This piece was originally published in The Intercollegiate Review.

In 1848 Alexis de Tocqueville wrote of “the approaching irresistible and universal spread of democracy throughout the world.” Since his time the drumbeat has quickened, and with the fall of the Soviet Union the ultimate triumph of democracy seemed inevitable. In his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama argued that liberal democracy really is the final historical step in the development of political thought and practice. The fact that so much of the world today seems either to be embracing democracy outright, or taking faltering steps toward it, or at least paying lip service to it suggests to many that Fukuyama was right, and all that is left is merely a mopping-up operation.

Of course, the smooth highway to universal democracy encountered a serious obstacle on September 11, 2001. It would seem that not all the world shares the same dream. In fact, if the rhetoric is to be believed, the very freedoms that we in the West cherish as essential to a good life are just those that Islamic militants see as the source of Western decadence. With patriotic pride, we instinctively object. But with dispassionate reflection, we can see that the Islamist rhetoric may point to at least a shadow of the truth. If liberty is not directed toward a common good that transcends arbitrary will—even if it is the will of a vast majority—then it eventually descends into a libertinism that is ultimately destructive to society.

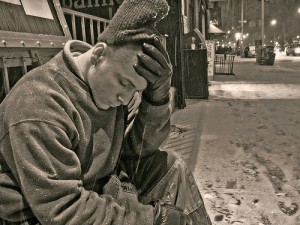

This raises important questions: Is it really true that democracy is a stable system that can, on its own terms, perpetuate its freedoms? Is it really true, as the end-of-history theorists claim, that democracy satisfies our basic need for “recognition”? If so, why do so many citizens in the most democratic society in the world behave as if something is amiss? Tocqueville noted the “strange melancholy often haunting” the Americans. This sense of longing is not explicit and generally has no definite object. It is, rather, an underlying dissatisfaction that today manifests itself in a variety of ways: restless mobility, consumerism, frenzied sexuality, substance abuse, therapy, and boredom.

Read the rest here.

8 comments

Wessexman

Mark your description of Joseph Pieper’s viewpoint on this subject comes very close to the Perennialism or Traditionalism of the likes of Frithjof Schuon, Titus Burckhardt and Rene Guenon(which I share myself.). Of course they would not suggest that Christianity was superior to the other valid, orthodox traditions.

They would say that is not true that rationality, or at least the Platonic Intellect which they are quick to differentiate from discursive ratio alone, is limited by traditions; there must be a timeless objectivity in human views on tradition, the universe and history because suggesting there is not would be contradictory. It is this Intellect, buttressed by reason that shows both the importance of particular religious traditions and there esoteric similarities(which is of course no suggestion to soft ecumenicalism.) It is the Intellect(atma.) which is ultimately the divine spark itself, a reflection of the divine Intellect or Intelligence itself, and what allows us to escape being trapped purely in time and hence to have objectivity. As the Vedantists put it “Atma is Brahman.)

As Schuon puts it:

“One of the keys to understanding our true nature and our ultimate destiny is the fact that the things of this world are never proportionate to the actual range of our intelligence.

Our intelligence is made for the Absolute, or else it is nothing; among all the intelligences of this world the human spirit alone is capable of objectivity, and this implies—or proves—that the Absolute alone confers on our intelligence the power to accomplish to

the full what it can accomplish and to be wholly what it is.1 If it were necessary or useful to prove the Absolute, the objective and transpersonal character of the human Intellect would be a sufficient testimony, for this Intellect is the indisputable sign of a purely

spiritual first Cause, a Unity infinitely central but containing all things, an Essence at once immanent and transcendent. It has been said more than once that total Truth is inscribed in an eternal script in the very substance of our spirit; what the different

Revelations do is to “crystallize” and “actualize”, in different degrees according to the case, a nucleus of certitudes that not only abides forever in the divine Omniscience, but also sleeps by refraction in the “naturally supernatural” kernel of the individual, as well as in that of each ethnic or historical collectivity or the human species as a whole.”

