[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

Caroline Fraser’s wonderful Prairie Fires is many things. Primarily it’s a biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of the justly famous Little House books, and her daughter Rose Wilder Lane. But it’s also an impressionistic study of several key moments in the history of the United States, from the 1870s through the 1940s. And it includes multiple extended observations regarding agricultural economics, environmental science, women’s issues in pre-WWII America, free-lance writing and publishing during and after the “yellow journalism” era, and most of all, thoughtful considerations of the intellectual milieus that gave rise to political perspectives ranging from the populism of the People’s Party to the proto-libertarianism of critics of the New Deal. It does all of those things, and more, very, very well. The result is a terrific book, one that any thoughtful reader can learn from.

The primary cause of the book’s success, it must be said, isn’t Fraser’s writing, research, and analysis, good as they are. (I think she sometimes leans too heavily on or reaches too far for psychological explanations, but only sometimes; usually her reasoning about the motives and mental states of the two complicated women she writes about is both careful and well-supported.) No, the real source of the brilliance of this book is the fact that Wilder and her daughter were compulsive diary-keepers, notebook recorders, and letter-writers (and letter-keepers!). The fact that Wilder’s fictionalized recreation of her pioneer childhood resulted in not only one of the great classics of children’s literature, but was a major contributor to late 20th-century America’s romanticizing of its late 19th-century history is, of course, the cause of the enormous amount of research, recovery, and preservation that has attended the life of these long-departed people. But if they were not the sort of people who wrote almost everything down in the first place, all that work–including Fraser’s fine biography–wouldn’t have had so much raw material to work with. They were, no doubt about it, two rather amazing individuals; of that there can be no doubt.

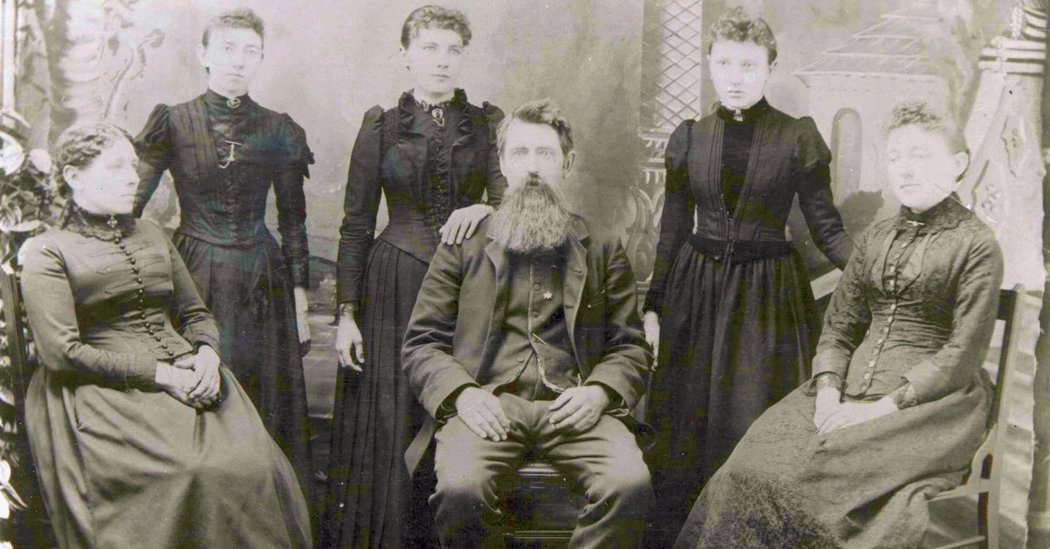

Truth be told, I also strongly doubt that, going off the detailed and fascinating portraits of them that Fraser provides, they were the sort of individuals I would have enjoyed spending time time with, or that would have enjoyed spending time with me. Wilder was a defensive and temperamental person, frequently suspicious, judgmental, and narrow-minded; as for her admittedly brilliant daughter, the kindest thing that can probably be said about Lane, what with her flirtations with fascism, her trail of betrayed friendships, and her self-aggrandizing paranoia, was that she was mentally troubled soul. (By contrast, Laura’s husband of 64 years, Almanzo, seems to have had a quiet equanimity and good humor which allowed him to get along with and see the best side of just about anyone.) But you don’t have to like an artist, or imagine being liked by them, to be captivated by the art they create. And over a long period of time, Wilder and Lane worked in tandem–sometimes willingly, sometimes not, sometimes with the mother taking the lead, and sometimes the daughter–to create out of Laura’s memories a beautiful work of art, a myth of the pioneering and the settling of the recently conquered Great Plains, which has delighted and influenced millions of people. I was one of them; I read all of the Little House books as a child (and no, I don’t remember being put off by having to follow the story of a female protagonist), and I read many of them, multiple times, to our four daughters.

