“The Virtues of Alasdair MacIntyre.” Brad East reminded me of this old essay that Stanley Hauerwas wrote reflecting on MacIntyre’s thought. It’s superb: “Few dispute that Alasdair MacIntyre is one of the most important philosophers of our time. That reputation, however, does him little good. It is as though, quite apart from the man, there exists a figure called Alasdair MacIntyre whose position you know whether or not you have read him—and whose name has become a specter that haunts all attempts to provide constructive moral and political responses to the challenge of modernity. The curious result is that MacIntyre’s work is often dismissed as too extreme to be taken seriously. In fact, MacIntyre’s work is extreme, but we live in extreme times.”

“There’s No Such Thing as a Free Nobel Prize.” Atar Hadari reviews The Letters of Seamus Heaney and shows how Heaney’s generosity and fame put an immense burden on his life: “The conflict between fame and private life, the tension between the preservation of the inner life that emits the poetry and the public life that elicits the reading and buying of that poetry, the ripples from the outside that touch the inner person and ripples of the inner person that affect everyone around him, all these are the themes of the book.”

“Irretrievable Eden.” Madeleine Austin reviews Outside The Gates of Eden, a new collection by the Shreveport poet David Middleton: “This is no mere collection of idyllic pastoral poems, as one might assume at first glance. Rather, true to its theme, the collection contends with the realities and mysteries of life post-Eden alongside more descriptive, pastoral poems of creation.”

“Alasdair MacIntyre, R.I.P.” Robert Wyllie recalls what it was like to read MacIntyre as an undergraduate, and he goes on to describe his experiences as a grad student when he got to know the man himself: “Students didn’t say ‘based’ back then, early in what we thought would be the Age of Obama, nor did they ask to be ‘redpilled.’ Still, I was fascinated by this philosopher with no time for trolley problems or rights talk, who brusquely changed the subject to character and “Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?” Like so many, I was more of a fan than a student.”

“Goodbye Oakland A’s. Hello Oakland Ballers.” Leighton Woodhouse visits the new baseball team in Oakland and describes the importance of a hometown team to the struggling city: “This is the appeal of the Ballers to Oakland fans: Unlike the A’s, the team is not trying to be somewhere else. As if to test their resolve, the city’s criminals have already put the team through the paces. Thieves have broken into two of the players’ cars and stolen a third. . . . Nevertheless, Freedman wants the Ballers to be “one of the big centers of gravity” in the city.”

“The Myth of Automated Learning.” Nicholas Carr describes the threat that AI tools pose to education: “Cheating is a symptom of a deeper, more insidious problem. The real threat AI poses to education isn’t that it encourages cheating. It’s that it discourages learning.”

“Don’t (Only) Blame Tech.” Nadya Williams reviews two books about technology, one in ancient Greece and one today: “When Mayor’s book was published in 2018, conversations about AI were in their infancy and the iPhone was just over a decade old. Now, however, the book offers essential food for thought for those worried about the escalating speed of technological developments and their indiscriminate availability to all, including children. Why? Because, as Mayor shows, visions of technology and artificial intelligence permeated Greek mythology. This ancient existence of something that we associate with modernity should give us pause.”

“MAGA’s Machiavelli: The Quiet Rise of Michael Anton.” Eli Lake profiles Anton’s thinking and career: “In this decade-old mini-scandal around the essay and its author, one finds the roots of a problem that plagues the country today. Yes, the ‘Flight 93’ essay in 2016 read to many (including me) like apocalyptic hyperbole. It was an extreme analysis that justified the violation of political norms to stop an existential threat. But in Chait’s and Kristol’s responses to ‘Flight 93,’ one finds a similar apocalyptic hyperbole. Comparing Anton to Schmitt is another way of saying the elected president is Hitler. In 2025, after the FBI’s meritless investigation into the Trump campaign’s phantom collusion with Russia, the purges and cancellations of the George Floyd summer, and the reckless federal and state prosecutions of Trump, even after he was his party’s nominee for 2024, the ‘Flight 93’ essay seems less extreme—almost prescient. Today, both parties accept their own version of Anton’s apocalyptic logic.”

“Review of A Commonwealth of Hope.” Philip D. Bunn reviews Michael Lamb’s new book on Augustine’s politics: “Lamb accuses these diverse receptors of Augustine of being like a man who looks too narrowly at a single part of a mosaic. By zooming in on merely a part of a beautiful whole, Augustine’s proponents and critics alike miss the mosaic for the tiles. At the root of Augustine’s theology and politics, Lamb argues, is a particular theological virtue: Hope.”

