Tonight the classic Capra film “It’s a Wonderful Life” is airing on network television, as good an occasion as any to re-publish here my reflections on the film. My take, in brief: George Bailey ruins the town he seems to save, and that saves him. All because he ignores the importance of front porches, and all they represent.

_____________

It’s a Destructive Life

Frank Capra’s “It’s A Wonderful Life” portrays the decent life of a small-town American, George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart), an everyman who saves his community from an evil Scrooge – Henry F. Potter (Lionel Barrymore) – and who only comes to realize his accomplishments by witnessing what terrors might have occurred had he never lived. George Bailey represents all that is good and decent about America: a family man beloved by his community for his kindness and generosity.

Yet, if there is a dark side of America, the film quite ably captures that aspect as well – and contrary to popular belief, it is found not solely in Mr. Potter. One sees a dark side represented by George Bailey himself: the optimist, the adventurer, the builder, the man who deeply hates the town that gives him sustenance, who craves nothing else but to get out of Bedford Falls and remake the world. Given its long-standing reputation as a nostalgic look at small-town life in the pre-war period, it is almost shocking to suggest that the film is one of the most potent, if unconscious critiques ever made of the American dream that was so often hatched in this small-town setting. For George Bailey, in fact, destroys the town that saves him in the end.

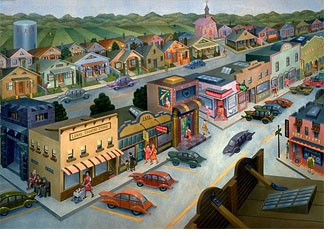

Undoubtedly viewers have come to adore this film in part because it portrays what Americans intuitively sense what they have lost. Among the film’s first scenes is the portrayal of an idyllic Bedford Falls covered in freshly fallen snow, people strolling on sidewalks, a few cars meandering slowly along the streets, numerous small stores stretching down each side of the tree-lined streets. It is an America increasingly unknown and unseen: wounded first by Woolworth, then K-Mart, then Wal-Mart; mercilessly bled by the automobile; drained of life by subdivisions, interstates, and the suburbs. Americans admire this movie because it portrays Mr. Gower’s drug store as a place to meet neighbors over a soda or an ice cream, not merely a place to be treated as a faceless consumer buying an endless variety of pain-killers; similarly, like Cheers, Martini’s bar is somewhere everybody knows your name, a place to spend a few minutes with friends after work before one walks home.

George Bailey hates this town. Even as a child, he wants to escape its limiting clutches, ideally to visit the distant and exotic locales vividly pictured in National Geographic. As he grows, his ambitions change in a significant direction: he craves “to build things, design new buildings, plan modern cities.” The modern city of his dreams is imagined in direct contrast to the enclosure of Bedford Falls: it is to be open, fast, glittering, kaleidoscopic. He craves “to shake off the dust of this crummy little town” to build “airfields, skyscrapers one hundred stories tall, bridges a mile long….” George represents the vision of post-war America: the ambition to alter the landscape so to accommodate modern life, to uproot nature and replace it with monuments of human accomplishment, to re-engineer life for mobility and swiftness, one unencumbered by permanence, one no longer limited to a moderate and comprehensible human scale.

George’s great dreams are thwarted by innumerable circumstances of fate and accident: most of the film portrays a re-telling of various episodes of George’s life for the benefit of a guardian angel – Clarence Oddbody (Henry Travers) – who will shortly be sent down to earth to attempt to save George during his greatest test. Despite all of George’s many attempts to leave the town of Bedford Falls – first as a young man with plans to travel to Europe, later to college, and then still later, and more modestly, to New York City, various intervening events constantly prevent George from even once leaving Bedford Falls. In the course of relating his life, however, we discover that George has helped innumerable people in the community over the years; these countless seemingly small interventions it will be later discovered have amounted to the salvation of the entire town. Despite George’s persistent desire to escape the limitations of life in Bedford Falls, George becomes a stalwart citizen of the town he otherwise claims to despise.

