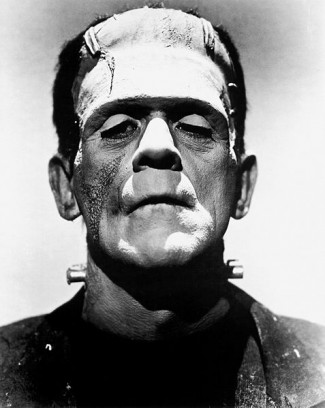

“I was, besides, endued with a figure hideously deformed and loathsome; I was not even of the same nature as man.” So says Frankenstein’s creature. After being animated, the beast fled from the laboratory and embarked on a painful journey of self discovery. The beast sees his own reflection in a pool of water, but, unlike Narcissus, he is disgusted. He sees a cottage of rustics and watches their happy life together, prompting him to wonder at his own nature. “Was I, then, a monster, a blot upon the earth, from which all men fled and whom all men disowned?”

Over the course of Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus Mary Shelley unfolds the answer to that question, and it is a horrid and tragic yes. Frankenstein’s creation is indeed a monster, and his monstrosity constitutes a sort of tragic flaw, damning him to perpetual enmity with mankind. His intelligence and strength are warped and redirected towards malicious ends, and he himself moves ineluctably towards his own doom. What, however, is the nature of his monstrosity?

Aristotle provides us with a valuable definition of the monstrous when he writes in his Physics: “If then in art there are cases in which what is rightly produced serves a purpose, and if where mistakes occur there was a purpose in what was attempted, only it was not attained, so must it be also in natural products, and monstrosities will be failures in the purposive effort.” Aristotle’s monster, teras in Greek, is an aberration. It is a product of natural processes that is itself unnatural because chance has diverted the course of its generation. He gives the example of an ox calf born with the face of a man, a hideous thought. Aristotle’s monsters are often what we would call mutants in this day and age, deviations from the course of nature that fail to attain their purpose and intended form.

Shelley and Aristotle both wrestled with this notion of the monstrous, but it seems that the notion has gone out of vogue. That is strange, because if monstrosity ought to be understood as aberration from the design of nature, then we are beset with monstrosity on all sides in this twenty-first century. Witness our sprawling cities, filled with moral and ecological pollution. If we have ceased to perceive monstrosity, perhaps it is because we have become accustomed to it. In order to reacquaint ourselves with the conceptual category of monstrosity, and see how it may apply to modern megalopolises, perhaps we ought to return Shelley’s work and study her portrayal of the monster.

When we consider that Frankenstein’s monster is a conglomeration of inanimate tissue that is living even though it ought to be mouldering in the grave, we realize that this creature is an Aristotelian monster. Dead tissue has been diverted from its course. However, unlike the malformed births that Aristotle considered, Frankenstein’s monster is not the result of freak happenstance. Instead, the monster is the result of one man’s disordered will.

Frankenstein himself, reflecting on the two years he spent working on the monster, tells the reader that “No one can conceive the variety of feelings which bore me onwards, like a hurricane, in the first enthusiasm of success. Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world.” Here Shelley shows us the rampaging spirit of the Enlightenment, transgressing all bounds and expanding outward, driven by men gone mad with their own imagined powers. Frankenstein is borne along by winds of passion that, with the force of a hurricane, compel him to work on his project night and day. This monomania leads him to ignore his familial obligations and forget simple pleasures that he once enjoyed. It is his disordered desires that lead him to interrupt the course of nature and produce the monster. His feverish quest comes to fruition on the night that he animates the body, and realizes instantly that he has created a monster.

“How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.”

Here we see the dominant feature of the monster: ugliness. There is an irony here; because Frankenstein sought to create a beautiful creature, he chose “teeth of a pearly whiteness” and other exquisite elements. However, when he combined them the result was repulsive. The individual accidents participated in a monstrous substance, and thus could never unify into an excellent whole. Indeed, there is no ideal form that the beast is meant to attain. Indeed, if beauty is the splendor of truth, then perhaps ugliness is the penumbra of its absence.

The monster is, for one thing, too large. Frankenstein identifies his creature one night during a lightning storm when “its gigantic stature, and the deformity of its aspect more hideous than belongs to humanity, instantly informed me that it was the wretch, the filthy daemon, to whom I had given life.” The beast, which was created by transgressing the natural limits of life and death, violates the limits imposed by the human scale. The enormity of the monster, like a work of brutalist architecture, causes revulsion when Frankenstein considers him.

