It is difficult to live through this era of American politics and not conclude that we are stuck inside a bad movie, a kind of Truman Show. Unlike Truman Show, however, we are not going to have someone pop out from behind the curtain and tell us it is all just a big gag. The Republicans, fresh from hosting Kid Rock and Hulk Hogan at their convention, have decided to run a comedy campaign, one loosely based on Idiocracy. The Democrats, meanwhile, have decided that the horror film known as Joe Biden for President is a complete flop and are going to go with the drama of Kamala Harris for President.

It would all be funny if the stakes weren’t so high. How did we end up in this mess? Enter Yuval Levin and his most recent book, American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation—And Could Again. In this book Levin has laid out both the best explanation and most able defense of the basic American political order I have ever read. Levin, who holds various titles at the American Enterprise Institute, soberly and lucidly explicates the basic theory that underlies our constitutional order and the various goods it produces. Levin’s work is not a legal treatise but a political one. One might say that it is a deft examination of the Madisonian character of the American regime. While Levin draws on many sources, James Madison plays an outsized role in driving the book’s argument.

It is commonplace to note that a “covenant” is a mutual sharing of persons while a “contract” is a mutual sharing of goods. Marriage, for example, is more a covenant than a contract. Levin’s choice of title, then, is notable. His central goal is to show how the Constitution helps create unity, which he cautions us not to be confused with unanimity. Levin is at pains to note that while we need not agree with one another, we do need to act together. As Levin puts it, the pathology of our times is not that we disagree—as disagreement is inevitable—but that we are unable to disagree well. Levin takes seriously the admonition of Madison in Federalist #10 that the seeds of faction are sown into the very nature of man. As long as human reason is fallible, we will come to different conclusions as to what the proper tax code looks like, how we should fund our schools, what is the right level of involvement of government in our health care system, etc. Good, smart, decent people will be found on all sides of these kinds of issues. “But how can people act together when they don’t think alike?” asks Levin. “That is the question that most troubled James Madison. It is the question that motivated a great deal of the work of the Philadelphia Convention. Indeed, it is one way to formulate the question to which the United States Constitution was, and remains, an answer.”

In political science nerd-talk this is what is called a collective action problem. How do we get people with different interests and opinions to work together for certain common purposes? This, says Levin drawing from Madison, is done through compromise, negotiation, and coalition-building. The way your average high schooler is taught about separation of powers (assuming they are taught anything) is that each branch has certain “checks” on the other two branches allowing for a “balance” of power amongst the three branches. The assumption is that tyranny comes from all power being in one hand, in this case one branch. By dividing power, then, and giving each branch some level of oversight over the other branches, we (hopefully) prevent tyranny.

This is not a false view of separation of powers, but it is radically incomplete. The goal of democratic politics, Levin teaches us, is not merely to record the sense of the people and translate that into policy, but to record the deliberative sense of the people. This requires arranging our political institutions in such a way as that the various interests of the people are represented and that we commit to action only after a consensus has been reached.

For example, the different modes of election of the elected parts of our government (i.e., everything but the courts) are a way of representing rival interests and promoting negotiation and compromise. We have a House elected by the people, in local districts, for a relatively short term. Before the 17th Amendment, we had a Senate elected by state legislatures, representing states, and for a relatively long term. We have a president elected by the people (sort of), representing a nation (sort of), for a medium term. What do we have here? Among these three institutions, we have entities that represent people, states, and then people again. Also represented are local, state, and national interests. Finally, we have represented short-, medium-, and long-term thinking. Madison’s (and Levin’s) theory of separation of powers is that any legislation that makes it through this system will be the result of give and take. Various interests will have been considered and mollified. Madison concludes in Federalist #51 that “seldom” will the community act in such a way that the minority must fear oppression from the majority. Why? Because the legislative process requires consideration of minority interests. In fact, even in a legislative loss, the minority can be assured that at least some of its interests have been included in the final bill.

This whole process is ugly but effective. It’s been said that the legislative process is like sausage: you might like the outcome, but you don’t want to see how it’s made. Levin demonstrates ably that in addition to protecting minority rights, surely an important good, this process produces democratic virtues. The necessity of talking to each other, of learning how to compromise with those with whom we negotiate, and the political necessity of virtues such as tolerance and forbearance that such a system relies upon, shapes the soul of the American citizenry. We get used to working with people with whom we disagree. “Competition is not the only way to deal with difference and division in our system, however. A second and equally crucial mode of turning disagreement into strength is negotiation. In key moments, our system forces differing interests and ambitions to deal with one another-often literally to make deals with one another.” We temper our passions, do not insist on “all or nothing,” and learn to live within limits.

