“There are some books you just like to read over and over again. Frog and Toad is like that,” my eight-year-old daughter told me the other night before I tucked her into bed. “Yes, it is,” I responded, remembering reading and rereading these books with my own mother. For those who haven’t heard of Frog and Toad, it’s a four-book series of heartwarming tales published in the 1970s. Written by Arnold Lobel, the award-winning children’s books revolve around the endearing friendship between two anthropomorphic male amphibians as they navigate various small adventures and uncover life lessons. One of my favorite stories in book two of the series, Frog and Toad Together (the sequel to Frog and Toad are Friends), is called “The List.” In the opening chapter, Toad meticulously outlines his daily agenda, marking off completed tasks such as having breakfast and dressing up. However, during a walk with Frog, a gust of wind snatches Toad’s list away, leaving him flustered as he struggles to recall his plans. Once twilight approaches, Frog wisely suggests it’s time to retire for the night. Toad suddenly brightens up, realizing that sleeping was indeed on his list. The two friends peacefully doze off on a rock, concluding their day. While Toad’s list is never found, all is well because the two have each other.

Perhaps, like me, reading this summary helped you breathe in a little deeper, as I often do when reading the series aloud with my children. The stories are gentle. Their calm, simple focus on easygoing friendship feels like a warm breeze that lulls one almost into a meditative state. For me, Frog and Toad reads like pastoral poetry of the highest sort. Thus, when Frog and Toad fall asleep together at the end of “The List,” to say there’s a lack of sexual tension not only would be an understatement but also a rather odd observation to make. Indeed, you might even be jarred a little reading this paragraph that begins describing an aspirational friendship in children’s literature and ends with mentioning sexual tension.

Yet if you Google “Frog and Toad,” as I did the other day when looking up the new Apple TV show based on the series, the first results that appear are about how this book, targeted for children 6-8 years old, is actually about a romantic relationship, not a friendship. Probably the most well-known of these pieces is a 2016 article in The New Yorker, titled “‘Frog and Toad’: An Amphibious Celebration of Same-Sex Love.” In it, Lobel’s daughter relates, “I’ve watched children grow up, and that whole drama that’s kind of the precursor to the hell of romance later in life—who is best friends with whom and who likes who when, and this person doesn’t like me now—it’s very painful, and I think that children really like to hear that this is not abnormal, that Frog and Toad go through these dramas every day.” I agree with her. These are the struggles of childhood, both from what I experienced as a child and adolescent, to what my daughter is experiencing now, and to what most others across the globe experience, too. Same-sex friendships, and yes, same sex-love one can term it, is part of the drama—and the solace—of much of childhood’s limited time span in our finite human lives.

This past fall, the girl who was my daughter’s best friend left her school, and she’s been absolutely devastated. She cries at night, missing recess playtimes, shared lunches, and whispered conversations in the school hallway. That she’s turned to the Frog and Toad books isn’t surprising for me. In the amphibians’ friendship, it makes sense that she’s found comfort and company; they likely remind her of the female friend she’s lost and the friendship she is mourning. While she has a brother around the same age as her, she’s always longed for a close female friend. This relationship’s subsequent attainment, and then loss in her child life, has felt significant.

As I’ve read the Frog and Toad books along with my daughter, I, too, have not only found comfort but also a renewed sense that, as children, shared, same-sex friendships take on a special meaning. Portrayals of friendship matter because they depict as important the actual social worlds children take part in day-to-day. Who doesn’t remember that feeling of having a childhood best friend or feeling isolated and hoping for one, just imagining how such a friendship might be? Frog and Toad’s adventures speak to both experiences, the friendship enjoyed and the one imagined. Moreover, that Frog and Toad are the same sex and take friendship seriously without questioning whether there is something sexual happening beneath the surface provides children with needed models about not only how to experience friendships in their present moment but also how to navigate the often difficult waters of friendship as adults.

At this point, it is notable to bring up the fact that studies bear out that same-sex friendships versus cross-sex friendships affect young people differently. When we sexualize same-sex friendships in books and stories meant for young audiences, like Frog and Toad, we do a disservice to young people who need good examples of how to confront and overcome obstacles in their social arena. Whereas relationships between romantic partners are often plagued with pronounced power differentials, as are boss-employee and parent-child relationships, friendships are most often fostered with others who are considered equal in status.

