The cargo space of Ralph Vaughn’s 2000 GMC van is lined with art. Through the window is one of his vegetable patches prior to this year’s growing season. Images by author.

Rising Fawn, GA. I was driving with my wife last year when an odd sight broke the monotony of rural Ga. 157. Brightly colored folk art covered a house, spilling into the yard where large crosses lay coated with reflective materials.

I parked in the graveled driveway. Ralph Vaughn, wearing a tattered, stained pullover shirt, shaggy gray-brown hair showing from the sides of a wide-brimmed hat, invited us in. Artwork lined the walls and ceilings of his studio home. Just as abundant as his art was Vaughn’s commentary.

“There’s thousands of stories here,” he said.

We soon learned that might not be hyperbole.

Vaughn has seen lots of jobs, lots of ministry, long before art broke into his life. He’s quick to talk about salvation, fulfillment of his visions, his art’s symbolism, miraculous healings (including his own), growing vegetables to provide for his family and the needy, his long battle with a drug operation next door, his counseling and donations to aid addicts and others, and his visits to sing at churches, some of them serpent-handling. Laced with these topics are diatribes over meth and alcohol abuse, pharmaceutical companies, abortion, rampant laziness and obesity, and the failure of government, the church, and society to right these wrongs.

So yes, Vaughn can come across as a rural version of a street-corner Jeremiah. But there’s more: a generous artist and farmer with an off-the-chart work ethic. A good old boy that you wouldn’t mind sharing a beer with, were he a drinking man.

“Most people find him peculiar but, to me, he is fascinating!” wrote Jane Horton, responding to my query after she posted on Vaughn’s facebook page. She went to school with his children, moved away and returned seven years ago.

Like her, I sensed something of the real deal. Even if the recounting of his testimonies and visions bore an overzealous spin, the art, the ministry, the sacrifice of his spartan lifestyle, the tireless labor of a wiry 82-year-old with a big smile – it all merited a second visit from my Atlanta home.

Rising Fawn sits on Lookout Mountain, a long Appalachian formation running from northeast Alabama through Georgia and into Chattanooga, Tenn. Its population of 3,500 includes Vaughn and family members who live on their 12 acres, where they raise vegetables and chickens. The name “Rising Fawn” comes from a Cherokee Indian chieftain who, according to custom, named his child after the first thing seen following its birth. In his case, the beauty of a fawn rising from its bed at dawn and bounding off.

That image contrasts with an ugly reality about the area. Rising Fawn is in Dade County, Georgia’s northwestern-most corner. It’s among the state’s worst counties for opioid abuse and infections from drug injections. Drug traffic is so bad in the region that a Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit Drug Task Force was formed in 1990.

Vaughn and his family witnessed the drug culture firsthand for almost four decades. The property adjacent to his, part of the same family inheritance, was controlled by a nephew and owned by another relative. Relatives ran a meth lab, grew pot, and sold pills. In later years, “We were dealing with those that came here as small children, with bicycles and tricycles,” he said.

His family resorted to praying, counseling those willing to listen, and working with law enforcement. “We were dealing with helicopter raids,” Vaughn said. “Dealing with bloodhounds chasing these guys.” At times he felt like the criminal justice system was more interested in bail bond cash flow, often $1,500 or $2,000 a pop, than in permanently ending the criminal activity.

Teresa Vaughn, Ralph’s daughter, recalled an incident when her young daughter was helping Teresa’s husband with farm work. “I’m a farm girl,” the daughter said to a young boy from next door who was hanging out.

“The little boy said, ‘I’m a pill boy,’” and Teresa’s husband asked what he meant. The boy, whose role was shuttling money and drugs between the house and clients waiting outside, changed the subject “because he knew he wasn’t supposed to say anything,” she said.

Teresa relayed such reports to the Georgia Division of Family & Children Services, later learning the results of their visit. “There was no working bathroom in there. They had buckets,” Teresa said. The representatives “had to walk over dead dogs to get to the kids.”

Yet no substantive action was taken. “After that, you pray, because some things are bigger than what we can deal with in the flesh,” she said.

Only the nephew and another relative were ever tried in court. The nephew went to prison around 2005, but his adult children sustained the operation. Upon release, the nephew was banished from Dade and nearby counties. Around 2014, the property was sold and the house demolished.