This last lesson is important. In some ways the message of Levin’s book is that limits are a neglected but essential good in our political order. We cannot ask too much of our politics or our institutions. Politics is the balancing of various goods. “The Constitution does this… at the level of principle, embracing at once liberalism and republicanism, individualism and communitarianism, majoritarianism and the protection of minority rights, consolidation and decentralization. This makes the American system a scourge of fastidious political theorists but is also responsible for its extraordinary durability and for the dynamic character of the system, which is always answering its own excesses and seeking balance without ever settling down.”

After laying out some of this basic theory, Levin takes the reader through the American political institutions—namely federalism, congress, the presidency, the courts, and political parties—to demonstrate how the founders’ conception of these institutions contributes to unity. We have distorted the founding vision, Levin contests, by elevating efficiency, centralization, and a simplistic view of democracy that help generate the mess that is contemporary American politics.

Let us take the presidency as an example. Above I said that the president represented the nation, sort of. Let me explain the “sort of.” Levin argues, correctly, that the founders did not see the president as a representative. As stated, any citizenry is constituted by various competing interests. These interests might be geographic, economic, religious, or what have you. The wide diversity of a modern republic such as the United States cannot possibly be represented (re-presented) by one person. The president’s job is more circumspect, namely, to energetically execute the law.

Still, to the extent that the president is a representative, we must turn to the other “sort of” I used above. I said that the president was elected by the people, sort of. Of course, we use the Electoral College to elect the president. Granted, every state (and Washington, D.C.) now uses popular vote to determine that state’s electoral vote, even though the Constitution does not demand it. In effect, then, we have fifty-one popular elections for president. But why not just have one big popular election and avoid the contingency realized in 2000 and 2016 wherein a candidate can lose the popular vote but still become president by winning the electoral vote? Levin tells us. Although not quite operating as the founders envisioned, the Electoral College fulfills their goal of requiring presidents to gain office by appealing to various kinds of people in various geographies. The Electoral College gives candidates incentive to spend the most time in the most contested states, presumably the most moderate states. Instead of attempting to drive up large vote totals from their most loyal constituencies, as would likely happen with a national popular vote, the Electoral College encourages candidates to speak to people who aren’t completely on board as well as forcing them to assemble a geographically diverse constituency.

It is in defense of the Electoral College that political scientist Herbert Storing coined the term “simplistic democracy,” the view, as Storing wrote, “that government is good so far as it is responsive to popular wishes: the business of government is simply to do whatever the people want it to do” (emphasis in the original). Levin’s footnotes indicate that he is highly influenced by Storing as well as by one of Storing’s students, James Ceaser. It is Ceaser, hailed by The Atlantic in 2016 as the man who predicted it all, who wrote in his influential 1979 book Presidential Selection that in addition to recording the will of the people, which is surely a good, a democracy needs to minimize the harmful effects of ambition (essentially minimize demagoguery), promote able leaders (namely those skilled at the arts of compromise and consensus building that are a large part of democratic governance), and construct a system the people find legitimate. Our system is failing to deliver these additional goods. As well as describing what our constitutional order is supposed to do, Levin then diagnoses what has gone wrong.

Here let me modify an internet meme: however much you hate the Progressives, particularly Woodrow Wilson, it isn’t enough. At each turn, Wilson emerges like Grendel at Heorot to terrorize the American constitutional system.

Wilson rejected the political science of the American founding. The American founders, especially Madison, believed that man is self-interested. He is more than self-interested—Levin notes Madison’s various appeals to republican virtue—but he is at least self-interested. A sound democratic politics must take this into account. As Madison famously noted, an enlightened statesman will not always be at the helm. Wilson denied this. At the core of Wilsonian political science is the belief that a politics that rises above self-interest is possible.

Wilson’s first whack at the problem of interest was in his book Congressional Government, his doctoral thesis from Johns Hopkins. Wilson complained about the American Congress because he found its work too messy: beholden to too many interests, and its power too decentralized, with congressional committees and their chairmen holding considerable power. In Congressional Government he pined for something like the British parliamentary system in which power is centralized in the hands of one political party which controls both the legislative and executive branches, thus able to efficiently pass a definitive ideological program. Later conceding that America was unlikely to drastically modify its Constitution to allow for such reform, he turned his eyes to the presidency. In his later work, Constitutional Government in the United States, he described a nearly all-powerful presidency, one in which a Rousseau-like general will is personified in one man. He wrote:

The nation as a whole has chosen him, and is conscious that it has no other political spokesman. His is the only national voice in affairs. Let him once win the admiration and confidence of the country, and no other single force can withstand him, no combination of forces will easily overpower him. His position takes the imagination of the country. He is the representative of no constituency, but of the whole people. When he speaks in his true character, he speaks for no special interest. If he rightly interpret the national thought and boldly insist upon it, he is irresistible.

