Music. From our mother’s steady heartbeat onward, sound and rhythm surround us. Music becomes the score of our life. In the mundane and the momentous, it reminds us of life’s meaning. It reminds us that there is more. In the holy and the common, for the young and the old, music lets loose the longing behind our heartbeats; it connects us to a world beyond ourselves, beyond even this world.

C. S. Lewis was drawn toward the infinite through music. As a young man, he heard Wagner’s Ring cycle, and his soul was stirred with longing. That longing ultimately led him to God. In De musica, St. Augustine of Hippo writes of how everything in the world, music included, gives us the opportunity to know God. For Lewis, music was a medium that drew him to God; it was “the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited” (Weight of Glory).

These snatches of a song we can barely hear, but nonetheless feel, surround us. Sound and tempo—in the form of frequencies—are present in every atom that make up everything. These resonant frequencies everywhere abounding are the work of a Great Composer. He has crafted not only matter, but also our melody and the symphony of history. From the very beginning, this Master has been making music. Mark Batterson, in his book All In, writes: “according to composer Leonard Bernstein, the best translation of Genesis 1:3 and several other verses in Genesis 1 is not ‘and God said’ [but rather] ‘and God sang.’ The Almighty sang every atom into existence, and every atom echoes that original melody sung in three-part harmony by the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” (118).

Composers are not the only ones to have picked up on the integral part music has played in our history. Psychiatrists and scientists uphold music’s precedence in our origins. In The Master and His Emissary, Iain McGilchrist argues that “language itself developed out of musical communication (a kind of singing)” (102). Citing anthropological and archaeological evidence to support his claim, McGilchrist posits the reason for music’s antecedence. “Ultimately,” he writes, “music is the communication of emotion, the most fundamental form of communication, which, in phylogeny as well as in ontogeny, came and comes first” (103).

In myth, too, music comes first, composing themes that shape individual and cultural stories. J.R.R. Tolkien’s history of Middle Earth in The Silmarillion beautifully blends song and emotion in the world’s creation. In his opening chapter, entitled The Ainulindalë (“Song of the Ainur”), Tolkien describes Middle Earth as being sung into existence. Ilúvatar, the all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good creator, made the Ainur, the holy ones, to be with him. He propounded “to them themes of music” which they learned and sang alone or in small groups (3). They grew in their ability to sing melodies and harmonies, and Ilúvatar called them to himself and commissioned them to “make in harmony together a great music” (3). From himself Ilúvatar kindled each Ainur with the Flame Imperishable, enabling them to ornament his theme with their own creative flourishes. The result was beautiful melodies that wove the world into being.

But one powerful Ainu, Melkor, became jealous of Ilúvatar’s composition and his place in it. “[A]s the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Melkor to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of Ilúvatar; for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself” (4). Instead of adorning Ilúvatar’s theme as his fellow Ainur had, he broke with it “and straightaway discord arose about him” (4). Most Ainur were dismayed by Melkor’s transgression, but Ilúvatar just listened to the turbulent clash of chaotic noise rising against his theme like a tempestuous storm. Then, with an almost imperceptible smile, Ilúvatar stood, raised his left hand, “and a new theme began amid the storm…and it gathered power and had new beauty” (4).

Melkor’s discord rose against it again, and Ilúvatar sternly raised his right hand, bringing forth a new theme “with power and profundity” (4). The themes of Melkor and Ilúvatar progressed side-by-side, and though Melkor attempted to drown the “deep and wide and beautiful” music with his cacophony, Ilúvatar the great composer wove Melkor’s discord into his own composition. Indeed, “it seemed that [Melkor’s] most triumphant notes were taken by the other and woven into its own solemn pattern” (5). Finally, with both hands uplifted, Ilúvatar arose and “in one chord, deeper than the abyss, higher than the Firmament, the music of creation ceased” (5). Then Ilúvatar spoke to the Ainur. And he addressed Melkor, saying “thou…shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined” (5). Then Ilúvatar showed them the world they had woven with their music, though it was but a part of what Ilúvatar had in store for Middle Earth.

Tolkien’s myth continues to resonate with modern readers because, like the Ainur, we crave harmony and resolution, and that is how the Ainulindalë ends: good wins, and discord is resolved. But beyond a cliché “happy ending,” there is a biological reason for our affinity for harmony. McGilchrist notes that “there are universal natural preferences at the physiological level for harmony over dissonance. Dissonance activates areas of the brain associated with noxious stimuli, and harmony areas associated with pleasurable experience” (419).

In life as in music, dissonance disrupts harmony, and we feel it. Life does not go the way we planned. Relationships rupture, calamity comes, those we love die. Sometimes our own desire to “increase the power and glory of the part assigned to [us]” brings discord. However it happens, harmony is broken. It is displaced by dissonance that often fuels unnerving anxiety and immobilizing fear. Yet life, like music, depends upon context. The discord of Melkor, when taken up into Ilúvatar’s theme, became something more wonderful than could have been imagined. So too, dissonance in our stories, when placed in the right context, can become more meaningful than we could have imagined.