However, if George’s grandiose designs, first to become an explorer, and later to build new modern cities, are thwarted due to bad fortune, he does not cease to be ambitious, and does not abandon the dream of transforming America, even if his field of design is narrowed. Rather, his ambitions are channeled into the only available avenue that life and his position now offer: he creates not airfields nor skyscrapers nor modern cities, but remakes Bedford Falls itself. His efforts are portrayed as nothing less than noble: he creates “Bailey Park,” a modern subdivision of single-family houses, thus allowing hundreds of citizens of Bedford Falls to escape the greedy and malignant clutches of Mr. Potter, who gouges these families in the inferior rental slums of “Pottersville.” George’s efforts are portrayed as altogether praiseworthy, and it is right to side with him against the brutal and heartless greed of Potter. However, such sympathies serve also to obscure the nature of Bailey’s activities, and their ultimate consequences. In particular, it is worth observing the nature of “Bailey Park,” not merely by contrast to “Pottersville” – in comparison to which it is clearly superior – but also in contrast to downtown Bedford Falls, where it may not compare as favorably by some estimations.

Bedford Falls has an intimate town center, and blocks of houses with front porches where people leisurely sit and greet passerbys who constantly amble on the nearby sidewalks. Bedford Falls is a town with a deep sense of place and history. When George’s car crashes into a tree, the owner berates him for the gash he has made: “My great-grandfather planted this tree,” he says. He is the fourth generation to live in his house, and the tree’s presence serves as a living link to his ancestors, a symbol of the stories told about the dead to the living and to the unborn.

It is especially worth noting the significant role of the front porch in the course of the film. Numerous scenes take place in the intermediate space between home and street. While apparently serving as a backdrop for the more obvious action on the screen, it is worth pausing to consider the contributions, even “role,” of the porch in the underlying assumptions about a way of life that Bedford Falls permits. In a discerning essay entitled “From Porch to Patio,” Richard H. Thomas notes that the front porch – built in part for functional purposes, especially in order to provide an outdoor space that could be used to cool off during the summer – also served a host of social functions as well: a place of “trivial greetings,” a spot from which an owner could invite a passerby to stop for conversation in an informal setting, a space where “courting” could take place within earshot of parents or the elderly could take in the sights and sounds of passing life around them, the porch “facilitated and symbolized a set of social relationships and the strong bond of community feeling which people during the nineteenth century supposed was the way God intended life to be lived.”

By contrast, Bailey Park has no trees, no sidewalks, and no porches. It is a modern subdivision: the trees have been plowed under to make room for wide streets and large yards with garages. Compared to Bedford Falls – which is always filled with strolling people – the development is empty, devoid of human presence. The residents of this modern development are presumably hidden behind the doors of their modern houses, or, if outside, relaxing in back on their patios. The absence of front porches suggests an alternative conception of life that will govern Bailey Park – life is to be led in private, not in the intermediate public spaces in front that link the street to the home. One doubts that anyone will live in these houses for four generations, much less one. The absence of informal human interaction in Bailey Park stands in gross contrast to the vibrancy of Bedford Falls.

The patio – successor to the front porch – embodies as many implicit assumptions about how life is to be led as the porch. Thomas notes the move from urban centers into suburban enclaves in the years following World War II led to the creation of “bedroom communities” in which one did not know one’s neighbors and where frequent turn-over made such stable community relationships unlikely, where privacy and safety were dual concerns leading to the creation of the “patio” space behind the house, most often at the expense of a porch in the front. As Thomas contrasts the two, “the patio is an extension of the house, but far less public than the porch. It was easy to greet a stranger from the porch but exceedingly difficult to do so from the backyard patio…. The old cliché says, ‘A man’s home is his castle. If this be true, the nineteenth-century porch was a drawbridge across which many passed in their daily lives. The modern patio is in many ways a closed courtyard that suggests that the king and his family are tired of the world and seek only the companionship for their immediate family or peers.”

Bailey Park is not simply a community that will grow to have a similar form of life and communal interaction as Bedford Falls; instead, George Bailey’s grand social experiment in progressive living represents a fundamental break from the way of life in Bedford Falls, from a stable and interactive community to a more nuclear and private collection of households who will find in Bailey Park shelter but little else in common.