In class when I read this passage, I like to play Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” as a soundtrack as I think it captures the spirit of Wilson’s thought.

Levin convincingly shows that it is the political thought of Wilson and his fellow early-twentieth century Progressives that has distorted our constitutional vision. Wilson believed a conflict of interests is not inevitable, nor can the negotiations amongst those rival interests produce any good. He wanted unanimity.

Power in Congress has been centralized into leadership, achieving Wilson’s goal of weakening committees and eliminating healthy compromise. We have turned the presidency into a plebiscitary office, with policy being driven by the executive branch rather than through the deliberation of congress as the founders had assumed. Levin argues, “The modern administrative state appeals to many political activists precisely because it diminishes the need for bargaining and compromise.” The courts, with many justices influenced by Wilson’s theory of the “living constitution,” see themselves often as policy makers rather than neutral interpreters. Federalism is weakened by the Progressive commitment to centralization. After all, dealing with one government is so much easier than reckoning with the messiness of fifty vibrant state governments.

Perhaps worst of all, Wilson and the Progressives turned on political parties. As I have argued at length, we live with the irony that our politics are partisan not because our parties are too strong but because they are too weak. Wilson believed that parties were corrupted precisely because they were captives of “special interests.” Also, because political parties were based on large, carefully balanced coalitions, they were relatively non-ideological and resistant to radical change. Wilson was an advocate of what became known as the “responsible party model.” This idea of party, taken from parliamentary, multi-party systems, declared that parties should present a consistent, ideological program to the people. The people would then choose among various programs. Whichever party won would then have a mandate to govern and implement its program. Progressives also weakened parties by advocating for primary elections, making candidate selection plebiscitary rather than deliberative.

Levin writes that Progressive theorists

sought a politics in which different parties offered thoroughly distinct and comprehensive policy programs, the public selected among them on Election Day, and then the winning party would have essentially unlimited power to pursue its program until the public voted for someone else. The competition among factions in society would not be resolved by their bargaining within the institutions of government but by voters choosing among them at the ballot box and letting whichever won a majority deploy all the powers of government in the service of its vision.

Wilson’s “responsible parties would populate his more polarized and leadership-driven Congress and elevate his more policy-assertive president, who could serve as the focal point of popular will.”

What is the result? Our parties are now much more ideologically monochrome. The virtue of a strong two-party system is that each party is itself a coalition, a creation and expression of compromise and consensus. Ideological parties alienate those who aren’t completely with the program. This is perhaps one reason for the rise of the independent voter. Polarized parties contribute to a polarized politics. The other party believes nothing that I believe. There are no office holders in the other party who share any of my views. If the other side wins, therefore, my side suffers a complete loss and is shut out of governing. The whole ethos of the “responsible party” is against consensus building, that notion I indicated above that minorities can feel comfortable in political or policy losses because they will get at least a few wins in any legislation. But today it is all or nothing.

A plebiscitary selection system rewards politicians who are adept at getting attention and creating spectacle while punishing those who seek compromise and consensus. The latter kind of politicians are labeled sell-outs, unwilling to enter combat against the other side. Politics today is portrayed as a death match, a kind of Thunderdome where two parties enter but only one party leaves. While moderate, consensus building politicians are sidelined, the ideological, combative, and celebrity politician is promoted. Anything smacking of compromise is rejected as betrayal while the corridors of government become a venue for performance and attention-seeking rather than governing.

Such polarization was precisely what the Madisonian Constitution was designed to prevent and is an almost inevitable by-product of the Progressive reimagining of American politics. It has led to the disastrous results we see today. Levin writes, “Politics is where we decide how to act jointly. That’s not what enemies do. As Aristotle noted, ‘Enemies would not even want to go on a journey together.’ Abraham Lincoln was not being naïve when he insisted in his first inaugural address, ‘We are not enemies but friends, we must not be enemies.’” Lincoln could call people fomenting civil war his friends, but, sadly, we cannot do the same regarding people who have a different idea about sound immigration policy.

Levin concludes, “This puts us all at risk of losing our patience with normal political life. We now all too easily persuade ourselves that this moment, unlike past ones in our politics, is an emergency—that we are on the edge of an abyss so that the normal rules must be put aside, and the imperative to compromise and bargain must be suspended.” As J.R.R. Tolkien noted in one of his letters, “You can’t fight the Enemy with his own Ring without turning into the Enemy.”

