I can still recall the first time I billed more than three hundred hours in a single month as a young associate at a corporate law firm in the late 2000s. Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December, and our client, a successful software startup, absolutely, positively had to be sold by the end of the year. Or so the investment bankers kept loudly telling everyone. We worked sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, with Christmas off and an admonition to be back all the earlier next morning à la Bob Cratchit. After the deal finally closed on Saint Sylvester’s Day, with mere hours to spare before the ball dropped, I traveled home to Florida to see my parents and in so doing conquered an adult-onset aversion to flying. It turns out that it’s possible to be too exhausted to fear death.

As taxing as experiences like these were, they were not what ultimately drove me from the legal profession a mere three-and-a-half years after I had entered it (a career span which meant that I spent almost as much time studying to be a lawyer as I did actually being one). Three-hundred-hour months were not unheard of, but neither were they typical. And at least in their early stages, undertakings of that level of intensity can engender a certain amount of excitement and esprit de corps.

What I found harder to acclimate to than the occasional bouts of nonstop toil were the “normal” months—periods during which we worked hard, but not so hard that we had to spend every waking moment in the office. Or at least not physically in the office. Mentally, it felt as if there was no escape. You might not have any specific tasks or meetings scheduled for a given Saturday, but unanticipated requests from partners or clients could, and many times did, come in at all hours. And when they came in, it was with the expectation that they be responded to promptly. I rarely went more than an hour or two without checking my work email on weekends. Even when I wasn’t technically working, I never felt fully off the clock.

It was of this period in my life that I was thinking while reading Will Blythe’s thought-provoking Esquire essay “The Life, Death—And Afterlife—of Literary Fiction” (a title made all the more vivid courtesy of a header image of a tombstone emblazoned “Here Lies Literary Fiction”). Blythe, who cut his teeth under Esquire’s Rust Hills in the late 1980s, has written an elegy for an era when “magazines . . . stood rather jauntily in the center of American culture.” Back then, it seemed “that fiction in magazines would last, well, forever. As would magazines themselves. As would literary fiction, period, anywhere and everywhere.” Alas, the last twenty-five years have witnessed the decline of magazines generally and of their commitment to literary fiction in particular. Blythe quotes The Atlantic’s Executive Editor Adrienne LaFrance as noting that “[t]he thinning of print magazines this century meant a culling of fiction.”

Who or what is to blame for this fall from grace? For Blythe (and apparently LaFrance as well), the culprit is clear—the internet. Blythe imagines his own readers struggling to get through his piece on their devices, being bombarded all the while by “notifications, texts and emails, along with promotions, advertisements and daily venues of news, opinions and games such as Wordle and Spelling Bee.” This electronic onslaught constitutes a “digital switchblade” capable of slicing minds apart and preventing any reader from completing so much as a short story or essay. Where once Columbia English professors read five novels a month, they can now barely manage one. Too many web sites to check out.

The vision of the internet that Blythe summons up—as purveyor of “distraction as a form of entertainment, or entertainment as a form of distraction”—is one that no doubt rings true for many. I myself had been known to take an aimless spin through Twitter before Elon Musk turned it into even more of a hellscape than it already was. Yet in terms of impinging on my engagement with literary fiction, the real threat posed by the internet has been its role in eroding the boundaries between work and leisure. And it is not solely (or perhaps even primarily) about there being more hours of work and therefore less time for reading. It is about the possibility of work hovering over every moment of supposed leisure. For me, that is the fundamental distraction, not TikTok. So yes, smartphones are the problem. But they didn’t need to put all the wonders of the online world at my fingertips to become the problem. All they had to do was send and receive email like the original BlackBerry, and thereby create the expectation that one could respond to messages anytime, anywhere. (Relatedly, I derived immense satisfaction from watching the recent film depicting the collapse of Research In Motion, BlackBerry’s creator).