So what, then, does this book add to what we take from the Little House myth? Fraser suggests that seeing clearly the cycle of deprivation, courage, failure, and resourcefulness that lay behind Wilder’s stories, and appreciating the emotionally taxing labor which characterized Wilder’s re-telling of those stories, as well as Lane’s editorial engagement with them, presents us with a deeply American tale: a will to re-invent oneself, but at the same time to create in and through that re-invention a meaningful continuity with the past. In the same way that Laura’s stories–by preserving her father’s struggles and songs, his love for his children and his abiding optimism–in essence “saved” her father from the desperate and difficult legacy he left his posterity, so do we all seek to create out of the memory of each individual life a means to preserve that which we wish to be, and maybe really do feel to be, true about those lives. But perhaps that’s not so much American as simply human.

More specifically American, I think, is the way Wilder’s whole story conveys the confusion and ambivalence which America’s transformation from a decentralized agrarian society to a centralized industrial one brought into the lives of the poor, white settlers who followed false promises of plenty during the late 19th century to Minnesota, Iowa, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas, and attempted, almost always without success, to homestead the Great Plains into productive single-family farms. No serious study of my own state of Kansas should elide that environmental and economic reality; Fraser’s work reveals, through Wilder’s and Lane’s personal reflections and travels, how that reality transformed those on the Plains, engendering both a romance of hard-won triumph and, much more frequently, a barely sublimated sense of shame, anger, and denial. This is where the Populist movement took root, with its railing against banks and railroads (Charles Ingalls joined the party in 1892, and a relative of Laura’s and Almanzo’s old friend Cap Garland spoke at the party’s Omaha convention–p. 165), but a “profoundly, painfully, and ineradicably personal” mix of “guilt and resentment” took root as well, which continued from the devastating Panic of 1893 all the way through the to Great Depression and beyond, and probably still gives life to much reflexive, rural anti-government feeling to this day (pp. 392, 454).

In retrospect it seems clear that this country made a terrible mistake in collectively grafting–whether intentionally or otherwise–the Jeffersonian agrarian ideal of the citizen-farmer to a natural and social context where “virtually all the land best suited to small-scale agriculture in the United States had already been taken.” Moreover, the marginal farming land which remained was essentially given away for free (thanks to federal military action taken against the indigenous inhabitants of the land, and thanks to an infrastructure mostly built by railroad monopolies benefiting from British money), usually to disconnected, often impractical individuals–“Pa was no businessman,” Wilder once admitted; “he was a hunter and trapper, a musician and poet”–who were themselves usually without the sort of cooperative and familial connections that were essential to the few actually successful farming homesteads of the late 19th century Great Plains. The result…well, as Fraser concludes, the result for over a million white immigrants and settlers during the first 30 years of the 1862 Homestead Act who failed and fled–as Laura and Almanzo eventually had to, relocating to Missouri after a new catastrophic years as newlyweds in the Dakota Territory–was that “they were bound to fail” (pp. 163-164, 186, 391). All of this has had, I think, an almost entirely negative contributing effect on the ability of many of us Americans to understand and thus govern ourselves.

“Almost entirely negative”–but not absolutely so. Because it was, for all its costs, the luring of unprepared people out into what was, through much of the 19th century, widely derided as The Great American Desert, which gave many Americans, as part of our received memories, a stark vision of this spare, flowing, expansive part of North America as both strange and beautiful, alienating and entrancing at the same time. It is that vision–and, perhaps most importantly, the realization of the vision’s passing, its conceptual (if not literal) closing with the arrival of the white settler–which does connect at least some of us together, as well as connect us with an occasionally usable past. Willa Cather is one of these connectors, as is the aforementioned Hamlin Garland–and, of course, Wilder herself. Fraser underscores repeatedly that Laura’s memories of the Great Plains inspired and haunted her until the day she died. Fraser discusses my favorite Little House volume, By the Shores of Silver Lake, which re-imagines the Ingalls’s move to the new settlement of De Smet, North Dakota, as “Wilder’s adolescent book”:

She had been trying to recapture that evanescent time in Dakota Territory her whole adult life. An account of her family’s isolated first winter on Silver Lake figures among the earliest surviving fragments of her writing, perhaps dating back to 1903. She had never forgotten the sight and sound of wild birds migrating across its marshes or the image of wolves on its shores. She had felt in her core the last of the wilderness passing into oblivion and mourned its disappearance, making the loss a leitmotif of her books as it had been in her father’s life. She labored over her drafts of the “Wings Over Silver Lake” chapter, her farewell to the soul of a place that would be erased by railroads, towns, and agricultural development (p. 408).