This hideous appearance, and the visceral reaction humans feel when confronted with it, helps to drive much of the plot forward. When the monster seeks to forge a relationship with a family of cottagers, they reject it out of aesthetic disgust. This, and similar encounters, lead the monster to determine that it can never live in peace with mankind. A modern author would doubtless condemn the peasants’ impulse to judge a soft-hearted being by its physical appearance, but Shelley does not. The ugliness of the beast reflects a deeper truth about it, the fact that he is fundamentally and essentially monstrous. Because he fills no niche in the proper order of the nature, he must always exist in conflict with mankind.

Frankenstein’s monster is the result of diverting the natural processes of birth, growth, death, and decay. These natural cycles are not the only process towards an end that Aristotle considered, however. Aristotle also believed that the city, or polis, had an intended end. He wrote in Politics that the city “contains in itself, if I may so speak, the end and perfection of government: first, founded that we might live, but continued that we may live happily.” If men with disordered passions diverted the city from this end, they would create a monster that resembled a city. To boldly coin a neologism, it would be a terapolis, a monstrous city. This is not, however, a merely theoretical exercise. Over the last two hundred years, such monstrous cities have indeed sprung up across the globe.

Frankenstein’s disordered passions were not dissimilar from those of the early English industrialists that Shelley and her Romantic cohort despised. Frankenstein sought to use the scientific knowledge amassed in the Enlightenment burst through natural limits and satisfy his own macabre curiosity. The tycoons of Dickensian England satisfied an even baser impulse, they sought to amass vast fortunes by directing the scientific advances of the Enlightenment towards mechanized production. In their avarice they began to construct terapolises that drew displaced rural people into enormous slums. The same process is currently underway in central China, as enormous manufacturing centers erupt from the rice paddies.

This process of urbanization creates cities that do not aim at the good life. The end of these cities is to feed grist into the mill of industrialism, allowing a handful of men to amass enormous fortunes with no reference to limits. Aristotle condemned this acquisitiveness in Politics, contrasting it with economy, which seeks only to provide for the natural needs of a household. He wrote that: “Thus, in the art of acquiring riches there are no limits, for the object of that is money and possessions; but economy has a boundary.”

If these terapolises are indeed monsters like Frankenstein’s hideous creation, we should expect them to bear the same ugliness as the monster in Shelley’s novel. They do. Consider the architecture of Shanghai. The city contains ancient Chinese buildings, with beautiful gardens where visitors can stroll along winding paths and gaze on perfectly manicured trees and ponds. Shanghai also holds the Bund, a string of gorgeous Art Deco riverfront buildings constructed during the Jazz Age by foreign banks and trading houses. Along with these treasures, Shanghai is home to a profusion of modern Chinese buildings, skyscrapers of steel and glass that are illuminated at night with a brilliant and shifting kaleidoscope of lights. Like the lustrous black hair and pearly white teeth of Frankenstein, all these architectural styles have a beauty of their own. However, thrown together in the sprawling jumble of the twenty-first century mega-city and mixed with blocks of boxy and insipid apartment buildings, they add up to form a monster. Viewed from the top of the Pearl Tower, an impressive structure in its own right, the city is a teeming disarray of structures overlaid with an oppressive layer of smog. There is no unity, no clearly visible purpose. But behind the aesthetic chaos lurks the true (dis)organizing principle of the city: the quest for lucre.

All over the world we see cities that, like Frankenstein’s monster, are simply too large. Flying in or out of these terapolises can engender feelings of revulsion when elevation allows us to glimpse the horrific scale of urban sprawl. Walking down a busy street can call up feelings of claustrophobia and panic when we feel the press of human masses forced to live cheek to jowl, even if their cheeks and jowls are pressed together in stylish loft apartments.

Shelley’s novel ends in tragedy. The creator and creature meet for the final time, and the monster murders Frankenstein. The terapolis might follow the same course, and slowly choke from our species that which makes us most human, our love for God and our neighbors. These corrosive effects need not come to pass. There is still time to redirect the monstrous development of these cities, and point them once more towards their true end, the good life.

10 comments

Jon Cook

First, I really liked this piece, so I part with Jordan on that sentiment. It is well written and thoughtful. I also think the author would agree with Jordan that not all cities are “terapolies”, as they originally write that “[o]ver the last two hundred years, such monstrous cities have indeed sprung up across the globe,” so they are not condemning the idea of the city. However, I do think the author elevates the terapolis from a symptom to the level of almost a cause (the “end of these cities is to feed grist into the mill of industrialism, allowing a handful of men to amass enormous fortunes”), which is a mistake.

