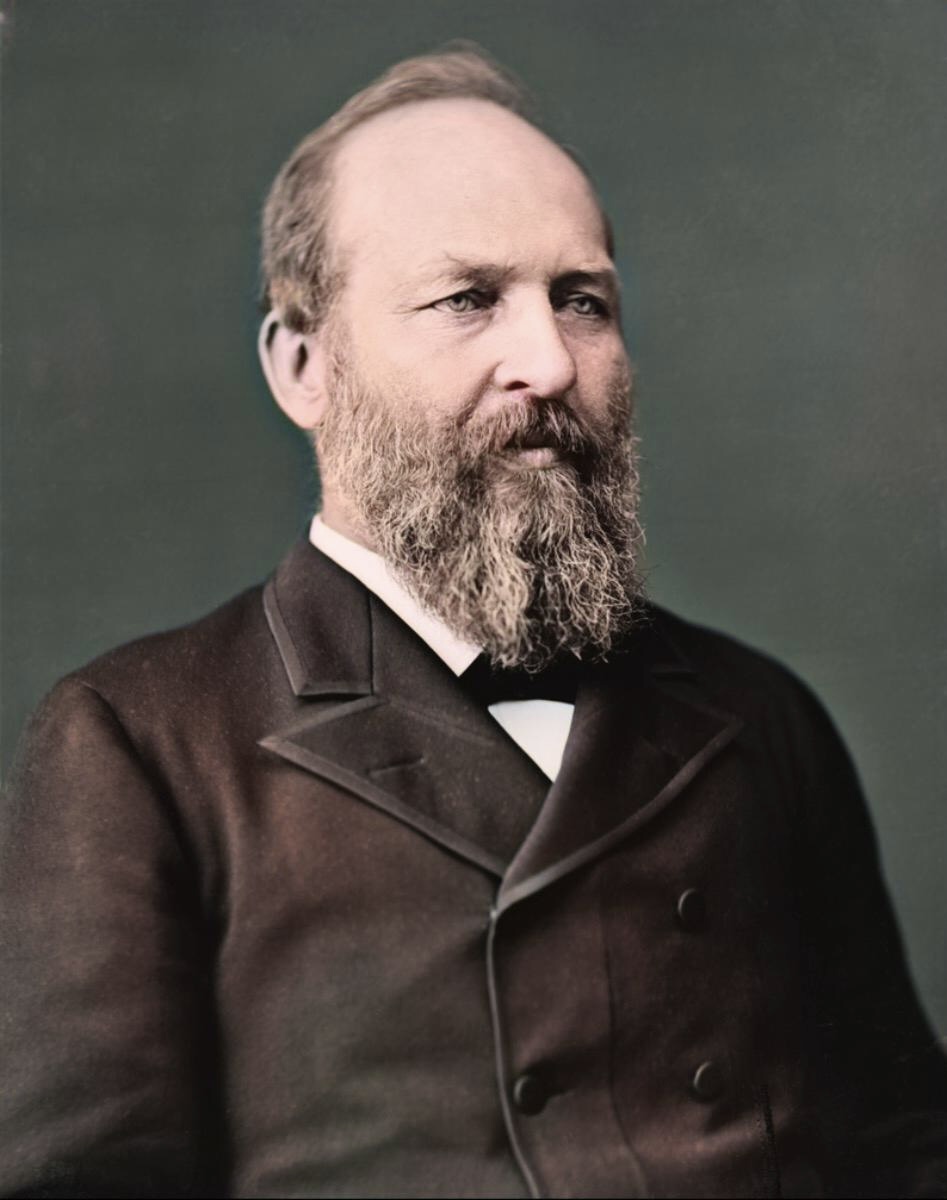

One of the more compelling political races in American history was the 1880 campaign by Ohio congressman James A. Garfield. After being nominated as the Republican candidate for that year’s election, the eventual 20th president of the United States returned home to his Mentor, Ohio farm to rest for his campaign. When he arrived at his one-hundred-and-fifty-acre property, he was met by a large number of well-wishers camped out on his front lawn. This was probably not a surprise to Garfield. He was a man that had developed deep roots in Ohio through his community involvement as a school teacher and administrator, as well as a soldier and politician. By the time Garfield returned home as a forty-nine-year-old Presidential nominee, a lifetime spent rooted in northern Ohio bore the fruit of a warm welcome home.