We also learn something far more sinister about Bailey Park toward the end of the film. George contemplates suicide after his Uncle has misplaced $8,000 and George comes under a cloud of suspicion. At this point the recounting of George’s life for the benefit of Clarence the angel ends, and Clarence enters the action to dissuade George from taking his life. Inspired by George’s lament that it would have been better had he never lived, Clarence grants his wish – he shows what life in Bedford Falls would have been like without the existence of George Bailey. George’s many small and large acts of kindness are now seen in their cumulative effect. Particular lives are thoroughly ruined or lost in the absence of George’s efforts. Further, the entire town – now called “Pottersville” – is transformed into a seedy, corrupt city in the absence of George’s heroic resistance to Potter’s greediness.

Attempting to comprehend what has happened, and refusing to believe Clarence’s explanations, George attempts to retrace his steps. He recalls that this awful transformation first occurred when he was at Martini’s bar, and decides to seek out Martini at home. Martini, in the first reality, is one of the beneficiaries of George’s assistance when he is able to purchase a home in Bailey Park; however, in the alternate reality without George, of course the subdivision is never built. Still refusing to believe what has transpired, George makes his way through the forest where Bailey Park would have been, but instead ends in front of the town’s old cemetery outside town. Facing the old gravestones, Clarence asks, “Are you sure Martini’s house is here?” George is dumbfounded: “Yes, it should be.” George confirms a horrific suspicion: Bailey Park has been built atop the old cemetery. Not only does George raze the trees, but he commits an act of unspeakable sacrilege. He obliterates a sacred symbol of Bedford Fall’s connection with the past, the grave markers of the town’s ancestors. George Bailey’s vision of a modern America eliminates his links with his forebears, covers up the evidence of death, supplies people instead with private retreats of secluded isolation, and all at the expense of an intimate community, in life and in death.

George prays to Clarence to be returned to his previous life, to suffer the consequences of the seeming embezzlement, but to embrace “the wonderful life” he has lived, and has in turn created for others as well. His prayer granted, George returns home to find that a warrant for his arrest awaits him, as well as reporters poised to publicize his shame. However, his wife Mary has contacted those innumerable people whose lives George has touched to tell them of George’s plight. In one of the most moving scenes on film, George’s neighbors, friends and family come flocking to his house, each contributing what little they can to make up the deficit until a pile of money builds in front of George. Trust runs deep in such a stable community of long-standing relationships: as Uncle Billy exclaims amid the rush of contributors, “they didn’t ask any questions, George. They just heard you were in trouble, and they came from every direction.” George is saved from prison and obloquy, and Clarence earns the wings he has been awaiting.

Despite the charm of the ending, a nagging question lingers, especially when we consider that many of the neighbors who come to George’s rescue are ones who now live in Bailey Park. If the tight-knit community of Bedford Falls makes it possible for George to have built up long-standing trust and commitment with his neighbors over the years, such that they unquestioningly give him money despite the suspicion of embezzlement, will those people who have only known life in Bailey Park be likely to do the same for a neighbor who has hit upon hard times? What of the children of those families in Bailey Park, or George’s children as they move away from the small-town life of Bedford Falls? A deep irony pervades the film at the moment of it joyous conclusion: as the developer of an antiseptic suburban subdivision, George Bailey is saved through the kinds of relationships nourished in his town that will be undermined and even precluded in the anomic community he builds as an adult.

30 comments

Ronald Highsmith

I had not given any thought to the film “It’s a wonderful Life” in years. I can recall sitting on the front porch with friends and watching as the neighbors drove by and we would comment on whom it was and where they were coming from or going.

As for the front porch, for whatever reason we moved to the patio and the backyard

for our “Private” parties (although I don’t know what was private about them), since it seemed like the entire neighborhood was there.

I do remember going however going downtown with my mom, sister and brother on Saturdays and we would go shopping at Goldblatt’s, Woolworths, and W.T. Grants. A few years ago I returned to my hometown. Goldblatt’s, Woolworths and W.T. Grants were gone as were the Paramount and Parthenon theaters and what had taken there place, a mall with chain stores and state of the art movie theaters. I guess Bob (Robert Zimmerman) Dylan was correct, “These times the are a changing”!!!!

Jano

Folks, print out this essay. One of Patrick’s best. And then rent the film and compare and contrast the shots of the development, and those of the graveyard when he’s with angel Clarence. Note the identical tree, shot from different angles. Unforgettable once Patrick has pointed it out to you.

