Chandler, OK. It was at one time a nearly universal assumption that a great people, state, or nation will inevitably produce a great poet, a Homer of their own. The Romans looked back at the accomplishments of the Greeks and asked, “Who is our Homer?” Enter Virgil. Medieval Christendom responded thereafter with Dante and Renaissance England with Milton. So, who is the American Homer?

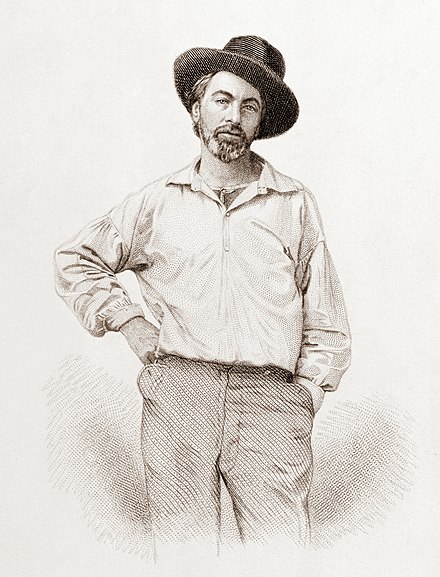

One frequent answer in the past has been Walt Whitman. Styling himself as an “everyman” kind of American, Whitman pioneered free verse, thus seeming to liberate himself from the restraints of the poetic tradition he inherited. He championed the common man and celebrated the vast and various landscape of a relatively young America. He exuded American individualism and earthy roughness. He wrote two great elegies for President Lincoln. In short, he made a direct bid to become America’s poet, and America loved him for it, at first despite and eventually because of his scandalous sexual predilections. School children memorized “O Captain, My Captain.” There are high schools named after him. His verse has shown up in popular movies such as Dead Poets Society, and his magnum opus Leaves of Grass featured in a pivotal moment on Breaking Bad. America has loved Whitman as much or more than any poet.

I am, however, falling out of love with Whitman.

Once, I was all in on the poet. I still have a copy of Leaves of Grass that my parents inscribed to me for Christmas when I was sixteen. It was my constant companion through high school and college. I read it in class when there was little else to do in my rural high school. When home from college in the summers, I carried the book into the woods behind my house and sat reading for hours while, though it pains me to admit it, smoking a corncob pipe. I recited Whitman at open-mic nights, and wrote my own sprawling verse in imitation of his. I read from the poet’s “Song of the Open Road” at my father’s funeral. I was once enchanted with the work and the persona of Walt Whitman, but now I am becoming decidedly disenchanted.

In large part, it is teaching Whitman’s work that has spoiled him for me. Not simply because teaching a work well obliges one to reread it year after year. I was constantly reading Whitman already, and returning to other authors, Dante for instance, has only strengthened my love for them. No, rather it was precisely because I was charged with explicating Whitman to young people that I began to see his luster fade. He seemed, frankly, to be telling the undergraduates all the wrong things. I’m not talking about sex. Or at least I’m not talking just about sex. I’m talking about his tendency to espouse and celebrate things that just aren’t so.

Teaching at a small liberal arts college, I have to put a lot of time and work into convincing my students that books, particularly old books, are well worth reading. Whitman tends to tell them otherwise. In “Song of Myself,” the central poem of Leaves of Grass, he says in one long and flowing line, “You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in books.” This line sounds refreshingly modern and boldly confident, but looking through the eyes of the dead is precisely what I spend a good deal of time trying to convince my students to do. I want my students to understand that if they rely upon only the intellectual fashions of the moment or only their own intuitions, they are sure to miss out on much that is true and good and beautiful. But seeing through the eyes of the dead takes work. It takes hours of reading. It might even require learning a dead language or two. Whitman offers students a seductively easy answer in the face of that hard work. You already know all you need to know, he tells them. “All truths wait in all things,” he says in “Song of Myself.” So, you know, why try too hard?

This attitude leads Whitman to a pronounced anti-intellectualism, as in the famous poem “When I Heard the Learned Astronomer,” a lovely poem in its way but one that encourages the laziest habits of mind. The poem begins with the poet sitting in a lecture hall listening to an explanation of the astronomer’s “charts and diagrams.” Soon, however, like an undergrad grudgingly fulfilling his science gen-ed requirement, the poet grows unbearably bored. Eventually he gets up—seemingly while the lecturer is still explaining the workings of the heavens—and wanders out into “the mystical moist night-air” where he implies he learns much more than those inside the lecture hall simply by looking “up in perfect silence at the stars.” I would and in fact do ardently implore my students to spend as much time as possible gazing in wonder at the night sky. To do so inevitably enriches own’s soul. It helps instill a sense of wonder and a sense of proportion. But I would never juxtapose such enrichment to the other kind of enrichment that comes from actual knowledge of astronomy. Galileo famously said that “mathematics is the language in which God writes the universe.” Is there not an experience of wonder to be found in learning to read that language as well as in simply gazing at the sky? Whitman gives easy permission to dismiss so much that is worth working for. To love creation, you don’t need anything that is not already inside you, he says. That’s not enchantment; that’s just egotism in mystical dress.

