Baby-boomer nostalgia is particularly tiresome. Often combining a fetish for childhood television shows, lunchboxes, and toys with a self-righteous attachment to their role in America’s cultural liberation, boomers look back as though their generation stands apart. Generally dismissive of nostalgia as wasted energy, they have reasons to except themselves from the general rule. They changed—they improved–America. Their youth represents the dream life of golden myths—of simple times and comforting certainties—while their early adult-hood forced them to confront the ugly reality of racism, imperialism, gross materialism, political corruption, and a deeply rooted cultural hypocrisy. Their generational experience includes both comforting and idealized golden myths of the American dream and the heady excitement of cultural revolution. They yearn for both innocence and rebellion.

A variety of books by baby boomers about baby boomers indulge in this nostalgic narrative. One common characteristic of such books is to accept that there is such a thing as a baby boomer experience, and while this is a handy falsehood or sloppy generalization, I think it worth reflecting on the development and transmission of such a generational narrative that, in some measure, helps manufacture a constellation of memories for many people. No doubt, many individuals of a certain age fold their own remembered pasts into a generational narrative, creating a running montage as the backdrop to their real experiences.

The tendency to think in terms of generations, of generational experiences that define an age cohort, is a product of speed. During ages when change is glacial and when technology remains almost constant for decades or centuries, when social and economic conditions alter at a pace that requires historical analysis to detect—during such ages the experiences of life are amazingly consistent across generations. A man might very well assume that his father, his grandfather, and his grandson all participate in the same culture, the same economy, the same religious beliefs, the same constellation of experiences that shaped his identity. People separated by perhaps two hundred years share the same “relevant” knowledge or beliefs. They all belong, as it were, to the same civilizational generation. In some sense one might claim that these people are bound by historical memory and have no reason for nostalgia.

Much of the human story, however, includes people who live through very rapid change and who experience themselves occupying a distinct time or age. They understand that something significant enough has changed as to produce a before and after experience, leaving them aware that there is no going back. For a man born in the United States in 1920, for instance, his lifetime seems full of such transformations. A great depression, a world war, and a subsequent economic transformation (to say nothing of the attending changes in society, politics, and religion) certainly set his generation apart from his parents and his children. Things had changed dramatically and rapidly, and the austerity of his teenage years followed by the nationalistic regimentation of his twenties, gave his life, his beliefs, his fears and expectations, a shape that fit no previous or later American generation. He knew that he and his generation were different.

Consider how this man, in his late twenties and his thirties, raised his children. What experiences from his own youth prepared him to think about rearing the next generation? Perhaps he wanted to give his children a childhood that fate had prevented him from having, or perhaps he accepted that a new age of consumerism and prosperity required that he develop a new way of parenting to adjust to a new reality. Whatever choices he made in his new ranch home in the suburbs, he could not expect that his experiences provided a meaningful guide to what his sons and daughters faced during their formative years. He could not really draw on historical memory to guide him well in such unprecedented circumstances. This disjuncture between one’s childhood and the conditions in which one had to parent was shared by both this generation and the boomers—and perhaps by each generation since.

And yet, we may have more florid expressions of boomer nostalgia than previous generations because it is more pleasurable to remember suburban comfort than rural or urban austerity, to ponder Woodstock than Iwo Jima. But there is more to it—a greater desire by boomers to think and talk about themselves, and this is why their nostalgia is so tiresome.

The boomer way of remembering deserves a book, for a choice in memory—especially in group memory—reveals a great deal. But for now, I am interested in this contrast between historical memory and nostalgia and I want to venture some thoughts about the value or meaning of nostalgia. I have already suggested that the speed of change helps produce generational consciousness. I will add now that it also fosters a way of remembering in which we moderns accept the deadness of the past, of our own past.

Milan Kundera reflected, in his novella Slowness, on speed and forgetting. The narrator, describing the obsessed need of a motorcyclist for speed, reflected that “the man hunched over his motorcycle can focus only on the present instant of his flight; he is caught in a fragment of time cut off from both the past and the future; he is wrenched from the continuity of time; he is outside time; in other words, he is in a state of ecstasy; in this state he is unaware of his age, his wife, his children, his worries, and so he has no fear, because the source of fear is in the future, and a person freed of the future has nothing to fear.”