We cannot give into the temptation of thinking that our times are so different that basic civility must be cast aside. Once we have done that, we are lost. Levin gives us some programmatic suggestions for returning, at least in part, back to the original covenant. His suggestions are sound. Still, perhaps it is up to each of us, in how we educate, how we vote, how we talk to our neighbors, to instantiate the virtues of compromise, forbearance, and toleration. Perhaps we can once again be one people, united in our disagreement. Yuval Levin’s book is an excellent start in that direction.

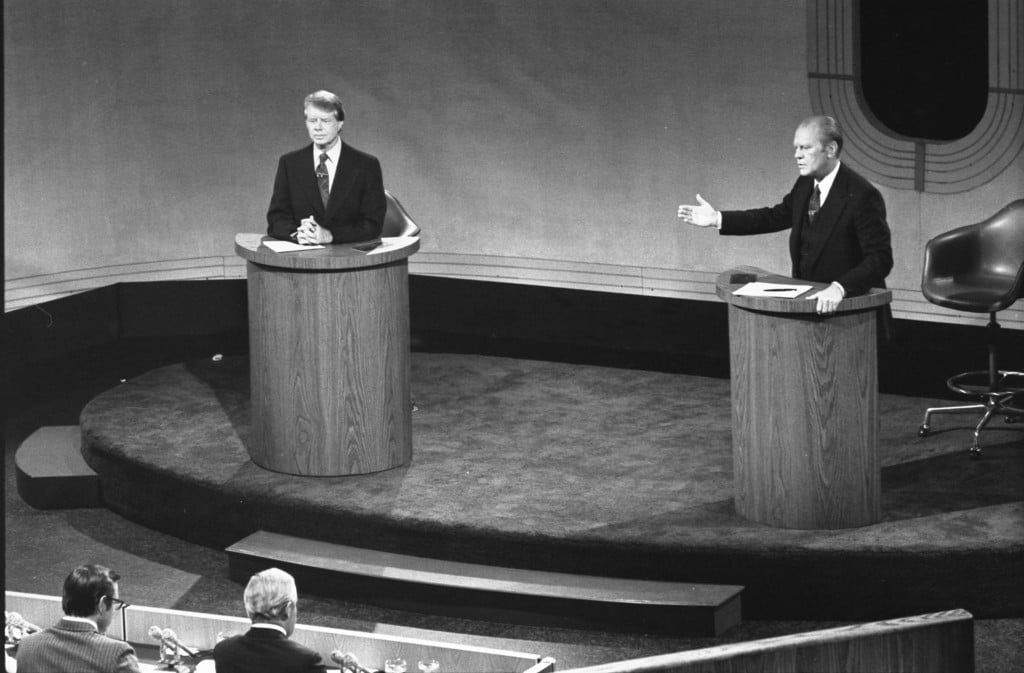

Image via Collections – GetArchive

2 comments

Curt Day

Two points need to be made here. The founding fathers were not the secular and political equivalents of the 12 Apostles, and the bipolar division in our nation is due to arrogance by those from all sides.

When the founding fathers talked about factions, and it wasn’t just Madison, they used the term faction as a pejorative for those with whom they politically disagreed. In particular, they used it on those, many of whom were veterans of the Revolutionary war, who expressed dissent with state governments over the economics of the times and participated in rebellions like Shays rebellion. In fact, in his letter to George Washington, Henry Knox denied that many who expressed dissent and/or participated in the rebellions were veterans.

As for arrogance serving as the foundation for the bipolar division in our nation, we need to consider the following Martin Luther King Jr. quote when he spoke against the Vietnam War:

‘The Western arrogance of feeling that it has everything to teach others and nothing to learn from them is not just.‘

If we replace the word ‘Western‘ with a fill-in-the-blank, we can see how many Republicans and Democrats, and perhaps we ourselves at times, are guilty of the same arrogance against which King warned us.

Ray Stevens

I read you all to see what the other side is doing.

One again I am distressed by what you say.

To wit: no one today ever mentions the name “Roosevelt”, the last of the three truly great President of this country (Washington, Lincoln and Roosevelt).

I grew up (in DC) during the war when Mr Roosevelt was President. He and with the cleaver aid of is wife managed to do everything your author is recommending when the depression,the destruction of middle America (which this site longs to return to) and the greatest and most dangerous war ever were offering to destroy us.

Also, I very much enjoyed your article and the thoughts of Mr. Levin.

R. Stevens

Comments are closed.