Though there is an underlying esoteric truth shared by all orthodox traditions, a perspective of which gives them their form and which they crysatallise for a particular section of mankind being the collective counterpart to the Individual Intellect(or in other words revelations.), basically every one must follow a valid traditional spiritual path because it is these which provide the necessary supports in terms of doctrine, ethics, symbolism, ritual and community for the individual to cope with the complexities of the spiritual and human journey. Even the mystic who goes beyond the external forms of the particular traditions must start off within one and partially remain grounded in it, he goes beyond form to the formless and not around it.

Howard Merrell

Mark,

Thanks for the thoughtful article. The opening section reminded me of Screwtape’s comment to Wormwood. “An ever increasing craving for an ever diminishing pleasure is the formula. . . . To get the man’s soul and give him nothing in return–that is what gladdens Our Father’s heart.” (Screwtape Letters, #IX) Since this site has a clear political bent to it, often the articles here point to “solutions” that do not recognize the Divine, or the evil which goes beyond the merely human. Thanks for the reminder.

As to the need for tradition, and a healthy respect for its place in establishing what we know to be true a couple of questions:

People come from traditions/communities that hold contradictory things to be true. I have some friends who live in the Andes Mountains of South America who come from a community that teaches that the reason that fair skinned people have more money and stuff, compared to the darker skinned people is because a long time ago there was a tree that had all kinds of good things on it. A squirrel gnawed the tree so it fell. It fell so that most of the good things fell where the light skinned people live. I actually have some involvement with these people. How do I respond to the truth claims based on their tradition/community? Not only do I have to deal with the fact that I regard the history as utterly false, but also the fatalism of the lesson taught by the legend is not only false but counter-productive to helping these people make the most of the opportunities before them.

I have an acquaintance who grew up as an orphan in World War II era Germany. Her community was the Hitler Youth Corp. (I may have the name wrong) If I were her friend at the time, would the proper response be to encourage her to respect the mores of her community?

To put it in a more basic form: If two communities believe precisely the opposite as to a particular truth claim, can both be true? Should we nevertheless, encourage those folk to respect their community/tradition knowing that one or both must be wrong?

Aren’t many of the communities/traditions that ought to be preserved the result of some rebel in the past who abandoned his tradition and built a new community around what he saw to be the truth.

If the gist of your article is–and I think/hope it is–that we have abandoned tradition/community as a means of establishing what is true/good/worth-investing-ones-life-in and we need to give it a place–or a more prominent place–at the table, then I think I can say, “Amen!”

If you are saying that tradition/community needs to be regarded as somewhat infallible, then I have to object–too much of what I hold dear as truth-to-live-by came to me by way of someone who dared to say that his community was wrong.

Again thanks for a thought-provoking article. It was very helpful to me since I’m not familiar with most of the big-guns, or maybe I should say “long swords” to whom you referred. In my defense, though, they weren’t a part of my community.

BTW: Has anybody seen Bob Cheeks. I miss him. I expected that he would have given a Vogelian take on this posting.

Mark T. Mitchell

Howard,

Thanks for your thoughtful response. You are right that traditions can be wrong and some should be jettisoned. The tradition of slavery is gone in America and that’s a good thing. This suggests that there must be a way to adjudicated between good tradition and bad tradition. We do this by reason and appeals to authority (the Bible, for example, is an authority that many use to arbitrate, but the Bible is handed to us in a tradition, so we obviously need to ask: “why is the Biblical tradition authoritative?”). The very act of rationally judging traditions is made even more difficult since the medium of rationality (namely language) is a product of a particular tradition. We need, then an account of tradition that equips us with the tools to judge between traditions AND makes sense of the fact that there is no “tradition-free” zone from which to work. Faith plays a role here. But if it is only faith, then we have tripped into fideism where there is no rational way to adjudicate between competing faith claims. Some people are content to stay there. Others argue that, despite the fact that there is no tradition free inquiry, we can (as we must) begin with what we have and move out from there. If our tradition has the capacity to explain the world satisfactorily, then this is evidence that it is true. Furthermore, as Alasdair MacIntyre has argued, if one tradition can explain what another tradition cannot and can explain WHY the one tradition failed and the other did not, this is grounds to believe that the tradition with the wider explanatory power is truer. “Truer” is important since we will never have perfect knowledge, but there are traditions that account for that limitation as well.