James Kabala

The “Is Bailey Park built over a cemetary?” theme must be hot right now, because it came up almost right away in a discussion of the movie at the site A.V. Club. Several interesting theories (supported by movie dialogue) were advanced.

http://www.avclub.com/articles/its-a-wonderful-life,36565/

Be warned that the unmoderated forum includes bad language and that the site elsewhere links to the vile Dan Savage.

Rob G

~~The cemetery is just a prop to some cheap sentimental moralism about how important poor old self-pitying George Bailey is.~~

and

~~Which reminds me … the “what if you were never born?” vision from the Christmas ghost is a pretty self-absorbed twist on the Dickensian, “what if you weren’t such a jerk?” vision that leads to actual self-reformation rather than self-adulation.~~

Hmmm, so it’s a sop to a man’s self-adulation to attempt to rescue him from suicide by showing him that he matters? Now that’s a strange reading. Must be a Calvinist thang.

And yes, Empedocles is right; we’ve all heard the quip “it seemed like a good idea at the time.”

Hans Noeldner

Does behavior follow habitat? Does habitat follow behavior? Of course both are true, but living with a focus on the latter gives us many more possibilities for living as an act of creation.

I am trying to convince nominally enlightened people in my village to begin occupying our community more and more often as human beings, and less and less often as motorists…and then let’s see what happens!

My suspicion is that the specific FORMS of the built environment will more or less automatically morph into the human scale if more humans occupy it. OK, some places don’t have front porches – put a gazebo in the front yard – or a canopy – or just put some chairs there.

Or sit on the front steps, like row house dwellers have done for generations. It’s the presence of humans that matters, not spindles and posts and fretwork.

JB

I think everyone one of you are still forgetting the entire point of the movie!!!

Sean Scallon

Let’s see, Potter’s slums or Bailey Park…boy a tough choice there. In Pottersville you won’t have running water or electricity and live no better than pigs and pay through the nose to do so do but at least you have a front porch where you and your neighbors can commiserate in the misery around you.

It’s a Wonder Life is a great film because it does say a lot about the American Dream and its contradictions but it would be a mistake to read too much into it. If I had argued to George Bailey that Bailey Park was creating a “car culture” that would have destroyed Main St. and led to a souless suburban life that would lead those in it into drugs and sexual infidelity, he would have looked at me like I was mad. He would have no idea what I was talking about. Such terms did not exist back then and no one at the time would have contemplated them at all. All George and the Bailey family were trying to do was help working class people live in descent homes, away from Potter’s industrial slums that housed earlier generations of working class citizens, largely immigrants like Mr. Martini, who probably worked in Potter’s factories in Bedford Falls.

What created suburbia, which in turn created interstate highways and shopping malls, was World War II. The techniques used to build airfields and ports and other such mass-scale construction projects for war were used to build subdivisions, four-lane highways to strip mine mountains and clear cut forests. Bailey Park was just a few homes here and a few homes there, it was hardly Orange County, Calf. Hell, Mr. Martini got to keep his family’s goat on the drive out to Bailey Park. Think the homeowner’s association would allow that today in the gated community? I think not.

The problem was not with Bailey family’s dreams of proving decent homes to working men. The problem was the American penchant of overdoing everything.

Jungle Cat

On graveyards: “Let the dead bury the dead”. It wasn’t George Bailey who said that.

Bryan

I enjoyed reading your post. In our family is a tradition to watch “It’s A Wonderful Life” around Christmas time.

Roger S.

Thanks for the analysis. One of the things that struck me the other night as I watched this movie for the upteenth time, were the scenes of city life depicted in Pottersville–the lights, the crowds, the sheer numbers gathered in Martini’s bar. Contrasted with Bedford Falls, it appears as though Pottersville would be prefered by modern city fathers.

Michael Z.

I am shocked at such an bizarre interpretation of this movie.

Most notable was his very uncharitable take of the graveyard scene. Maybe I am a strange person, but I have always seen the Dickens Christmas Carol reference in that scene. Both Scrooge and Bailey find themselves in a graveyard during their wanderings. Instead Deneen insists that this scene is proof that George Bailey is a terrible person who commits sacrilege in his headlong pursuit of an anti-community.

I am very disappointed at this article.

brierrabbit3030

Best thing you ever wrote, Mr Daneen. I PDF ed this one for my own inspiration.

