Leeds, MA. In 1965 Thomas Merton, after long waiting, moved into his hermitage on the grounds of Our Lady of Gethsemani monastery near Bardstown, Kentucky, where he had lived since 1942. A few months earlier and eighty miles north, Wendell Berry took apart a cabin that had belonged to his uncle and rebuilt it as his writing place, a kind of hermitage of his own, which James Baker Hall describes as “not just a quiet place, it was a place of quiet.”

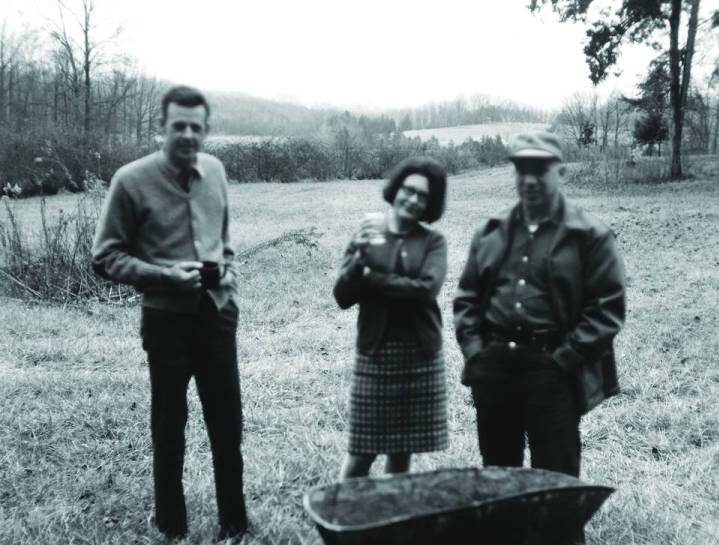

Merton and Berry met, it seems, at least once—on December 10, 1967, exactly one year before Merton’s death. Wendell and his wife Tanya, poet Denise Levertov, the photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, and his wife Madelyn all met at Gethsemani for lunch. The meeting seems to have been pleasant but exhausting for Merton, who wrote in his journal for that day “I am hoping this next week will be quiet—a time of fasting and retreat. Too many people here lately.” It is possible that they met before this, as their letters display a certain familiarity—Berry mentions that he had his publisher send a copy of one of his books (possibly Openings) to the hermitage. Berry addresses his first letter to Fr. Louis, Merton’s religious name, which suggests any earlier meeting may have been under more formal circumstances.

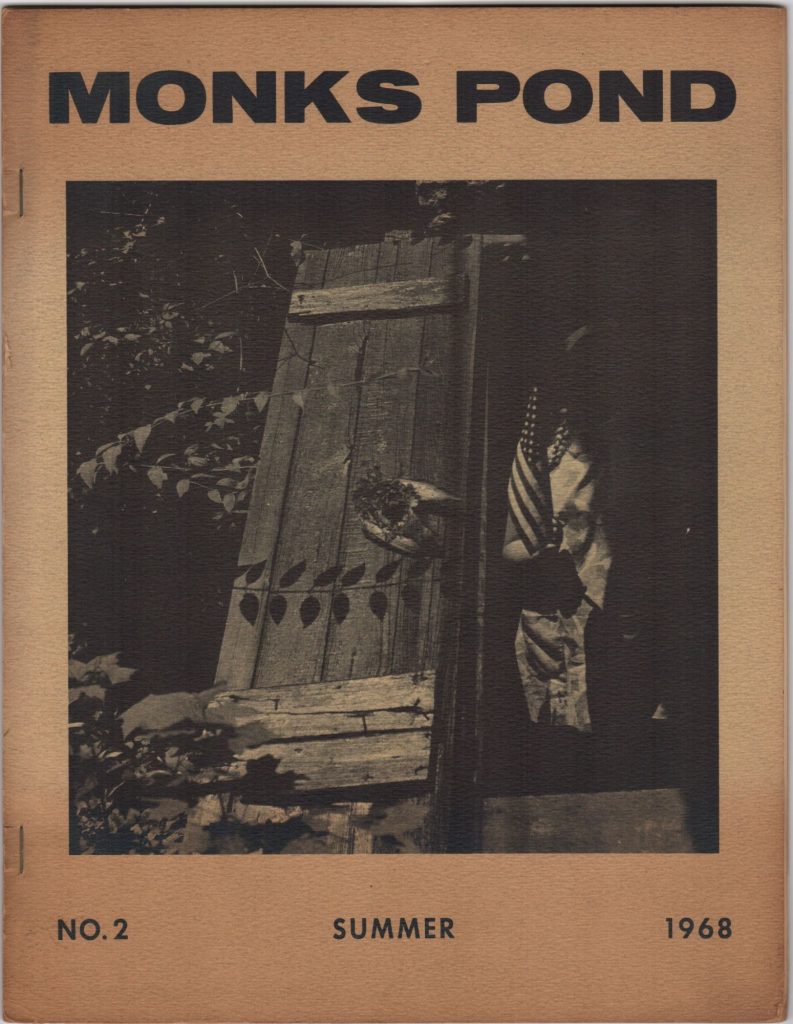

The other letters are mostly to do with Merton’s magazine Monk’s Pond, which Berry had sent some poems to. “Maybe I am losing all my friends by failure to answer about Monks Pond. . . .” Merton writes in his journal, “Must write Jonathan Greene, Wendell Berry, etc. etc. Will try to get the second number lined up today. First is stalled in Cassian’s printshop. Liturgy choking every press.” He dates Berry’s letter a day earlier, saying he’d run most of the poems in the next two issues and had done some toggling with others. “This is probably a hell of a way to edit a magazine,” he says. A picnic at Gethsemani is suggested for around Easter—Merton, by the way, had been looking forward to the solitude of that Lent. Berry, however, would be on the West Coast, he says, and can’t make it. They would never meet again.

