Most of the reactions to Billy Graham’s death yesterday have been, as you might expect, positive, which is welcome considering the way every day brings some news of how hypocritical evangelical voters were in turning out for Donald Trump. If evangelicalism can produce or stand for Billy Graham, how bad can it be? (So far, only David Hollinger decided to point out Graham’s weaknesses compared to the ethicist — that’s right, ethicist — who allowed Cold War hawks to feel mainly good about the military industrial complex. That leaves Reinhold Niebuhr as America’s favorite theologian with Graham running a distant second as everyone’s favorite evangelist.)

Christianity Today, the leading periodical for evangelical Protestantism and in which Graham played a significant role in founding, summarized Graham’s achievements this way:

“He became the friend and confidante of popes and presidents, queens and dictators, and yet, even in his 80s, he possesses the boyish charm and unprepossessing demeanor to communicate with the masses,” said Columbia University historian Randall Balmer.

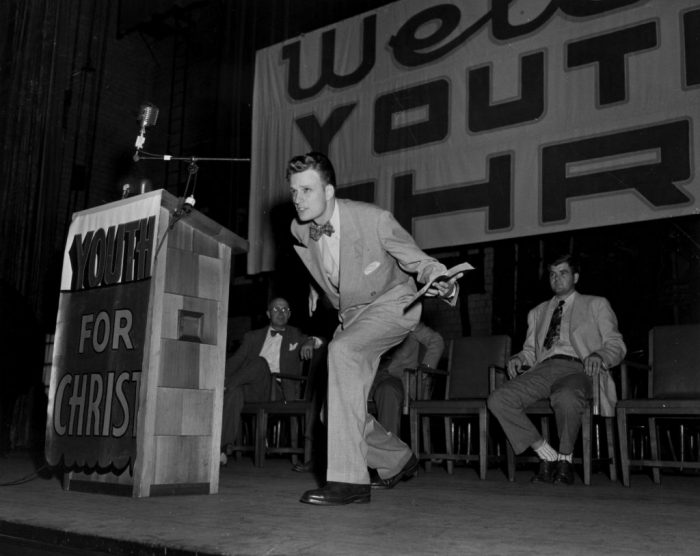

Billy Graham was born in 1918 in Charlotte, North Carolina, attended (briefly) Bob Jones College, graduating from Florida Bible Institute near Tampa, and Wheaton College in Illinois. He was ordained a minister in the Southern Baptist Church (1939) and pastored a small church in suburban Chicago and preached on a weekly radio program. In 1946 he became the first full-time staff member of Youth for Christ and launched his evangelistic campaigns. For four years (1948–1952) he also served as president of Northwestern Schools in Minneapolis. His 1949 evangelistic tent meetings in Los Angeles brought him to national attention, and his 1957 New York meetings, which filled Madison Square Garden for four months, established him as a major presence on the American religious scene.

Graham appeared regularly on the lists of “most admired” people. Between 1950 and 1990 Graham won a spot on the Gallup Organization’s “Most Admired” list more often than any other American. Ladies Home Journal once ranked him second only to God in the category of “achievements in religion.” He received both the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1983) and the Congressional Gold Medal (1996).

No matter what you make of Graham or his ministry, to be as likable and as popular as he was and for that long in the sphere of religion is a remarkable feat. John Paul II gained a lot of favor from people outside Roman Catholicism but even his tenure lasted only 25 years. Graham came onto the national scene around 1950 and stayed there until 2005, the time of his last — wait for it — “crusade.” (When the evangelist started conducting revivals in countries with a large Muslim presence, “crusades” became “missions,” which was a little before Wheaton College, Graham’s alma mater, changed its mascot from Crusaders to Thunder.)