Once I began considering his dismissive attitude about the wisdom of the ages and the spirit of inquiry, the luster began to fade from Whitman’s innovations in “free verse” as well. His poetry has an undeniable energy which still draws me to it, but that energy is, to a great extent, created by burning down the traditions of meter and form that had been inseparable from the creation of verse in English since at least Chaucer. There’s a jolt of energy in that destructive act, but what others manage to do within the limits of tradition now seems more impressive to me than what can be done simply by ignoring all constraint. As the Irish poet Paul Muldoon once said, “Form is a straightjacket like a straightjacket is a straightjacket to Houdini.” For all its energy, Whitman’s verse sometimes does seem like, to borrow Robert Frost’s quip about free verse, “playing tennis with the net down.”

Whitman’s take on religion is even worse than his take on verse. He seems to be the voice of much that is silly and self-serving in American spirituality, an ancestor to every self-satisfied social media profile proclaiming its owner to be “spiritual but not religious.” Whitman, of course, found inspiration for his hollow, tautological spiritually among the American transcendentalist, those great forerunners of vaguely comforting feelings about eschatology and requests for “good vibrations” and “positive thoughts.” Whitman’s contribution is to give the thought of Emerson an easy mass appeal. Whitman is certainly no mere materialist, but the spiritual assertions of “Song of Myself” don’t provide a very clear sense of what he does believe: “I am not an earth nor an adjunct of an earth, / I am the mate and companion of people, all just as immortal and fathomless as myself, / (They do not know how immortal, but I know.)” Such a statement lacks the whole comfort of traditional faith but also the courage of overt disbelief. If one can’t have the confident joy of a Dante, one could at least have the frank despair of a Samuel Beckett. Whitman offers a spirituality that asks nothing of us but to be us. “Why should I pray? why should I venerate and be ceremonious?” he asks in “Song of Myself.” There is neither rigor nor sanctification nor awe nor sincere hope in such an untroubling spirituality. But in its ease such a “faith” has mass appeal. It asks you to bow before nothing that is not already you.

And that brings me to my real contention with Whitman: both Whitman’s antagonism to tradition and his easy spiritually are rooted in the impulse to make the self the locus of all meaning. “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” begins “Song of Myself,” a mantra suitable for the age of Instagram. Later in the poem he proclaims, “One world is aware and by far the largest to me, and that is myself[.]” This sense of a self so limitless it subsumes all other things under it or absorbs all other things into it is a major tributary of the great river of insanities in American life today, from the right’s inability to dismiss bizarre conspiracy theories as outside the pale of probability to the left’s obsession with dismissing the biological basis of gender. In Whitman we find eloquent and forceful expression of the unlimited sense of self that drives us to abandon the communities that have nourished us, to shutter the institutions that have formed us, and to shake off the marriages to which we have committed. Whitman speaks for much of America in his insistence that the limitless self is beyond fact and fiction as surely as Nietzsche’s ubermensch is beyond good and evil. Famously the poet proclaims, “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself. / (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” When one is limitless, one need not bother with consistency, integrity, or reason. This is the spirit that presides over our media, social and anti-social alike. This proclamation of the limitless self is a message my students are steeped in day and night. They hear it from advertisers who see the limitless self as a limitless consumer, as well as from the empowering messages of podcasters and politicians. Sadly, those who insist there is no greatness other than your own like to think that they are inviting you out from the airless marble tombs of thought into a robust life of fresh air and sunshine in the open fields of democracy. They are, rather, calling you down from the clean air of the mountain tops to breathe the stuffy air of the closed-off self.

One good definition of an epic poem is “the story of all things,” a phrase Samuel Barrow applied to Milton’s Paradise Lost but which could also be said, from the perspective of the culture which produced it, of the Iliad, the Aeneid, and the Divine Comedy. Leaves of Grass is also meant to offer “the story of all things,” but, despite its laudable attention to all the varied landscapes and human occupations of young America, in Whitman’s poetry the self is all things. Everything is subsumed under the glorious identity of the autonomous individual. My students are constantly told this story. It is in the air all around them. I want the books we read to offer them a different and a better and a truer story, one which gives them an opportunity to be a part of something bigger than all of us. I want great books to call them to an encounter with the giveness of the world rather than just with an infinitely malleable and all-consuming self at the center of all things.

I’m not “canceling” Whitman. I will continue to teach his work and to pick up Leaves of Grass from time to time simply for the pleasure of reading it. I will continue to teach Whitman because, despite his own anti-traditionalism, he has come to occupy an important place in the American literary tradition. He also offers an interesting entryway into discussion of American optimism and individualism, a useful window on social and intellectual history. More importantly, I will continue to teach and read Whitman because there is much that is beautiful in his verse. “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed” achieves an almost classical dignity and solemnity at times in its lament for Lincoln. Throughout “Song of Myself” and in other poems such as “I Hear America Singing,” “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” and “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking,” there are many finely envisioned images, pictures of rugged honest labor, of everyday American life, and of natural beauty. It is sometimes worth wading through Whitman’s self-importance and eyeroll-inducing enthusiasms to see the world through his eyes, which are now too “the eyes of the dead.”