Few composers rival J. S. Bach in his ability to introduce and resolve dissonance in musical compositions. At the time when he was composing, though, most of Bach’s contemporaries avoided dissonance. Harmony (especially in church music) was prized. Such harmony was found in music that was “consonant,” such as that produced by perfect fourths and perfect fifths. Such notions of “perfection” date back to Pythagoras, who applied math to music and, using ratios, uncovered basic harmonies such as the octave (2:1), the fifth (3:2), and the fourth (4:3). According to musician and author Hyperion Knight, Pythagoras and his followers “stopped at the seven white notes because going further required working with irrational numbers, which violated their pagan beliefs about how the universe was divinely ordered” (1) to sing the “Music of the Spheres.”

While later Christian composers allowed irrational numbers, they emphasized harmonies, as such music reflected the unity and harmony of the Trinity. Notes that were inharmonic, such as the tritone (a diminished or augmented tone), were avoided. The tritone created an unsettling sound evocative of evil and despair. It was so dissonant as to be dubbed “The Devil’s Interval” in medieval times. While it was not officially banned, the diabolus in musica was rarely used. Yet Bach frequently used tritones and other forms of dissonance such as suspension (holding out a consonant note after the harmony below it has moved on) and appoggiatura (adding a non-chord note to a melody which resolves into the chord note).

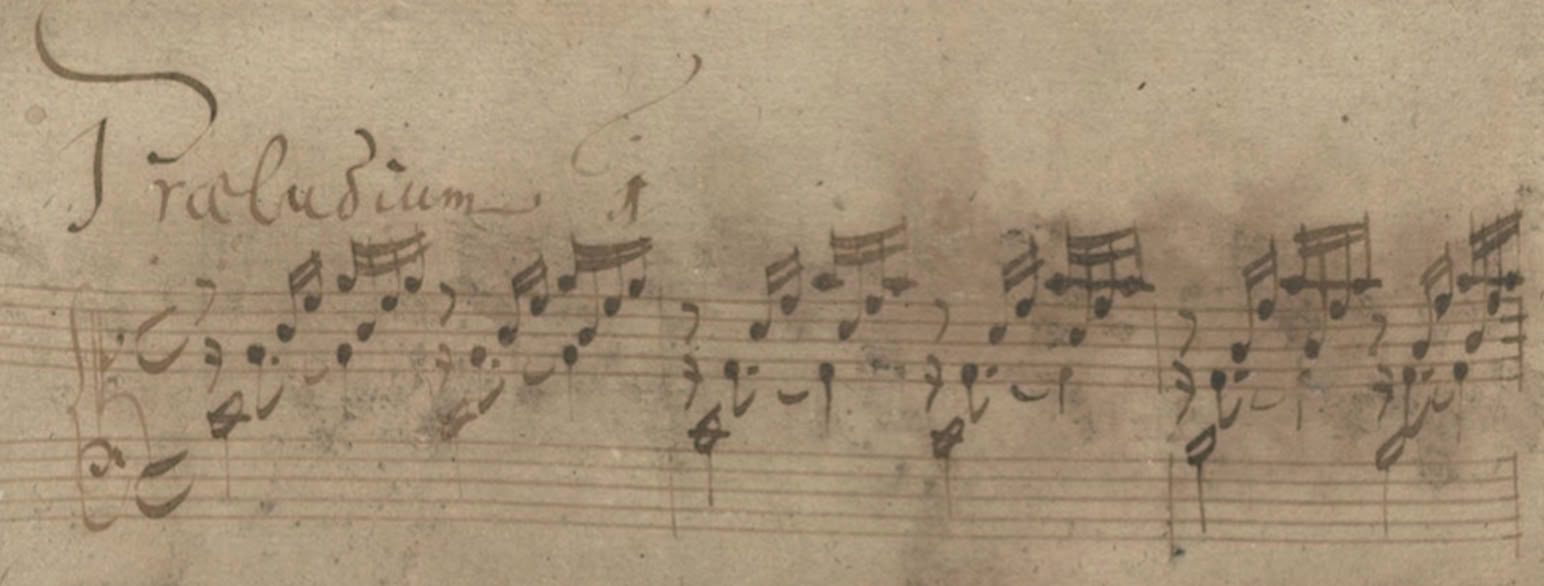

Bach’s use of dissonance was not his edgy way of undermining the ecclesiastical system; he had a deeply held reverence for God. In fact, before beginning any composition, he would scrawl J.J. (an abbreviation for the Latin phrase Jesu, Juva, meaning “Jesus, help”) at the top of his score. And once a piece was finished, he would pen the letters SDG (Soli Deo Gloria) as a finishing flourish. His work began with God’s help and was completed for God’s glory. As Mark Batterson writes in All In, “To Johann Sebastian Bach, the distinction between sacred and secular was a false dichotomy. All things were created by God and for God, no exceptions” (118). Bach understood that music—even, and maybe especially, with its passing dissonance—showcased the grandeur and goodness of God.