One of the details in Blythe’s description of his halcyon days at Esquire that struck me most were the three-Negroni lunches that he and Hills would sometimes enjoy. It’s not that I especially long for the return of booze-soaked workdays. I am a recent convert to teetotalism, my particular midlife crisis having manifested as a health and fitness kick that can accommodate either drink or dessert, but not both. (Let me eat cake.) Still, that such lunches once existed appears to confirm that more generally, the nature of work today is very different than I remember it seeming growing up.

Like Blythe, my father was in the magazine business. Someone at Time cut him a break and gave him a job answering phones after he left the Catholic religious order he had joined out of high school, a suddenly vocation-less middle-aged man with an advanced degree but a decidedly nontraditional resume. He ultimately worked his way up to become a senior executive in their customer service department. The odd three-hundred-hour month aside, my dad certainly did not work any less hard than I did as an attorney. He was often in the office before my brother and I woke up in the morning. But when he came home, he came home. With effectively no possibility of work intruding on his evenings, he spent them in the den, devouring books. One of the many small memories of my father that I will always cherish is the fact that his doctor used to schedule his appointments for longer than necessary just so he could use the extra time to ask my dad about what he was reading. (Apologies to anyone left languishing in the waiting room.)

It was not until I transitioned to a career whose lack of demands on my non-work life was more similar to what my father experienced that I rekindled my love for literary fiction. Blythe aptly describes the act of reading literature as a “slow drift into reverie, the immersion into the charismatic black-and-white grids of the page.” Such immersion is not really possible when you may be ripped from it at any moment by the angry red blinking of your BlackBerry’s email notification light (or its less outdated equivalent). It could be that some people are scrolling Instagram not so much because they prefer it to reading short stories, but because it is all their brains can handle when the prospect of work always looms.

Has literary fiction died? I don’t know. Like Blythe, I wince every time I take public transportation and find nary a book or magazine in sight save for the one in my own hand. (Although who’s to say that at least some of the people buried in their phones aren’t doing something worthwhile, like reading his fine essay?) Also like Blythe, I think fiction remains as exhilarating as ever. If more of us are to be able to seriously engage with it, we may need to channel our inner Bartleby (albeit hopefully with a cheerier ending): when our careers ask of us that we erase the boundaries between our work and leisure lives, we might consider responding “I would prefer not to.”

