A place on earth is a deep down need, like that of transcendence, for the human person. All of us yearn for a place that we can call home, an ordered and stable locus around which our lives revolve. We desire that place to be both our point of departure and our destination, the place from which we start, as T. S. Eliot claims in “Little Gidding.” And yet we are, all of us, to greater or lesser degrees, exiles in the world.

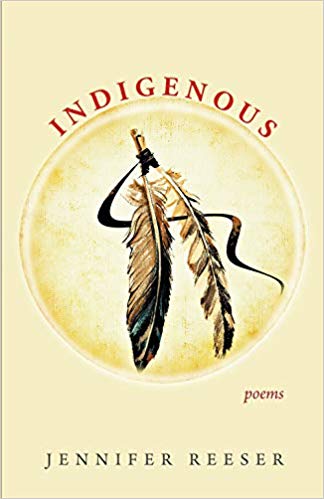

Exile marks Indigenous, Jennifer Reeser’s latest collection of poems. After reading the poems, it becomes quite clear that “indigenous” is the most apt word for the title of a book that attempts to make sense of the human need for a homeplace and the reality of exile, a reality intensified by Reeser’s Amerind and Anglo-Celtic heritage. Throughout the collection she is caught, torn, and thrown about by the anxiety of existing on the threshold between the two bloods commingling in her veins. What sets Reeser apart, though, from many other Amerind poets and writers is that she does not see herself occupying a border or a boundary or even as coded through a so-called “liminal” discourse. Rather she clearly and directly positions herself as a bridge between the Amerind and Anglo-Celtic cultures.

Thinking of herself as a bridge allows for an incredibly effective embrace in the poems of the past, her past as well as the larger historical narrative of Amerind-European relations. This inclusiveness is made all the more effective and moving by Reeser’s insistent use of traditional English poetic forms (as well as a traditionally French form called rondeau). In fact, she perfectly models her ethnic hybridity in a poem titled “Half-breed,” a poem composed in iambic, rhymed couplets. She tells us,

My blood—all Indian while still all white—

Mixes and balances, a dual birthright.

I am your bridge. I am, as well, your breach.

Hear me, and heal—I’m none of you, and each.

By considering the mixing rather than the distinction of her birthright, Reeser welcomes readers into her experiences of the past and present state of Amerind-European relations. (Several poems eviscerate the EPA and federal government about the Río de las Ánimas disaster in 2015, and several more consider the pacifism, violence, and violation of sacred lands due to the tensions surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline and Sioux protests of its construction.)

Without shying away from the present injustice still being perpetrated by the U.S. government on Amerind peoples, Reeser still finds ways to invite readers into indigenous experiences rather than lambast readers for the violent history of the U.S. Her exhortation to both Amerindians and whites to hear her and to work toward reconciliation is an attempt to break down the perceived division between colonizer and colonized, to help us to recognize that we are brothers and sisters on this earth.

Indeed, another major motivating theme throughout Indigenous is the re-tethering of the human person to the earth, to a particular place on earth. Reeser achieves this through the marriage of Amerind story, personal history, and national history, and all of these things are brought together in her excellent handling of traditional verse forms. What this allows for Reeser, as she dances through villanelles and marches through sonnets, is the very bridging she aims to do with the collection. Several poems are written only using sounds that exist in the Cherokee language, but they are written using forms developed with English (and the poems themselves are written in English). By foregrounding the commonalities between the languages of these two peoples, Reeser shows how much more aligns us than divides us—in particular, the need for limits and the need for grounding ourselves in place.

Though she was born in Louisiana and later moved to Oklahoma (where she now lives), Reeser speaks in many poems about East Tennessee, about locales that make up the Appalachian mountains and the ancestral land of the Cherokee from whom she is descended. Chilhowee Mountain and the Great Smoky Mountains feature prominently as anchors for her present experience—they are the past that dictates the future. She considers this tension in a poem enigmatically titled “Raised on Rogers.” Towards the end of the poem, composed entirely in metered, rhymed tercets, Reeser gives her meditations a moral force by placing herself, as Burke would have acknowledged, as an inheritor of the past and guarantor of the future:

Now I have inherited this land,

Finally, I hear and understand

What they meant, by that reserved command

Graven on my anima from birth:

Hold to good with all that you are worth;

Hold—though it be nothing but dry earth.

The land is her inheritance—and the traditions that arise from that land, from that people who lived on and in that land. Holding to good, for Reeser (and hopefully for all of us) is tied directly to an understanding of self that is tied to our common and personal inheritances. We, all of us, inherit the land, and if we choose to follow Reeser, that inheritance is inextricable from the command to hold fast to goodness. What this means, especially in Indigenous, is to prescribe limits, to consider the ties that bind together, the ties of tradition, of exile, of form, of brotherhood and sisterhood alongside one another. It is a hybrid, sacramental understanding of the earth and matter and of being in the world. She seems to say that even if the earth of Chilhowee is dry or the trees of the Smokies are stunted, we must cherish them because they remain good.

They are the places that draw her as she attempts to consider what it means to be indigenous to a conquered land—and this continent is undeniably a conquered land. But rather than let that be an excuse for turning her poetry into versified political propaganda, Reeser insists on the bridge and the breach even as she makes visible the seemingly perpetual imperialistic practices of a centralized federal government. Both the bridge and the breach are connections: the former as a means across what is impassable otherwise, the latter as an opening allowing passage through those walls built by ideology, political practices, religion, and cultural and economic values. Let us let the bridge stand for a grounding in place—a founding of a home in the midst of our exile. Let the bridge and the breach invite us to a place where there can be healing, where inheritance can be restored, where possession can replace dispossession, and where reconciliation between brothers and sisters on earth can begin.

And the tentative nature of that healing cannot be stressed enough. As the dualities in the form and content of the poems show, Reeser recognizes that any and every act requires a response, especially (in the case of the literary arts) language acts. George Steiner calls this, rather coyly, the response-ibility of the writer to what she has read, to what has come before, and to what will come after. Reeser makes an offer, a gesture, and we in the reading of it become responsible for it, become answerable to it. That Reeser has chosen to make her response to the past and her past in traditional forms and traditional content (both European and Amerind) tells us much about how she envisions that healing happening. Let us tie ourselves, she seems to say, to our pasts, to those places and people that have made us, so that the future can be made from it and made in song.