Arnold Lobel is justly famous, his legacy secured in the annals of children’s literature, for his Frog and Toad books, probably the most numinous celebration of same-sex friendship since Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. (Maybe amphibious protagonists lend themselves to explorations of friendship.) But I didn’t read those books as a child, and when I encountered them as an adult, they triggered a long-buried memory. When I was in first or second grade, I came into my room—this is the fragmented version of the story that presents itself to me three decades later—to find a picture book sitting there. Who knows where it came from? A child’s life is full of gifts from mysterious sources; for all I knew it had materialized out of the thin air. I read it again and again, and then more or less totally forgot about it until I stumbled across Frog and Toad all those years later.

The book was Lobel’s Owl at Home, published in 1975, a few years after the Frog and Toad series, and sharing a kind of spiritual universe with them. Like Frog and Toad, it is essentially a short-story cycle, or perhaps a very episodic novel, for young readers. (A badge on the cover says, “Grades 1-3.”) And like Frog and Toad, its simple text and slightly less simple artwork are by Lobel. Its content, however, is a kind of complement to the earlier series: whereas Frog and Toad are defined in relation to each other, Owl lives alone elsewhere in the forest and does not address another animal at any point in the book’s five chapters. It’s winter for much of the book, and presumably Frog and Toad are burrowed into the mud at the bottom of some pond, while Owl goes on with his life. Owl at Home is consequently an enormously lonely book—but it is a soft and shimmering loneliness, the sort of cozy loneliness that everyone with even a hint of introversion has felt at some point in their lives and enjoyed, on some level, at least.

The best children’s books understand that children are more in touch with the mysteries of the world than adults are, and they don’t explain too much. So there is usually a straightforwardness counterbalanced by uncanniness; the rules of the fictional universe are felt, not given, and reading such a book as an adult can crack the rational shell of the world open long enough for a little mystery to ooze out. This is especially true of children’s books that do not take children as their protagonists. Such books, written by adults and starring adults who are childlike in their most important features, have a disorienting and reorienting effect on their adult readers, especially adults who encountered them as children. They offer a kind of double or triple vision, wherein we see the world not as it is but as we’d imagined it would be. In other words, children’s fiction prepares the child for adulthood, though not in any straightforward or didactic way; it stores up the child’s natural reservoirs of imagination and mystery, which will be necessary to survive adulthood with one’s soul intact.

Owl at Home is thus what we might call a soulful book, and its adult readers (especially those who first encountered it in childhood) will recognize its idiosyncrasies, coded into their own psyches. It opens, appropriately enough, with Owl at home. Lobel does not bother introducing us to his protagonist, perhaps because, as with so many semi-archetypal characters, we somehow met him in the dark forest before our birth. It’s a winter night; Owl is beatifically eating his modest dinner of “buttered toast and hot pea soup” when a wild knocking comes from his front door. Here too there are shades of The Wind in the Willows, specifically the chapter in which we learn that grumpy old Badger opens his own cozy home to any animal lost in the snowy Wild Wood. Only Owl is not grumpy, and no one is lost in the woods. It is, Owl discovers, only the winter wind knocking at his door—at which point, as part of the book’s project of total anthropomorphism, he decides Winter must want to warm itself by his fire.

Owl’s thought process is fundamental to Lobel’s aesthetic and psychological project in Owl at Home. A different book—a lesser book, I think—would emphasize Owl’s isolation here, suggesting that his invitation to the Winter is an expression of his own desire for companionship. But that’s not what Lobel does. Owl invites Winter in out of an overabundance of happiness, or perhaps we should say contentment, a quieter and less negotiable term. He loves his strange little life so much that he wishes it for everyone else, even the seasons.

And why not? It is, after all, the Winter that makes Owl’s cozy evening possible; in the book’s dream logic, it’s only fair for it to take part in the pleasure. But even in Owl at Home, the Winter can’t enjoy such a life, which depends on it for contrast. The wind and snow rush in, slamming Owl against the wall, and despite his vocal protests, they blow out his fire and turn his soup to solid ice. Betrayed, Owl orders Winter to leave and relights the fire. Then he returns to his quiet evening, his soup, and his fire. He has scarcely been disturbed—certainly not permanently.

