It’s said that seeing is believing. And even sleight-of-hand may be caught in the act if you watch closely enough. But things began to change with the use of computers to produce photoshopped images, and now with Artificial Intelligence used to develop images and videos to purposely distort our understanding of reality, we’re into some deep trouble.

Sorting truth from falsehood has been a concern even from ancient times. Aristotle said, “To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true.”

If only things could be that simple now. Aristotle only needed to be concerned with what people said. And now we must discern the truth of what we see, also. AI may offer wonderful things to the world but will likely have its greatest impact in distorting the truth.

We’re about to be overwhelmed, and few are prepared to resist the onslaught of destructive misinformation folks all over the planet will be forced to endure. That leaves us with the question, “is there some way to prepare each of us to better discern fakery, find truth, and restore a common framework for understanding the truth and each other? Powerful fakery now lies in the hands of those who’s intention to inflame has the potential of setting our whole world in flame. People insufficiently connected to the fabric of community and culture are too often ready to light the match.

To better combat the destructive use of AI, citizens need to relearn the lost art of personal scientific inquiry, of learning from direct experience to build a structure for evaluation of belief. The point is not so much to combat individual bits of misinformation as it is to foster more discerning humans. And it can start with children, specifically with the proven strategy of introducing them to the manual arts at an early age, where they can learn about the real world, learn about each other and themselves, and learn more directly about cause and effect.

