Princeton, NJ. Not much has changed about her alma mater’s orientation programming since Christine Emba attended as a freshman over a decade ago. “We file into a dark auditorium to watch a meant-to-be-educational skit that dramatize[s] a typical weekend night out, complete with budding romances, bad jokes…and then—startlingly—an alcohol enabled sexual assault.” The one glaring difference between the 2006 play and the 2018 production she attended on assignment was the administrator’s post–show discussion about consent. Yet this minor addition isn’t really what’s needed in our public conversations about sex. Emba had heard plenty of stories over brunch with friends, at the office, and at parties that suggest that the absence of consent is nowhere near the foremost problem afflicting contemporary sexual culture.

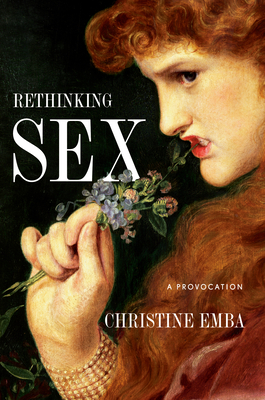

At a time when casual sex is culturally accepted and often glorified, more young people – and especially women – are waking up to the “gulf” between hoped-for relationships and the ones which our “social climate puts on offer.” These chronicles of disappointment, both fictive and real, reveal the unhappy ways in which people discover that they have used and been used for a night of pleasure, for some sense of security against the slow creep of loneliness. In Rethinking Sex, Emba maintains that consent “is a floor, not a ceiling” and challenges the mainstream assumption that this ethical standard suffices to remedy every instance of sexual dissatisfaction and misbehavior. Armed with probing questions about what constitutes “good sex” and abundant evidence of our failed sexual norms, Emba sets out to raise her reader’s hopes and expectations for deeper, more fulfilling relationships.

Emba’s journalistic style, woven through with interviews, pop culture references, and personal experience, fleshes out the story of how we got here and why. Her interviewees capture the reticence of Millennials to make moral judgments about what is and is not morally permissible behavior. Their remarks reveal the dawning of a new realization on Gen Z—that a thicker moral conception is needed to guide our actions and dispositions toward each other. Emba herself has experienced everything from “purity ring” evangelicalism and hookup culture to a recommitment to and later abandonment of abstinence until marriage. Sitting astride the drastically divergent worlds of conservative Christianity and secularism, Emba shows that sexual negotiations—and negotiation between the sexes—are as ancient as they are new.

Promising to help her reader rethink “the way we approach our bodies, our relationships, and ourselves, and the world around us,” Emba responds empathetically to movements like #MeToo, which revealed society’s ugly underbelly of apathy, abuse, and objectification. However, she remains skeptical about the sex-positive stance taken up by affirmative consent proponents who devise slogans such as “sex is like a sandwich,” or “sex is like a cup of tea”; these bromides distract us from our moral responsibility toward ourselves and our partners.

She also questions the tendency of the loudest #MeToo voices to meet non-criminal cases of sexual misconduct with a legalistic standard of consent rather than a moral judgment. The push to define rape as an “absence of affirmative consent from the alleged victim rather than by the presence of non-consent” sidesteps an uncomfortable truth about ourselves. How many of us are willing to demand restitution through imprisonment instead of naming the moral offenses committed—arrogance, vanity, vulgarity, greed, licentiousness—of which we ourselves could be guilty to varying degrees? “Framing sex as a categorical imperative…is what allows predators to justify sexual harassment and assault as what they need to do in order to get off.” The refusal to make moral judgments indicates not necessarily a lack of desire to hold others accountable as much as the fear that in doing so, we might restrict our own will and pleasure. Thus when women wonder, “I didn’t really want it, but I did it; it wasn’t rape, but it feels bad,” they need a recovery of moral vision, not legal proceedings.

According to Emba, the consent standard has so permeated our discourse that we denounce substantive moral arguments in favor of “a discourse around individual goods and rights,” one which emphasizes personal pleasure over personal responsibility. She argues this resistance results from a narrowly concerned individualism, where “any claims about how we should relate to each other takes on a tang of moralism and religiosity and should be negotiated in the private sphere.” But as our relationships possess both a private and public dimension, Emba rightly contends that what we desire and pursue in those relationships really matters to those around us. She warns that our hesitation to condemn objectification and degradation where we see it can make our culture “worse, for ourselves and those around us.”

