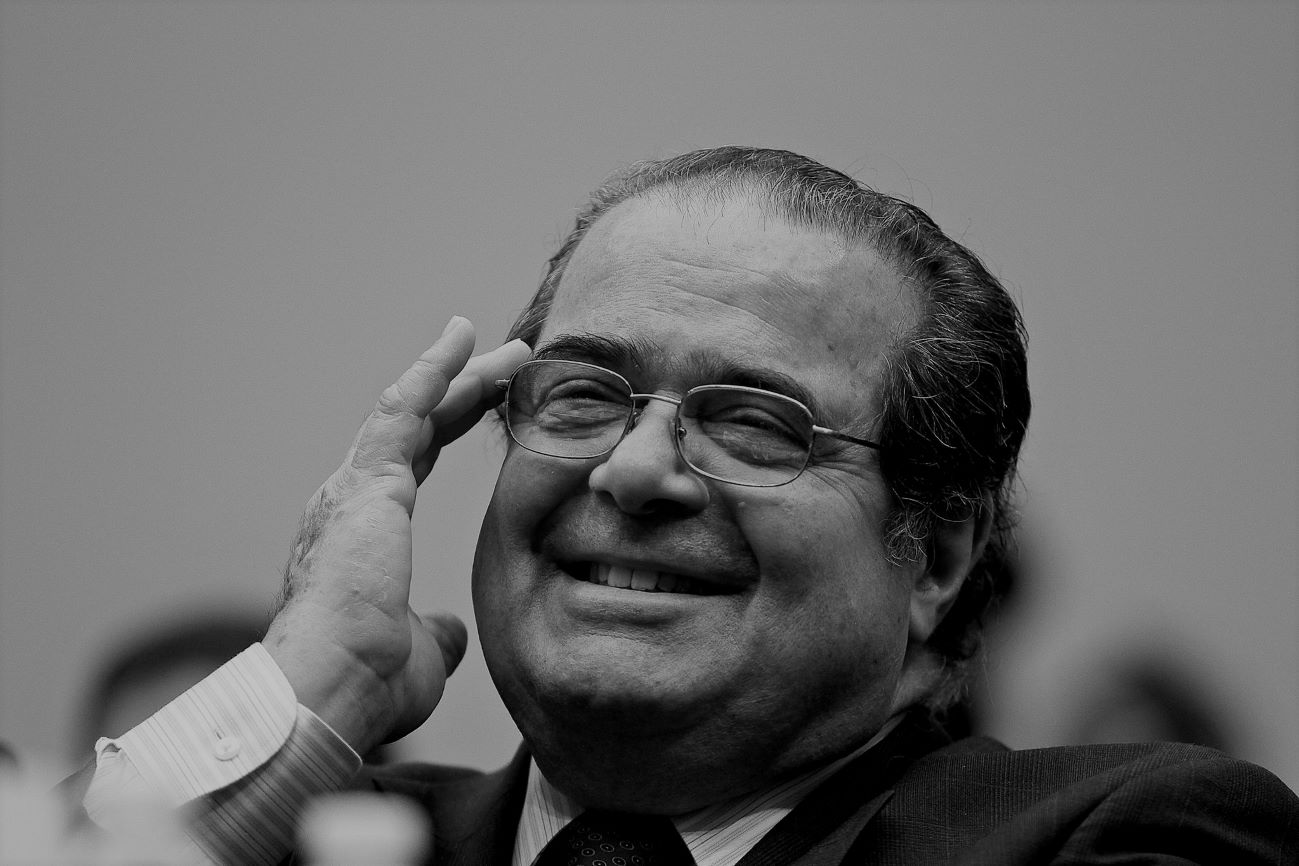

I’m going to the Supreme Court . . . I will rise.