The story of Garfield’s campaign continued with the future president engaging supporters from his lawn. For much of the campaign, Garfield gave speeches, hosted events, and welcomed supporters from his large front porch. An estimated seventeen thousand citizens traveled to Ohio to hear from the presidential nominee in makeshift rallies set up on his property. In an era when presidential security was still very much in its infancy (Garfield would be assassinated in 1881 shortly after his presidency began), the front porch served as the natural place to connect with other citizens.

Community in Modernity

I have been thinking about Garfield’s campaign lately for a number of reasons. One reason is that it has been an election season. Every four years, I find it fascinating to see how candidates grapple with the best way to connect with Americans in a disconnected age. This campaign has featured the staged “community service” events that most elections feature, even if they do little to win supporters. Trump’s stint serving fries at McDonald’s to pre-selected customers adequately demonstrates the significant changes that have happened since 1880. While front-yard presidential campaigns are no longer practical, the contrast between Garfield’s community-based approach and today’s social media blitz is telling. As someone who came of age during the advent of social media, I have seen life quickly transition from the front of a home to the safety of backyards and the impersonal connections online. The effect of this transition on neighborhood community has been deadly.

In recent studies, the shift in neighborhood dynamics has been well documented. A study done by the Institute for Family Studies found that Americans today are about half as likely to spend time with their neighbors as they were fifty years ago. Other data back up these claims. The Pew Research Center found that a majority of Americans (57%) only know some of their neighbors. The demographics related to this question are also interesting. For those that are married, the likelihood of knowing their neighbors was much higher than their single and divorced counterparts. This is likely because those in more mobile situations are less likely to put in the costly work of making new friends where they live.

If neighborhood relationships are dwindling in our country, these numbers point to at least one important reason for this shift. Those who have lived in a neighborhood can attest to the fact that knowing those around us is difficult work. Americans today are more politically polarized and spend more time commuting to work and shuffling kids around to a variety of events than generations prior. Despite significant research indicating that Americans are more lonely than ever, most people are unable to unburden their schedules to do the difficult work of making friends. Rather than an indictment against individuals, these are signs that our culture has sold us an industrialized view of life. Productivity is how our lives are measured, and friendship is difficult to quantify.

A New Challenge

In addition to the larger social differences between Garfield’s campaign of 1880 and our own day, the issue has a more personal element for me. A year and a half ago, my family and I moved across town to a new neighborhood. It was a larger home for a good price, and it seemed like an easy decision at the time. Our old neighborhood, a collection of older homes situated in the middle of downtown Columbia, South Carolina was a complicated community. It was the kind of community that you want to leave until you are gone. The neighborhood schools were poor, the crime rate was high, and some of the houses were left to disintegrate on their own. This was not the whole story though. At its best, our neighborhood was a vibrant community of diverse characters who lived much of their home life situated on front porches or playing with children in their driveways. Due to a number of socioeconomic factors, time was a more abundant resource in this neighborhood.

If our old neighborhood was connected, the complexity sometimes made it a difficult existence. If a car was left unlocked by mistake at night, the next morning was usually begun by sorting through what was left of any belongings stored in the car. Most often the only thing taken was some change, but other times it was more personal belongings. In addition to the lack of car security, it was common for someone, typically in the throes of addiction, to ring the doorbell and ask for money. Next door lived a couple prone to existing as hermits who only emerged to flip off the neighborhood when folks walked too close to their driveway. Despite these challenges, my wife and I lived on a street with neighbors who knew the names of my children and had invested in our lives.

The new neighborhood we live in lacks the complexity of the old. Most of the families are middle class with manicured back lawns to retreat to after work is over. Community on weekends in our neighborhood is usually limited to waving at neighbors as they shuttle back and forth to sporting events and grocery stores. In many ways, it is a much more normal American experience than our old neighborhood offered. The messiness of different types of people existing together is gone. There is very little crime, and if a car door is left unlocked at night, it is rare to find something missing in the morning. If our old neighborhood had community but lacked a sense of safety, our new neighborhood is the reverse. There is safety, but community takes much more work. I now understand why Americans are so often lonely people.

A few weeks ago, I decided that I would no longer let my neighborhood skate by in its peacefully isolated existence. I told my wife, to her surprise, that I was going to organize a chili cook-off for the neighborhood. We set a date for late October and cleared our schedules that weekend. I printed out some flyers, and my daughter and I walked the neighborhood stuffing them in mailboxes and handing them to anyone that happened to be in their driveway. We endured more than a few bewildered looks as we walked towards them with flyers in hand. The resistance against disrupting isolation was palpable.