And so Kundera associates speed with forgetting and forgetting with both ecstasy and fearlessness. Intense focus on the immediate, blotting out all that is not in this existential moment, brings ecstasy. But the forgetting necessary for such ecstasy is not just of the world outside of the experienced bliss, it requires a degree of self-forgetting. A person who can escape the sadness of bitter memories or the melancholy of remembered delights that are forever gone can enter fully in “pure” experience. Necessarily we approach new limits when we think of “pure” experiences since some understanding of self, some development of personhood, is necessary to participate in experiences of the sort we so often want in those moments of out-of-time ecstasy. Nonetheless, Kundera is right, when he claims that “in existential mathematics….experience takes the form of two basic equations: the degree of slowness is directly proportional to the intensity of memory; the degree of speed is directly proportional to the intensity of forgetting.”

The purer the experience (the less we give form or structure to the moment) the less capable we are of remembering. So why do we moderns seem to want to provoke a chain of barely remembered existential moments? And to the degree that we embrace the peculiar and intense pleasures of speed and forgetting, what happens to our civilization? Is our nostalgia a yearning for something specific about our past that is lost or for the pleasures of slowness? Perhaps the fact of modern nostalgia tells us something about our souls, even if the specifics of our grasping memories are often pathetic.

For a Pragmatist like John Dewey, nostalgia may reflect a residual attachment to essences. He would have us embrace fully the relentless change of existence and thereby accept that ideas, beliefs, cultural forms, and almost all civilizational accretions are simply accommodations to specific environments—to be shed as soon as the environmental conditions make them obsolete. To yearn for ways of the past simply reflects a pathological desire to stop change. History, or the past which we remember, does not instruct us, it merely weighs us down with obsolete beliefs.

Dewey’s argument rests on a categorical rejection of essentialism in all its forms and, more particularly, certain long-held beliefs about human nature and human needs. (He could hardly be more radically hostile to history.) But what if the reality we experience involves relentless change while humans possess a deep need for continuity and some fixed ontological orientation? What if speed fractures our selves and leaves moderns experiencing a reality that contains almost no felt relationship with a past prior to our individual experience? We might come to act as though we are self-created, venerating our power to create and to change, but we end up being like Edmund Burke’s “flies of summer,” living without any meaningful connection to a reality we don’t experience directly—no meaningful sense of inheritance nor any obligation to pass something down. Our reality is contained in our experiences. Most of all, if we live in the “unfolding present,” to use Walter Lippmann’s phrase, we lose much of our capacity to apperceive a reality beyond or behind existence. In other words, to the degree that we use speed to forget, we gain primitive intensity at the expense of knowledge of our soul. Nostalgia might very well offer a glimpse into the occluded reality in which our experiences are but events.

George Santayana addressed a tendency in Americans to love the primitive or barbaric because of its sensate immediacy when he wrote an excellent essay on the poetry of Walt Whitman (“The Poetry of Barbarism”). Amazed at Whitman’s peculiar genius at noting, describing, and celebrating immediate, sensual experience, Santayana wrote: “For the barbarian is the man who regards his passions as their own excuse for being; who does not domesticate them either by understanding their cause or by conceiving their ideal goal. He is the man who does not know his derivations nor perceive his tendencies, but who merely feels and acts, valuing in his life its force and its filling, but being careless of its purpose and its form. His delight is in abundance and vehemence; his art, like his life, shows an exclusive respect for quantity and splendour of materials. His scorn for what is poorer and weaker than himself is only surpassed by his ignorance of what is higher.”

Perhaps one experiences barbaric ecstasy in Whitman’s poetry, but the author has lost contact with form and structure, and with any sense of an ideal. Cultural forgetting is the necessary condition for this ecstasy—the price we must pay for the intense gratification of immediate experiences is the loss of contact with ourselves, our essential being. Or, to put this in a broader framework that touches on the challenges of modern speed and civilizational memory, we might remember Santayana’s most famous and most misrepresented quotation, found in volume 1 of The Life of Reason. “Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement: and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In the first stage of life the mind is frivolous and easily distracted, it misses progress by failing in consecutiveness and persistence. This is the condition of children and barbarians, in which instinct has learned nothing from experience.”

When he wrote that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” Santayana had no thought of academic history, of ever more intricate explorations into the details available by existing resources about the past. Neither did he mean to suggest that we avoid mistakes by studying the past and learning lessons from previous failures. Rather remembering the past is about a way of living, an incorporation of the civilization that gave one life, direction, shape, and even purpose. As historical creatures we are part of something much greater than a moment or even a generation. But as barbaric creatures (defined by those who have lost historical consciousness) we live in perpetual infancy, making each moment alive with spontaneous intensity, but impotent to create our better selves, to progress toward standards, or to find ourselves in meaningful relationship with purposes greater than those we give to our own niggardly span of days.

