great writers and poets of the past have given us a stock of wisdom and insights that we can rely on to cultivate virtue and to come to grips with life’s complexities. These men and women recorded and enabled beauty and wisdom. Beauty and wisdom are just. It’s also just, is it not, for God to give all of us some form of language with which to express ourselves and to understand others—with which to cooperate.

Folks say that justice is blind. That may or may not be true. But “the judge,” as the townsfolk in Opelika, Alabama, referred to my Great-Grandfather, was blind—although he wasn’t a judge. People just called him that because he was a good lawyer.

The judge was an erudite man who enjoyed an afternoon whisky. He would recite poetry to my grandmother, Nina, when she was a girl. Partial to the British Romantics—Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats—he could also quote from Shakespeare, Irving, Poe, and Emerson.

I still have the judge’s law books. Some of them date back to Reconstruction. Once, while thumbing through an old Southern Reporter, I found a folded, jaundiced sheet of paper—a place marker—wedged between some crinkling pages. On it was a poem by Abraham Lincoln. Nina says that the judge kept a portrait of Lincoln in his office. This, I think, is revealing. Of what, I’m not sure. None other than a brave man would openly admire Lincoln in Opelika during the years leading to and following the Great Depression.

If I should meet the judge one day, after death, I will ask him whether he did not like the milieu in which he lived. I’m sure he liked it as far as things went. He could, after all, know nothing else.

On second thought, if I should meet him, I will ask him to recite poetry. Something from Wordsworth. That would be better. Certainly more beautiful.

Mr. Stone is an inspiration to those who must overcome adversity, which is to say that he is, or ought to be, an inspiration to us all. We’re all handicapped to varying degrees and in ways we cannot control. Whether that’s unjust is hard to say. What is just, though, is being there for those who rely on us. My classmate could not have discussed Shakespeare without her tireless, interpretive intermediary, who made up for my professor’s failure to teach. Borges could not have written without self-reliance, but more importantly without the influence of the great poets and, for that matter, the people who taught him the great poets. My Great-Grandfather, the Lincoln lover, could not have memorized poetry, let alone practiced law, without someone, at some point, guiding him—and possibly without the influence of those same great poets on whom Borges relied.

The world is shot through with language and personal relations, without and in spite of which we couldn’t overcome our handicaps. The justice is in the poetry; the poetry is in the making. On that morning in Destin, as I set aside the newspaper and the sun began to rise over the powdery white sand, which was now populated by families and dashed by the rise and fall of waves, I turned to my wife and told her about Mr. Stone and his triathlons and upcoming lecture. When I finished, she said, “I’m not surprised that he writes.” I asked why, and she answered, “Because we rely on writing to help us understand.”

—

Allen Mendenhall is a writer, attorney, and adjunct law professor. He is the managing editor of the Southern Literary Review. Visit his website at AllenMendenhall.com.

3 comments

Samantha Gilman

A girl I know is blind, but like the deaf student in the article, offers a great deal those around her. We have discussed religion and politics over breakfast, laughed together, and commiserated over the brevity of weekends, as if there was no difference between us.

This article beautifully illustrates the importance of humility – the recognition that handicaps are a human thing. None of us is truly independent. We all fall short of being self-sufficient, and depend on the God-given abilities of others.

God makes no mistakes, and His allowing some to be deaf and blind is His call. Whether our handicaps are about justice or not, it is right that we act toward others with humility and compassion.

Jonathan

Wonderful piece. Very worthwhile read.

Peter

What a beautifully expressed sentiment.

Comments are closed.