John Willson

Here’s another way to look at it, guys. I’ve watched this movie since it came out (how old ARE you, anyhow, said a wonderful little girl when she heard me say that I had seen Jackie Robinson play in his first season) and still watch it every so often and have never thought of it as anything much more than Jimmy Stewart at his sentimental best (he has other bests). Ward Bond is the ideal cop, of course, and probably all angels are stupid and all bankers evil. I still watch another Capra film, about the idiot Mr. Smith, every so often, because I like cynics turning around when almost none of them do. But let’s not make “It’s a Wonderful Life” into either a Front Porch or not a front porch. There’s no community in the film, either way you take it. It’s like “Nobody’s Fool,” a great flick about how an individual “makes a difference”–that is, if he’s Jimmy Stewart or Paul Newman. “The Best Years of Our Lives” took all the awards in 1946, and most people thought it fit in the same general mold. Watch it–it’s a great movie, and like the others above is about what Robert Nisbet called “the loose individual.”

D.W. Sabin

Russell,

If the sole reason for the suburban project was simply to make sure “more people had houses”, I think that the indiscriminate, ad hoc , consumptive nature of it could have been less damaging. No, it is well beyond getting more people houses. It was an experiment in modernity…the type which bypassed urbanity , that general hotbed of dissent and developed a mobile service worker…a resident of the globe and therefor a resident of nowhere. Suburbia must be viewed hand in hand with the globalist project. This project gleaned many benefits but if we cannot come to our senses and realize that our moral senses have been outpaced by our technological abilities…as well as our economic “sciences”…too far outpaced, we are doomed to the last phase of the Globalist Walk down a Primrose Path: Exhaustion……and impoverishment on all fronts….for the majority and a Gated Community, heavily defended for the minority…..hardly a “project for Democracy” whether they sentimentally intend it or not.

When we lost touch with knowledge related to how things are created, we lost touch with the feedback loops of a healthy social intercourse. The fact that much of the built landscape of the last 50 years (not all but the normative of sprawl) coincides with a swoon into the idea of a “service economy” is no coincidence. People who do not know how things are made or where they come from begin to not care about how things are made nor that place from which they come. They inhabit a simulacrum and while they retain the authentic faculties of a thinking person, the faculties tying them to the planet they live upon and the people they cohabit with begin to atrophy. Mesh this with a relentless and increasing fantasy life and a primary role as spectator and you arrive at a kind of able factotum whose spiritual essence will be but another function of the State.

Personally, I think Capra liked telling sentimental stories and he did it well and often used metaphor but I doubt there was much metaphor in IAWL beyond the now prosaic communal realities of the film’s era. Call me impervious. When it was made, not even the Cold War had begun to wreak its ultimate emotional havoc on the species. Dubai was a clutch of mud fishing huts enjoying the lethargic pleasures of obscurity and its economic underwriter Abu Dhabi was an even more remote redoubt of Bedouin on the edge of the Empty Quarter.

Caleb Stegall

Russell, neither. I just recalled it as another interesting application of IAWL to contemporary issues. Ross, as is typical, pulled his punches in an effort to preserve a happy middle, but his piece is hardly pure praise of Bailey. The piece is titled “Not So Wonderful Anymore.”

Russell Arben Fox

Caleb, I just got around to reading that link you put up: it’s Ross Douthat, praising George Bailey on essentially the same terms that Patrick weighs his accomplishment as being a tragically ironic one. Says Ross: yes, suburbia destroyed the front porches, but it did so in the name of making certain more people had houses, period. Did you put that link for ironic reasons yourself, or are you embracing Douthat’s analysis?

Bob Cheeks

I was going to pick a fight over Pat’s comments about the ‘front porch’ but there’s no way I can get around the fact that he’s right. I dunno, I suppose civility or politeness required the invitation to “sit a spell”, and then, on the part of the visitor, the obligation to accept the neighborly invite, to sit on your neighbor’s porch and talk.

Perhaps, inherently we understood that the porch provided the place for us to be who we are as a family, as a person, as a neighborhood.

And, on that porch on 7th street I sat and listened as my old man and Ray Copenhaver, smoking unfiltered Camel cigarettes and drinking Rolling Rock beer, shared war stories and hunting stories and stories of their childhood days; when my Irish-Catholic mother made peace with our Nazarene neighbors, the Knotts; when the Jones girls would come home from college wearing their saddle shoes and regal us with stories of Picksburgh or Ohio University and my mother as proud of those girls as if they were her own. And on and on.