Berry wrote in one of his letters to Merton that “you are one of the few whose awareness of what I’m doing here would be of value to me.” He is acknowledging that he and Merton lead lives of similar mission, lives shaped by work and silence. Given the enormous development in Merton between The Seven Story Mountain and Zen and The Birds of Appetite (which he was finishing when he met Berry) who knows how he would have changed further if he had lived longer. Throughout the 1960s, though, he and Berry were truly co-laborers. The work of both writers narrates the problem of Man in Mass Society, which Merton describes in Marxist terms as a problem of alienation. Man is alienated from his work. He works for others and does not get or even see the product of his labor. Instead of revolution, Merton gives this solution:

Work that is productive, properly organized, and remains in contact with nature, work that is truly physical and manual outdoor work, work that is properly managed and well done, work that is managed and taught on a human and monastic level, and not carried out like factory-type drudgery or office routines— such work can do much to help the young monk find his identity and grow in Christ, by teaching him to accept himself, work in harmony with others, and feel himself fully part of a world made by a loving father in which his own work has a redemptive and sanctifying quality because it is united with the labor and sacrifice of the Incarnate Son of God.

Though seldom invoking dogma in this way, you can find this kind of thing on almost every page of Berry. In one instance, in his book on William Carlos Williams, he criticizes those “numerous people to whom ‘the Word was made flesh’ was no more than an idea.” Recall also how anti-platonic the Merton of Seven Story Mountain is. This resistance to abstraction is partly what led Merton to Zen in the first place. We live abstracted lives. We flip a switch and we have light. We open a package and we have dinner. We cast our images onto the internet. We look at other people’s bodies through a screen. Think of how companies like Zoom have abstracted and commodified basic human interaction. In his hermitage, Merton felt he was encountering real life and was therefore capable of giving himself to God more fully. This privileging of the concrete world of disembodied ideas, for both Merton and Berry, is rooted in the incarnation. Because the word has been made flesh “there are no unsacred places.” Berry illustrates this point well in “A Native Hill” from 1969: “A path is little more than a habit that comes with knowledge of a place.” A path is the incarnation of a people’s idea of the place, while the road is almost pure abstraction whose “tendency is to translate place into space in order to traverse it with the least effort.” Elsewhere, Berry describes his commute from Lexington, where he taught, to the long-legged house as a journey from the abstract into the concrete:

It was always a journey from the sound of public voices to the sound of a private quiet voice rising falteringly out of the roots of my mind, that I listened carefully in the silence to hear. It was a journey from the abstract collective life of the university and the city into the intimate country of my own life. It is only a country that is well known, full of familiar names and places, full of life that is always changing, that the mind goes free of abstractions, and renews itself in the presence of the creation, that so persistently eludes human comprehension and human law.

Merton describes the hermitage in similar terms, saying that the hermit’s life “should bear witness to the fact that certain basic claims about solitude and peace are in fact true. And in doing this, it will restore people’s confidence, first in their own humanity and beyond that in the grace of God.”

Merton makes this point, that grace is not opposed to nature, in an attempt to redefine the monk’s position toward the world. For him, the point of the monastic life is not a rigid turning away from ‘the world,’ an escape from the flesh but an opportunity to get more in touch with what it means to be fully human in a world that dehumanizes us. The monk works with his body and seeks silence and solitude so that “his mind and heart can relax and expand . . . there too he can hear the word of God and meditate on it more quietly, without strain, without forcing himself, without being carried away in useless speculations.” Silence, apart from farming, is Berry’s other major preoccupation. Think of how Burley keeps reminding Nathan that “It doesn’t pay to talk too much about your business” in Nathan Coulter, how the novel’s would-be climax of the huge catfish is spoiled for Burley by too much chatter, and how, by the end, Nathan begins a long silence that will last the rest of his life. Encouraging the reader to get rid of the television set, Berry says “the ensuing silence is an invitation to our homes, to our own places and lives, to come into being.” On finding one’s own place Merton writes “this implies a kind of mysterious awakening to the fact that where we actually are is where we belong.” This means that I belong at this desk, in this room, on this acre of woods at the edge of a much larger forest, and not anywhere the computer that is on my desk can take me. Silence for Merton, as a monk, is of course connected to prayer. So it seems with Berry:

Accept what comes from silence.

Make the best you can of it.

Of what little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

5 comments

Nicolas Salter

“Not a quiet place but a place of quiet.” Thank you for rescuing this adage.

Jacob Taylor

Thank you for telling us the story of Berry and Merton connecting. I didn’t know, and now I do!

Gerrit

Thanks for a wonderful article.

Nancy Baillie Strong

Thank you for this article, much appreciated.

Russell Arben Fox

This is a beautiful reflection Dan, one that I much appreciate as I nurse a headache in the silence of my home this early morning. I would describe Berry as even closer to certain Marxist insights than you, but you’re certainly correct that he’s never been more poetic than dogmatic, and better for it. Putting that passage from “A Native Hill” in dialogue with Merton’s description of his hermitage is kind of genius; it’s a comparison–and a bit of a rebuke–that will stay with me all day, I suspect. Thank you.

Comments are closed.