We live in a time of political disruption. In the United States and around the developed world we are seeing nationalist and populist agitation against the established liberal order. While this is a cause of anxiety, it is also a moment of great opportunity. There seems to be both intellectual and political openness to challenging the ruling paradigm of liberal politics, consumerist capitalism, and internationalist foreign policy. In this anxious, frustrated age, we require diligence and prudence to guide this angst toward an edifying end. There are whiffs of authoritarianism in the air that should give pause to those who have some degree of sympathy with recent political upheaval.

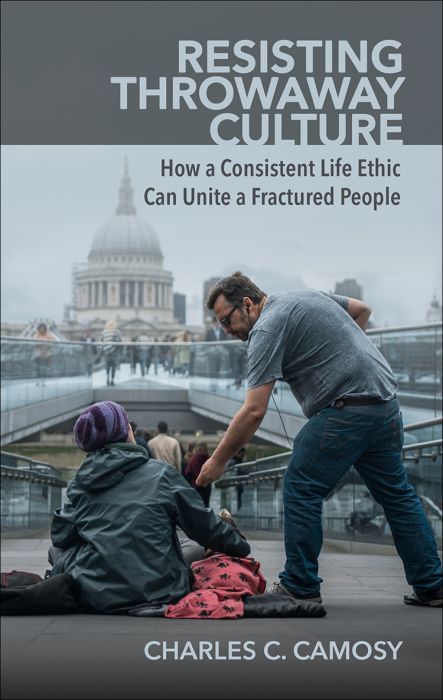

Enter Charles Camosy of Fordham University and his highly edifying new work Resisting Throwaway Culture: How a Consistent Life Ethic Can Unite a Fractured People. This iconoclastic book takes its titular phrase from Pope Francis, who defined “throwaway culture” as one in which “everything has a price, everything can be bought, everything is negotiable. This way of thinking has room only for a select few, while it discards all those who are unproductive.” In speeches and official statements, Pope Francis has repeated this idea, namely that our times are defined by utility and that which is found useless, even people who are found “useless,” are thrown away.

Camosy, inspired by the “consistent life ethic” (CLE) originally propounded by the late Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, seeks to turn the notion of CLE into a definitive public vision that resists that throwaway culture. The author applies CLE to a variety of topics such as human sexuality, reproduction (including abortion, surrogacy, and in vitro fertilization), poverty, animal rights, euthanasia, and state-sponsored violence (including war and capital punishment). He does so in a readable if slightly didactic style. One of the book’s many strengths is Camosy’s inclusion in each chapter of “objections” to which he responds. I found myself repeatedly thinking while reading, “But some people will say…” and sure enough, Camosy consistently anticipates the possible objection and gives a credible response. What is more, he even presents charts! The book’s appendix contains a schematic that lays out the basic principles of CLE and then graphs out how to apply CLE to the various matters discussed in the book.

Camosy’s book is timely: as ideological barriers are breaking down, people may be open to an ethic such as CLE that does not fit into our predetermined political categories. Camosy’s views on abortion and sexuality surely will make those on the left uncomfortable, while his application of CLE to issues such as animal rights and capital punishment may do the same to those on the right. Camosy notes that part of our throwaway culture is throwaway media, our tendency to value intellectual heat over light, as it is heat that sells. While we need not turn “something to offend all sides” into a fetish, it is at least one sign of creative, bold thinking to unflinchingly apply a consistent ethic in a manner guaranteed to challenge while doing so in a way that demonstrates intellectual humility and an appreciation for other views. Camosy has achieved this.