The question I would ask Porchers, who by far are pro-life and pro-creation (or should I say pro-procreation?) is: where would you have all the people live? The original command is “be fruitful and multiply” and “fill the earth,” and yet it almost sounds here like this is being condemned. Of course mega-cities have sprung up in the last two hundred years, because the world population has as well. What would you have us do?

dave walsh

Well, Vancouver is a lot smaller than Shanghai, I believe. It’s useful to talk about an upper limit, don’t you think? One of the subjects that Professor Mitchell often brings up is scale. The slant of my own thinking is such that when I read this “The individual accidents participated in a monstrous substance, and thus could never unify into an excellent whole.” what comes to mind is designing for cars instead of people. The differences between a parking lot and a plaza.

More, walking and cycling and I suppose I can throw in when on horseback my sense of limit and scale is different than what I perceive when I drive a car. I grew up fetishing cars and that’s never really gone away but whoa, they skew my perception of a reasonable scale.

Two more things. My criticism of the piece is that I don’t think the very, very rich are in any way tied to nor are they dependent upon people living in a particular place. I think it’s gotten to be more abstract, the extraction of capital. Or not abstract, intangible, maybe. Shoot. That’s not it. Back in English class again. What a nightmare.

Lastly, mentioning Shanghai, what’s going on in a place like China seems horrific to me. Webb is the one who’s sort of addressed it in the past on this site, if I remember. Not the forced urbanization, but the mass dislocation. That’s a whole different animal from the sorts of changes going on in a few urban centers in North America. There are some very large cities in this world, and it seems at some size, however many millions, comprehension becomes impossible which means to me that the administration necessarily becomes coarse. And I’d say at that point we lose the facility to treat each other humanely. That’s an error.

Jordan Smith

@robert m. peters: One notes that God chose to place man in the Garden and not in a city. One notes that there is a negative aura over Nimrod, and he built a city; and one is reminded that the Tower of Babel was an urban project.

This is true. But if you spend any time reading your Bible, you will also note God’s response to the City. While it starts out as man’s symbol of rebellion toward God, instead of choosing to curse it, God chooses to redeem it. (It’s funny how humans hate and curse and God chooses to love and redeem.) The imagery of heaven moves from a Garden to a City, culminating in the vision of the New Jerusalem in Revelation.

I really find the kind of blind hatred towards cities to be bizarre. I love cities even though I have made the choice to live in the country. I grew up in Vancouver, which has done a number of things to make urbanism extremely attractive. Vancouver is a beautiful city. Much of its success lies in density, density that has been made necessary by the fact that much of the available land for expansion has been protected by the Agricultural Land Reserve, an amazing bit of foresight and legislation put in place back in the 50’s and 60’s.

However, our provincial government is in the process of dismantling the Agricultural Land Reserve to facilitate more suburban sprawl! Unbelievably stupid. Suburbia is the enemy, not the city. It is auto-dependent and chews up valuable farmland. The healthy city of significant density may be the key to saving farmland and securing our food supply, and getting people out of cars and onto bicycles and into transit.

But instead of attacking sprawl which perpetuates Motordom and is eating up farmland, FPR attacks urbanization, and the beauty of diverse, healthy cities with community gardens, efficient transit, and cycle tracks. The city is the millennial’s inheritance, and they realize and accept that they must get by with less. They are not buying cars, and choosing to live in close communities of interdependence. Oh the horror!

I’m all for protecting the Agrarian tradition and small farms, but I’m also looking at the transformation that is going on in our urban centers. That should be something the folks here should be supporting.

Kenneth Cote

People are monsters, not their creations. What is Frankenstein’s monster but hubris made real? What is a city but a million stirring souls? I read somewhere that the slaughtering of horses may become legal again, and certain farmers in New Mexico are raring to sell their meat to China. Yes, even the country has monsters. As Rebecca Nurse says in Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible,” “Let us rather blame ourselves….” If you want something beautiful, make it.

Just A Undergrad

“The end of these cities is to feed grist into the mill of industrialism, allowing a handful of men to amass enormous fortunes with no reference to limits. Aristotle condemned this acquisitiveness in Politics . . .” Marx and Aristotle have never gotten on so well before!

robert m. peters

Marx was a secularized Calvinist who believed that societies were predestined to evolve into a stateless state of communism, with capitalism, with all of its baggage, being a necessary phase in that inexorable march. He, in fact, welcomed capitalism; for without it the next step could not be made. Marx was a 19th century positivist who believed in the progressive march of history. In such a context, Aristotle and Marx were not close at all.

