Saginaw, MI

This post is part of a series that will explore what prominent thinkers can teach us about today’s public multiversity, the modern university with its many colleges, departments, and other administrative units that play multiple functions and roles in our society.

In the past posts I have spoken about one of the obstacles that today’s multiversity confronts: the creation of the conditions of genuine learning. The vast creation of the mighty machinery of staff, administrators, and even faculty themselves have swollen to such proportions in the multiversity where the continuous contact between student and teacher is rare; and, if does transpire, it is often regulated by rules, regulations, and other forms of bureaucratic regimentation. What the multiversity needs to do is not dismantle itself but reorganize its various communities where they are decentralized and smaller in scale as the conditions of genuine learning demand. Of course, political, social, and economic demands will force compromises to be made, such as online remedial education, but these realities should not be the guiding principles for the multiversity to follow.

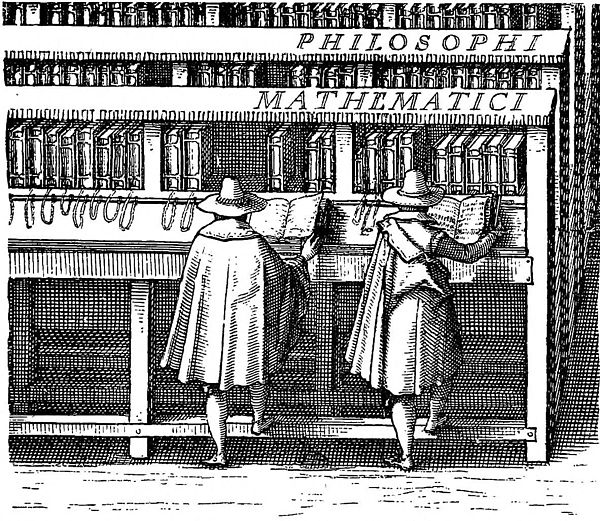

For this post I want to look at the danger of the sedimentation of learning that the multiversity faces today. The addition of knowledge to previous generations’ accomplishments, especially in the natural sciences and mathematics, is what we call progress and are properly proud of it. However, this achievement also leads to specialization, esotericism, and opaqueness, which plagues today’s multiversity as it did for European universities in the fifteenth century. How were these universities reformed from their narrow pedantry of medieval scholasticism? And what, if anything, can we learn from them for today’s multiversity?

The first wave of reform was a resurgent in the study of classical antiquity that initially started in Italy in the fifteenth century and then spread across Europe, a movement commonly known as Renaissance Humanism. From the study of the humanities – grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy – humanists hope that these new educated elites would be able to communicate with clarity and eloquence to persuade their fellow citizens to engage in civic life. Rhetoric was critical to humanist education, for it was seen as the primary vehicle for communication and debate, as opposed to logic which had devolved into Scholastic syllogism and disputations removed from common discourse. Thus, the older approaches to education were not eliminated by the humanists but modified in important ways that provided new information and methods to make learning relevant again in an accessible language for citizens to engage in the civic life of their communities.

The second wave of reform was the Protestant Reformation which continued the humanist orientation towards the study of the classics with the addition of emphasizing biblical texts to be studied in their original languages of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. Furthermore, Protestant colleges were initially autonomous in their governance and organization until they came under state control in the seventeenth century. But perhaps more importantly were the Protestant beliefs of the universal priesthood of believers, thereby encouraging everyone to become educated to read the Bible, and justification of faith through grace alone, which returns us to Augustine’s understanding of interiority rather than external authority as a place to discover truth. This emphasis on conscience led Protestants to believe that they had a responsibility to use their divinely-given faculties, including the power of reason, to explore God’s creation in responsible and sustainable ways. The Protestant Reformation therefore laid the groundwork for the democratization of education and the development of nature for the material betterment of human life.

The third wave of reform was the Catholic Reformation as a response to the Protestant one with the proper training of religious officers instituted and returning religious orders back to their spiritual foundation, emphasizing a devotional and personal relationship with God. At the Council of Trent (1545-63), the Catholic Church reaffirmed its sacredness of its rituals and beliefs and commissioned a catechism that would serve as the authoritative Church teaching. The organization of religious institutions was tightened, disciplined improved, and bishops were given more power to supervise religious life in their dioceses. At the same time, the Catholic Reformation addressed the criticisms of Protestants by improving the education and training of priests, permitting the creation of new religious orders attuned to the spiritual mission of Christ, and promoted mysticism and baroque art as pathways towards God. Thus, the Catholic Reformation returned to its original mission of cultivating a personal relationship with God with greater discipline and efficiency in a renewed culture life of mysticism and art.

Like its European predecessor, the multiversity has become intellectually incoherent with certain disciplines making tremendous advances in knowledge and application and other fields just being cryptic and arcane. Even when breakthroughs are made in knowledge, whether solving Poincaré Conjecture or uncovering one of Aristophanes’ lost plays, the achievement is often so technical, difficult, and seemingly so irrelevant to the general public to take notice and care. In some ways, it is no different than figuring out how many angels can fit on the head of a pin. The advancement of knowledge in a specific field is for itself alone, since the multiversity has no unifying paradigm to make greater sense of its worth and its place in the general public. Specialization leads to specific results and a public outcome of opaqueness.

The multiversity must look back to its own past for ways to reform itself from this intellectual stratification if it wants to be perceived as an institution that contributes to the public good of society. Renaissance Humanism sought to move the university from purely intellectual contemplation to civic engagement; the Protestant Reformation emphasized individual conscience as the site of learning and demanded that everyone should be educated; and the Catholic Reformation sought for the Church to return to its original mission of having a personal encounter with truth in a reorganized institution that promoted a renewed cultural life. Although each of these reform movement accentuate different aspects of education, all of them recognized that institutions of education, whether the university or the church, required change in order to be relevant to people’s lives. The multiversity must also come to this same realization; otherwise, the predictions about the collapse and unsustainability of American higher education will come to fruition.

Like the Renaissance Humanist reform movement, the multiversity should adapt its curriculum in the hope of civic engagement or whatever mission or paradigm it decides to adopt for itself. This does not mean that older approaches to education are to be eliminated but modified and enlarged as the Renaissance Humanists did. Likewise, the Protestant Reformation’ mission to educate all people comports well with our democratic notion of an educated citizenship and our hope for material betterment in a responsible and sustainable way. Finally, the Catholic Reformation underscores the importance that the cultural life of the multiversity is critical for a revitalized education as well as the need of organizational efficiencies and remaining true to one’s original mission. These reform movements provide us possible models for the multiversity to make itself known not simply an economic, cultural, or political good but as a public one. A glance back to the past might provide us some new perspective of how to make the multiversity relevant to society once again.

Lee Trepanier is a Professor of Political Science at Saginaw Valley State University. More information about him can be found at http://svsu.academia.edu/LeeTrepanier.

1 comment

Comments are closed.