Well said–and yet, my favorite passage from By the Shores of Silver Lake, the one I can remember recognizing decades ago as the work of an author trying to recreate the dawning of a deep realization, the grasping of an insight, by a child, has a subject matter pretty much antithetical to that rapture of wilderness. Having read Fraser’s biography, I wonder where Lane’s (by then rather dogmatic) individualism ends and Wilder’s actual memories begin in this passage which stuck with me. Still, whoever ultimately put the words together, the power they contain, their narrative of a 15-year-old girl seeing, for the first time, her species as capable of changing the world, still rings out strongly. It’s from the earlier chapter “The Wonderful Afternoon,” in which the young Laura is taken by her father, against her mother’s wishes (which apparently was primarily due to the fact that “the workmen relieved themselves in the open air”–p. 406), to watch the railroad built:

The whole afternoon had gone while Pa and Laura watched those circles moving, making the railroad grade. It was time to go back to the store and the shanty. Laura took one last, long look….

First, someone thought of a railroad. Then the surveyors had come out to that empty country, and they had marked and measured a railroad that was not there at all; it was only a railroad that someone had thought of. Then the plowmen came to tear up the prairie grass, and the scraper-men to dig up the dirt, and the teamsters with their wagons to haul it. And all of them said they were working on the railroad, but the railroad wasn’t there. Nothing was there yet but cuts through the prairie swells, pieces of the railroad grade that were really only narrow, short ridges of earth, all pointing westward across the enormous grassy land….

There was no railroad there now, but someday the long steel tracks would lie level on the fills and through the cuts, and trains would come roaring, steaming and smoking with speed. The tracks and the trains were not there now, but Laura could see them almost as if they were there.

Suddenly she asked, “Pa, was that what made the very first railroad?”

“What are you talking about?” Pa asked.

“Are there railroads because people think of them first when they aren’t there?”

Pa thought for a minute. “That’s right,” he said. “Yes, that’s what makes things happen, people think of them first. If enough people think of a thin and work hard enough at it, I guess it’s pretty nearly bound to happen, wind and weather permitting.” (Wilder, By the Shores of Silver Lake [HarperTrophy, 1971], pp. 104-106)

Fraser’s tremendous documentation and synthesis of Wilder’s journey, both internal and external, makes it pretty clear that “wind and weather,” and much else besides, are far less “permitting” than we who are moved by the Little House myth usually allow ourselves to admit. These were men and women and children, whole families, that too often arrived without any local “knowledge of the place,” as Wendell Berry would put it. The results were usually sad, and frequently appalling in their costs. Yet somehow, sometimes, a few of them really did actually manage to change the face of the land in a way which endured, creating through their efforts a place, a home…though usually only for those who followed them, not for themselves.

For example, the centerpiece of my university, and the building in which I teach and work, is the Davis Administration Building. It was built to hold the entirety of a proposed Garfield University from 1886-1888; at the time of its completion, it was the largest educational edifice in the United States west of the Mississippi River. Garfield University was bankrupt by 1890 though, and through the following decade this monument to something a group of dedicated Kansas settlers had “thought could happen” stood abandoned on the flat scrub plain west of Wichita. But then came a wealthy philanthropist from St. Louis, who purchased the whole lot and gave it to the Kansas Society of Friends, which opened Friends University in 1898. So all is well that ends well, right?

For example, the centerpiece of my university, and the building in which I teach and work, is the Davis Administration Building. It was built to hold the entirety of a proposed Garfield University from 1886-1888; at the time of its completion, it was the largest educational edifice in the United States west of the Mississippi River. Garfield University was bankrupt by 1890 though, and through the following decade this monument to something a group of dedicated Kansas settlers had “thought could happen” stood abandoned on the flat scrub plain west of Wichita. But then came a wealthy philanthropist from St. Louis, who purchased the whole lot and gave it to the Kansas Society of Friends, which opened Friends University in 1898. So all is well that ends well, right?

Well, my judgment differs depending on if you ask me as a political theorist, a Kansan, an educator, a husband and father, or more–we all, like Walt Whitman, contain multitudes after all. So in conclusion, let me say that I can’t recommend Prairie Fires, whatever its small limitations, strongly enough; it presents the life and perspectives of an exceptionally multitudinous woman, and her perhaps even more varying daughter, in a way that helps one see through all their losses, reversals, and denials, to grasp the dreams and aspirations which animated them through all of the above. Not all dreams and aspirations are equally defensible, to be sure, and taking seriously what community and place and economic and environmental (to say nothing of psychological!) limits really mean ought to give all of us pause as we contemplate our attraction to the Little House myth. But the attraction remains, if only because the world Laura Ingalls Wilder saw and remembered is a world continuous with our own present moment. Wilder herself, with her daughter’s essential help, made sure of that continuity. She made a myth, and that myth–of pioneers and privation, of “the grasses waving and blowing in the wind, the violets blooming in the buffalo wallows, the setting sun sending streamers through the sky” (p. 515)–belongs to us all. Or at least, every time I take my bike out on a long, straight summertime ride towards that abiding, waving, prairie horizon which reaches all around me, it belongs to me.