Speed has given us ecstasy, forgetfulness and nostalgia. Nostalgia is about extinction. Historical memory is about continuity. Nostalgia is about the dead past. Historical memory is about the living past. For over one hundred years we have become progressively nostalgic, our past ossified and dry, littered with debris of lifestyles and folkways, now obsolete. Our historical horizons shrinking, few of us can hope to pass along meaningful and living traditions to our children whose fate it is to grow up in a world dramatically different from that of our youth. Nostalgia is, therefore, an index of alienation, communal decrepitude, and, at high levels, cultural patricide. Hence, nostalgia is evidence that our civilization is no longer a partnership in all good things.

In the end, however, nostalgia points us to needs we cannot satisfy. Nostalgia is a very debased form of yearning for home and therefore a reminder that we are homeless. As a sign of alienation, it not only supplies us with hints to the danger of our modern obsession with change and forgetting, but it also is part of the human condition that reminds us that we yearn for something unchanging even as we live in the midst of constant change.

12 comments

wufnik

As a boomer who looks at the wreckage left by my generation, I’m not unsympathetic to your approach, but I need to consider it in more detail. We’re a complicated bunch, us boomers. I admire your efforts to try to bring some order to a complex problem.

And here’s a good, and relevant, quote, from Gandhi!

“There is more to life than increasing its speed.”

P.D.H.

Ted,

You deal with some very profound questions here. This is quite excellent.

Best,

PDH

Ian Fly-Slayer

“For a Pragmatist like John Dewey, nostalgia may reflect a residual attachment to essences. He would have us embrace fully the relentless change of existence and thereby accept that ideas, beliefs, cultural forms, and almost all civilizational accretions are simply accommodations to specific environments—to be shed as soon as the environmental conditions make them obsolete. To yearn for ways of the past simply reflects a pathological desire to stop change. History, or the past which we remember, does not instruct us, it merely weighs us down with obsolete beliefs.”

As well as being inhumane, it is interesting that Dewey also seems straightforwardly self-contradictory here. To say man has no essence and must adapt to his circumstances is really to (surreptitiously) argue that man does have an essence, which is continual adaptation.

Since something can’t have and not have an essence, Dewey should have either taken up the task of defining man’s essence, and argued why it is constant and ruthless adaptation, or he should have remained consistent to his premise and admitted that man having no essence means he may have need of ossification as much as progress (something his more clear-minded mentor, William James, would have certainly admitted).

John Gorentz

As a baby boomer, I find the version of baby boomer nostalgia promulgated by the celebrity-media-news complex to be revolting. But I find just about everything about the mindset of the American celebrity-news-entertainment media to be revolting. I do not want my own thinking to be further contaminated by their ideology, narrow-mindedness, ignorance, and stereotypes, which is why I quit watching American news, TV and movies many years ago. When I bother to think about them I spit on them.

But this morning, for some reason, I found myself explaining the John Deere “B” tractor to some older college students; telling them how for a generation of people who grew up in rural America the sound of those tractors represents the sound of a farm. There’s some baby-boomer nostalgia there — at least for older boomers. One of the young men was interested, saying he was going to ask his grandfather about it when he visits him on his Tennessee farm in a few days.

A few minutes ago I finished watching the movie Бабуся, thinking as I watched it that a lot of Front Porchers would probably like it, too. (I downloaded it here. There are English subtitles.)

Some of the scenes have nostalgia value for me, even though they take place in a country different from mine, and absolutely different from the America that I’ve seen portrayed by the American media for as long as I can remember. But there is no point in my trying to explain it, because there are probably not one in a hundred thousand Americans who would know anything of the America it reminds me of. (I watch a lot of Russian movies partly for the nostalgia value, but have not succeeded in explaining to anyone why that is, except perhaps my wife understands a bit of it, too. She watches a lot of these movies with me.)

But I think a lot of Front Porchers would like this one even if it wouldn’t have the same nostalgia value for them. (BTW, the acting of the lead character is probably the weakest part. But the movie is still good.)