Camosy’s treatment of human sexuality as “throwaway” calls to mind Augusto del Noce’s diagnosis of the sexual revolution as a species of capitalism. Both value individual choice and fulfillment of desire above any other good. As William Cavanaugh has noted, our times are defined not so much by greed, the perverse attachment to things, but by waste, a perverse detachment from things. Jerry Seinfeld, in a riff on “power-flipping,” once joked that men are not interested in what is on T.V. but in what else is on T.V. That stands as a metaphor for the entire culture. The consumer culture, which includes our sexual culture, is about getting, consuming, and then moving on to the next thing. That’s why “new and improved” or “now with 10% more” are such regular advertising tropes. Take something old, repackage it, and sell it as if it is novel. Now imagine we are not doing that with toothpaste but with people and you get an idea of what throwaway sexuality is. One of Camosy’s great achievements is demonstrating how the general hook-up culture—reaching its apogee in Tinder—is mirrored in the more obvious forms of sexual violence decried by the #MeToo movement. The latter flows naturally from the former. When we see people as objects meant to satisfy our desires, rather than as persons created in the image of God and thus having essential dignity, we are more likely to treat them as just another disposable thing. Camosy notes the sexual colonialism of such institutions as the Gates Foundation who wish to export this sexual consumerism to less-developed countries. This itself is a form of violence.

Reproductive technology is another manifestation of this mindset. Perhaps an overall theme of Camosy’s book is the danger of applying the market mindset indiscriminately. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the arena of reproduction where human beings become a literal commodity. This is true of babies whose production may be purchased or with surrogacy, the purchasing of a woman’s womb. In a piece critiquing Clarence Thomas’s recent legal opinion that included a history of eugenics, Damon Linker opines that contraception has “no negative moral consequence at all.” While not wishing to wade in on the ultimate merits of contraception, Linker’s claim seems obviously false. Camosy ably shows that the reduction of sexuality to “choice,” including the choosing whether to have a baby or not, has repercussions far beyond the one-night-stand. The treating of a child as a thing to be purchased or chosen, rather than as a gift to be accepted, has profound consequences for how we see our fellow human beings, even those closest to us. Oliver O’Donovan, borrowing from the Nicene Creed, notes that human beings are begotten, not made. It is the act of begetting that ties us in nature to our children. The more we see children as a consumer choice, as a convenient commodity or an inconvenient one, the more we see them and humanity in general as objects in the throwaway consumer culture.

It is therefore somewhat disappointing that Camosy does not take on consumer culture in general. The modern imperative of consumer capitalism seems ripe for a frontal assault. The economic message of the book is latent rather than clearly stated. While various portions of Camosy’s book will offend particular sections of the political spectrum, the linking of consumerism to environmental degradation and sexual liberation would surely challenge the vast majority of Americans.

The latter chapters on the book, namely those on immigration and war, are provocative in the best sense. Camosy puts strong emphasis on abstract human rights. In the spirit of friendly criticism, here we might offer objections not anticipated by Camosy. Camosy considers the rights of individuals abstracted from the duties of sovereignties. In Plato’s Republic, it is the characters of Cephalus and Thrasymachus who argue for justice in the service of the particular. Justice is favoring one’s own over what is abstractly right. One can see the obvious error in this way of thinking. Conversely, when Socrates creates the city in speech he dangerously abstracts from the particular. In what many take to be a case of Socratic irony, Socrates seems puzzled as to why one might object to men and women wrestling in the nude or a system where children are taken from parents precisely because it is unfair that parents favor their own children over others. Socrates, by taking the argument to the point of absurdity, may be illustrating the error contrary to that of Cephalus and Thrasymachus, that of abstracting justice from actual human relations and behavior.

This goes to the subject of the duties of sovereign governments. People are not abstract rights bearing individuals. They reside in particular families, in particular places, with a particular history, and with particular governments. While it may be the case that Guatemalan grandmothers have the same rights and dignity as American grandmothers, is it the case that the American government has the same duties toward the Guatemalan nannas as it does American? Camosy demonstrates powerfully that many Latin American governments are damnably neglectful of their duties toward their citizens, even the duty of basic public safety. To what extent does the neglect of duty by one sovereignty create duties on the part of other sovereignties? Here Camosy treads on dangerous ground. If America has the duty to respect the rights of immigrant Guatemalans, does America then gain the right to interfere in Guatemala so as to protect those Guatemalan grandmothers better than their own government? This is at least part of the argument for American military intervention in places such as Bosnia and Iraq. If those governments were brutalizing their populations, and America has the duty to accept refugees from those countries, does American gain the right—or even the duty—to correct the problem at the source?