Emba attributes this tendency of ours—a tendency to treat others as means to our own pleasurable ends—to a radically individualistic capitalism. In her review for the New York Times, Michelle Goldberg notes that Rethinking Sex captures the phenomenon of “sex negativity,” an incipient revolt against libertine capitalism’s twin fruits of commodification and atomization. For Emba, sex positivity itself is the outgrowth of a market-logic of individual choice that ignores the reality of our mutual dependency, of our human need for relationship and communion with others. Her conclusion, as some on the left have pointed out, is rather traditional: non-judgment, “combined with an easily fudged definition of consent, means that more people will be pushed into acts or experiences that they aren’t comfortable with.” And when enough people are pushed into a corner, they will push back against the steady march of progress and liberation.

Goldberg critiques Emba for moralizing about other people’s sexual preferences, but insofar as Rethinking Sex is intended to stoke moral sensitivities, its greatest weakness is that it does not articulate the full extent of what our mutual dependency should mean for our actions. The most curious omission concerns reproduction, only mentioned once as “a fundamental urge, one with the unique potential to create a new human life and one that…creates extreme vulnerability [for women].” In other words, while Emba lights the way to a recovery of moral sensitivity in the realm of sex, what she doesn’t explore is a fact so important to our moral thinking about sex that its omission is rather shocking: sex inherently includes procreative ends. In light of Emba’s clarion call to submit our sexual desires and acts to moral scrutiny, this absence bears a closer look.

What Emba most successfully conveys throughout the entirety of her brief book is an awareness that we are never “our own.” This is certainly right, but she does not go far enough in revealing just how radical this interdependence is, and why it warrants placing sex back within the context of marriage and family-building. While Rethinking Sex speaks to an audience fed up with sexual disappointment, it omits family and marriage as forms of belonging and responsibility that stem from our sexuality. A properly radical rethinking of sex would narrate this act as a physical and spiritual union between two people in the presence of a possible third, despite the hypnosis provided by widely available contraception.

Emba could have expounded on this dimension in terms of the teleological approach of Aristotle and Aquinas, whom she mentions in the book’s second to last chapter. Borrowing the famous words of Aristotle later echoed in the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, she proposes that we should “will the good of the other” to avoid instrumentalizing ourselves and others. She rightly observes that we should care enough about the other person to consider whether our actions and the consequences of our actions might affect them for good or for ill. Emba writes that sex is spiritual, that it ties the people who participate in it together in a mysterious way. But she neglects to acknowledge that in truth, the most radical form of “willing the good of the other” according to the demands of a comprehensive sexual ethic would mean exercising the virtue of chastity in the fullest sense—physical abstention from the act of sex until the sealing of a couple’s unitive intention in sacramental marriage. Being relational creatures, we are in a precondition of “entanglement,” as Leah Libresco Sargeant observes. Our bodies are less bounded than we might imagine—so much so that we still can’t fully comprehend the mystery of conception in which a new person comes into being.

At root, Emba’s book is a personalist call to honor the presence of others as real persons for whom we are responsible, which makes the omission of procreation all the more curious. We are not simply a bundle of pleasures; we are gifted with human dignity from the moment of our conception, inextricably caught up in our parents’ loving embrace. Emba’s focus on sex as union finally fails to release her readers from the view of sex as pleasure, even if she spends pages illustrating why one should morally reject that view.

One further note: given the author’s concern for upholding the dignity of the person and finding joy through moral deliberation, it is strange to discover instances of unnecessarily frank description and vulgar slang which undermine the author’s argument for restoring dignity and restraint to our sexual culture. Though forgivable in primary sources, such language does a disservice to the author’s pressing message. In examining unhealthy sexual culture, she would have done well to leave some things to the imagination.