Ted V. McAllister

I suppose it was inevitable that an essay in which I begin with some brief thoughts about boomer nostalgia would provoke many responses, pro and con, about baby boomers. But the opening discussion is an appetizer, not the main course. If read in the context of the my later discussion about speed and the altered way of remembering that comes with both rapid change and an accelerated pace of life, my comments about boomers (of which I am one) has a more ambiguous quality.

I sought to raise more questions than I answered in this essay—to open a set of questions about the meaning of nostalgia. Unlike some who have responded, I do not think that every generation has the same way of remembering. Because memory is produced in the context of a constellation of circumstances, the differences between the way people of an age remember reveals something about who they are (or were). In other words, describing and explaining diverse ways of remembering is an important part of the historian’s task of telling history.

Moreover, the empirical evidence that people in different times have different relationships with time, with memory, with ancestors and descendents, is so overwhelming that I have trouble believing anyone who has studied the historical evidence can deny this very rudimentary claim. It may be that the sense that people have that our contemporary way of remembering (of thinking in terms of generations, of becoming nostalgic as a cohort ages, etc.) is natural and universal suggests something about the provincialism of our own time and culture.

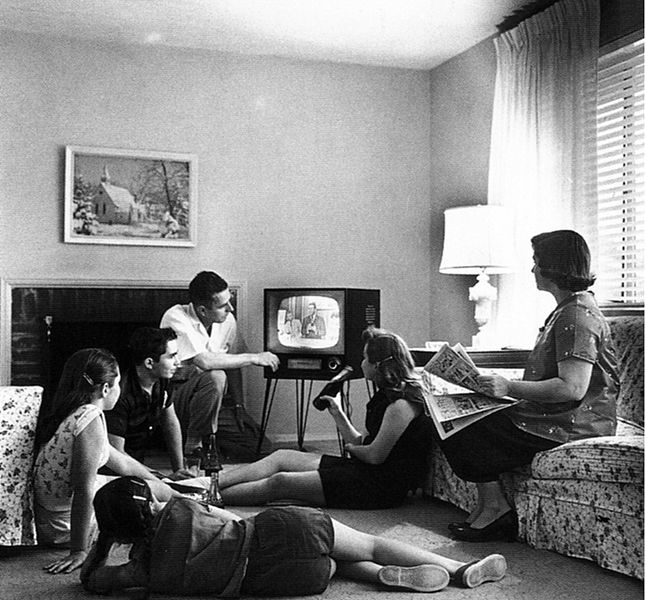

I won’t here try to draw out the empirical evidence, but to note one fact about boomer nostalgia that is important to their memory (This is not exclusive to the boomers, but it is certainly important to them). To get the clarity necessary, let me offer this in the form of rather different ages. Boomers, who grew up with what Daniel Boorstin aptly called “the graphic revolution,” are saturated with images that are shared nationally or internationally. Not only did they participate in a consumer culture that provided them with a common but national experience, but now as they see pictures of Woodstock, of civil rights protests, of Vietnam, or Beaver Cleaver, they often accept all of these as “their” experiences, no matter how distant they were from the events. Clearly a similar generational memory was impossible for those born in the middle of the 18th century. This obvious difference is hardly the only one. But the larger point is that the particulars that foster, shape, and constrain memory for any group of people is much more important than an easy generalization about humankind as such.

As to Grammar’s critique, we can certainly agree that we see things differently. Beyond that, I find so many confusions in these comments as to require more space than I should take here to clarify. I will, instead, only note that I offer no “paradigm” and I do not harken back to a slower time. Insofar as there is an underlying claim about humans, it would be as follows. 1. Humans are alienated or homeless creatures. 2. The degree to which humans feel or experience this alienation, AND THE MANNER THEY EXPERIENCE IT, is far from constant. 3. While change is a human constant, its nature and pace is not—and it doesn’t not necessary have a clear trajectory. 4. In modern times, speed has allowed humans to experience life as given—to have moments when we can forget that we are a part of history. 5. When speed creates such temporary forgetting, it also tends to produce nostalgia, and this nostalgia emphasizes that the recent past is largely dead as a form of instruction for the unfolding present. 6. Therefore, nostalgia, in this context of speed, has at least (perhaps more) one important quality—it reminds us of our existential condition as alienated cultures.

No paradigm. No harkening for any given time.