A couple weeks after handing out the flyers, I realized that only one person had contacted me about bringing chili. That person was the HOA president and was more community-minded than most. The hope was to connect by phone with neighbors and have each person donate ten dollars for a prize awarded for the best chili. I was discouraged as the phone didn’t ring and the few neighbors I saw in passing mentioned nothing of the event coming up. Despite not hearing from any contestants, my wife and I spent the Saturday of the cook-off putting out a table, buying some fall decorations, and making a couple batches of chili. Even if no one came, we were going to sit out front and show that we were committed to welcoming our neighbors, even if the community wasn’t interested.

By late afternoon, to my surprise, a steady stream of neighbors started to show up. Some of the families had young children like us, others were older couples and single people who seemed excited to meet the people that lived around them. The mood was festive, partly because of the cool fall weather and the fact that the South Carolina Gamecocks had beaten Oklahoma in football earlier in the day. For a couple of hours, our driveway was the center of activity as people tried each other’s chili, connected over small talk, and earnestly asked if we could do more events like this in the future. It was a great and surprising day, and I hope it is a precursor to more community being built in the future.

Changing the World on the Front Lawn

That late October day as we sat in our front lawn eating chili with our neighbors, I thought about Garfield and his 1880 campaign (I am a political nerd). While friendships can certainly exist in our workplaces, relationships that happen on front lawns and porches are different. The people who stopped by our home that day met a version of our family that was difficult to manufacture. The leaves were piled on the lawn waiting to be raked. The clutter in our garage was there for all to see. The neighbors were even able to meet my parents who swung by to say hello to their grandchildren. The front of our homes provide space for us to interact with more holistic versions of our neighbors.

In more recent years, I have come to believe that local community is one of the best antidotes to our social problems. Modern wisdom questions the use of social media and offers new laws to restrict hate speech and access to weapons, even while the families that live in shouting distance to us remain unknown. While government policy is important and commuting is often a necessary inconvenience, making time for our neighbors is an investment with a high return. Although the political views in our nation are polarized, it is much more difficult to hate someone from another political tribe if you know their children. Additionally, overly strong views on debatable policy are tempered when we are in relationship with reasonable folks on the other side. Tribal instincts are counteracted in neighborhoods because a relatively diverse group of people is inevitable.

Community is also a place where character is best formed and displayed. The election of 1880 was won by Garfield with two hundred and fourteen electoral college votes. Garfield was a man who never really wanted to be president and committed to serving only one term. Although he was shot less than a year into his presidency, it took Garfield eighty days to die from the wound the bullet inflicted. Much of the damage done to him was from doctors unaware of germ theory digging dirty hands and instruments into his body searching for the bullet. Like many figures from the late nineteenth century, Garfield has largely been forgotten. What is undisputed though, is that he was man of honor and integrity. Garfield was a man of faith who was converted at age eighteen and lived as a faithful Christian until the end. He was a public servant who pushed back against the corruption of the day and was invested in the community he was raised in. Garfield was known to preach in the Disciples of Christ church in the downtown of Mentor, Ohio and was well-liked and respected in northern Ohio. Perhaps his greatest legacy, however, is the front porch campaign he waged in the fall of 1880. Although he was running for national office, much of his message was made from his home as followers fanned out over his large front yard. Even today, the large home in the small town is a popular spot for tourists with political inclinations. Garfield’s campaign nicely points to the biblical advice not to “despise small beginnings.”

I am not sure if Garfield ever made chili for his supporters. The men and women who descended on his property were there to meet a future president. What Garfield understood, however, is that home is the best place to begin a movement. Regardless of what is happening in national politics, Americans are reeling from the effects of compounding generations of loneliness. People are waiting for a host to open up their yard and allow others to join them. While we face significant challenges to neighborly friendships, I believe that people really haven’t changed that much in the past one hundred and forty something years. If given the opportunity, people will come when someone is willing to issue an invitation. In an era when everyone is looking for a hack or guru to improve their lives, maybe a simple bowl of chili could be an answer to many of our problems.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

3 comments

Charles B

One lasting effect from the assassination of President Garfield was the Pendleton act, establishing ‘merit’ as a requirement for government employment rather than political appointment. This, because the man who killed Garfield was upset he wasn’t appointed to a government position.

We may soon see the end of the Pendleton Act.

More on the Pendleton Act (https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/pendleton-act#:~:text=Approved%20on%20January%2016%2C%201883,Act%20in%20January%20of%201883.)

Frank Filocomo

Beautiful post. Thank you for writing it!

David Naas

Amen.

Selah!

Comments are closed.