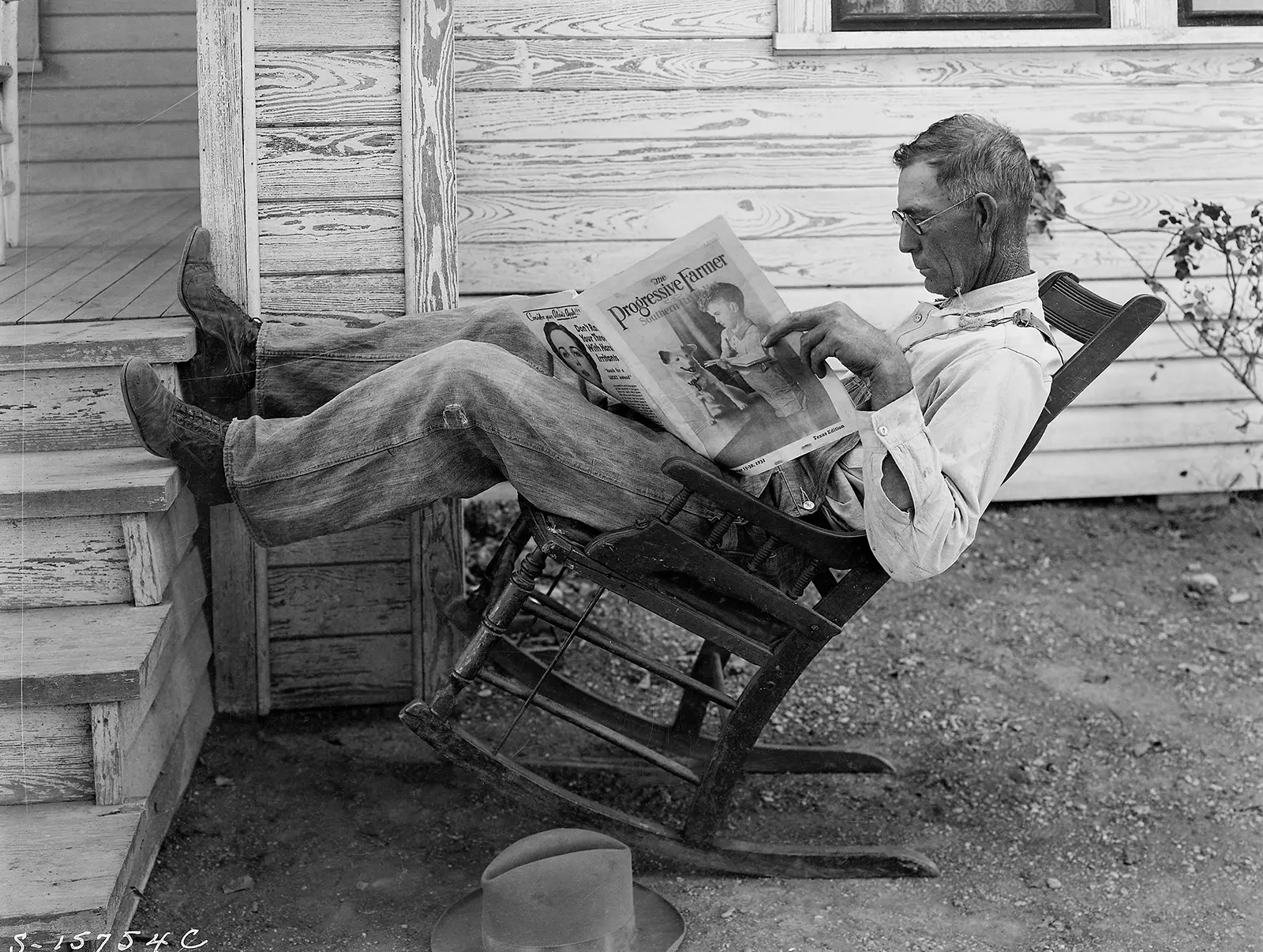

“Forgive Us Our Debts.” Casey Spinks defends the virtue of frugality, as long as it’s in the service of radical love: “Only a compelling understanding of the love present in frugality can open our eyes to a more charitable vision of the frugality that is such a great part of the American, and Protestant, tradition.”

“The Plusses and Minuses of Gioiatopia.” Alan Jacobs responds to Ted Gioia’s reflections on education at Oxford and AI: “And the kind of learning that Ted Gioia and I prize will still go on. However, it will primarily thrive outside the university system — as it did for many centuries before universities became as large a part of the social order as they are now.”