7 comments

Brian

Thank you for the review.

Another quick question, if I may, before I just go find the book finally and read it–I’ve always thought that the Laura-Almonzo relationship would be a great subject for all sorts of discussions on past and current issues regarding women, family, etc. For instance, should we feel it a tragedy that Laura “drops out” of school to get married? That this incredibly smart girl ends her education to be “only” a farmer’s wife? Or should we view it as a tragedy that in today’s world she never in a million years would have married someone so clearly her “intellectual inferior” and so would have missed out on what seems to have clearly been a long and happy marriage? So the question is, does the author discuss their relationship in anything like any of these terms?

Russell Arben Fox

No, she really doesn’t discuss the Laura-Almanzo relationship much at all, and that’s a shame. But it’s not a shame that rests of Fraser’s shoulders, I think; it’s more a shame of the bare facts of their lives: Almanzo basically never wrote anything down, thus giving Fraser next to nothing to go on. And in all of Wilder’s hundreds of pages of notebooks and draft manuscripts and letters, there apparently were relatively few times she talked about Almanzo as himself, or her feelings for him. Of course, she did get him to talk about his youth; Farmer Boy couldn’t have been written otherwise. But whether she considered her husband beneath her or above her, etc., I didn’t see anything in the book to support a judgment either way. Wilder definitely had opinions about a woman’s place (she was uncertain giving “uneducated” women the vote was a good idea, for example), and it’s clear that she was deeply divided and torn over both her love of the family who raised and her pride at having gotten out of North Dakota and away from all them alive and not on the dole. But what role her husband played in her thinking about herself? The biography really doesn’t say, I think.

Brian

One could think of these questions either as how Laura would think about them, and how we should think about them. Clearly if you would have asked Laura what she thought about marrying a man who was her clearly her inferior who held her back from achieving her full potential, she would look at you like you had two heads, since she was not burdened with our modern notion that academic interest and achievement are equivalent to merit. So it sounds like the author wasn’t so much concerned with these topics, but I think it would make for some good material for FPR…

Russell Arben Fox

Yes, Fraser looks very closely at many of Wilder’s “As a Farm Woman Thinks” columns, and fits them into a timeline of Wilder’s development as a writer, as well as the development of her literary relationship with her daughter. I can’t summarize the whole thing here, but suffice to say Fraser–and I–agree with you; the notion (mostly promoted by Lane’s acolytes decades ago) that the daughter was the actual author of the Little House books simply doesn’t stand up to a close scrutiny of the letters and draft manuscripts they send back and forth to each other. Lane played a big role in the beginning in helping her mother figure out how to write, and figure out what kind of way to the tell the stories she wanted to write, but after the first few books, while Lane contributed to contribute ideas and passages, Wilder was mostly producing them on her own.

Brian

“Wilder’s fictionalized recreation of her pioneer childhood resulted in not only one of the great classics of children’s literature”

Oh, I’d say it’s a good deal more than that–to me she arguably wrote The Great American Novel.

And in Little Town on the Prairie, in the Fourth of July chapter, she writes perhaps the most perfect summary of America ever put to paper:

And Laura had a thought. The Declaration and the song came together in her mind and she thought: God is America’s king. Americans are free. They have to obey their own consciences. This is what it means to be free.

“Our father’s God, author of liberty —”

The laws of Nature and of Nature’s God endow you with a right to life and liberty. Then you have to keep laws of God, for God’s law is the only thing that gives you a right to be free.

Russell Arben Fox

Fraser makes the argument, backed up by manuscript drafts, that that scene is pretty much entirely the work of Lane, not Wilder, but still, I agree: it’s a great moment, a wonderful expression of Puritan exceptionalism mixed with pioneer individualism.

Brian

Does she talk much about Laura’s newspaper & magazine writings? I’m not a scholar, but to me it seems clear from reading the limited amount of them that have been published that you can see her development as a writer of the books from the very episodic nature of Little House in the Big Woods, similar in many ways to the sort of writing she did before, to the much more novelistic later books. Which has always made me a bit skeptical of the revisionist claim that Rose somehow was more responsible for the books than Laura was, since her newspaper and magazine writings show an already very capable literary talent.

Comments are closed.