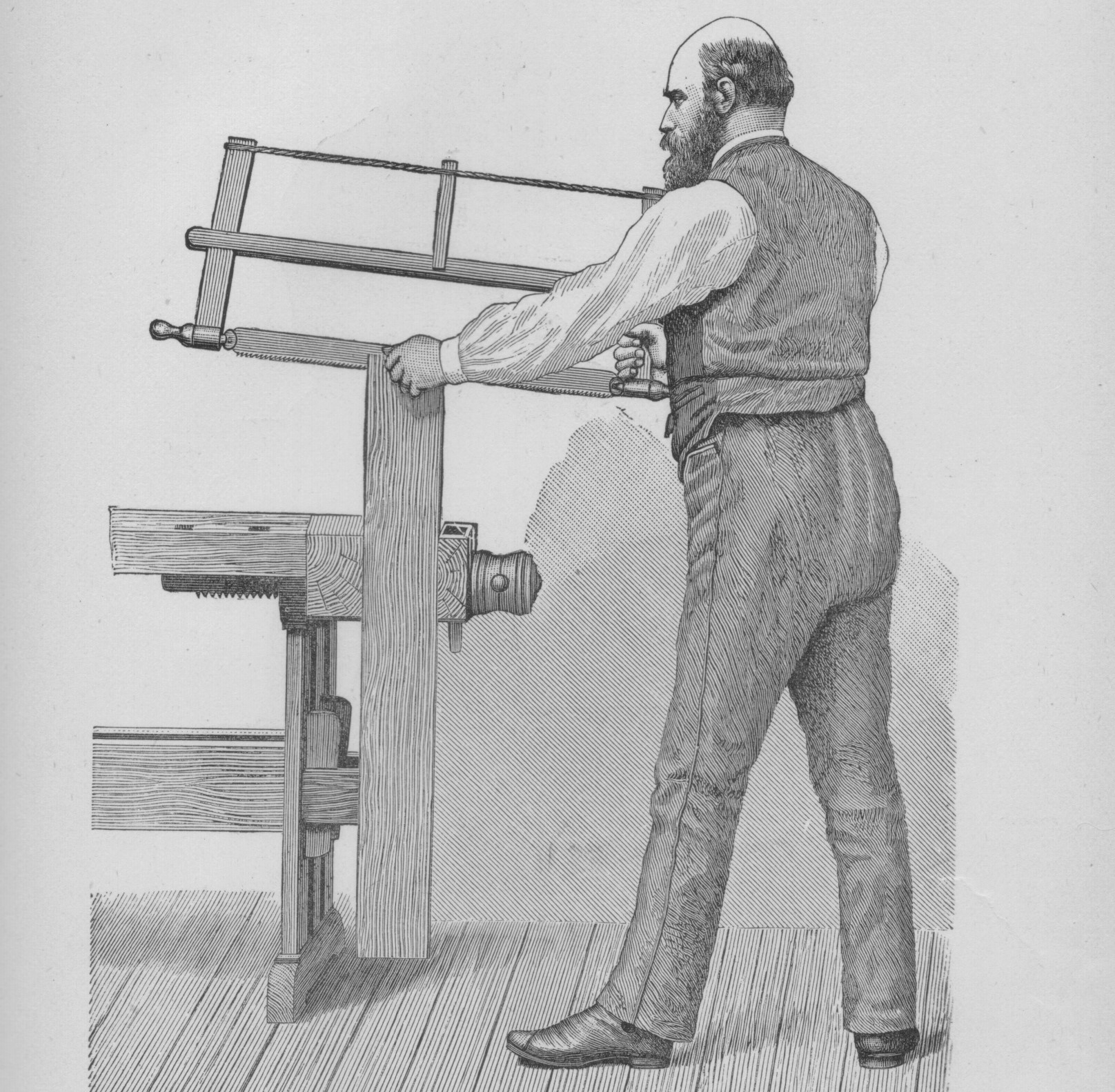

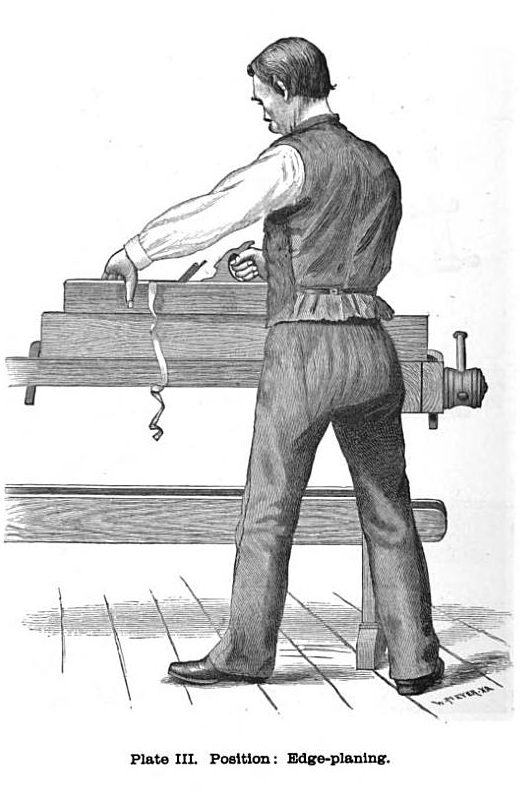

There are two very good reasons to study history. One is to avoid the mistakes of the past, and the other is to remember the great notions that were senselessly abandoned. In the early days of manual arts training in the U.S., there were two rival systems introduced. One was called the Russian system, it having been introduced from Russia. Its purpose, at the beginning of our industrial age, was to develop a skilled workforce capable of running the machines. The rival system was introduced from Sweden and Finland and was called Educational Sloyd, or the Swedish system. It had purposes beyond that of simply training folks for industrial employment. Inspired by Friedrich Froebel’s original Kindergarten, it aimed additionally at developing a citizenry in which all people felt respect for each other.

While Kindergarten has become for most “the new first grade” where reading is emphasized as a primary goal, Froebel’s original Kindergarten was intended to help children find their own interconnectedness with all life and with each other. That’s why they raised small animals, went on nature hikes, and played with a series of gifts Frobel invented that had the purpose of helping students understand the world. Through songs and music, they studied the contributions of others in their communities.

In a similar vein, Educational Sloyd was first developed by Uno Cygnaeus, a Lutheran priest chartered by the Russian Czar to develop a system of Folk Schools for all Finland. To do that, he traveled all over Europe to find a system worthy of emulation. He found it in Froebel’s Kindergarten. While Kindergarten focused on the youngest children, 3 to 8 years old, Cygnaeus offered craft education for the upper grades, extending the kindergarten methods of direct learning throughout the school years. Cygnaeus’s purpose in using manual arts was not purely economic as in the Russian system that aimed only at developing an industrial work force. Educational Sloyd aimed at developing a wholesome society in which students knew how to make a living, how to better understand themselves, and how to get along with each other.

To do that, Cygnaeus insisted that all children needed to be trained in the manual arts to understand and respect all labor—even those who might never pick up a tool must know the value of work done by others. Shared experience is a building block for a successful society.

Educational Sloyd was introduced in the U.S. at the same time and by the same enlightened folks who were introducing Froebel’s Kindergarten in the U.S. The Kaiser in Germany had shut down Froebel’s Kindergartens, as a threat to his autocratic state. Kindergarten with its sister, Educational Sloyd, offered a democratic ideal of a society in which we would each find greater community, commonality, and trust in each other.