Because it is passing and is “introduced to be resolved” (McGilchrist, 420), dissonance actually heightens Bach’s musical themes. When taken up into his wider composition, discord becomes beautiful, because it is resolved into the harmony of the score (for examples, listen to his fugues in The Well-Tempered Clavier). The context of Bach’s dissonance—as a part of a beautiful whole—matters. “Music,” McGilchrist affirms, “is pure context, even if the context is silence” (420).

Even if the context is silence. Because sometimes it is. Sometimes in life, silence pervades our stories. The dissonance has passed, and we wait. We wait for resolution; we wait for harmony. With bated breath we listen for the next note, wondering “How will this theme, my story, end?”

“In harmony as elsewhere,” McGilchrist writes, “a relationship between expectation and delaying fulfillment is at the core of great art” (420). If poets and philosophers are right, and history is a symphony with God as its composer, then our lives are a part of His great work of art. “We are [God’s] workmanship” the Apostle Paul writes to the Ephesians, “created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (Ephesians 2:10, ESV). Because our melody is part of His masterful composition, we need not be fearful of dissonance. We have heard refrains of God’s song in history, in myth, and in our own lives, and we know that context matters. Though there may be dissonance or silence right now, we can be sure that the One who has written this composition will bring it to ultimate harmony. What we are enduring is passing, and it will be resolved into music more beautiful and breathtakingly satisfying than we can imagine, if we will only wait, and listen, and sing along.

What could it look like to sing our part in the harmony of God’s composition? To return to Tolkien, years untold after the world’s weaving in the Ainulindalë, an unassuming hobbit named Frodo embarks with his friends on a journey away from their peaceful home in the shire toward Mount Doom and their destiny. In a time of need, they are rescued by Tom Bombadil, a man older than the hills who sings songs that seem to be nonsense, but which rescue them from Old Man Willow’s clutches. He and his wife Goldberry invite the hobbits into their home and give them food and drink—what “seemed to be clear cold water, yet it went to their hearts like wine and set free their voices. The guests became suddenly aware that they were singing merrily, as if it was easier and more natural than talking” (The Lord of the Rings, 126, emphasis added).

C. R. Wiley, author of In the House of Tom Bombadil, wonders if Tom, being as old as he is, remembers and sings the songs of the Ainur that wove their world so many years before. Tom seems to be one of only a few who can hear these songs. Wiley asks: “If our world is also a work of art, then why can’t we hear music ringing in our ears the way that Tom and Goldberry seem to? Could it have something to do with how we perceive things? Are we even listening? Do we want to?” (57).

My hope is that we DO want to listen. For, as Wiley writes, “It is not only singing but listening that makes for harmony” (58). Yet what we listen to matters. The hobbits were entranced by the seductive singing of Old Man Willow and caught fast in his clutches. It was listening to old Tom Bombadil’s singing that brought them freedom, both from Old Man Willow’s clutches and to sing freely and easily.

“If Tolkien is saying something true about our world with his imaginary world,” Wiley writes, “then the music is still playing in our world, and what we need in our time is our hearing restored” (58). Like the humble hobbits of folklore and Bach of yore, may we have ears to hear this “Music of the Spheres,” hearts to receive its meaning, and voices to sing along in its song of creation, of whose consummation we play a part.

1 comment

Sarah

As I’ve considered listening and singing the song of creation more, the role of the Spirit has become undeniable. In the beginning, when the earth was yet formless and void, the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. Then God spoke, and the world sprang to life.

In the New Testament, when Jesus was baptized, he came out of the waters, the Spirit descended upon Him like a dove, God affirmed Him, and Jesus began his ministry of preaching the Good News of the Kingdom of God.

At Pentecost, people were cut to the heart by Peter’s preaching, and they asked what they should do. Peter replied: ““Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38, NIV). Elsewhere when people followed this command to repent and be baptized, the gift of the Holy Spirit is accompanied by speaking in tongues.

Being filled with the Holy Spirit is also associated with singing, as in Ephesians 5:18-19, where Paul admonishes his readers: “Do not get drunk on wine, which leads to debauchery. Instead, be filled with the Spirit, speaking to one another with psalms, hymns, and songs from the Spirit. Sing and make music from your heart to the Lord” (NIV).

The hobbits drank the water Tom gave them and were enabled to sing more easily than talk. I believe that, similarly, as we drink of the Spirit through repentance and baptism, we also are freed to hear and sing God’s song through the Holy Spirit.

Comments are closed.