Taken altogether, Emba’s reverence for the person comes across in her ideas and the care she has taken to write and publish such a challenging, detailed book. However, while so much of her contribution illuminates the dark corners of today’s sexual culture, a reader may come away with only a partial vision of our interdependence with, and thus our responsibility toward, one another. The absence of concepts such as traditional marriage, chastity, family, and faith are understandable given Emba’s desired readership, but without these categories, it’s impossible to narrate sexuality as a powerful enactment of loving, interdependent union. Emba is right that consent is an inadequate form to protect and honor this union. Our culture remains in desperate need of religious and cultural resources to regain a moral vision adequate to this profound mystery.

6 comments

Rob G

“Framing sex as a categorical imperative…is what allows predators to justify sexual harassment and assault as what they need to do in order to get off.”

I think the point is that if you see sexual desire as the same sort of imperative as the need for food or shelter, then it becomes much easier to justify sexual predation. No one blames a starving man for stealing a loaf of bread, right?

Martin

This is a good review, but it starts off slow and somewhat confusing, probably because Julia strings together various book excerpts with a minimum of words spent smoothing the transitions.

I honestly don’t understand this quote:

“Framing sex as a categorical imperative…is what allows predators to justify sexual harassment and assault as what they need to do in order to get off.”

Wikipedia’s page on “categorical imperative” explains Kant as opposing such justification:

“a utilitarian says that murder is wrong because it does not maximize good for those involved, but this is irrelevant to people who are concerned only with maximizing the positive outcome for themselves.”

Anyway, my main disappointment with this review is that it frames sex-positive in such a poor light, without comparing it to the sex-negative dogma that now disdains reproduction entirely: birth strikers, women and men who see sex only as a form of oppression, babies as parasites on “my” body, etc.

Celebrating femininity and womanhood should dovetail with respect for motherhood, as Julia says. In that light, I see sex-positive advocates as inherently favoring life but simply lacking direction.

Brian

This feels like a discussion of planetary dynamics where “gravity” is a forbidden subject.

I mean, come on: “Their remarks reveal the dawning of a new realization on Gen Z—that a thicker moral conception is needed to guide our actions and dispositions toward each other.”

Gee, ya think?

Your final paragraph is a gentle nudge when what’s really needed is a bullhorn.

I always wonder why the “sex-positive” (ugh what a stupid term) utilitarian argument is never made–you want to have lots of sex with someone who is motivated to make it good for you? Get married!

Well, no, I don’t wonder, not really. Because for these people “sex-positive” is a means to the “destroy marriage” end, not an end in and of itself…

Rob G

There is absolutely a sense in which this shouldn’t be news, but one can’t hold Gen Z (and Millennials, for that matter) entirely responsible for missing it, given what the culture has educated them into. After all, they weren’t the ones who invented the notion that “a marriage license is just a piece of paper,” while simultaneously advocating that it was the most important thing in the universe that gays be able to have one. Is it any wonder they’re confused?

I once asked a very intelligent college-grad millennial if it were not possible that the same system she saw as screwing over blacks and other minorities was also doing the same to poor whites and the “white working class.” She said that she had never thought of it that way before. One would have thought that such a thing was obvious, but it’s not obvious if it’s never been presented to you as an alternative. (I told her to read Chris Arnade.)

I tell that story to illustrate the fact that there are things that these younger people simply do not get, not because they’re stupid or immoral, but because they’ve never really been asked to consider them (which is of course part of the plan). The works and pomps of modernity have been presented to them as givens, with little or no consideration of the alternatives. And in the case of “traditional” understandings, they’ve often been demonized or ridiculed when they weren’t being ignored.

Brian

“one can’t hold Gen Z (and Millennials, for that matter) entirely responsible for missing it, given what the culture has educated them into”

I don’t disagree.

It seems to me that this book is an attempt by the author to speak to the Ivy League / NY Times set, so she can’t make a religious case, because that demographic has a visceral reaction to anything like that. More power to her for trying, I guess, but it’s hopeless:

“Goldberg critiques Emba for moralizing about other people’s sexual preference”

Rich and famous woman says you can’t judge other people’s sexual behavior. Rich and famous woman is also married with children, in case you were wondering.

Rob G

I will grant that it’s tough to be woke and critical at the same time. How do you know where to draw the lines?

Comments are closed.