Charlotesville, VA. About a month ago the following exchange broke out across the street as a few men and I did jumping jacks at six in the morning in front the Rotunda at the University of Virginia:

“Move your f****** car!”

“You have plenty of room to get out.”

“F*** you b*****! You wanna go?!”

“It’s five-thirty in the f****** morning. What is your problem?”

A couple of guys stopped their calisthenics and looked over. “Is that S—-? I think we should go help him out.” We jogged down to the street where we saw a man shouting into the car window of a recently arrived workout participant. The incensed man climbed back into his Virginia battle flag-bedecked pickup truck, peeled out of the spot where he had parallel parked, and roared down University Avenue. I guess he did have sufficient room to maneuver out of his space after all.

Meanwhile a friend I had invited to join our workout that morning crossed the street to meet up with us after witnessing the near-altercation. I promised him our workouts don’t normally start like that. “I thought we were gonna do a boxing workout this morning,” another man said.

It’s probably not a stretch to identify the hostile exchange we witnessed that morning as a paradigm of “toxic masculinity.” The raised pickup, the confederate flag, the rage at something as innocuous as Prius parallel parking in front of him, all would qualify as marks of something that causes people in polite, liberal circles to cluck their tongues, shake their heads, and let out a sigh in response to a phenomenon characterized by aggression, competition, and bravado.

It seemed providential that, later that day, this essay by Mary Harrington at UnHerd popped up in my RSS reader. Harrington interrogates the current assumption of toxic masculine behavior as being solely the product of cultural, economic, and political conditioning, rather than biology. She argues that efforts to “train boys out of being cock-ish”, which are “fine, provided you believe human nature to be completely malleable,” might in fact be having an undesired effect, causing young men to double down on the most destructive and, er, toxic expressions of attributes that progressive culture has pathologized. She presents phenomena such as internet subcultures that revere machismo, radicalized Western fighters joining ISIS, and right-wingers going to participate in conflicts in the Ukraine, as evidence that well-intentioned efforts to mitigate men’s aggressive and pugnacious impulses might, at best, be falling short. Reflecting on the story of Craig Lang, an American who’s “wanted for murder in the USA but feted as a hero in Ukraine,” she concludes,

Lang is relatively unusual in seeking out combat. But the underbelly of the internet is full of men violently hostile to the norms of a “feminist” mainstream that deplores the things they value, and who daydream increasingly vividly about the search for glory. Perhaps they will confine this to the realm of fantasy forever. But perhaps they won’t.

None of this is to offer an unqualified endorsement of these traits, which have many downsides. But wouldn’t we be better-advised to seek constructive roles for the men who possess them, rather than trying to “educate” (in other words shame) “toxic masculinity” out of existence. Especially if the alternative is a growing subculture of men who have gone beyond daydreaming online about “Vikings”, to actively seeking to recreate their violent, restless and hypermasculine world in the 21st century.

…for men whose personalities tend toward aggression, protectiveness, competition and stoicism, what honourable roles are left? We’d be foolish to shrug our shoulders as such men lose hope of being valued as protectors, and start looking for glory as wolves.

I’m agnostic as to the nature/nurture ratio in the development of aggressive male behavior. As someone resistant to reductionism, I expect that both play a role, but if the behavior of the one-eyed male kitten my wife and I adopted roughly six months ago is any indication, I, along with Harrington, suspect biology plays a bigger role across species than many would like to admit. He is quintessentially boyish—as I write this, he has used my desk, shoulders, head, bookshelf, and audio system as a jungle gym.

Wherever you land on the question of nature and nurture though, Harrington’s question of what honorable roles remain for “men whose personalities tend toward aggression, protectiveness, competition and stoicism” still persists. But I think an even more fundamental question is pressing even for men whose personalities don’t embody those traits—what is an honorable expression of masculinity in the first place?

Fitness, fellowship, and faith, attributes that provide the name for F3, a grassroots, peer-led organization that I work out with, offer possible answers. In January 2021, I decided to try working out with them at the suggestion of my wife, whose coworker introduced me to the group. In the depths of a seemingly interminable pandemic winter and its attendant restrictions, I can confidently say that all three of F3’s namesakes were languishing in my life. My gym attendance was middling at best. Our good group of friends prioritized spending time together, but plans to hang out were regularly disrupted by voluntary quarantines due to potential virus exposures. Our church’s doors were indefinitely closed per the orders of our diocese. I was deeply depressed, addicted to the news cycle, and stuck in my head. I urgently needed to be dragged outside of my brain and into my body, to be turned away from the screen and towards the world.

