Akron, OH. Over 2,400 years ago the giants of the Axial Age—Buddha, Socrates, Confucius, Zoroaster, the Jewish prophets, and the originators of the Upanishads—all dramatically changed their respective cultures in such diverse ways that it is difficult to say what they had in common. However, since the idea of an Axial Age was first proposed by Karl Jaspers in 1948, it has generally been described as a breakthrough in consciousness and compassion. Karen Armstrong, for instance, in the concluding chapter of her book The Great Transformations, writes that “the Axial sages put the abandonment of selfishness and the spirituality of compassion at the top of their agenda.” But that was not the highest priority for all the Axial prophets and sages. Zoroaster and the Jewish prophets, for example, were most concerned with one’s relationship with God. On the other hand, it can reasonably be said that all the Axial Age teachings and practices did respond to the alienation caused by the increased scale of early civilizations, which was disruptive to the natural harmony humans had previously known. The social structure through which humans evolved was far more egalitarian. Early people shared our egotistical desires, but within small hunter-gatherer clans adults were able to form coalitions to prevent individuals or small groups from dominating the majority.

As the clans became tribes and then city-states, class stratification became more pronounced. Slavery and polygamy also became more common. Early states developed oppressive, hierarchical social structures because the networks of kinship bonds formerly used to allocate authority were no longer adequate for holding together these larger, more complex societies. Successful competition and warfare amongst neighboring states also required a concentration of power that culminated with the priest-kings of the first civilizations, whose divinity was thought to maintain society’s relationship to the gods. But, even as kings asserted their divine authority with ever grander rituals and displays like the pyramids, they had to counter the natural desire for the equality between families that had been lost when tribes merged to form states. According to the Robert Bellah in his book, Religion in Human Evolution, the first kings responded to these questions about their legitimacy by presenting themselves as powerful warriors who defended the state from the barbarians on the frontier and rebels within. As these societies matured, the king was increasingly idealized as a compassionate figure who would bring about a just society. In Egypt the king was referred to as the defender of justice, in Mesopotamia as the good shepherd, and in China as the mother and father of the people. At the end of the Old Kingdom in Egypt (2649-2150 B.C.), the pharaoh Ankhtifi had inscribed an account of his own justice in which we can see early signs of the Axial Age:

I gave the hungry bread

And clothing to the naked,

I anointed the unanointed,

I shod the barefoot,

I gave him a wife who had no wife

I rescued the weak from the strong.

A similar movement is visible in Mesopotamia in the 18th century B.C. with the legal code of Hammurabi which also proclaims the king’s justice:

The great gods have called me, and I am indeed the good shepherd who brings peace, with the just scepter. . . . By my wisdom I have harbored them. In order to prevent the powerful from oppressing the weak, in order to give justice to the orphans and the widows.

The struggle to maintain legitimacy led to an increase in the value that culture placed on human life. An inscription during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (2030-1640 B.C.) connects this increased valuation with the idea of a creator god who, like the God of Genesis, made humans in his own image:

He made breath for their noses to live,

They are his images, who came from his body,

He shines in the sky for their sake;

For them he made plants and cattle,

Fowl and fish to feed them.

Once the king’s claim to be a protector of the common people became a basis for legitimacy, it also became reasonable to question the king’s justice. Manifestations of power, wealth, and external glory alone were no longer understood to always represent divine will. The sages of the Axial Age challenged the prerogatives of the elites at great risk to themselves. According to Bellah, they were teachers, who offered a vision of divine justice that emphasized equality. For example in China, the “Way” of shamanic Taoism was interpreted by Confucius to mean the way of the “gentleman.” The myths of the ancient gods were humanized and converted into stories about the first emperors. More importantly, Confucius reinterpreted the term “junzi,” or “gentleman” from a hereditary title to the designation of a moral elite available to everyone. This was the beginning of a radical change in China that would eventually lead to a culture in which Confucian scholars determined whether leaders were acting in conformity with heaven’s mandate. For two thousand years, the empire was ruled by an intellectual elite devoted to Confucian thought. Access to political power came from competing successfully in the civil service examinations, which were open to all. Until modern times, only a few city-states could claim to have such an open and sophisticated system of government.