Owl seems to have learned his lesson by the time of the book’s final chapter, “Owl and the Moon.” Here he goes out to the seashore and watches the full moon rise with great interest. His reasoning, again, is subject to the dream-logic of children’s books: “If I am looking at you, moon, then you must be looking back at me. We must be very good friends.” But he knows better than to invite the moon home, since it wouldn’t fit through his front door. Instead, he instructs it to stay over the ocean, which he takes to be the moon’s home.

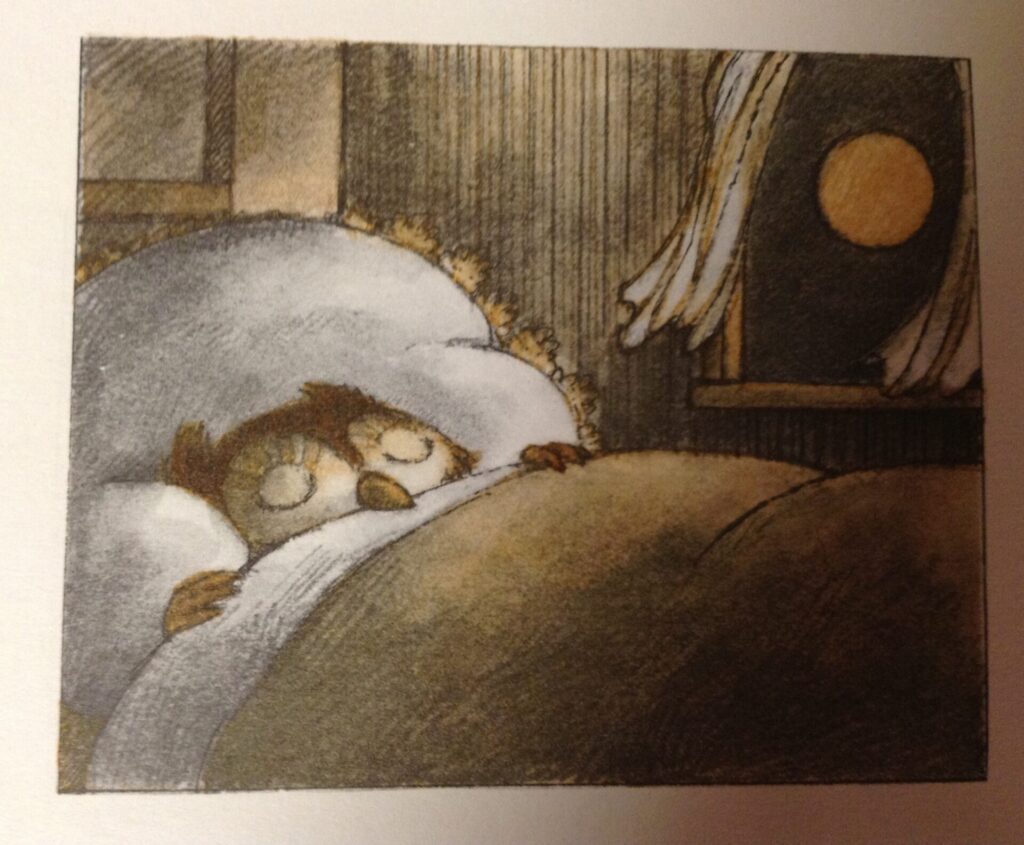

Of course, it follows him home anyway, causing Owl some amount of distress; no doubt he remembers the mess that Winter made of his quiet evening at home. Finally, as Owl arrives at home, the moon goes behind the clouds, and Owl falls into a deep melancholy, putting his pajamas on in the gloomy darkness. Just then, the clouds part, and Owl sees his friend shining in the night sky. The book ends with a benediction of sorts: “Owl did not feel sad at all.”

Both of these stories demonstrate the degree to which Owl is given to misunderstand the ways of the world. Such misunderstandings are a staple of children’s books: think of Peggy Parish’s Amelia Bedelia books, where the title character never meets an English idiom she doesn’t take literally. But Owl’s misunderstandings are played for more than comedy; his confusions get at some higher form of tragic wisdom.