Camosy criticizes the American government for being hesitant in accepting refugees from war-torn Syria. He correctly notes that America deserves some of the blame for the instability causing the Syrian civil war. One must ask, however, to what extent is the tragedy of Syria the fault of America, and to what extent is it the fault of Syrians? Surely Bashir Assad, propped up by Russia, deserves some blame, no? He is the sovereign of Syria. Surely he is more to blame for gassing his own citizens than is the United States. Yes, American policy contributed to the rise of ISIS. Let me suggest another group to blame. ISIS. The members of ISIS are moral agents. They are not puppets of American foreign policy. Whatever enabling conditions for the rise of ISIS we can put at the feet of the United States, the United States is not the one raping women and beheading apostates. Camosy is at risk of infantilizing the residents of our world’s most poor and oppressive nations. To the point, who is responsible for vindicating those whose rights are being violated? There is some evidence that, yes, a large influx of immigration lowers wages for native workers and, as per Robert Putnam, decreases social cohesion. Might a responsible government think twice about how many immigrants and refugees it accepts and how fast?

Lest I be misunderstood, I wish to defend neither American Middle East policy nor American immigration policy, certainly not as the Trump administration as implemented that policy. I only wish to point out that excessively abstracting human beings from place and history glosses over certain realities, messy though they may be. Camosy’s eagerness to critique American policy—surely worthy of criticism—also runs the risk of relieving other governments of their own duties to their people.

This is why discussing hierarchies of duties might be more fruitful than playing the trump card of abstract rights. The good of rights talk is that it undermines the unjust use of authority. This appears to be Camosy’s aim. And to be fair, he doesn’t explicitly use the language of rights, but in his evocation of abstract dignity he argues within that ethos, with the aim of limiting the evils of throwaway culture. The problem, however, of rights talk is that it tends to indiscriminately undermine all authority, legitimate and illegitimate. Instead of pleading the rights of Guatemalan refugees, let us think about our duties as individuals and as citizens toward those refugees. We must balance those duties against other duties, for example duties to the rule of law or to providing for current American citizens.

Personally, I am conflicted over many of these questions of sovereign duties versus duties we have as, for example, Christians. My questions for Camosy are honest as I am not sure I know the answers. One of the many virtues of Camosy’s book is that he opens up these matters for discussion and gives a rubric for discussion based on very firm ground, that of a consistent life ethic. One is reminded of Just War theory. Just War theory does not exist to provide decision makers (including us as citizens) with a checklist by which we can determine in some formulaic fashion whether a military action is just or not. It serves as a guideline to get us asking the right questions prompting us toward the goal of avoiding injustice. Camosy’s excellent book does the same, and as such, it deserves to be widely read. May it be the beginning of many fruitful arguments that lead us to rightly value the precious gift of life.

3 comments

Jackie

As one in the depths of ‘ruled ‘, and not privy to all the information you may have, please give me some additional specific details that would explain what is so wrong about the trump administration’s immigration policy and position? I have been under the mistaken assumption that he is abiding by the laws already in place.

John C Medaille

This is a real insight: “our times are defined not so much by greed, the perverse attachment to things, but by waste, a perverse detachment from things.” Capitalism is characterized by fulfilling desires, not needs; the size of the garbage dump is the true measure of its success. Which is why no examination of culture can be complete without an examination of its economic system.

As far as America’s responsibility for instability and violence around the world, the fact that others also bear some blame does not negate or cancel our obligations.

Nicholas Skiles

Hear, hear!

Comments are closed.