“The big hand of God cleaned it up,” Vaughn said.

As much as that was a relief for his family, years of contact with desperate drug users, combined with their word-of-mouth about Vaughn’s kindness, expanded what he calls his “street ministry” of counseling, witnessing, and generosity.

“Somebody needs food. Somebody needs the lights paid. Somebody needs a water bill paid,” he said. “It just goes on and on.” Some recipients return the cash, but “a lot of times it don’t come back.” When it does, it often goes to someone else with a fresh need.

Bella Donna, who moved to Lookout Mountain in 2018, met Vaughn over their common interest in sustainable gardening. “I know he tries to help anyone who walks through his door,” she wrote me.

Horton, the long-time family friend, wrote, “He has such a peaceful demeanor and truly loves people and has dedicated his heart and his life to serving us in an effort to save us. He is well loved by this community.”

Vaughn dropped out of school when he was 14 or 15 years old. His parents had a “volatile relationship,” so he left home early, Teresa said.

“I went to the cotton fields,” Vaughn said. He picked cotton with about 10 black women, earning a dollar an hour.

At 17, while working in Atlanta, Vaughn met a homeless man who invited him to a revival meeting led by A.A. Allen, a Pentecostal with a healing and deliverance ministry. “There he received the baptism of the Holy Spirit and started working for the Lord immediately,” Teresa said.

Not only did Vaughn get the treat of seeing Little Richard and his choir at one of the revivals, but the performance opened his mind to a vision of racial reconciliation: “Blacks and whites were shouting and dancing together, and getting healed together, and getting saved. They had found a God that there wasn’t no difference between.”

Vaughn went on to work as a welder, became a foreman, then moved into construction and remodeling, running his own company. As a seasonal sideline, he and his family sold their vegetables at stands in Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama.

“Over the years, he started switching over and donating more of the produce,” said his son, Jamie Vaughn. Some is distributed one-on-one. The rest goes to churches with their own distribution networks. “We’ll try to get word out if dad’s got a bumper crop, let people know they can come over and get some.”

Home-based farming, including its physical demands, has also become a theme of Vaughn’s ministry. “I’m trying to teach young people and old people of the nation: Take up your hoes and your garden and start raising your own vegetables,” he said. “I’m wanting a large farm, get people back to farming. But it’s a battle to get them to even move. Move in God, it’s good health. Move in God, it’slonger life. Move in God, things work out. A nation that forgets their God will be doomed.”

He said it’s all part of his message to drug users, as well as non-users, who refuse to work: “I say, ‘God worked six days a week and rested one.’ They don’t want to hear it. They don’t hear the word ‘work.’”

Around 2005, Vaughn began leading his family in prayer and care for his wife, Annette, who was diagnosed with cancer. Her death in 2009 prompted two big changes for him. The first came from wanting to distance himself from memories of Annette in their house at the back of their property. So he moved to the roadside house, now also his studio.

“No computers,” Vaughn said. “No cell phone, no TV sets.”

