Devon, PA. One of the paradoxes the Christian view of human life uncovers is the curious fact that private property is all but an essential condition for a flourishing human life, but the moment we conceive of our bodies or our selves as property, our undoing has begun.

Devon, PA. One of the paradoxes the Christian view of human life uncovers is the curious fact that private property is all but an essential condition for a flourishing human life, but the moment we conceive of our bodies or our selves as property, our undoing has begun.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, whose conclusions on the nature and role of property in life remain unsurpassed, notes that men tend to live best when they own that for which they are most responsible, and so the household flourishes, which leads to the community’s flourishing, which helps make possible the life of contemplation (of work and prayer) that is ordered, through grace, to Christian salvation. We just take better care of what we own. But why, then, do our children tend to become monsters–monstrous meritocrats like David Brooks’ “organization kids” or monstrous hedonists of anti-culture–when we treat them as property? And why, further, is the one sure way to make bad decisions leading to grotesque ways of life and the most socially and personally destructive pursuits–why, again, is the one sure way to destroy one’s body and to incinerate one’s soul to treat them as if they were every bit one’s own like a patch of land or a side of beef?

I know John Locke remains the philosopher of modernity most rightly reviled on FPR for his role in the disfigurement of our ideas of society, wealth, and property. Behind all these, of course, lies his inception of the individual as the political entity — an innovation in some ways more bold — certainly more devastating — than Descartes’ conception of the ego as the sole entity in knowledge. Descartes may have made “I” a troubling pronoun that, when fixated upon, drives the good natured to loneliness and the lonely to self-slaughter. But my undergraduates find Descartes’ meditations silly; they are more at home in the world than his philosophy allows. Locke made “my,” as in, “my body,” not simply a possessive but a possessive that we can now interpret only in the categories of sovereignty and ownership. My undergraduates, accordingly, cannot conceive of its having any other meaning — least of all, for instance, a mere means of distinguishing one thing from another much as we might, while driving with a loved one down the highway during congested traffic, point our finger violently into the distance while shouting, “No, the second right!” Such is the consequence of our existential enclosure laws.

This Memorial Day, we might ask whether the language of property rights is really condign to explain the sacrifice of one’s life for one’s country, whether such language does not, in fact, diminish the sociality of our everyday lives and the constitution of each of our lives as a gift from our parents, our ancestors, our communities and governments, and ultimately and most efficiently from God. We can scarcely breathe without realizing how little of ourselves belongs to ourselves, how there is nothing that is simply “me,” because there is nothing that is me that I have not received from another.

Other essays, including those most recent that have reflected on the theology and social doctrine of Pope Benedict XVI, have tried to address these questions at their most profound level, though the meditation on them of which I am most proud appeared here more than a year ago as Letter from a Traditional Conservative. In the letter to my father in Four Verse Letters, I reflect on the ideas and relation of art and nature, and in the fourth, concluding section of that poem, I offer the following meditation on ownership and culpability–one that has Locke always in the background.

For the reader encountering this section of the poem without having see the first three, it is worth my noting that the reference to Joseph de Maistre near the end picks up a discussion from the second part of the poem, where I describe Maistre’s conception of nature as, in brief, the morally indifferent realm of pure power — goodness, for him, must come by grace from outside nature, and so nature per se is simply the condition of what is, offering us no guidance as to what is right, what should be. But this is incidental to the meaning of the passage as a whole. The casual reader will note that I indulge a little anti-suburban imagery in the opening lines; I find them a bit cheap now, I confess, but that does not mean I find them inaccurate; I was then, and continue to be irritated, by the suggestion of such as Michael Novak that somehow the fulfillment of a society of flourishing private ownership could lead to the sprawling grids and enervating consumption cocoons of the modern American suburb.

Finally, I note that copies of my Four Verse Letters are still available for sale. Find out how to pick up your copy here.

Verse Letter to My Father IV

Those rare nights, Father, when we sit across

The table from each other eating our

Suburban dinners in a house of beige,

Within that quiet privacy of hours

We hear, like tumblers slipping in the locked

Back door, a TV drama’s children of

Divorce, their pierced and tattooed proclamations

They recognize no outside or above.

They’ve claimed their bodies as the cowboys claimed

The West: with clumsy rhetoric, barbed wire.

You stare down at your plate, without reply,

Biding the hours till you can retire.

I would be silent too. The ownership

Of houses, all that talk of men and castles,

Long ago slipped into the market place,

Decreed that feet and bowels were but vassals,

The merchandise of our unruly wills.

Your body’s yours, just as this poem is mine:

To make, destroy—a tenancy of will,

For every citizen and concubine.

Creations of a world we helped to make;

That stripped chicken bone on the gravied plate

Betrays us as the beneficiaries

Of terms that, without Terminus, now grate.

