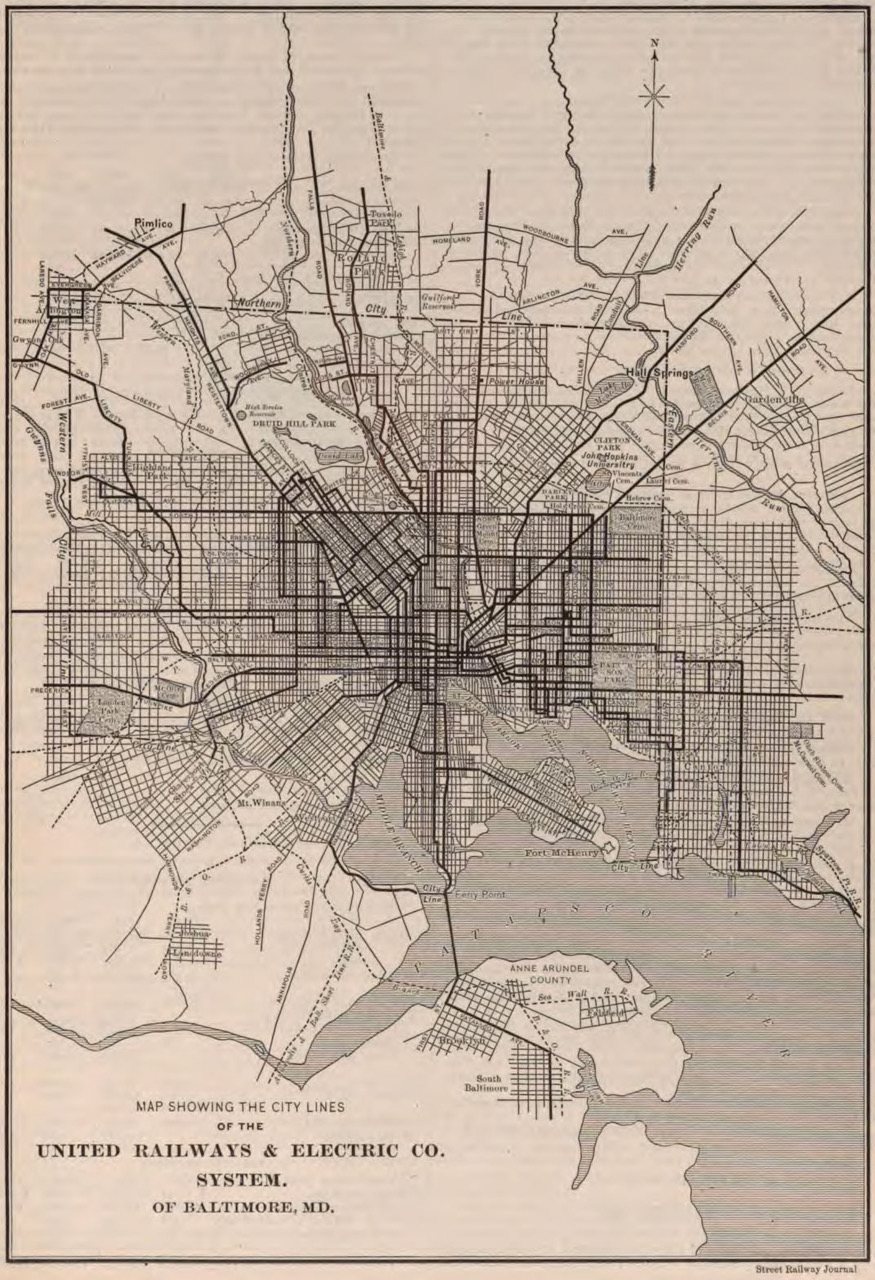

Although you would hardly know it today, Baltimore was once a city of streetcars. Crackling densely across the city’s center like fissures in old pavement and then sprawling thinly outward into the suburbs, a map of old streetcar lines is like a guide to what, to this day, constitutes “Baltimore” and what does not. Lay that map over the contemporary city and marketers might find a guide to where to send Orioles and Ravens adverts versus those for the Washington teams to the south and Philly’s to the north.

Baltimore is hardly unique in this sense. Most major and even middle-tier American cities had extensive streetcar networks throughout the first third of the twentieth century. Though in many cases smaller geographically then today’s rambling, partly suburban cities, early twentieth-century urban centers were large enough to need some form of transportation network long before the automobile had extended its imperious reign across the nation.

Horses drew the cars first. The tracks in the street reduced the burden on the animals, allowing them to pull much larger carriages than before and therefore charge less than privately hired cabs. Although this democratized urban transit in a new way, horses were not without their drawbacks. They dominated cities in the way cars and trucks would later. Walking into a nineteenth-century American city was a challenging sensory experience, and horses provided many of the most malodorous notes (as well as the prospect of being run over). Their waste and their carcasses—often left lying on the side of the street like garbage during a sanitation strike—contributed not just smells but various microbial terrors to urban life. Contrary to what one might think, the invention and implementation of the locomotive actually increased the use of horses in the United States, as once goods and people were off the train there was no alternative but the horse for local point-to-point transport.

Over time, streetcar companies developed other less organic forms of motive power. One early method was the cable car—for which San Francisco remains famous—where giant steam engines would continuously pull lengthy cables across a city. The cars would release and latch onto the cable to stop and go. Cable cars were made obsolete by the development of commercially viable electricity generation and, with that, the electric streetcar. By the early twentieth century, electric streetcar networks were spreading across hundreds of American cities and into the surrounding countryside.