Back then you needed a porch to have a home, maybe you still do?

Caleb Stegall

Carl, I think you give Capra way too much credit. I imagine that scene was played much more straight forwardly: i.e., without Bailey, the guy is dead, with Bailey, he has a house. There is zero acknowledgement of anything worthwhile about the cemetery, and zero self-consciousness of anything worthwhile having been lost in the creation of Bailey Park. That’s my recollection at any rate. I didn’t read Patrick as arguing that the film makers were intentionally recognizing Bailey’s folly, but maybe he was. Patrick?

Actually, come to think on it, it was Bailey’s brother’s grave that he stumbles upon, right? The angel tells him since he wasn’t there to save his brother from drowning, his brother wasn’t there to save all the soldiers in WWII. The cemetery is just a prop to some cheap sentimental moralism about how important poor old self-pitying George Bailey is.

Which reminds me … the “what if you were never born?” vision from the Christmas ghost is a pretty self-absorbed twist on the Dickensian, “what if you weren’t such a jerk?” vision that leads to actual self-reformation rather than self-adulation.

Carl Scott

Empedocles is right.

And Caleb, IAWL cannot be entirely propoganda for the Fair Housing Act, that is, not entirely friendly propoganda given its semi-esoteric bite, if Patrick is right about the graveyard scene. And what other interp could that scene be given?

But your points about urban problems being imported by IAWL to a small-town context seem useful.

D.W. Sabin

That “intermediate space between home and street” has become a tag team of the automobile and the Television, a kind of roving fort ably confirming one of my favorite Nathan Bedford Forest quotations: “Them who gits thar the fastest with the mostest, wins.”

Suburbia is many things but at basis , it is simply a vessel that contains a type of humanity that embraces the material over virtually everything else, ensuring that the material: our singular object, will continue to degrade , successfully complicating our yearnings into a kind of unsatisfied want.

Caleb Stegall

Quoting Carlson from above link:

“Let me explain this in still another way: according to Sterlieb and Hughes, not only had Federal housing policy ceased to sustain family life; it had now become an engine disrupting families! Divorce was good for business. A broken family would need two or even three dwellings, where merely one before had sufficed. The regulators and the regulated kept the housing industry afloat by undermining the very social institution they had once claimed to serve. Federal regulators showed their hand by easing mortgage eligibility standards for non-family borrowers and offering direct subsidies that reduced the real costs of creating two households out of one. Other direct and indirect subsidies encouraged home ownership among the unmarried by substituting government help for the economic gains (such as economies of scale) provided by marriage and family living. Through this veiled sacrifice of the family, the real estate and residential construction industries gained another two or three decades of prosperity, while the Federal government gained a burgeoning number of “non-family households” (8 million in 1960; 27 million in 1990) that would have more “needs” and be far more dependent on government “services” than the semi-autonomous families they had displaced. In sum, “social regulation” of housing in favor of families had been turned upside down: in the 1970’s and 1980’s, family break-up rather than family formation proved to be more lucrative and useful, and that is what your government delivered.”

Caleb Stegall

The biggest problem with the movie is that it imports urban problems into a rural/small-town context. Tenement housing was an urban problem and Potter is an urban villian. Here is Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives describing urban tenements and a real life Potter in NYC in 1890:

“Blind Man’s Alley bears its name for a reason. Until little more than a year ago its dark burrows harbored a colony of blind beggars, tenants of a blind landlord, old Daniel Murphy, whom every child in the ward knows, if he never heard of the President of the United States. “Old Dan” made a big fortune–he told me once four hundred thousand dollars– out of his alley and the surrounding tenements, only to grow blind himself in extreme old age, sharing in the end the chief hardship of the wretched beings whose lot he had stubbornly refused to better that he might increase his wealth. Even when the Board of Health at last compelled him to repair and clean up the worst of the old buildings, under threat of driving out the tenants and locking the doors behind them, the work was accomplished against the old man’s angry protests. He appeared in person before the Board to argue his case, and his argument was characteristic. “I have made my will,” he said. “My monument stands waiting for me in Calvary. I stand on the very brink of the grave, blind and helpless, and now (here the pathos of the appeal was swept under in a burst of angry indignation) do you want me to build and get skinned, skinned? These people are not fit to live in a nice house. Let them go where they can, and let my house stand.” In spite of the genuine anguish of the appeal, it was downright amusing to find that his anger was provoked less by the anticipated waste of luxury on his tenants than by distrust of his own kind, the builder. He knew intuitively what to expect. The result showed that Mr. Murphy had gauged his tenants correctly.”