So this embarrassed quiet and the question:

Can we untangle casual wants and bodies

From the stretched net of private property?

Or has the gleam of television, shoddy

And obvious as it sometimes seems, made all

Things, real and false, true or imagined, turn

Monochrome, till appearances are all,

And all things can be ours, if we just learn

The necessary digital techniques?

With Wellesian aplomb, our journalists ask

If fiction can be passed off as pert fact.

But surgeons, salesmen have taken up the task,

Just like a mirror, of making fantasies

As actual as your own actual skin.

Which must be why some artists throw their shit

Or sperm upon a canvas; however thin

The charge, they want us—we who dine—to feel

The shock of the real. Such crude artifice

I’ve tried to stay from sundering this poem,

To offer sense, rather than ugliness.

But following Horace, I have had to note

Neatly the very monsters that I fear.

If they embarrass both of us, at least

They’re only words, not spectacles in clear

And gaudy color, road signs on a path

Of nature, warning of inglorious ends.

And that, in truth, is what our nature is:

The course from birth to death that we must wend

To be mere human beings; no set of laws

Gleaned watching wild dogs rutting in a wood,

But what we learn from living through our doing

In exodus from goods to final good.

Burke almost had it right. Just as this meter

Grew gradually out of native English stress;

Just as the cut of fabric and the stitch

Must match the body’s contours if a dress

Of worm-spun silk or suit of gabardine

Are to be worn with any elegance;

Hence to the rhythm of our lives we learn

The steps and missteps that become its dance.

Now, Father, at the sight of ownership,

Don’t wither in the silence shame induces.

Our oldest concepts have their applications

As well as modern and antique abuses.

I, like de Maistre’s boy, have grown up, discerned

Authority of a supernatural

Order shows much—but only to complete

The proper order in the human halls

We each pace leaving echoes in our wake.

And so we find that the grip of our pleasure

Need not choke everything it can, but may loose

The fist of art to fit the palm of nature.

5 comments

Jack Stewart

I liked Jas. Matthew Wilson’s “A Tenancy of Will” as well as Mr. Sabin’s excellent amending comment about work.

From where I sit, stand and work, it appears to me that American conservatives and American liberals (in general) do not see what they have in common. What they have in common is this: they subscribe to this claim: “It’s my _________, and I can do what I want with it.” They differ only in how they fill in the blank. As I see it, the Christian is not free to make this claim, no matter whether you fill in the blank with “real estate” or with “body,” with “horse” or with “daughter.

“This limitation applies equally to nations and civilizations. We are not free, eg., to pursue the “American way of life,” if in doing so we cannot avoid ruining the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico. Or, in the language of the BCP and the Bible, we are not free to follow the devices and desires of our own hearts and the works of our hands so much that we have no regard for the works of God.

John Gorentz

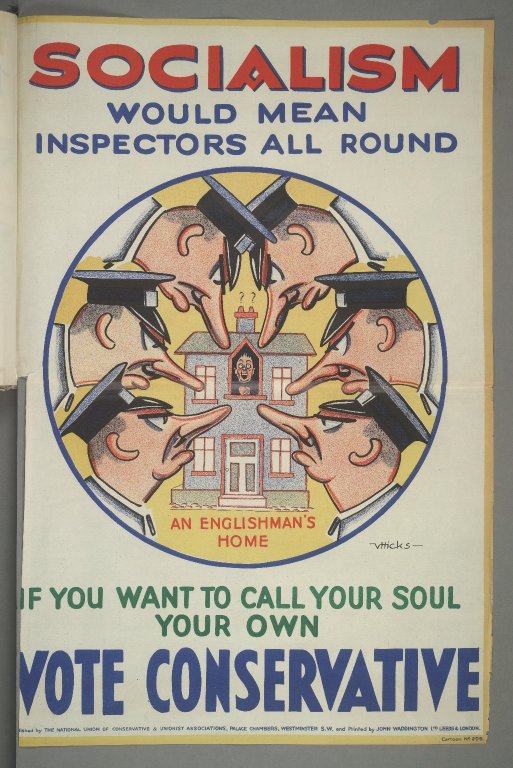

I like the poster, but after reading your article I can see that we need a better one — one that offers more choices.

D.W. Sabin

It is the work required of property ownership that is the chief virtue. Now, when property is considered some form of debt-financed right and work is deemed a pejorative, property is reduced to throw away commodity….something to be carried and flipped. An entire fleet of so-called “services” have emerged to allow one to hold property without the work required of it. Leisure is the new Property. We labor briefly for repose and distraction and stare in wonder that decadence would seem to be the strongest employment growth sector. No amount of property can fill the void one experiences when one cannot enjoy the clarifying effects of work.

It should be of no surprise that a people who have lost pleasure in work will soon see no value in property.

Comments are closed.