Being raised by a Kindergarten teacher/mother, and a father deeply appreciative of the manual arts, I had an interesting experience in high school. My sophomore biology teacher, K. Fred Curtis, required us to take a standardized test to determine our comprehension of biology. He was impressed by my having scored in the 99th percentile, and as no other student in class came even close, he asked me to stand up and be recognized for my achievement. What I hadn’t the courage to tell him was that none of the questions on the test were related to anything I’d been taught in class. Nor were they related to anything I’d learned on my own. My achievement was simply that of sorting those things that were likely true from those things that were clearly not, an aptitude likely instilled in me by experiences my Kindergarten teacher mother had planned for my sisters and me. What happened was that my having some experience in the real world, I think, gave me a foundation for discernment in separating the truth from stuff made up to resemble the truth.

With the rise of Artificial Intelligence, it is more important than ever that we develop a common framework of understanding rooted in the senses—sight, sound, and touch—offline, in the real world. The hands have a particular role, as the eyes and ears are easily deceived. The hands measure the weight, size, density, and texture of objects, and thereby help us all to better build a shared framework for discernment of truth.

Work with the hands is an equalizer. It helps those who may not yet be academically inclined to demonstrate expertise. When schools took on the role of sorting kids, some for college and some for the trades, it was disastrous. Some students were targeted upward and some down based on standardized tests that we know to be faulty and biased. And separating hands from head proves detrimental to both.

Part of the problem is that children do not mature physically or mentally at exactly the same pace. Some children walk at 9 months and some much later, and yet that pace has nothing whatsoever to do with their ultimate development. Nevertheless we put children in classrooms expecting all to read at nearly the same time and have near conniption fits if our own child is not on the contrived track. The consequences are disastrous, in that putting children on divided tracks fails to recognize the full breadth of their potential.

The way the hands bridge between the arts, science, and religion is directly associated with the way we learn. This was described by Diesterweg (an associate of Friedrich Froebel) and was described by Otto Salomon in the Theory of Educational Sloyd:

We start with interest of the child. We build from the known to the unknown From the easy to the more difficult From the simple to the complex and from the concrete to the abstract.

Anyone who has sincerely bothered to review their own learning experiences will recognize the truth of Diesterweg’s theory.

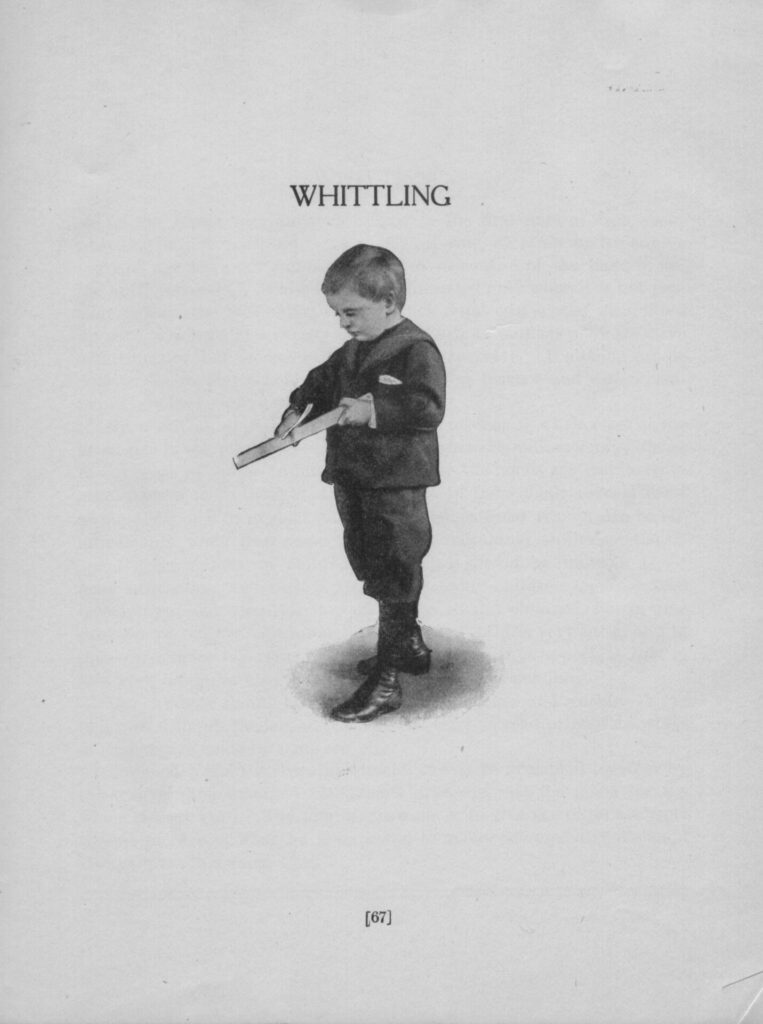

In Educational Sloyd the knife was the beginning tool in a series of exercises to build skill and understanding. The knife was the first tool introduced because in that era, all children in Sweden and Finland were already practiced in using it without injury to themselves or others.