No, I’m not canceling Whitman. But my own enthusiasm for his poetry is waning. The poet whose daring versification and daring lifestyle were once seen as the epitome of counter-culture has come to seem to me all too mainstream, the very voice of an age of superficial egotism.

5 comments

PFSchaffner

For ‘giveness’ (I think) read ‘givenness’; the latter denotes the brute fact of the world as something given; the former is an Old English word meaning ‘grace,’ or a Middle English word shortened from ‘forgiveness,’ in either case not current.

Adam Smith

Well this is very interesting. Is our situation more “too much Whitman” or “too little Whitman”?

I do agree with Michael that different things can be necessary at different times in history. I also agree that we now live in a Bio-Political Hellscape. What then is the role of Whitmanesque “autonomy talk” – is it what we need now to resist this hellscape, or is it, perversely, one of the cultural factors that leads us into it (a possibility I would be eager to explore)?

I recently finished reading (and teaching) Matthew Crawford’s The World Beyond Your Head, in which he sharply distinguishes “autonomy,” as the freedom to define yourself at a whim without having to struggle with and against the world around you, from “agency,” as the freedom you achieve precisely via that struggle with things that resist your will. Maybe what we get in Whitman is a blurring of that distinction, such that he can feed either tendency. I would argue that to the extent any poet has fed any cultural tendency, he’s been used mainly to promote autonomy, or interpreted by people who already believe freedom is autonomy rather than agency (see, for example, the Levi’s jeans add with a Whitman poem as voiceover, praising non-conformity, which you apparently achieve by buying Levi’s brand jeans). But I am certainly feeling desperate for Whitman’s brand of a full-throated, romantic embrace of passionate individuality which is not so protective of its “autonomy” that it cannot countenance anything outside of the head that puts that autonomy at any risk — an individuality that would hate and fight this cult of safety, without losing its sense of good cheer.

Michael Sauter

Benjamin– Thanks for this, as the timing is good, even though I myself, might have penned an essay called “Why, As the Bio-political Hellscape-Making Machine Enters its Consolidation Phase, Whitman Is Now More than Necessary than Ever: Read Him Today!”

Unlike you, I have not read Whitman for all that long, but he is, in fact, the poet who has spoken to me most this past year with all of its strange goings-on. Sane people can disagree, but I find him to be a writer who mucks up the gears of the Dark Scientific Mills which are generating the Techno-Fascism descending upon us in and through all things “warp speed”. And, at the same time, he empowers precisely those energies of the soul that would help us resist forces of alienation and fatalism and hopelessness.

So impressed, in fact, that a few weeks ago I went looking for other authors I admire and wanted to see what they saw in Whitman. I wasn’t surprised to see that John Cowper Powys was a fan and that Whitman, who’s religious sensibilities were, admittedly and delightfully all over the map, zeroed in on “the Lord Christ” (the new, the hoped-for, etc.), with an acuity that would make most professed Christians look clueless:

“He [Whitman] seems to hold open by main, gigantic force that door of hope which Fate and God and Man and the Laws of Nature are all endeavoring to close! And he holds it open! And it is open still. It is for this reason—let the profane hold their peace!—that I do not hesitate to understand very clearly why he addresses a certain poem to the Lord Christ! Whether it be true or not that the Pure in Heart see God, it is certainly true that they have a power of saving us from God’s Law of Cause and Effect!….

…Deny it, who may or will. There will always gather round him—as he predicted—out of City-Tenements and Artist-Studios and Factory-Shops and Ware-Houses and Bordelloes—aye! and, it may be, out of the purlieus of Palaces themselves—a strange, mad, heart-broken company of life-defeated derelicts, who come, not for Cosmic Emotion or Democracy or Anarchy or Amorousness, or even “Comradeship,” but for that touch, that whisper, that word, that hand outstretched in the darkness, which makes them know—against reason and argument and all evidence—that they may hope still—for the Impossible is true!”

As Owen Barfield saw, the “one needful thing” at any given time in history has to be seen as set against the peculiar besetting sin of the age. There are a lot of forms of egoistic self-absorption that are truly, in the best sense, American (and come from the land), as well as not technically narcissistic, (a whole conversation that go so confused these past 4 years), and which might be the needed Yin to the dehumanizing Yang of these hypermodern, bee-hive constructing times. Whitman is necessary.

Rob G

I’m not sure Whitman is helpful given that the culture has been screaming “Have it your way!” for 50 years. Applying Whitman to the problem seems a bit too close to homeopathy. It’s a shame that the U.S. never really produced an American Wordsworth.

Adam Smith

Just last night I randomly picked up my copy of Leaves of Grass, and as I paged through it, looking to loaf and invite my soul, I had precisely the same thought that you express so beautifully in this piece. Everyone is Whitman now, and it’s not great.

Comments are closed.