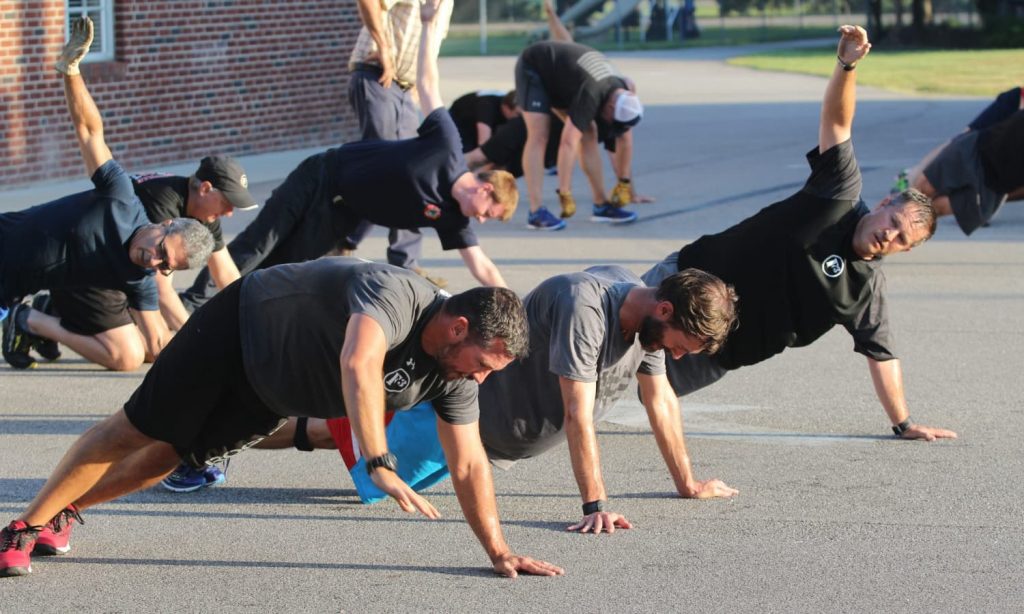

The first time I came to a workout, we “warmed up” with burpees, pushups, and other exercises in front of the UVA Rotunda. The following forty-five minutes consisted of calisthenics and running, including doing 100 burpees over the course of the workout (yours truly did not complete the hundred burpees). At one point during a jog from the Rotunda to the pull-up bars at the ROTC playground, my legs gave out and I began to walk. One of the men ran back and encouraged me to jog at a reasonable pace. “It won’t get easier, but you will get stronger,” he said to me. I later learned that a common refrain among F3 members is “leave no man behind, but leave no man where you found him.” The workout closed with a “Circle of Trust,” where the workout’s leader shares something meaningful—the “faith” aspect—with everyone in attendance. Everyone then gives his name, age, and F3 name (a nickname granted by the group) in succession, with everyone cheering a given person’s F3 name in response. I was instructed to give “FNG” (friendly new guy) as my F3 name. After that, I stood in the middle of a circle, and shared various facts about myself—what I do for work or fun, my first or favorite concert, any embarrassing facts—and was given the name “Blowout,” in honor of a, ahem, bowel movement, that occurred at my christening.

F3 has five tenets: it’s always free; it’s open to all men; it’s always outside, rain or shine, hot or cold; it’s always peer led (“not by a professional, so modify workouts as needed”); and it always ends in a circle of trust. Although based around working out (fitness), F3’s greater vision is to help men build relationships with one another (fellowship), and orient them toward something outside of themselves (faith). Although a number of the participants are Christians, F3 does not exist to proselytize—the faith aspect is deliberately left ambiguous so as to remain inclusive of men from all walks of life. I have no idea what the religious makeup is for my local chapter, but more than a few of the guys I work out with have no religious affiliation at all. Ultimately, F3 is meant to counteract the especially male phenomenon of what Tony Soprano calls the “sad clown”—“laughing on the outside, crying on the inside.” In the midst of a culture that encourages men to either act with self-aggrandizing machismo or pathologizes any expressions of stereotypically masculine behavior, F3 builds a culture of men whose purpose is to serve their families and communities while building deep connections with one another.

Coming across Harrington’s essay that morning was fortuitous. During much of the past year, her musings would have been just another segment of information for me to bemoan, another piece of ammunition in my arsenal of despondency and bitterness. But that morning I was flooded with endorphins after doing lunges and burpees across the Rotunda lawn. And I had spent the last few months with men in the pre-dawn gloom learning that true masculinity is about countering our instincts of anxiety, despair, and resentment with courage, hope, and grace. Such a perspective was summarized perfectly by one of the guys as we drank some post-workout coffee on the sidewalk in front of St. Paul’s Memorial Church and reflected on the rage of the man we encountered earlier that morning: “You know, we shoulda said to that guy, ‘Man, you need to come work out.’”

6 comments

Scot Martin

As stereotypes go, I find myself on the outs of most American male interests (the outdoors being a large exception). I hate war and the near idolatry we have of our military and its “heroes,” yet I enjoy the Iliad and get a particular thrill out of burning things and killing invasive plants (my chainsaw is one of my three favorite tools).

I appreciate your examining the tension that we men live with in this piece.

Adam williams

Well said! You hit a number of thoughts I have not been able to express but have had.

Thanks

Turtle

Lee Howell

F3 fills the missing link for many men. Aye! See you in the gloom sometime.

F3 Charlie Brown

David Naas

More groups like this needed, alas.

It used to be, before society “moved on”, that aggressive young men chock full of those teenage hormones which get a fella in one kind of trouble or another, would be nurtured and nursed by a friendly, kindly Drill Sergeant as the young draftee went through basic/boot camp. Pugil sticks have a wonderful way of knocking the XXXX and vinegar out of a punk and turning him into something relatively disciplined, if not fully civilized. But we don’t do that anymore.

As noted above, idealists presume the total malleability of humans, when the truth is we are not malleable at all, merely divertable from one course to another.

ceej la weej

“another piece of ammunition in my arsenal of despondency and bitterness.” beautiful work, Blowout.

dave

Well done, thanks. And yeah, Bodos will do it. Worth working off.

Comments are closed.