IAWL was propaganda for what became Truman’s Fair Housing Act, which arguably wrecked rural and small town America (not to mention the cities).

Here is FPRs own Allan Carlson making the argument:

http://www.profam.org/pub/fia/fia_1407.htm

Caleb Stegall

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/10/10/AR2008101002267.html

Empedocles

I’ll just add that it is only with hindsight that we see how the post war housing development ruined community. I don’t think anyone moving into one at the time could foresee how they were going to alter the fabric of America and lead to the nightmare of sprawl we have today. It is curious that we never see Potter’s tenements. I’m sure the intended audience of the film was all to familiar with what they were like and in comparison Bailey Park seemed ideal.

Russell Arben Fox

Bailey’s problem is one that afflicts so much contemporary liberalism–he’s a mixture of Porcher and Proggie, but he has no real loyalty to or understanding of the first–his dreams and his ideology even incline him against it.

I can go along with this reading, Carl; thanks for contributing it. I suppose part of my resistance to Patrick’s original piece is that I’m in the same place you identify George Bailey as being in: I’m part Porcher (that is, I have communitarian and/or conservative and/or localist sympathies), but I’m also unable–perhaps for reasons of temperament, perhaps because of my unwillingness to turn away too much from the material goods of modernity, perhaps due to some other cause entirely–to conceive of the pursuit of communitarian goods without significant “Progressive” compromises with the market, mass society, and the state. The truth is, I strongly suspect that, in the end, that’s the place where Patrick and most of the rest of us probably are too.

Carl Scott

And Russell, Patrick never denies that George Bailey is a Progressive suburb developer, and that there are genuinely good and necessary things about that adjective. I.e., I don’t think Patrick denies that life in Bailey Park might be better, all trade-offs weighed, than life in Potter’s tenements. How could he given the film’s affirmation of the good George Bailey has done for the folks who live there? Bailey’s problem is one that afflicts so much contemporary liberalism–he’s a mixture of Porcher and Proggie, but he has no real loyalty to or understanding of the first–his dreams and his ideology even incline him against it. I.e., he has no adequate account of his own instinctualy communitarian virtues, and so the God he has come to hardly believe in has to intervene.

Carl Scott

Folks, print out this essay. One of Patrick’s best. And then rent the film and compare and contrast the shots of the development, and those of the graveyard when he’s with angel Clarence. Note the identical tree, shot from different angles. Unforgettable once Patrick has pointed it out to you.

Russell Arben Fox

Patrick, when I first read this piece of yours I thought you had an interesting insight, but stretched it to the point of tendentiousness; I’m afraid I still feel that way. Perhaps part of the problem is that, for once, you’re actually being a little more Marxist than me: you’re assuming that community virtues such as trust cannot possibly emerge in an “antiseptic suburban subdivision,” presumably because of the alienating socio-economic realities which such suburban developments involve, yet there is little evidence from the film that the demand for such developments as George Bailey commits himself to is being called into exist by such socio-economic realities. On the contrary, George pushes those developments in order to fight against said socio-economic realities: to make possible the preservation of family-supporting wages which will keep couples together, and to preserve the town’s tax base so as to fund its parks and schools, etc. Will the town be the same after George has done his work? Certainly not, and you’re right that something–literal front porches, perhaps–may be lost. It’s not a “conservative” movie, that’s for sure. But it is a profoundly communitarian one, and that is not to be dismissed.

Siarlys Jenkins

I didn’t see this film as a child, so stumbling upon it in my 40s I loved it. However, this analysis has been a real eye-opener. Of course if he had loaned people money to buy and fix up some of those beautiful old homes in Bedford Falls… but that is so 1990s. The value of those homes wasn’t recognized at the time, they were just out of date and in the way.

John Médaille

Thanks, Patrick. My wife loves this film, but its cloying quality always got on my nerves, but I was never sure quite why.

Comments are closed.