Take the fourth chapter, “Upstairs and Downstairs,” in which Owl realizes to his sorrow that when he is upstairs, he cannot be downstairs, and vice versa. Thinking he can outwit reality, he decides that he can bilocate if only he moves faster, and Lobel’s drawings transform him into a blur of brown feathers and his striped bathrobe. But of course it doesn’t work, and Owl learns, as we all must, that his life has limits that he did not choose for himself. Tired and disappointed, he sits on the tenth stair, halfway between upstairs and downstairs, and the child-reader instinctively understands what Owl himself surely knows: now he’s neither upstairs nor downstairs. It’s a minor tragedy, not unmixed with comedy—but then most of our lives are low-level tragicomedies based on limitation.

Owl’s strange wisdom, his contented sadness, reaches its apex in the story “Tear-Water Tea,” which ushers children into the soul-level sorrow of the world. One evening, Owl decides to make tear-water tea, a concept Lobel brings up as if it were something we all did every few weeks. As we soon learn, one makes tear-water tea by forcing oneself to be sad and to weep so much as to fill a kettle with tears. (There’s that dream-logic again.) Owl’s melancholy—self-induced but probably not far from the surface to begin with—revolves around the sadness of loneliness. But he does not think of himself. He thinks of various forgotten objects in the built world of culture:

Songs that cannot be sung because the words have been forgotten. [ . . . ] Spoons that have fallen behind the stove and are never seen again. [ . . . ] Books that cannot be read because some of the pages have been torn out. [ . . . ] Clocks that have stopped, with no one near to wind them up. [ . . . ] Mornings nobody saw because everybody was sleeping. [ . . . ] Mashed potatoes left on a plate because no one wanted to eat them. And pencils that are too short to use.

Children are inchoately aware of the sadness of the world; it’s another of the human mysteries that they already have access to. Lobel’s genius is in choosing for his subject tragedies that are too small to really qualify as tragedies, and thus by the paradoxes of the spiritual world become the deepest and most incandescent tragedies of all. The tragedy of the used-up pencil is all the more powerful because the pencil cannot express it: if we don’t weep for it, Owl asks us, who will?

And yet even this sadness is part of the cozy loneliness of Owl’s life. After he fills the kettle with his tears—after he has made his connection with the quotidian despair of the world—he sets it to boil and then drinks it, reintegrating his own tears with the rest of his body. “Tear-water tea,” he remarks, “is always very good.”

Autobiographical readings of fiction—particularly children’s fiction—are usually a pretty sketchy enterprise, and yet Lobel’s oeuvre does seem to call out for it. Lobel’s daughter Adrianne, interviewed by the New Yorker a few years ago, says, convincingly, that the Frog and Toad books were at least somewhat connected to her father’s homosexuality. The two of them, she says, are “of the same sex, and they love each other [ . . . ] It was quite ahead of its time in that respect.”

This is not, let me be clear, a matter of reducing the rich relationship between Frog and Toad to a romantic, let alone a sexual, relationship; modern culture’s insistence that close friendships are always masking sexual desire is one of its most dysfunctional reductionisms. But it is quite reasonable to suggest that Lobel’s own feelings for men were part of the primordial soup of emotions, archetypes, and ideas out of which Frog and Toad evolved, no doubt only partially under their creator’s control.

Likewise, the timing of Owl at Home is surely relevant. The New Yorker article reveals that Lobel came out to his family in 1974, four years after the first Frog and Toad book was published and, more to the point for our purposes, one year before Owl at Home. I cannot imagine the anguish Lobel must have gone through as he prepared to tell his secret to his family; nor can I imagine the loneliness he must have felt afterwards. Or perhaps I can imagine it, because perhaps it is the warm and pleasant loneliness of Owl at Home, the book into which Lobel’s experience was transmuted and alchemized. Owl’s loneliness—and maybe Lobel’s, too—is the benevolent loneliness born of living the life given to you. Again, Owl at Home is in no sense an allegory for coming out or for anything else; had Lobel written that sort of book, it would lose its mythological power to its didactic purpose. But Lobel’s loneliness becomes universalized instead of narrowly autobiographical or (God help us) political, and so Owl at Home maintains its strange, subterranean pull that drew me so powerfully in the late 1980s and doubtless continues to draw children to it today.