Children, because they need caring for by the nature of their dependency on adults in general, are almost always in power differential relationships with someone who wields more power than they do. Hence, friendships are an important way for children to learn about and practice how to interact with those who do not exercise control over them in some way. Most friendships in childhood (0-14) occur with those of the same sex because boys and girls alike choose these dynamics. They consider same-sex relationships as the most important to upholding their well-being and self-esteem—a fact likely because girls and boys see in same-sex friends someone who is most equal to them and who shares their lots in life. Further both sexes in this age group believe they find more support from same-sex friends than those of the opposite sex. As they go through coming-of-age experiences, they find intimacy with someone who is closest to being like them, including their biological sex. Until they enter high school, same-sex friendships define much of children’s and adolescents’ understanding of self and how they can, and ought to, interact with the larger world around them.

As a whole, children relate that the most important benefit of these friendships is a sense of intimacy and camaraderie. Intimacy is a feeling of connection and closeness, characterized by a willingness to share intellectual, spiritual, and emotional parts of one’s life. In same-sex childhood friendships, sexual sharing is not part of that equation. Rather, children with same-sex friends reveal details of their interior lives that they might hesitate to discuss with others who are not their direct peers (those who share similar biological and social experiences as they do and are thereby considered on equal footing with them). Intimacy between same-sex friends includes an inherent trust that a friendship can help when one experiences challenges outside of the friendship’s protective bubble. As a child, these challenges might include family issues, hormonal changes, school problems, and/or complicated social interactions. Thus, the intimacy one experiences with same-sex friends, and the comfort and self-confidence one obtains from these friendships, is integral to children’s development into whole human beings who understand who they are in relation to the constantly changing world around them.

Moreover, same-sex friendships in childhood help as one navigates adult relationships. Frog and Toad, while good friends, are dissimilar enough to sometimes experience social friction. Frog is more carefree and fun-loving, while Toad is more serious and cautious. Those of us who are adults understand that while our friends’ biology may be the same, oftentimes our predilections are not. Like Frog and Toad, we need each other not only to understand ourselves better but also to understand those who are different from us. Finer distinctions about who we are and how we can best interact with others come to light when we are with those who are most like us biologically and socially.

Another one of my favorite Frog and Toad stories is “Alone.” In it, Toad becomes sad because his friend wants some time without him, time simply to think and be alone. Frog responds to his friend’s sense that he has been slighted, explaining that he doesn’t dislike Toad or spending time with him. Rather, he simply also enjoys solitude and contemplation. “I wanted to be alone,” Frog explains to his upset friend, adding: “I wanted to think about how fine everything is.” Who hasn’t been in a friendship when we have wanted more from that friend than he or she was willing or able to give at that time? Similarly, who hasn’t had a friend who wants more from us than we would like to give or were able to give at the time? In “Alone,” Toad learns from his friend the value of contemplation and curiosity, neither of which he considered important until he discovered his friend’s unexpected personality traits that differed from his own. Intimacy led the two to communicate openly about their personalities, which led them to evolve (or metamorphosize we might say in their case), in their friendship and understanding of self and other.

That Frog and Toad learn from each other’s different personality traits, grow from them, practice forgiveness, and stay friends despite their differences is perhaps a lesson our highly charged world could learn from today. The more we view same-sex friendships through a hyper-sexualized lens, the more we risk losing the learning that occurs when we discover how different from us even our outwardly most similar friends are. Learning about and appreciating diversity often begins from that space of intimacy that same-sex friendship yields.

With this said, Toad’s feeling of being alone, without its attendant social resolution with Frog, is one most adults today share. Adult friendships in the United States are currently undergoing rapid decline. In fact, The United States Surgeon General has even said that we are now in “a public health crisis of loneliness, isolation, and lack of connection.” Young women post-pandemic reported that quarantine and social isolation affected their friendships negatively in startling ways. Almost 60% of women surveyed between 18 and 29 years old said they are no longer in contact with friends they had prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: 16% of those respondents said they had lost contact entirely with the majority of their friends during the pandemic. Young men now overwhelmingly rely on their parents more than their friends for intimacy and support, eschewing peer relationships for those that are unequal. When we sexualize relationship models like Frog and Toad, friendship intimacy becomes intermixed with sexual intimacy. As a result, children and adults alike may feel they can be less open in their conversations with same-sex friends. Not only might they worry about something they’ve said being misconstrued by their friend—making that single relationship more complicated—but the public also scrutinizes same-sex friendships in ways that make enjoying them more difficult.