– Antonin Scalia

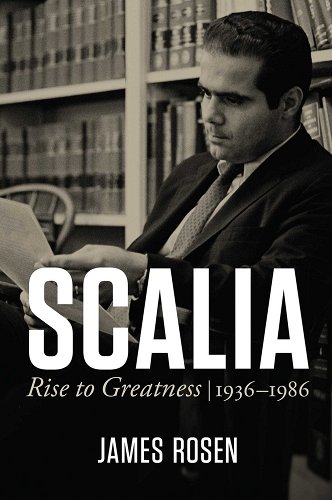

Livingston, MT. Antonin Scalia was among the most revered, respected, and hated figures in twentieth and twenty-first century American law. Along with Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas and to a lesser extent Justice Rehnquist and Burger, Scalia had a canny knack for drawing the ire of the New Left due to his embrace of social and religious conservativism as well as what has been called Constitutional originalism. Many of the biographies written about Scalia have been biased by this left-wing prejudice, depicting Scalia as a reactionary, authoritarian careerist. In his recent work, Scalia: Rise to Greatness, 1936-1986, journalist James Rosen, however, presents a more nuanced portrait of Scalia as an industrious and fair-minded Italian Catholic father and husband who worked his way from the streets of Queens to the “ivory temple” of the United States Supreme Court.

Although hailing from Queens, Antonin “Nino” Scalia was, in fact, born in Trenton, New Jersey to Italian Americans Salvatore Eugene Scalia and Catherine Panaro Scalia. Ironically, as revealed by Eugene Scalia (one of Justice Scalia’s sons), Salvatore or “Sam” Scalia had fled Italy due to his socialist agitating. The liberal father of the future Supreme Court Justice was noted for his singing and instilled in Nino a love of music as well as the ability to play the piano—a gift with which Nino entertained his friends throughout his life. Nino’s father Sam further went on to become a college professor of Romance languages, earning his Ph.D. from Columbia. Sam was very strict with Nino, pushing him to excel at academics and being (perhaps overly) critical when his son did not reach his high standards.

Like many children with strict parents, however, Nino was instilled with a lifelong industriousness and desire for excellence. Nino’s mother Catherine was, in Scalia’s own words, a “prototypical Italian mother,” who nurtured her son and raised him as a devout Catholic. As James Rosen notes, the hard work and desire to assimilate helped influence Nino’s later views on controversial issues such as affirmative action. Like many in the white working class—especially ethnic Catholic northerners—Scalia bristled at the idea that his Italian ancestors were responsible for slavery and/or beneficiaries of what in the twenty-first century would be called “white privilege.”

As James Rosen illustrates, Antonin Scalia lived a life in full—both as man and as a lawyer turned judge. Nino attended the Jesuit St. Francis Xavier high school in Manhattan where he was drilled in Latin, competed in debate, acted in plays such as Macbeth, and participated in the junior ROTC program. As Rosen notes, he would carry his drill rifle with him on the subway on the way to school. Nino attempted to get into Princeton after high school but was rebuffed (possibly due to anti-Italian prejudice). Undeterred, Nino applied to and was accepted into Georgetown, one of the “Catholic Ivies.” He then attended Harvard Law school, eventually breaking into the Ivies.

While at Harvard, he met and then later married the Irish-Catholic Maureen Malarky on September 10, 1960, in South Yarmouth, Massachusetts. Maureen and Nino shared a strong and vibrant intelligence as well as a deep Catholic piety in addition to a shared conservative worldview. Maureen and Nino would eventually have nine children, who themselves would excel in the world of “DC Catholics.”

As his career progressed, Scalia worked private practices interspersed with teaching at elite universities such as Stanford, The University of Chicago, and the University of Virginia. Scalia developed the reputation of a strict but kindly (and occasionally absent minded) professor of law. Known for his good humor, intelligence, and scholarly output, Scalia eventually worked as Assistant Attorney General in the Ford Administration and then as a judge in the DC Court of Appeals.

As he grew in prestige and prominence, like his colleague and friend Clarence Thomas, Nino began to draw the ire of the liberal press. The first major attack was an article titled, “Free Speech v. Scalia,” which ran in the New York Times on December 31, 1984. It attacked Scalia as being “the worst enemy of free speech in America today.” The Reagan Era also saw the death of Nino’s father Sam on January 6, 1986. True to his calling as a literature professor, Sam Scalia recited Thomas Gray’s somber, proto-Romantic 1750 “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” before his death.