But by the 1950s they were almost entirely gone. The Great Depression played a role in this, forcing many lines to close in the 1930s, but of greater significance was the societal adoption of the automobile. This was by no means an inevitable decision—the logical progression of one form of technology to the next—but a deliberate privileging of one type of transportation system over the alternatives.

The societal adoption of the automobile was by no means an inevitable decision—the logical progression of one form of technology to the next—but a deliberate privileging of one type of transportation system over the alternatives.

The car certainly offered many advantages to midcentury America, not least of which was aesthetic. Few things better embody the “American dream” of freedom and self-reliance than the automobile. It’s a true individualist, or nuclear family, form of transportation. The car held out the possibility that every American might have their own private “castle” in the ever-distant suburbs. It stood in sharp contrast to more collectivist ways of getting around at a time when anti-communism was all the rage. Freed from the noisy, crowded, and polluted cities of their parents, young families struck out for the country.

As government money poured into automobile related infrastructure and the tax system was adjusted to privilege suburban home ownership over urban renting, city administrators were forced to cut costs. Rather than updating aging streetcar infrastructure, cities turned instead to a less cash-intensive alternative: busses. In a number of cities, including Baltimore, this move was facilitated by National City Lines, a bus company owned jointly by General Motors, Firestone, Standard Oil, Phillips, and Mack Trucks. NCL bought up the streetcars and converted them to bus lines, making easy profits for its parents in supplying engines, tires, gasoline, and the like for the new transportation system.

And so, decades worth of capital investment was discarded—almost overnight—with a few well-known exceptions. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, it was those exceptions, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Philadelphia and Boston, that were the first cities to witness the urban renewal of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as young people rejected the suburbs their parents and grandparents had so readily embraced. Fixed, mass transportation networks are all but essential to thriving urban spaces. Those American cities that have returned from the mid-century brink without them have done so in spite of this, certainly not because of it. Uber and its competitors, the privately hired hansom cab returned in internal combustion form, has lately filled in the gap.

Bus networks have much to recommend them, of course. They are significantly cheaper to build and operate, easier to expand or contract, and significantly more diffused than any fixed transportation system. And, as critics of streetcars have demonstrated, busses are no less efficient in getting people around than other surface forms of transportation. All of which, including streetcars, are hindered by the same issues of traffic congestion, weather, and the like.

Yet, this focus on efficiency—economic or otherwise—misses the point, as such arguments often do. “Efficiency,” by its nature, is always a means, not an end in itself. Thus when one hears that word they should be alert to the real motives behind it. In this case, “efficient public transportation,” generally means “cheaper public transportation that allows for lower taxes and/or privatization” or something of that ilk. This concept of society and government, in which the only goal is to run the damn thing as cheaply as possible, represents a deeply impoverished understanding of what’s necessary for good governance, social peace, and human flourishing

It also ignores the many benefits, material and otherwise, of supposedly inefficient streetcar systems. A well-run and maintained streetcar network is a band of civilization spread across urban space. Unlike a bus, which quickly abandons the places it occupies, a streetcar line and its associated infrastructure is a permanent presence. Sure the car itself may leave, but the tracks and the platforms hold a promise, and speak of order, in a way the empty pavement behind a departing bus never does.

A streetcar line ties a given space into the rest of the city.

It was in recognizing the real, tangible value of these “soft” aesthetic artifacts that Jane Jacobs made some of her most important contributions. The way a space “feels” to people shapes, and even controls, their behavior. It might be just as easy for a criminal to steal a purse in broad daylight on a crowded street, but they are a lot less likely to do so than at night. While a streetcar line is never going to have the power of a restaurant with a patio, it still ties a given space into the rest of the city, even when the car is elsewhere. The tracks and power lines draw our mind’s eye away to the larger communal whole. Streetcars—like streetlamps—can make a place feel safer, more cared for, less individuated.

The marketers amongst us can surely explain the economic value of that.

1 comment

Brian

“Unsurprisingly, perhaps, it was those exceptions, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Philadelphia and Boston, that were the first cities to witness the urban renewal of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as young people rejected the suburbs their parents and grandparents had so readily embraced”

1. As far as I’m aware, this just isn’t true.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/04/why-is-everyone-leaving-the-city/521844/

2. On the one hand, I kind of like the repurposing the “urban renewal”, but on the other hand, since you brought it up, it would have been good to have expanded more on your note that “As government money poured into automobile related infrastructure…”, and a bit less on vague allusions to conspiracy theories about Big Auto destroying street cars. The fact is that as people fled cities for the suburbs, urban renewal programs in general decided that the answer was to destroy whole neighborhoods to build freeways, and to destroy entire swaths of downtown areas to build parking lots and shopping malls. This was done in many cases by mandates from state and federal governments–if you want this money, you do what we say and destroy yourself. In retrospect the obvious answer would have been to make living in the suburbs less attractive by making the commute to downtown work (when it still existed…) intolerable so that the benefits of suburban life would have had stronger tradeoffs. Alas, there is no turning the clock, or rebuilding what was lost. We can try to give decision making authority back to local cities and neighborhoods, since top down decrees were so disastrous, but in so many places there are no people or businesses left to build on.

Comments are closed.