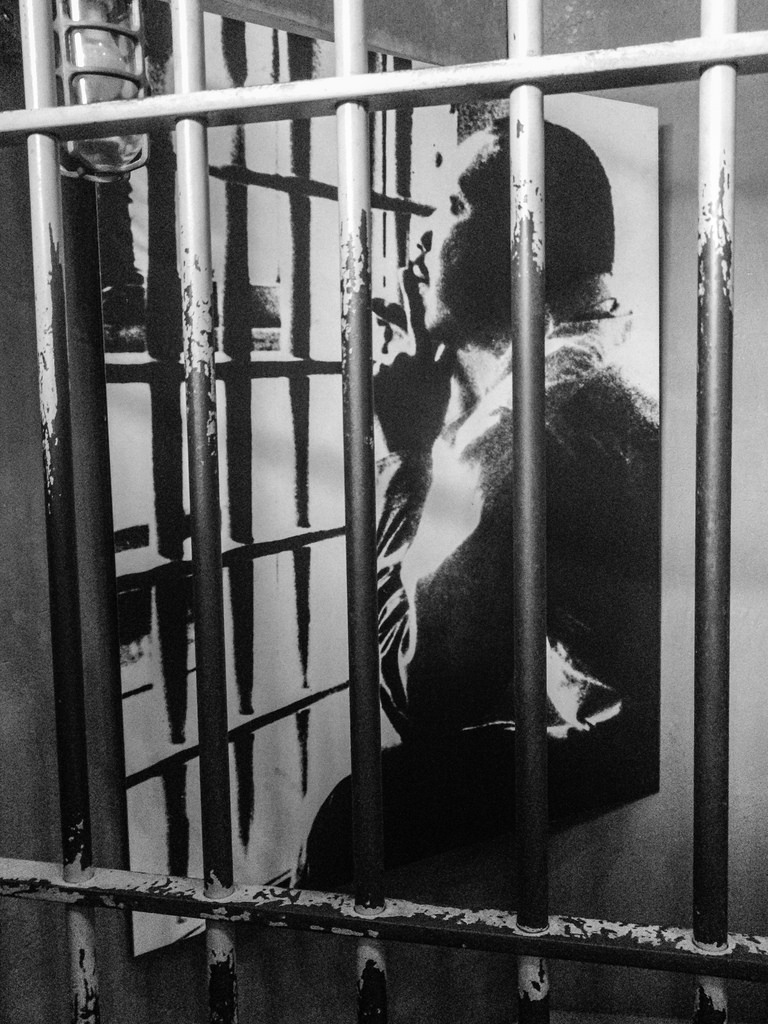

From a jail cell in Birmingham, Martin Luther King, Jr. charged us to acknowledge our “inescapable network of mutuality.” Fifty-five years later, our networks of mutuality remain inescapable. And they’re killing us.

Not King’s network—ours. The network he imagined possessed a liberating density, anchored by neighborliness, justice, civility. Our networks are lighter than the air our tweets fly through. King called us back to “great wells of democracy.” We call each other just to laugh out loud.

Yet for all of our unbearable lightness, our high-wired mutuality weighs heavily. There is the perhaps bearable social weight: Facebook updates, Youtube moments, Tumblr pix. There is the heavier civic weight: Brexit in Britain, bloodshed in Syria, mayhem in D.C. Then, the heavier yet personal weight: pleas from weary relatives, pressure from demanding employers, requests from distant friends. Our mutuality is evident. Our ability to live with it is not.

All networks are not equal. Mutuality is a fact that must be treated as an ideal: this was King’s point. Like all ideals, mutuality survives only by nurture; better, it survives within a habitat of nurture, within fleshly bonds of warmth, confrontation, and care. Our much vaunted mutuality certainly has a network. But it has no place to grow.

A day at the office: Sixty e-mails, thirty texts, ten phone calls, three meetings, two reports, all encased within streaming images, sounds, words.

A weekend at home: kids to a party, kids to a soccer game, a film, a trip for groceries, a trip to the mall, a football game, six hours of work, ninety minutes at the gym, all dotted with calls, notes, and texts.

Coffee with a friend? Maybe. A walk in the park? Monthly. Solitude by the river? Hardly.

Shoveling a neighbor’s snow? Maybe. Volunteering at the school? Monthly. Service at a shelter? Hardly.

A half-century ago, King sensed we were in “dire need of creative extremists,” extremists for “love, truth, and goodness.” He was distressed to find that in the midst of “a mighty struggle to rid our nation of racial and economic injustice” so many of those to whom he looked for aid were standing “on the sideline,” mumbling “pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities.”

Today electronically imported irrelevancies and trivialities are our daily bread, and we can’t see past our own struggles to keep our thousands of connections connected. We are extremists—extremists for connection. But connection for what?

For all their remarkable presence, our contemporary connections are failing us. We, the connected, are locked in networks of mutuality intricate beyond our ability to fathom. We look out and wonder if our connections will hold—or whether they will fail the good we know. Will the water stay pure, or will those connecting us to fuel befoul it? Will the financing remain available, or will those connecting us to our houses squander it?

Our connections are failing us. That’s why friends, despite all linguistic inflation to the contrary, are fewer. That’s why the days pass faster. That’s why our children are in danger, in so many ways.

King ended his letter by noting, in hope, that the “destiny” of his community, of his movement, was “tied up with the destiny of America.” He knew that someday we would come to see that “when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream.” “The goal of America is freedom,” he proclaimed. And everyone said Amen.

But freedom—another word for mutuality—is just one more ideal that requires nurture, a habitat, if you will. Create the habitat and the ideal may survive. But that may also mean going off the grid—and letting the network crash.

1 comment

David Naas

Recall the citizen band Radio craze of the ’70’s? It was supposed to promote communication, but as people discovered, it was a great way to hide behind a “handle” and present the uglier side of your self to the world. “Communicate”, it did not.

Forward to the many forms of media today, to instant news, to 24/7 adrenalin agitation , and the demands to respond to every tingle of smartphone notification. We are communicating ourselves to death. At least, to indifference and the numbness which comes from incessant bombardment of the senses.

There IS a solution, and one obvious to all. But, will we do it?

Comments are closed.