Image credit: via Wikimedia Commons

6 comments

Derek

I recently remembered this book. I got it from the library, found the original Arnold Lobel audio online, and listened/read along with my three girls last night. It seemed to intrigue them in a unique way. The cozy melancholy of Owl’s life is suffused throughout the world of this little book. The world almost becomes a character in itself which is why Owl never feels lonely. And the way Owl relates to and thinks about the world is strange and mysterious. He sees clearly something about life that we feel intuitively but never quite grasp. The tear-water tea chapter is brilliant. Owl knows how to turn sadness into something pleasant and comforting. And I think that’s part of Lobel’s genius: he takes what an outsider might see as a sad and depressing life but shows us that life from the inside. A life that is content in being small and takes pleasure in being quaint and unobserved.

Frog and Toad were my favorite books for a period in my childhood and Owl At Home felt like part of that universe as you suggest. My girls asked if we can read it again tonight. I’ll have to break out the Frog and Toad books soon.

Reading last night made me look up other people’s thoughts on this and I stumbled on your blog. Great thoughts and insights. What you say resonated. I hope kids continue to discover this little book.

Pierre

This thoughtful reflection is much appreciated. I never read these books as a kid, but I do very much related to the sensation of “cozy loneliness”. It’s something I find myself frequently cultivating, intentionally or not, in my own home. I’m a gay man as well, and I really appreciate your observation that Lobel’s books would have lost their “mythological power” had they been a straightforward coming-out metaphor. It happens that a lot of my fellow gay people have an enthusiasm for the very “dysfunctional reductionism” you describe, reading same-sex attraction into any historical fiction/stories about two men, which absolutely blunts the universal power of the narrative (doing this to the story of Jonathan and David from the Bible is an instance that especially irritates me). There are many to whom it never occurs that insisting on one’s specific experience being reflected in art can foreclose more imaginative possibilities that open it up to others. As you say, though, certainly Lobel’s particular experience – primordial or otherwise – had to emerge in some sense in his work, if only through archetypes.

I do struggle with “the benevolent loneliness born of living the life given to you” (though it is a beautiful turn of phrase). I wouldn’t describe myself as particularly pleased or happy to be gay; it just is a fact about me. That it has led me to live on my own for many years, to the point now where most of my friends have gotten married and are starting to have kids, has led me to feel lost and left behind, even though I very much desire to find a spouse, as they all have. I can pray for contentment like Owl’s, but at the same time, I don’t wish to resign myself to this state of affairs. Perhaps there exists something in between, where we can reach for ‘benevolence’ of what is while working to discover what might not be yet. I don’t know.

Elizabeth

Thank you for this lovely meditation. As it happens I just read and thoroughly enjoyed Owl at Home with my young children (as we have all the Lobel books we have encountered thus far). You have articulated wonderfully some of what Lobel offers. He has certainly left a dusky, warm and ultimately loving atmosphere, full of humour but also of mystery, in my memory from my own reading of him as a child. Reading him as an adult, that dream-logic and touches truth. Deeply grateful for him and for your appreciative essay.

Art Kusserow

As a 71 year old I never remember reading many “children’s books” per se, unless you consider things like the “Tom Swift” series and “Dally, The Firehouse Dog” literature: hardly. It’s delightful to read a reflection on latter day children’s literature such as Lobel’s. Thank you for for this essay.

Scot Martin

Thanks for a wonderful meditation that brought me back to some good stories of my childhood in the 70s.

Dutch

What a lovely meditation on a great artist and a beautiful little book. We read the Frog and Toad books to our own children 30 years ago, and we’re reading them to our grandchildren now. I appreciate the reminder to explore the rest of Lobel’s books. And I’m off to explore more of your own work, Michial (I’m new to the Front Porch Republic readership.. just found the site). Thanks.

Comments are closed.