Over four days in July 1965, many of the era’s most influential songwriters and musicians gathered at Rhode Island’s Festival Field for the Newport Folk Festival. Acts such as Joan Baez, Mississippi John Hurt, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Bill Monroe, Gordon Lightfoot, Pete Seeger, and Johnny Cash all graced the stage. The final day of the fifth annual installment of the festival is perhaps most famously, or infamously, known as the day one prominent folk singer changed his style. Launching into an electrified version of his “Maggie’s Farm,” Bob Dylan was met with a chorus of boos and jeers. While historians often remember Dylan’s electric set, they generally fail to mention that a short time following his acoustic encore, another powerhouse took the stage. When she did so, though, Fannie Lou Hamer’s message and style remained the same, sounding once again the chimes of freedom.

This moment was not the first time these two major voices had shared a common ground, however. Two years earlier in July 1963, Dylan had joined Pete Seeger in Greenwood, Mississippi, to support the efforts of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). A month earlier, thirty miles away Fannie Lou Hamer and five other SNCC activists were brutally beaten at the direction of six white men: the sheriff, the jailer, and four police officers. The beating, which physically and emotionally haunted Hamer for the remainder of her life, kept the woman from being at the Greenwood office a month later to sing along with Dylan, Seeger, and the Freedom Singers.

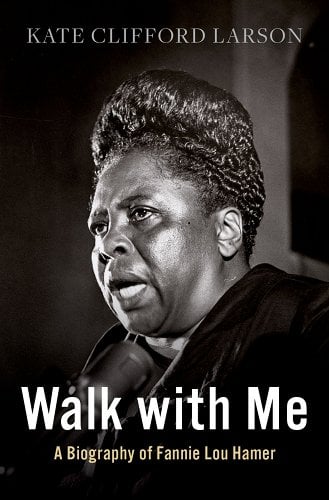

While the above two paragraphs illustrate only a few of the significant possibilities offered by a critical biography of Fannie Lou Hamer, they barely scratch the surface of this woman’s life, legacy, and influence on America’s civil rights movements. In Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer, Kate Clifford Larson moves deeper than surface-level observation, vividly using her sources to argue that Fannie Lou Hamer’s work demonstrates ways “ordinary people can organize and build coalitions that can create momentous, perhaps even lasting change.”[1] Situating Hamer’s activism within the larger context of the civil rights movements, her biography persuasively reveals how important one’s commitment to place can prove in the process of forging an activism that joins the local to the national and the international.

In many ways, Walk with Me is an ordinary biography, following its subject in a rather straightforward manner. Larson makes use of valuable primary sources—from newspapers to interviews to archival collections to recently declassified and unredacted files from the FBI and Department of Justice—to recount the narrative of Hamer’s life. Within a few pages, Hamer’s birth in Choctaw County, Mississippi, is mentioned.[2] On the final page of the final chapter, Larson writes of the activist’s death and funeral in Ruleville, Mississippi.[3] The life that fills the pages in between, however, is anything but ordinary. This female sharecropper from Mississippi left a legacy that reached far beyond her homes in the Magnolia State’s Choctaw and later Sunflower counties. But Mississippi always remained at the center of her concern and work. Unlike Bob Dylan, who famously visited the SNCC offices in Greenwood, Mississippi, in July 1963, Fannie Lou Hamer likely would have instead sung that the only one thing she did wrong was not stay in Mississippi long enough.[4] And I think that fact is one of the values of this study.

As Larson situates both Hamer’s labors in Mississippi and her commitment to her native state within the context of civil rights movements writ large, she demonstrates that Hamer was never only a pawn in the game, to use a phrase from Dylan’s song about the assassination of activist Medgar Evers.[5] On the local and the national levels, Hamer was her own person. She was dedicated to civil rights movements, especially the nonviolent versions of such campaigns, but on her own terms. As her focus on voting rights, segregation, sexual abuse, and poverty all illustrate, Hamer struggled for more than simply civil rights. She fought for human rights—in Mississippi, in the United States, and, after her visit to Africa in 1964, around the world.

As Larson illustrates so well, Hamer envisioned such an understanding of the universality of human rights, which went beyond simply encouraging African Americans to claim their constitutional right to vote, as common sense. Thus, she also argued against forced sterilizations and poor healthcare options, offered solutions to rural poverty, and decried American involvement in Viet Nam. On all such issues, Hamer spoke out forcefully and prophetically beginning as always with Mississippi as her backdrop. Without her consent or knowledge, Hamer received a complete hysterectomy in 1961.[6] These all-too-common “Mississippi appendectomies” played a role in Hamer’s push for quality health care and affordable clinics throughout the rural south. In the late 1960s, Hamer struggled for rural, poor Mississippians of all races as she labored for the implementation of Head Start programs in the state and founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative to aid fellow citizens of her state with basic needs of education and food resources.[7] She also rooted her critique of the ways that America’s masters of war participated in the war in Viet Nam in her concern for the local.[8] Hamer wondered how America could spend “so much money to fight a war to liberate people in Vietnam and not provide freedom for citizens in Mississippi.”[9] Driven by her commitment to place, Fannie Lou Hamer pursued human rights.

Like Bob Dylan, Hamer’s life was marked by protest and songs of protest. Her protests, however, grew from her personal experience on the ground in Mississippi. Kate Clifford Larson’s Walk With Me demonstrates this rootedness in the local and Hamer’s commitment to place in meaningful ways. Not only does she show how the civil rights movements were occurring outside of the Magnolia State, but her portrait of Fannie Lou Hamer documents the ways that Hamer worked to make her not-so-little light shine brightly first at home and then across the country and throughout the world.

Larson, Kate Clifford. Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: Oxford

University Press, 2021

-

Kate Clifford Larson, Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 234. ↑

-

Larson, 6. ↑

-

Larson, 231. ↑

-

Bob Dylan, “Mississippi,” Track 2 on Love & Theft. Columbia, 2017, compact disc. ↑

-

Bob Dylan, “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” Track 6 on The Times They Are A’Changin’. Columbia, 1963, vinyl LP. ↑

-

Larson, 48. ↑

-

Larson, 229. ↑

-

Bob Dylan, “Masters of War,” Track 3 on The Freewheeling’ Bob Dylan. Columbia, 1963, vinyl LP. ↑

-

Larson, 220. ↑

Image credit: “Fannie Lou Hamer” via Wikimedia Commons