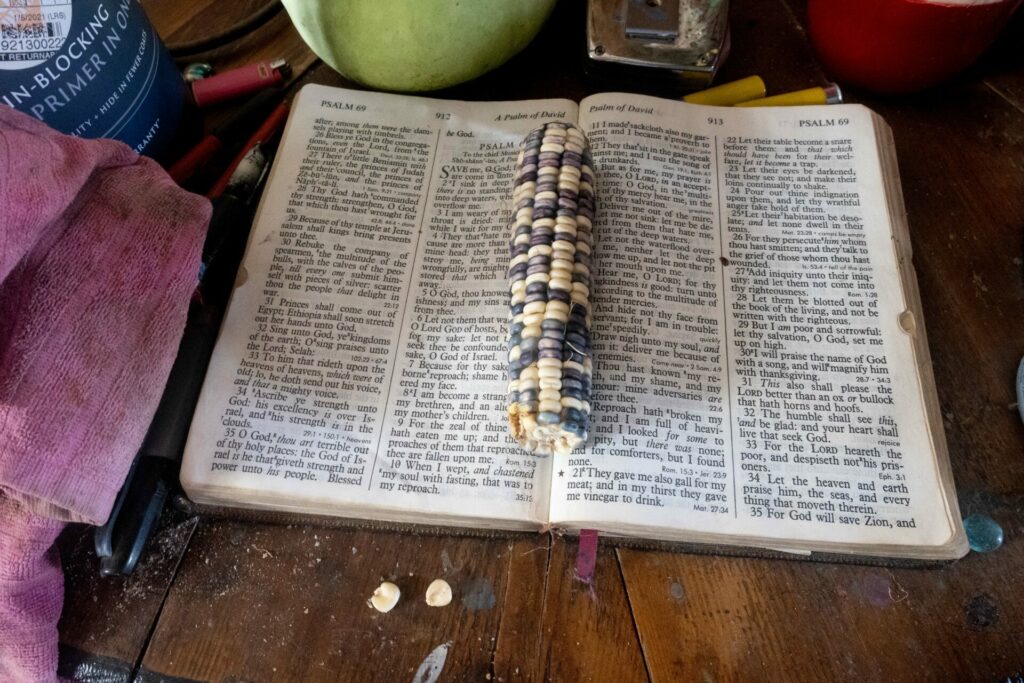

No problem. There’s also no air conditioning, so he has fans. No bedroom, so he sleeps on a couch. He cooks on one wood-burning stove and heats the home with another. Parked out front is his 23-year-old GMC Savana van, with his art painted on its interior walls.

For some meals, he eats prepared dishes or other food that friends deliver. “I am constantly buying him jars of peanut butter,” Teresa said. “He’s pretty much happy with whatever’s brought in.”

The bigger change for Vaughn after Annette’s death was sensing a divine call to art. Having no art training, he hardly knew where to start. For one early project, Teresa recalled, “He needed a horse, so he cut out the horse on a phone book at the time and used that as a stencil.”

Long before 2009, Vaughn experienced “visions” he believed were from God. Some come while asleep, others while awake. They can be specific for individuals or warnings for broader audiences, such as wildfires, drought, and tornados, all of which he and his family say were fulfilled. He’d always shared his visions with individuals, prayer groups, and churches, but with art he saw a new way to channel such promptings and reach a larger audience.

Vaughn’s typically letting paint dry on some pieces while continuing work on others. The creative pursuits don’t stop during the half of the year when he’s driving a tractor and doing the other tasks necessary to raise potatoes, green beans, sweet potatoes, kale, corn, tomatoes, cabbage, turnip greens, rutabagas, and peaches.

Supporters bring cans of paint and art supplies from yard sales and other sources. The ministry also benefits from financial donations, whether outright or in return for art or food. Otherwise, his income is limited to Social Security.

“I could already make all the money I wanted just by selling the pieces of art. I couldn’t draw it fast enough,” he said, but that’s not his goal. “As far as making any money, I may have $300 to $400 here. I got no banking account, no checking. It’s by faith.”

Vaughn’s creations make frequent use of broken mirrors, glass, rocks, beads, and other materials. Dozens are done on 12×18-inch heavy rubber shingles. Others are done on plywood, circular saw blades of varied sizes, and the occasional freestanding window, mirror, door, or whatever other cast-off object he’s found or been given. So many creations are done on 4×8 plywood sheets that some are stacked against walls for lack of display space. Quart and gallon buckets of ordinary household paint, with other art supplies and the miscellany of daily living, lie everywhere.

Sometimes days go by without any visitors, but other times Vaughn stays busy with friends or strangers who drop by.

“Some people say, ‘Ralph, you’ve got a gold mine sitting here,’” Jamie said. None of the artwork is priced, and most of Vaughn’s special works, such as those illustrating certain visions, are not for sale. He offers some pieces for free, and visitors who accept often will donate to the ministry. Holding on to most of his best work is one reason why there is no major collector of Vaughn’s art, which has received only scant public exposure.

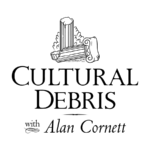

Many of the smaller pieces have no overt religious theme. His more elaborate work usually includes scripture or Christian phrases. Most also have graphics and labels that require Vaughn’s interpretations, which he’s happy to give.

It’s common for Southeastern folk artists, some of them preachers or ex-preachers, to focus on religious themes and quote the Bible. And it’s not unusual, as in Vaughn’s case, “to make statements about their belief systems,” sometimes “actually writing out messages,” said Katherine Jentleson, the folk art curator at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art.