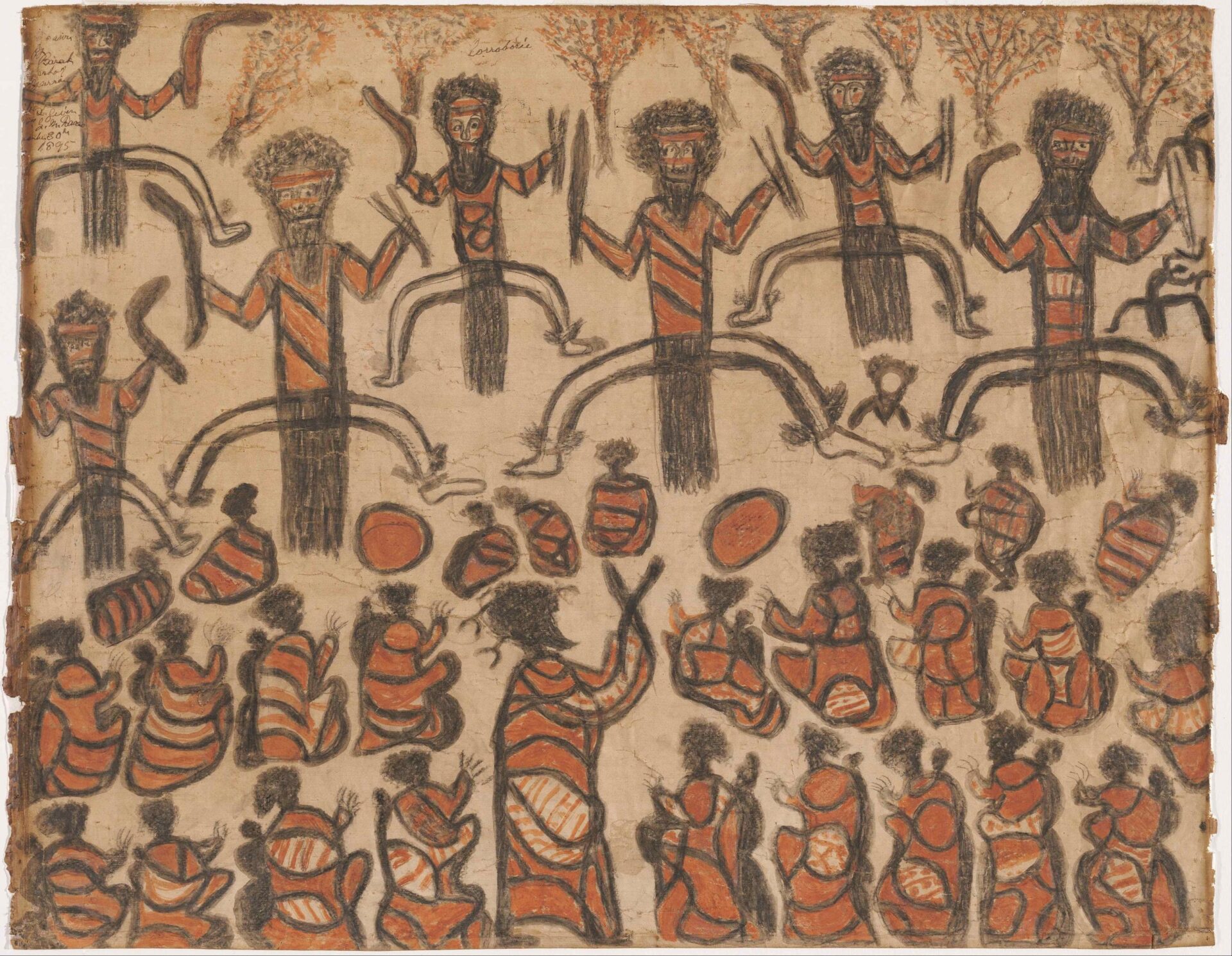

However, the Axial Age was about more than equality—it was also a return to the intimacy that each person can have with the divine. Hunter-gatherer groups lived as close to the sacred as possible in order to find constancy and reality in the chaos of the natural world. For them all significant actions including hunting, farming, sex, eating, birth and burial occurred in imitation of the myths so that people could act in conformity with the gods who were thought to be immediately present. Early people, like the Australian aboriginals, understood specific places such as a stream or mountain as participants in rhythmic and abiding events known first-hand by their ancestors. In the Axial Age this intimacy and broader participation were renewed but through different means. Communion with the transcendent—whether through meditation, ceremony, or chanting of the psalms—was made more direct and more real. The immediacy of a reinvigorated relationship with the divine was carved into the culture by the Axial Age teachers and prophets who taught ways of acting and thinking that allowed for a deeper sense of communion with the divine for all members of the new religious communities. This reincorporation of religious life into daily life vivified civilizations to such an extent that even now our lives are oriented by these traditions.

The Axial Age promised the reinstitution of a revitalized sacred primitive community. However, this ideal was challenged by an equally powerful movement in favor of individual fulfillment and accomplishment, also rooted in human nature, which was especially championed by the ancient Greeks. Renaissance, Enlightenment, Communism, Fascism—all were struggles between individualism and the desire for closer community, but for a host of reasons, individual freedom has won out over community in the contemporary West. The empowering of autonomous individuals has provided a great bounty; however, there is an imbalance we experience in our angst and in the degradation of the environment. The individual has been freed from the censure of family, neighbor and Church, but the void has been filled by large and distant bureaucracies. The extent of our loss has not yet become apparent to our intellectual and political elites. An exaggerated belief in our ability to order society based on our individual reason has caused our politics and our spirituality to become self-centered and small. We have lost our intuitive sense that the wisdom and framework to cope with life’s challenges are culturally endowed. We believe we are liberated because we act spontaneously and are unfettered by the traditions that guided older societies. We believe that this liberation allows us to be spiritual in a more genuine fashion. But community can only flourish within a network of traditions and shared culture. Undoubtedly, the thick crust of custom can be oppressive and stultifying, but a people freed from tradition cannot be grounded by political action and over time will be ruled by their appetites and the whims of the mob. Our disregard of tradition and community has left us alienated and estranged compared to more traditional societies that rely on a web of family, community, and religion.

Meaning in life has always required a relationship to something transcendent and lasting, but religion is more difficult today when our technology-assisted lives are so autonomous. The traditions that sustain community and religion dissipate when individuals do not need their neighbors to raise and educate the young, to care for the needy and the elderly, to maintain the safety and environmental health of the neighborhood, or to earn a living. Day-to-day life cannot be adequately related to culture and community unless the authority of the state and large institutions is ceded to the local community so that people can again be responsible for their neighbors. Only in smaller associations is it possible to achieve the immediacy and trust that allow for meaningful relationships with mutual appreciation for the unique gifts each person offers. When people are given real responsibility for outcomes, they become engaged participants with the ability to renew communities. The sacred community must be reimagined to fit our circumstances and the scale of modern existence. Only then will we be able to hear the words of our prophets, which now echo hollowly in our autonomous society.