The two evils of the false dychotomy of socialism (Marx as he was in the 19th century) and the emerging corporate manifestation of capitalism was fully understood by the Southern theologians Benjamin Palmer, John Girardeaux, and R. L. Dabney. They were the antecedents to the Vanderbilt Agrarians who outline this false dichotomy in their introduction to “I’ll Take My Stand” and in the sequel “Who Owns America” to which some of them among others contribute. Of particular interest is Allen Tates article in the latter about corporatism being a stalking horse for socialism.

Just A Undergrad

Your cool!

robert m. peters

Mr. Reidy has chosen to focus on the modern city, which unlike classical Athens, republican Rome or ancient Jerusalem were communal expressions of their respective agrarian hinterland. Rome as perhaps the best example of the three lost the objective correlative to its hinterland as Roman power spread and as Rome eventually became the capital of an empire and not of a republic, having become an imperial city long before the empire was actually acknowledge.

One hallmark of the monstrous is the artificial. Modern Southern cities, for example – Houston, Dallas, Atlanta, Charlotte -are artificial monsters. They have been brought into being by the infusion of alien capital, itself a fiat, and have little in common with their immediate hinterlands.

Another hallmark of the monstrous is closely related to the artificial: the abstract. Modern/post-modern/and beyond-post-modern Western societies are essentially the expressions of two Enlightenment abstractions: the Hobbesian state which is an abstract corporation with a monopoly on coercion, with the ability to define the limits of its own power and with the locomotive of a powerful will, be it that of a dictator, that of an oligarchy or that of majority democracy and its counterpart the would-be Promethean self, actually in the West counting Europe and the United States about 700 million would-be Promethean selves outfitted with the equally abstract rights of Locke, or the rights of man or human rights. In actuality, these would-be Promethean selves are estranged, shrivel and alienated selves whether they are the emerging artificial monster known as Miley Cyrus or an addict dying in the gutter of Detroit. The Frankenstein Monster is indeed the harbinger of the products of the Enlightenment. He has his antecedents in the biblical Cane and in Beowulf’s Grendel, bereft of fellowship, precisely what our teeming cities offer, not solitude but loneliness, an artificial fellowship sought out in the social media.

It is not a coincidence that books and films portray, yea, extol the vampire and the zombie: isolated, estranged, shriveled, and parasitic selves, somewhere between life and death, because that is precisely where we are as an anti-culture: abortion, euthanasia, sex without birth, drugs, a focus on deadening materialism, all hallmarks of the urban life, the poison of which, however, spills into what was once the rural and the agrarian. Therein is the difference between republican Rome and imperial Rome: republican Rome existed and depended on the vibrant agrarian realities of its hinterland. Imperial Rome, gaining its power from conquered territories and no longer dependent on its hinterland for virtues, for soldiers or for food, for this is what a healthy hinterland gives a healthy town, fed its decadence back into its hinterland and over time destroyed it.

One notes that God chose to place man in the Garden and not in a city. One notes that there is a negative aura over Nimrod, and he built a city; and one is reminded that the Tower of Babel was an urban project.

So, Mr. Reidy, you are onto something!

Earth Pig

The argument posited in the article is intelligent, thought-provoking, and down-right subversive. However, I believe that this argument hinges mainly on the perspective of the beholder. A city does not stand, to a modern man, as an abomination, but rather as a monument to human achievement. That same city, when observed by Shelley’s cottage rustic, may in fact constitute a monstrosity. The difference is in perspective. Man has a general fear of the unknown, the unexplained, that which is beyond his understanding. Is a bird’s nest a monstrosity? A beaver’s dam? Surely not. Why then should the evolution of human habitation be viewed as such? Frankenstein’s monster is a horror because it is a man-made freak, defying nature. Man could not comprehend the monster, could not coexist with it. However, a city can hardly be regarded as categorically similar. I understand how a city could be representative of man overturning nature in an attempt to satiate his appetite for wealth. But, I do not think that an argument reliant on comparing a city as an affront to nature, simply because it did not exist in nature before its creation, is sufficient to make the types of categorical claims made in this article. More of a connection needs to be made to the ultimate consequence of cities as a detriment to nature before I would feel wholly satisfied. If a city is so unnatural and is forever in conflict with nature, what is the outcome?

Jordan Smith

With the exception of Peters, FPR has been circling the drain for some time, but this pap might just be the dumbest article ever posted here. I wouldn’t even know where to begin.

Comments are closed.