Developing the fundamental skills of scientific investigation begins early, as you can’t whittle a stick without observing the effects of the knife. If the blade is digging too deep, you “hypothesize” and alter the angle or reverse the stick to compensate for the direction of the grain. While the hypothesis in this case is non-verbal it nevertheless, builds a framework of shared understanding. Both religion and politics can be dangerous because they ask us to accept on “faith” that which is proposed by others, often for the purpose of manipulating us, rather than trusting us to build upon shared experience or offering the tools to do so.

Everything in life, from the simplest things to the most complex, offers the challenge of observation and interpretation. Both religion and science are perceived as theoretical abstractions when people, even from the youngest child, have the capacity to observe and reflect but are cut short from building a cosmology of understanding within their own lives and are filled instead by the conjectures formulated by others. And those conjectures are often designed to separate us from each other.

When the manual arts movement was launched in the U.S., there were two recognized fathers of the revolution. Calvin Woodward at Washington University and John Runkle at MIT were both math teachers who had noticed that as fewer of their students came from farms where they were involved directly in the observations and experience that farming offered, they were declining in the ease with which they understood math. Their remedy was to offer hands-on learning in shop classes to raise student capacities for abstract studies. The byproduct would be to build a framework of understanding just as had been described as Diesterweg earlier in the century and what would be described later as “scaffolding” by educational psychologist Jerome Bruner.

Charles H. Hamm, writing as an advocate for universal manual arts training in his book Mind and Hand, in 1886, describes these connections: “It is easy to juggle with words, to argue in a circle, to make the worse appear the better reason, and to reach false conclusions which wear a plausible aspect. But it is not so with things. If the cylinder is not tight, the steam engine is a lifeless mass of iron of no value whatever. A flaw in the wheel of the locomotive wrecks the train. Through a defective flue in the chimney the house is set on fire. A lie in the concrete is always hideous; like murder, it will out. Hence it is that the mind is liable to fall into grave errors until it is fortified by the wise counsel of the practical hand.”

In other words, to know truth, you must do something and test what we think we know. The “wise counsel of the practical hand,” is more needed now than ever before.

In the early days of the introduction of manual arts training in the U.S., many educators worried that taking time for it from busy schedules would retard academic studies, just as today Kindergarten (twisted from what Froebel had in mind) has become the new first grade in an ever increasing demand that children read and thus acquire knowledge third hand, while original shop classes and Kindergarten both emphasized first building knowledge from real life.

More recent research at Purdue (in 2009) illustrated how hands-on learning was superior to lecture and book-based learning for all students. The results were even more significant when gender and language barriers were considered. And so the question becomes, Can hands-on learning help to moderate some of the issues of polarization and tribalism currently plaguing our culture and politics?

Instead of trusting children to make observations based on experience and the use of their senses, we begin indoctrination at a very early age. We insist that children believe what they are told that comes second or third hand from others instead of providing means for them to discover and test truth firsthand. You will note the difference between first and second “hand” as the word hand is a direct reference to the means through which we acquire knowledge.

Of course, we can’t possibly learn everything from direct experience, as there’s a lot to know, but a basic structure of knowing that comes in the manner described by Diesterweg offers a foundation for discernment of truth. From the known to the unknown, from the easy to the more difficult, from the simple to the complex, and from the concrete to the abstract offers a view of the way knowledge and a sense of truth are constructed, built through the senses in response to observation and the encouragement to reflect. We all have hands, and common use of them begins to build a structure of shared understanding that has the power to remake the world in which we live. That’s probably why the Kaiser outlawed Froebel’s Kindergarten in 1851, and that’s exactly why we need a renewal of Froebel’s Kindergarten and universal manual arts education now.

Educators lost all interest in Manual Arts Education back when policy makers decided that we’d be a “service economy” in an “information age,” and we would leave making things to those countries that could make things cheap. Circumstance have forced policy makers to realize the lack of wisdom in this policy.

Personal and international tragedies mount in the name of religion and politics, and such abstractions cut short the building of necessary cosmologies within individuals. The rise of conspiracy theories, the hardening political rifts, the pervasive cynicism that grips the weary victims of culture wars and bloody wars all stem, at least in part, from our detachment from embodied sense making. People all over the world have been made gullible and too easily duped.

My simple hypothesis is that when students become inoculated against misinformation by becoming deeply engaged in doing real things, they build an understanding that’s based more on direct observation than on third-party information that was designed to deceive and control for malicious purposes as is already happening with AI.

Universal Manual Arts Education and restoring the original purpose of kindergarten, both aimed toward building a shared sense of community, can build intelligence, understanding, and community while also providing students with a better framework for discerning truth.