The museum hosts a permanent exhibit of work by the late Howard Finster, Georgia’s best-known folk artist. His former home and grounds, Paradise Garden, is just 40 minutes south of Vaughn. It’s been preserved by a foundation as an art installation that’s also a tourist attraction, including overnight lodging.

Vaughn’s way of using certain artworks to portray the visions he believes God has imparted, including a predictive element, Jentleson said, is also characteristic of the genre.

“A lot of artists don’t go so far as to actually call themselves prophets, but they still have these kind of future-casting visions,” Jentleson said. “There’re so many artists throughout the history of art that identify in that way, not just self-taught artists. Having a sensitivity and an access to things that normal people can’t see or conceive of.”

Talk with Vaughn, Teresa, or Jamie and you’ll hear many future-casting anecdotes based on Vaughn’s visions. As with the earlier mentioned acts-of-God type disasters, family members say many others have come to pass.

Among the warnings they recount: more than a year before 9/11, visions “about big airplanes coming to tear your buildings down”; a week after Vaughn’s warning a woman of a serious health problem, she suffered a colon blockage, passed out in her yard, but had a “miraculous recovery”; an eagle, representing America, that was reduced to a drumstick, representing the nation’s bleak future if the drug culture continues.

It’s easy to be skeptical about the precision of prediction in such claims without clear documentation. However, on one major topic – COVID – posts by Teresa on her dad’s Facebook page, which she has administered since 2014, arguably tie his warnings to the pandemic.

At least a year before covid lockdowns gripped the nation in March 2020, Vaughn began receiving premonitions. “He said a lot of people are going to die. He saw a lot of crosses on graves,” she said.

In a Feb. 17, 2020, post, a few weeks before the first lockdown began, she wrote: “Dad had a vision about this creature in April of last year, he said it could be some kind of virus.” The post includes photos of Vaughn’s “killer bug” artwork, including one piece inscribed with April 2019. “It could be that coronavirus,” she wrote on Feb. 17. “He’s been praying against it all this time.”

Sure enough, a post from April 17, 2019, with a picture of the bug, referred to a vision of a “monster bug that hatched from the earth.” Vaughn’s bug renderings, unlike the spherical, spiky coronavirus images, look more like a scorpion. One of the most detailed versions of the bug is a furry, 5-foot-long, catfish-shaped sculpture, a work Teresa says her dad began prior to the pandemic.

In a Jan. 18, 2019 post – a year before America’s first confirmed coronavirus sample – Teresa passed along her dad’s warning of “a major disaster or attack!” and suggestions of massive financial aid and related fraud.

“He said he had a vision of Trump with money handing it out like federal aid,” she wrote. “He also said he’s gotten visions about mishandling of tax payer dollars as well. He wants to warn all he can.”

As 2020 progressed, widespread problems of fraud emerged with the federal Paycheck Protection Program for businesses. Other problems were tied to the billions of dollars hastily doled out in COVID unemployment relief.

While Vaughn interacts with churches through his food ministry, he doesn’t regularly attend a particular church, largely because he feels called to home-based ministry. Also, he’s hesitant to commit to church engagements. “If I leave here at 7 o’clock, a lot of times I got cars in the yard. Maybe somebody wants to commit suicide,” and they’re looking for counsel.

Further, Vaughn feels too many churches have “lukewarm” leadership, referring to the Rev. 3:16 rebuke of the church at Laodicea. “God showed me all the preachers of the earth,” he said. “Many of them’s got big arms full of fishing rods, but at the end of the fishing rod, look – no string, no hook and no bait.”

Still, he accepts some invitations to sing and preach at churches in his three-state region.

“Our ancestors actually come out of Harlan County, Kentucky,” he said. “A lot of them was serpent handlers.” One of the strongholds of that practice has been Alabama’s Sand Mountain. It’s just west of Lookout Mountain, across a valley. (Sand Mountain’s serpent-handling churches were documented in Dennis Covington’s fascinating 1996 book, Salvation on Sand Mountain.)

Vaughn and Teresa rattled off the names of serpent-handling churches he’s visited. One, Rock House Holiness Church in Section, Ala., on Sand Mountain, has photos of serpent-handling on its Facebook page. The number of such churches has dwindled, they said, due to state laws about protecting the snakes or requiring permits.