That same year the door was opened for Nino Scalia to enter the Supreme Court. On May 27, 1986, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, a Nixon appointee tasked with rolling back the Frankfurter-Warren liberalization of the Court, set up a meeting with President Reagan. Burger, native of Minnesota, had decided to retire and an opening was available for a new conservative Supreme Court Justice. Both Scalia and Robert Bork were among the top choices. However, there was some concern about Robert Bork’s health as well as an alleged liberal or at least revisionist approach to originalism in some of Bork’s recent writings. The Reagan White House (rightly or wrongly) allegedly viewed Scalia as more reliably conservative. Moreover, they noted Scalia’s intelligence (a quality shared by Bork) as well his hard work. Finally, as Democrats and Republicans continued to fight for the Catholic vote, Scalia’s Italian-Catholic heritage was an added bonus.

Antonin Scalia was confirmed as Supreme Court Justice on September 17, 1986, after running the confirmation gauntlet that summer. During the Senate confirmation hearings, Nino was grilled by Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts as well as future president but then Delaware Senator Joseph Biden. Both Kennedy and Biden grilled Scalia on Roe v. Wade, but the Supreme Court Justice nominee deftly parried their thrusts. Scalia was likewise bombarded by six hostile expert witnesses (he had eleven in support of him), which included Eleanor Smeal, the president of the National Organization for Women, as well as a representative of The Nation Institute. Like Scalia’s Democratic critics, these expert witnesses focused on Roe v. Wade as well as Scalia’s alleged lack of sympathy for affirmative action programs.

Interestingly, as is oft forgotten, the concurrent confirmation of William Rehnquist as Chief Justice was much more contentious as Democrats brought out old and, according to Rosen, dubious accusations that Rehnquist had intimidated voters in Arizona. Scalia, however, was defended by a host of Democrats and Republicans, including the then freshman Senator from Kentucky, Mitch McConnell, who praised Scalia’s “independence.”

In his final chapter, Rosen also notes Scalia’s friendship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of the most prominent liberal judges on the Supreme Court during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Rosen’s key point in this episode seems to be that the charm that enabled Antonin “Nino” Scalia to excel and rise to one of the most important positions in American politics further also allowed him to reach across party lines when such collaboration did not conflict with the moral and judicial principles that guided him throughout his long and interesting life.

Antonin Scalia’s judicial legacy was ratified on June 24, 2022 as the Supreme Court effectively overturned Roe v. Wade with the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision. The majority opinion consisted of Scalia’s conservative colleagues Justices Thomas and Alito, as well as newcomers Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. Dobbs was not only a ratification of the post-Warren-Frankfurter conservative judicial movement that Antonin Scalia helped to energize, but it was a tremendous victory for social conservatives who had labored to overturn Roe for decades. The presence of younger conservative justices and the continued strength of conservative legal movements such as the Federalist Society give hope that the efforts of Scalia will continue to blossom in the third decade of the twenty-first century.

2 comments

John E. de Graaf

I’m sorry…senior moment. I meant Scalia, not Alito.

John E. de Graaf

While I generally love FPR for its localism, and very thoughtful conservatism (and especially the ideas of Russell Arben Fox), articles like this one just seem designed to further the polarization between localist conservatives and degrowth liberals like me. I don’t write pieces for this publication celebrating choice and don’t see the need to fight the abortion battle, which is so divisive, in a publication like this one, which can help bring us together. Can’t we find issues where we have common ground–sustainable agriculture, local control, environmental stewardship, skepticism of technology and certainly the targeting of children, rapacious capitalism–and avoid those (abortion, transgender issues) that simple drive us apart and make common ground nearly impossible. We both celebrate the grace and wisdom of Wendell Berry, Christopher Lasch etc. But Alito–one of the most divisive member of the Court? Please.

Comments are closed.