“We seem to be born homesick, and that homesickness is meant to lead us into a life of pilgrimage.”

Walker Percy

Black Mountain, NC. Where are you going? At its core, an education seeks to answer that question. Where are you going and where do you want to go? Every educational philosophy has an inherent destination attached to it—a certain ideal student. As such, every education encourages a certain pilgrimage.

But the question of where we are going is also dictated by what story we tell ourselves. One of those quotations that haunts me—that keeps churning in my mind—is from Alasdair MacIntyre. He wrote, “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’” The question of action is tied to the question of story. How we pursue an education has everything to do with how we imagine the world.

When I was growing up, imagination seemed like a silly thing. The implied connotation of imagination was childish, fake, or immature. I wanted to be mature, and being mature meant being reasonable. I wanted arguments, rationales, and deep thought. Imagination seemed trivial and emotional. Stories and narratives were for kids.

However, I’ve come to see that stories are not escapes from otherwise “real” life; rather, stories direct our life like a compass. They set a navigational bearing. Every education carries different stories—stories of what success means, about who human persons are, about what we are made for. The problem with many modern educational theories is that they live by the wrong story, so of course the pilgrimage is misguided. To place a Christian in the story of modern academic life will not be sufficient to change the story. For example, I grew up imagining that the Christian story was heady. I lived in my brain. I could explain precise, doctrinal concepts to my peers. The evangelistic task was the apologetic task: defending the faith. I developed rational arguments for the existence of God. I could tell people how wrong they were and how right I was. But even if I knew all the right doctrinal beliefs, I had trouble living them out. Or more accurately, I did not really care to live them out, because I was right. And being right was enough. I had become a victim of the scientism of my day.

I think you can see this reality in the YouTube or TikTok world. He “owned” his “opponent.” She “destroyed” him with logic. Language matters. Such phrases designate people not as persons but as opponents. Arguments are not after truth; they are about embarrassing the other side. In an effort to be right, goodness and beauty fall by the wayside. Who cares if I’m kind as long as I’m right? Values flow from the story we tell.

Or if the story we narrate our lives by is one of career accomplishment, then achievement is what we are want. So we can live as Christians and make decent decisions and try to be kind, but getting ahead is what animates our life. The story we tell ourselves is that we are behind, and the reason we work hard is to fulfill our dreams—upward mobility with nice cars in nice neighborhoods with nice schools. Christians can live this story even as they profess a belief in a very different story. We must answer the question of what story we are a part of before we can answer the question of what we are to do.

Students come into the classroom carrying all different sorts of stories and many of them are not especially helpful. Our pilgrimage starts with the story we tell, which is one reason why the Christian story needs to be centered in a Christian education.

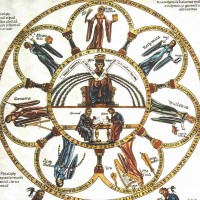

The pilgrim motif has long been a paradigm for the Christian life. The writer of Hebrews describes the faithful of the past as strangers and exiles on earth seeking a home which they never experienced in their earthly life (Heb 11:13). Even as Peter describes Christians as a holy priesthood and a chosen race, a few verses later he calls the church sojourners and exiles (1 Pet. 9, 11): travelers without a home. The fourth-century African St. Augustine picks up this theme as he describes our hearts as on a continual journey for rest or home. Dante, an Italian poet of the fourteenth century, penned a winding tale about the journey to God in his Divine Comedy. Within it, the soul is personified as it travels through different levels of the afterlife: through hell (Inferno), through purgatory (Purgatorio), and eventually to paradise (Paradiso). In paradise, the soul finally finds its ultimate rest as it rests in God. The hobbits in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings do not like adventure and would rather stay at home, but central to the story of The Lord of the Rings are hobbits who leave the Shire to accomplish a mission at the top of Mount Doom. Today, many religious traditions celebrate holy pilgrimages to certain cities or along certain paths seeking spiritual renewal and inspiration. Like Walker Percy mentions in the epigraph, there’s a homesickness that leads us on a pilgrimage.

In 1678, John Bunyan wrote a book called Pilgrim’s Progress. The book became a classic, and you may have read it growing up. Bunyan was a lowly tinker in England’s prestigious culture. He was not educated. He was not ordained. He fixed trinkets around the house and earned a meager income. He did not have status. But he was also a preacher, which made the powers that be angry. He was put in prison for holding a church service that was not approved by the official church. And in prison, this lowly, uneducated preacher writes a book that we still read nearly 400 years later.

The book is an allegory of the Christian life. He compares this life to a pilgrimage. A man named “Christian” is the main character. (Clever, huh?) He passes through different cities and different temptations. The Christian journey is not a one-size-fits-all trek. At different times–at different stages–we’re all exposed to diverse realities. What someone struggles with when they’re young may be something someone else wrestles with later on in life. What’s hard as a young adult differs from the challenges you may face on your death bed. However, we all pass through certain hardships with certain vulnerabilities on the pilgrimage of life, and Bunyan illustrates these realities through his story.

In Learning to Love, I take this paradigm of pilgrimage and apply it to certain realities in college. Each stage of college life has enticements and attractions that may lure students off the path. We need to do some deconstruction before we set a proper foundation for the pilgrimage. My goal is to re-image what education is—from a dry, stuffy, and dull task to a joyful, life-giving, wonderful journey.

The pilgrimage we are on is not limited but expansive. In the Christian liberal arts, there are multiple pilgrimages students make. Students journey backward into history to read about formative people and places. They journey inward into their own soul when they study psychology, philosophy, and literature. They journey to the outside world as they study biology, chemistry, and natural science. They journey upward toward God in studying theology. And there’s overlapping journeys within them all.

The Christian liberal arts invite us on these ventures and explorations. If we listen, they’re calling out to come explore, to come take a journey, to find a pilgrimage worth taking toward an end worth reaching.