Pop star Taylor Swift, for instance, is often spotted by the paparazzi holding hands with her female friends. While she has articulated publicly that she is not in a sexual relationship with any of them, her relationships with her same-sex friends are still construed sexually by those outside of the relationships. It is possible to interpret this intentional misreading of her friendships as shaming her for enjoying the benefits of same-sex friendship intimacy, intimacy that is distinct from cross-sex friendships and romantic partner relationships. The sexes experience the world differently and ought to be able to share intimate details with someone of the same sex, knowing that the way they experience and label that relationship will be respected. In hopping quickly to contemplating Frog and Toad in the bedroom rather than appreciating their shared actions and interests like gardening, we fail to recognize that friendship in and of itself deserves particular esteem—for children and adults. We contribute to the loneliness epidemic if we don’t value friendship for what it is, a relationship without sexual tension—and I suggest one without the power differential that often goes along with cross-sex friendships and relationships because of our society’s unequal gender stratifications.

Here, I bring in another one of my favorite children’s books that centers on same-sex friendship. Set in the late nineteenth-century, L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables series presents readers with a girl, Anne, who famously calls her friend Diana Barry, “a bosom friend,” someone with whom she shares the most intimate details of her life—its happenings and her emotional and spiritual ideas. These come from her heart and soul, or as she terms it in physical terms, her bosom. Whereas Diana is practical, Anne is imaginative. Akin to Frog and Toad, they learn and grow from their relationship with each other. Probably not surprising to readers of this article thus far, my daughter’s favorite read-aloud story right now is the Anne series. She’s not quite old enough to read it on her own, but she loves the social goings-on in Avonlea, dreaming of a dress with puff sleeves and a friendship group like the one in the book. I dreamt of both, too, at her age. The romance in the story with Gilbert Blythe took back burner for me but reappeared as something more important to the story, and my reading and reaction to it, as I grew older and entered a different stage in my life. With this in mind, Anne and Diana’s friendship always served as a beacon, and my same-sex adult friends have often described ourselves along these lines; we’re “bosom friends,” we jest.

Like the Frog and Toad series, these books have been subject to rising scrutiny and a questioning of its protagonist’s same-sex friendship. Scholar Laura Robinson famously ascertained that Anne is romantically in love with Diana Barry. I perceive her assertion as downplaying the passionate—but nonsexual—friendship the two have for each other, a friendship that ought to be lauded in and of itself for its own benefits to the two girls experiencing it, absent of sexual desire, especially a desire never stated by them but interpreted by outsiders, decades after the books’ entrance into literary juvenilia.

This pattern of sexualizing children’s books about friendship is detrimental to healthy relationships between the sexes, relationships that are distinct and significant. Frog and Toad might ultimately decide to marry each other at some point, or they may choose another frog or toad. The stories never say because that is not their focus: their focus is friendship. Likewise, had Anne wanted to marry Diana, that, too, would have been that story’s focus. The authors, whether gay or lesbian themselves, wrote books that sustain their popularity in part because they depict the truth of friendship and what it means to young people. If we fail to recognize friendship for what it is, and for the role it plays in the maturation process of children and young adults, we lose out on a world that is diverse in the relationships it values, one where equal relationships are constantly subjected to the idea that perhaps we can destabilize them, focus on power dynamics, and strip away the intimacy they uphold.

In a culture that often expresses the need to let individuals label themselves and their relationships, we ought not label Frog and Toad as anything but what they are—friends—which is, after all, announced in the title of the first book, Frog and Toad are Friends. Their friendship is one not only worth celebrating but also emulating for the ideal it offers, an ideal that helps its readers mature into adult relationships in an adult world.

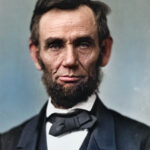

Image Credit: Thomas Fearnley, “Study of Water and Plants” (1837) via Wikimedia

1 comment

Shannon Hood

It’s saddening that an article like this is necessary, but I’m glad that this rebuttal was written (and well articulated). About halfway through, I wondered if you would bring up Anne, and sure enough, she was a perfect second witness to your argument. Again, thank you for writing this. Now I’m off to go write some letters to my far-away same-sex bosom friends. 😉

Comments are closed.