As a woodworker, retired from teaching wood shop, and the author of The Wisdom of Our Hands: Crafting, A Life I note that there’s a lot of work that must be done. But though the problems are vast, the remedy is at hand.

11 comments

Ronald Hansen

Thanks Doug, along with the other fine written contributions you have made, this commentary provides yet further reason and context for balancing the curriculum in public schools. My recent thought is that we (those of us who have technical thinking and problem solving skills) recognize that learning comes in many forms, each no more, or less, important than the other. Non academic and non-formal learning needs to be explored more fully by education policy makers. The adult education literature remains the best source for that analysis.

Mike Rodgers

Really interesting article. As an educator and administrator for 30+ years in private k-12 schools and private universities, I think you are entirely correct in your assessment of the value of manual arts in education. And as a hobbyist hand tool woodworker, I have been fascinated with the relatively recent renewal of the interest in the manual arts. I was interested in your politics and religion comments (my graduate degrees are in theology and political philosophy). I probably have a different slant on this very complex topic. But thank you for a very good article which I am passing on to my son who is the headmaster of a k-12 school and to the Dean of the school of education in my university.

Doug Stowe

Thanks for reading, commenting and passing the essay along. One of the things we learn in particular from woodworking is the value of forgiveness. We all make mistakes, and we learn through our own trial and error, to appreciate the efforts made by others, and to forgive when necessary.

Jukka Raulamo

Awesome essay. And great commets too. Greeting from Finland.

Phillip Wacker-Hoeflin

Back in the 1990’s, i worked on the technical staff at the school of communications at a Northeastern college. That was a time before the dawn of digital technologies in filmmaking. In their Film Production major, the second year was devoted to manual skills development. In the first semester, students were split into teams, all filming the same script. Positions of Director, Camera and Lighting, Sound Recordist, and Key Grip were rotated on each of four shoots. This was at the time when fim was still edited by hand, using manual tools and written documentation. The second semester entailed each student having to cut the footage from the previous semester from various shoots that would provide the greatest challenge in terms of aesthetically adhering to the script.

Years later, as we were converting our facilities to digital post-production, I had occasion to have many long research conversations with a Hollywood professional. One day he asked me about our program in great detail. When I finished he said, “That explains it. You know, it’s always easy to spot a graduate of your program. They are the only ones who carry on conversations with crew members outside of their own department.”

Sadly, I watched the curriculum change as digital technologies surplanted the traditional tools and methods, and saw that reputation melt away.

Frankie Flood

What a great article, Doug. I teach students in college how to create things. In my twenty fours years of teaching I have noticed that students from ten years ago were attending college with more capable hands and minds than they are today. I believe it was because of experiences they had working with their hands on the farm, at home, or in seventh grade woodshop courses (something that all Wisconsin students did in 7th grade). In-depth knowledge is scaffolded through experience and the scaffolding of today’s college student is sparse and does not have many levels. Your article outlines why I am experiencing and feeling this and I am thankful for your explanation.

However, I am hopeful when students return to my class for a second, third, or forth time because they want to experience the gratification of making something that is tangible and true. They also want to build off of what they have just learned. It is hard work to get up to speed (and try to catch up to where we should be) but some students see the value in having REAL experiences with all of their senses.

As always, thank you for putting thoughts and words to the things I’m feeling.

Doug Stowe

A college design teacher told me that many of her first year students were unpracticed in the use of scissors. But scissors, string and pocket knives were what we did before the internet robbed us of our time and skill.

Troutwaxer

This is a great article, and as one of the last members of my generation who was required to take a shop class to graduate high school, I can definitely see it!

Jeff Chimovitz

I just read todays Art Kusserow’s comment. All that I can add is “ditto.”

I started my 78th year yesterday. We’ll see if “not too late” to learn the wisdom of hands.

Doug Stowe

Hand skills are easier to develop at an early age, but it’s never too late for wisdom to take root.

Art Kusserow

Thank you for this piece, Doug In my high school years in suburban Pittsburgh, 1965-1970, our school year was divided into 3, 12-week terms. Every student was required to take 12 weeks of art, 12 weeks of music, and 12 weeks of either “shop” (for the boys) or “home economics” (for the girls.)

As a person with “two left hands,” I always marveled at my peers who could make razor sharp edge cuts with the band saw or create mortise and tenon joints with ease, whereas I could barely muster a passing competence with a simple drill press. But then again, I was in the “college track” and not expected to perform as well as those guys who were destined to be mechanics and carpenters. I wish I would have paid more attention to the wisdom of hands.

Comments are closed.