Vaughn said he hasn’t taken the faith step of picking up a poisonous snake during his visits. But if a pastor “got bit and couldn’t stay on their feet, I’d usually pray for them. Maybe two of us would keep them on their feet. Within minutes, they’d recover and they’d go ahead and preach their sermon.”

Like the anecdotes of visions and their fulfillment, the family members cite many testimonies of healings after prayer by Ralph and sometimes others: a 2-year-old grandchild suddenly stricken, apparently fatally, at a family gathering was revived; a woman who’d tried for seven years to get pregnant finally did, with twins; a man with two aneurysms in his head was retested at Vanderbilt and given a clean bill of health; a man, told he had two weeks to live, came to say goodbye to Vaughn and received prayer, but returned a week later, healed; a man who’d lost some mental faculty after a stroke received prayer, returned later, saying, “I sat on my couch and all the lights come on in my brain,” Vaughn said.

But the healing closest to Vaughn was his own. In his late 50s he’d developed pneumonia, followed by what his doctor suspected was mesothelioma. Vaughn attributes it to earlier jobs: handling too much asbestos and inhaling second-hand cigarette smoke and paint fumes. It had reduced his voice to a whisper. Imaging showed a huge growth in his chest.

“We really thought he was a goner,” said Jamie. He wanted to make as many memories with his dad as he could, so one evening he invited him to play some songs with him in a barn on the homestead where Jamie was living. “He couldn’t hardly walk up the stairs to the hayloft.”

After they’d played a while, “I noticed his voice changed. I didn’t think nothing of it at the time.”

Jamie’s mother told him the next day, “You know Daddy got healed up there at that barn.” A trip to the doctor confirmed it. Now, Jamie said, “He’s got a voice like a young man.”

Whether Vaugh’s visions, conveyed in words and art, precisely foresaw the pandemic or other events, or whether any of the testimonies of healings were as straightforward as recalled – in a sense it doesn’t matter. Vaughn’s not aspiring to be a Nostradamus or fund-raising televangelist.

“He’s not trying to make a name for himself,” said Jamie. “He’s trying to get himself to heaven. He’s trying to get as many as he can. A lot of people can’t believe that he cares about people so much.” Vaughn meets equal shares of belief and unbelief from those familiar with his visions, Jamie said. The doubters consider him just “a worn-out old man who lost his wife.”

Vaughn had already witnessed his own dramatic healing by the time Annette died. An adult daughter died a few years later from blood complications. So even after the family’s years of prayer for those two, he admits that God doesn’t always answer prayers to our liking.

“We couldn’t get a move of God,” he said, matter-of-factly, when asked about the deaths. “It’s like Job. His wife said, ‘Why don’t you curse God and die?’”

His art might never grace the walls of collectors or galleries or museums in his lifetime, but he and Teresa envision taking some of it on the road. The large crosses with reflective glass could be mounted on a flatbed trailer, other art displayed under large tents. He’d park anywhere he can draw bystanders – parks, tourist attractions, or truck stops.

Vaughn knows from experience art’s potential to draw crowds that can encounter the gospel. One instance was when he set up his work by Finster’s Paradise Garden for 30 weeks and lived out of his van. He’s staged similar displays during the annual event billed as the world’s longest yard sale, which runs from Lookout Mountain to Michigan.

“Anywhere you go,” he said, “art will touch lives.”

–

Ralph Vaughn has been known to pull out his guitar for visitors and sing. This video includes excerpts from three songs and views of his art-lined walls and ceiling.

5 comments

Jamie vaughn

My dad is truly an amazing person, I hope to become 1/3 of the man he is

Marissa

This is my grandpa. He is a Christian monk.

John Baxter

Wonderful article and story. I’ve noticed since moving to Mississippi that the Southern states have an entirely different spiritual perspective, one that 20th and 21st century technology have managed to erase in the Northeast.

Rob G

Can’t speak for New England but there are still quite a few traces of this sort of thing in rural Pennsylvania and Ohio. It always cheers my heart when I encounter one, and it’s become a habit to send up a prayer for the originators whenever I do.

Jonathan

Since moving to the Chattanooga area last year I’ve driven past Ralph’s place several times, stopping at times to admire the artwork, though not encountering Ralph himself, and thus not knowing- until seeing this article- who was behind it or why, Google searches turning up nothing (no small wonder, that!). Really wonderful to learn about the man behind the art, and will have to stop by again soon and say hi.

Comments are closed.