Thomas McCullough

I was 18 in 1969 and so am of that generation. I find myself treasuring fondly memories that are at the same time more universal and more personal, first love, first own home (apartment, rather) when I had, to a modest extent, my own money in my own pocket; in sum, that first freedom. As one does, I probably rose-tint it some. It is, however, my specific version of stuff experienced in every generation. I don’t have a particular nostalgia for the ’60s as such, its bungling sincerities, its astonishing bad taste. I think people sometimes attach their memories of the fluorescence of youth to the ephemeral idiosyncrasies of a particular time.

That said, I must concede that the sixties did have an identity tied up mostly with the Vietnam War and with drugs. However, as has been already observed, I find the most interesting thing about the sixties is the fairly potent antagonism it gets from so many people born later. The traits that seem to draw the downright malevolent reactions are its (frequently foolish) optimism and Faith.

Grammar

The irony of this piece is profound. The author’s attempt to critize nostalgia belies its many manifestations within this article. The assumption is that nostalgia is a new phenomenom, a product of an industrialized modern world. This paradigm, however, fails to acknowledge the fact that nostalgia is not a novel way for humans to make sense of the past. Every generation has employed nostalgia and the failure to recognize this fact, as a demonstration of contitinuity rather than change, only further illustrates the nostalgia employed in this article. It harkens back to a slower time when people really understood history and historical memory and were never subject to the comforts of remembering the best and forgeting the rest. I’m not sure when this time was, but it was sometime before the speed of the modern world destroyed the integrity of historical memory in favor of that great modern paradigm, nostalgia. In attempting to expose the baby boomers the author has exposed himself.

Cecelia

Well I am a boomer and frankly – I ain’t met any of these nostalgia crazy boomers nor do boomers of my acquaintance talk endlessly about themselves and their times. But maybe I just know a weird group of people.

I find the antagonism towards boomers by the generations that follow us to be intriguing – blogs nowadays are full of screeds about those wretched boomers – especially about our nervy desire to actually collect that social security.

But in the interest of some facts here – as someone who has a very enterprising young one in the family who is selling nostalgic items online and makes a salary that exceeds what what her Dad and I made the year she was born ( making me wonder why we are spending gobs of money on her tuition when it seems hanging out at garage sales with an eye towards what to buy can earn one a fine living)- the market for nostalgia is not us no good boomers but rather the 20-30 year old group. Boomers are getting rid of their stuff as they downsize – and discovering that there isn’t much of a market for those Howdie Doody lunchboxes. You wanna make money in the nostalgia market nowadays – Strawberry Shortcake, He Man and My Little Pony is the way to go.

Tim R

I’m too young to be nostalgic about anything myself, but it seems to me a yearning for “the good old days” is unique neither to this time or place, or the Boomer generation (though, as you point out, they make a more tiresome show of it).

As to the state of the modern, I’d suggest the change isn’t so much a philosophical one as it is a conditional one. Our species is undergoing what is likely the greatest change in its history since the invention of written language, and we are left not knowing how to react. The centuries of tradition handed down to us only partially address the world we see today, and we have not yet developed new philosophies to deal with them; it’s as if we’re stuck in limbo, and postmodern “philosophers” throw up their hands in defeat under the illusion that if the old ways don’t work, nothing else will either.

I suspect we are not so much “moderns” as we are “transitionals”–we are still in the throes of technological revolution, and it remains to be seen how we will come out of it.

Saint Louis

What bothers me the most about Boomer nostalgia is not so much how vocal they are about it, but their almost complete lack of introspection. They constantly think and talk about themselves, yet have almost no self-awareness. They long for a dead past, yet they’re too obtuse to realize it was their own generation who murdered and buried it. The social upheavals for which they are largely responsible are the very reason childhood is much less innocent today than it was in 1960.

Wesley Morris

Nostalgia is such big business now for two reasons: The boomers are the biggest living generation; the boomers are graying. And people are more prone to indulge themselves with certain things if more people like them do it as well (in this case, indulge with nostalgia). If the boomer generation wasn’t nearly as big as it is, we would not be seeing this deluge of boomer nostalgia. The older people get, the more nostalgic they become–even people who spent their whole lives not being particularly nostalgic will start looking to their past more and more as mortality starts becoming more and more familiar. The boomers are no different. It’s just that their numbers are greater, generationally speaking, so it may seem like they are being more vocal about their past. Personally, I see nothing wrong with looking back, as long as you keep your awareness of the here and now with a glance toward the future.

Bruce Smith

Fear of death makes us search for immortality and for some this induces greed.

Comments are closed.