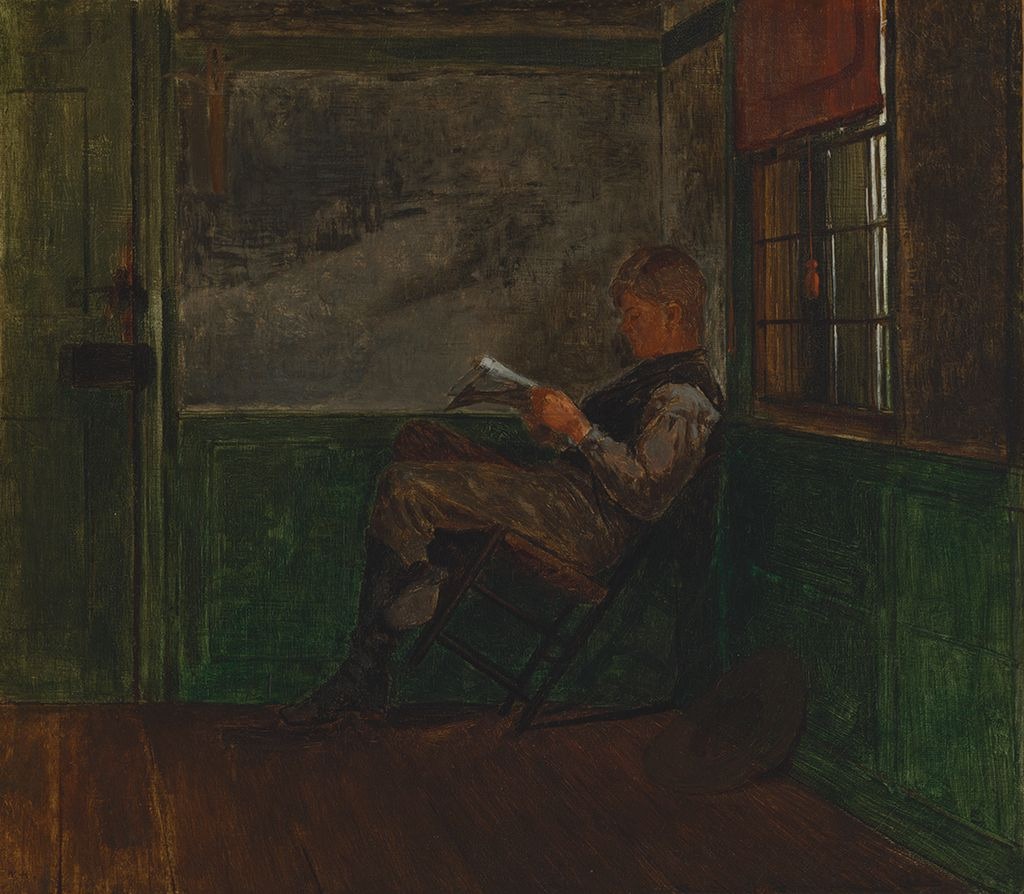

Image credit: “Young Man Reading” by Winslow Homer via Wikimedia Commons

4 comments

Martin

I agree with Brian, Zach, and Rob, but perhaps less with Rob because he seems to focus on non-fiction. As Christian notes, literature exercises the imagination without being tethered so tightly to knowledge of reality — thus the mental conflict with work or even more mundane tasks.

It’s tempting to consider McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” literally here: the nature of turning pages is not only part of the experience of reading, but perhaps also part of the actual message.

However, I still don’t understand the title of Christian’s piece. And I’m a little surprised to see him focus on a solitary author who wrote a (long) essay rather than a book. I would have enjoyed reading more of his personal experiences relevant to the topic, such as details along these lines:

“It was not until I transitioned to a career whose lack of demands on my non-work life was more similar to what my father experienced that I rekindled my love for literary fiction.”

Rob G

Actually, I think that the internet is to blame for the decline of reading in general. A friend who is a seminary professor constantly complains that the majority of his students have completely lost the idea that “knowledge takes work.” And one of the ways this manifests itself is in their inability to read and really wrestle with extended and/or complex texts. The ‘net has conditioned them to seek the quick and ready answer for everything. And of course by doing this it has simultaneously greatly reduced attention span.

I would add that it’s not just the technology of the ‘net that’s doing this, but the culture that necessarily comes with it. We are being formed by it, and both the self-centeredness and dumbing down are inherent in that formation.

Zach Boston

I think you hit on something very important. The expectations of total and constant availability that pervades our work culture is certainly a deeper reason for the decline of leisure reading than the technologies that enable the fulfillment of such expectations.

However, I still think the technologies in and of themselves, and not merely their role in blurring the boundaries between work and leisure, share some of the blame. Having had long periods of both work and unemployment in my life, I can definitively say that for myself, work interfered with my reading, but so did the constant allure of my smartphone, even when during periods of unemployment. It was only when I was both not working, and deleting all social media and deliberately leaving my phone out of reach that I was able to rebuild old habits of reading.

And, of course, I don’t think we can forget the effects of our values and what treasure as a broader culture, which both shape and are shaped by our expectations around work and our technologies. It is simply the case that we don’t really value reading or true leisure as is seen in Mark Bauerlein’s, “The Dumbest Generation” and Josef Pieper’s, “Leisure as the Basis of Culture.”

Brian

I guess it’s assumed we’ll all know and agree on a definition for “literary fiction” but it’d probably be a good idea to lay it out there so we all know what we’re talking about. To me it brings up visions of Jonathan Franzen, who I’ve never actually read because the reviews slobbering over him a decade ago made it seem so tiresome.

“The internet did it” is a convenient excuse for a magazine culture that has become radically disconnected from any audience except the tiny sliver of people who seem to spend all their energy talking about how white men are all bad and one orange man in particular is the worst of them all.

Comments are closed.