A short book on the subject is “Tradition: Concept and Claim” by Joseph Pieper. He argues that tradition (and here he means sacred tradition) is ultimately true and authoritative because it originates from an utterance from God. Thus, the strange similarities between traditions in pagan cultures and Christian cultures can, he believes, find their roots in an original revelation. Of course, the pagan versions have been twisted and partially forgotten; nevertheless, there is common ground. As he puts it, “real unity among human beings has its roots in nothing else but the common possession of tradition in the strict sense–I mean, our sharing in common the sacred tradition that goes back to God’s words.”

sdf

Fix

The puzzled ones, the Americans, go through their lives

Buying what they are told to buy,

Pursuing their love affairs with the automobile,

Baseball and football, romance and beauty,

Enthusiastic as trained seals, going into debt, struggling —

True believers in liberty, and also security,

And of course sex — cheating on each other

For the most part only a little, mostly avoiding violence

Except at a vast blue distance, as between bombsight and earth,

Or on the violent screen, which they adore.

Those who are not Americans think Americans are happy

Because they are so filthy rich, but not so.

They are mostly puzzled and at a loss

As if someone pulled the floor out from under them,

They’d like to believe in God, or something, and they do try.

You can see it in their white faces at the supermarket and the gas station

— Not the immigrant faces, they know what they want,

Not the blacks, whose faces are hurt and proud —

The white faces, lipsticked, shaven, we do try

To keep smiling, for when we’re smiling, the whole world

Smiles with us, but we feel we’ve lost

That loving feeling. Clouds ride by above us,

Rivers flow, toilets work, traffic lights work, barring floods, fires

And earthquakes, houses and streets appear stable

So what is it, this moon-shaped blankness?

What the hell is it? America is perplexed.

We would fix it if we knew what was broken.

“Fix” by Alicia Suskin Ostriker, from No Heaven

Wessexman

It is as true as ever that democracy is not perfect on it own and needs to be balanced by aristocracy and monarchy as well as different layers of gov’t, the rights of community and intermediate associations and I would say some sort of established church or at least religious ethos. Not that we have democracy as such in general, we have mixed gov’ts, as all half-stable gov’ts but be, they are simply cloaked in a garb of democracy, particularly mass democracy, uber alles which helps to undermine the stability and balance of our gov’t, which are already quite utending to be more and more unbalanced what with their increasing centralisation, uniformity and such.

It is of course not true that democracy will give the necessary support and recognition for individuals to create a strong and healthy society. Democracy is simply one aspect of one aspect, ie the political, of society. A strong social and cultural tradition and institutions are necessary both to support the political sphere and the rest of society. To pin all your hopes on an atomistic idea of individuals coming together in mass democracy, even one that isn’t completely centralised, is absurd for anyone who recognises the depth of society and culture and their importance for the individual.

MMH

You write that “[s]uch a framework [e.g., religion] makes possible the idea of a common good. And a conception of a common good is what makes a community possible.” And, “Only where a particular tradition is embodied in a particular location (and where else can a

tradition be embodied?) is community possible.” I agree fully, but where does one find a shared conception of the common good? Where does one find “a particular tradition embodied in a particular location”? Front Porchers insist on geographical community, but today this seems pretty unrealistic for most of us, at least in my experience. Even within a particular church, such a shared conception is hard to find. Now, the idea of spiritual community, tradition, democracy of the dead, is something I find much more convincing for today. It’s a poor substitute for us embodied humans, but it’s better than nothing.

Bruce Smith

The principle reason for the restless mobility, consumerism, frenzied sexuality, substance abuse, therapy, and boredom is that we’ve lost the power to “sanction” both individually and collectively. By “sanction” I mean the ability, usually as a collective response, to stop the power of our own autonomy being stripped away from us and our lives being dominated by others with the “others” usually being in the form of institutions both private and public. Until we recognize that imposing coercion on others comes from our own human nature but we can oppose this by responding with coercion based on our own agreed ethos of the common good and good practice for implementing it we are not going to greatly improve this state of affairs.

Mark Perkins

Your article was an excellent take on the rootlessness of Western society–and our consequent lethargy and restlessness.

And Fukuyama, despite being very smart, is also monumentally obtuse–traits which are both shared by Victor Davis Hanson and all the other last-epoch liberal democracy believers.

Comments are closed.