Much of Graham’s appeal extends from his personal integrity and the lack of fund-raising pitches that afflict television and radio evangelists. Mike Pence recently made popular — with some derision to follow — the so-called Graham rule of never meeting one-on-one with a woman. (The Crown on Netflix bursts that bubble wonderfully with an episode devoted to Graham’s sessions with Queen Elizabeth.) A less noticed aspect of Graham’s character is his willingness to share his celebrity instead of making it a brand that he kept to himself and his organizations. He was the poster-boy for born-again Protestantism for the second half of the twentieth century not only because of the press coverage he attracted. Graham also served organizations other than his own. He was on the boards of Fuller Seminary, Gordon-Conwell Seminary, Wheaton College, worked among the founding editors of Christianity Today, and he lent his aid to numerous evangelical humanitarian and evangelistic agencies such as the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability, Greater Europe Mission, TransWorld Radio, World Vision, World Relief, and the National Association of Evangelicals. Today’s celebrity preachers generally keep their fame to themselves and the organizations that promote their appearances and books. (Even at The Gospel Coalition, an organization that fancies itself a return to a form of evangelicalism free from gaudy excesses, celebrities like John Piper and Tim Keller occasionally show up for institutional events, but maintain their own networks without explicit ties to the so-called alliance.) But Graham saw himself, if his actions are any indication, as part of a wider network of Protestants and did what he could to chip in. Of course, the transaction went both ways. Having Billy Graham on your board of trustees was a way of improving the status of your institution. But that did not appear to bother Graham or for that matter the people behind the scenes in Graham’s organization.

Some Protestants, myself among them, were not exactly wild about Graham’s ministry. Augustinians like those in Lutheran and Calvinist circles had no appreciation for Graham’s appeal to sinners to “decide” to let Jesus into their hearts. That form of address betrayed understandings of sinful human nature and divine sovereignty that were at odds with historic Protestantism. At the same time, Graham’s work, which was completely independent of a church or a communion, undermined implicitly the work of local pastors who were trying to the best of their abilities to evangelize the locals. Along would come Graham and all of a local pastor or priest’s endeavors seemed paltry by comparison. Here I’m reminded of what H. L. Mencken wrote about Billy Sunday and the kind of appeal a popular (and traveling) preacher had compared to the residential and denominational variety:

Even setting aside [Sunday’s] painstaking avoidance of anything suggesting clerical garb and his indulgence in obviously unclerical gyration on his sacred stump, he comes down so palpably to the level of his audience, both in the matter and the manner of his discourse, that he quickly disarms the old suspicion of the holy clerk and gets the discussion going on the familiar and easy terms of a debate in a barroom. The raciness of his slang is not the whole story by any means; his attitude of mind lies behind it, and is more important. . . . It is marked, above all, by a contemptuous disregard of the theoretical and mystifying; an angry casting aside of what may be called the ecclesiastical mask, an eagerness to reduce all the abstrusities of Christian theology to a few and simple and… self-evident propositions, a violent determination to make of religion a practical, an imminent, an everyday concern.

When Graham started out, he had more gyrations than he did later in his career when he became a fixture in American evangelicalism, even ascending to the status of statesman. But Mencken’s point about evangelicalism and the evangelists who benefited from it stands. Your average pastor cannot compete with the bells and whistles of a mass meeting and the publicity that surrounds it. Nor can your average minister disregard preaching through a book of the Bible or fashioning a homily based on the lectionary and situating that relatively learned speech into the fabric of a liturgy or order of service (for the Puritans out there). In other words, theology, church government, and convictions about worship constrain a pastor, not to mention the responsibilities of ministering over time to a variety of congregation or parish members in all manner of walks of life. Graham could simply give an invitation to receive Christ for seven nights in a row, with a different musical performance or celebrity interview, and then leave town. Your average pastor doesn’t have that pay grade. And if he is actually preparing his flock for the world to come (read death), then a religion that is “a practical, an imminent, an everyday concern” is not necessarily going to cut the Gordian Knot of how sinners become right with the sovereign Lord of the universe.

In other words, not all Protestants were thrilled by Graham’s ministry. In fact, going back to the revivals of the First and Second Great Pretty Good Awakenings, denominationally and theologically self-conscious Protestants (Anglican, Lutheran, and Reformed), have opposed mass revivalism because it undermines the work of the ordained ministry and the local church.

That leaves politics. For many observers of the 2016 presidential election, Graham represents the better side of evangelicalism, the time when born-again Protestants were not shills for the Republicans either aspiring to or living in the White House. The truth is, however, that Graham, as part of the post-World War II evangelical movement, made politics respectable. His version of conservative Protestantism rejected the negativity of fundamentalism and looked for a seat at the proverbial table. Graham and his peers did not engage in activism, though the evangelist did have to rely on his charm to avoid being forever tarnished by his friendship and support for Richard Nixon. In later years, he backed away from public appearances with presidents and presidential candidates, though as late as 2003 he and his son, Franklin, advertised support for George W. Bush and the war in Iraq. Even so, Graham was not the activist or political partisan that later blossomed into the Religious Right of Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson fame. What Graham and his generation of evangelicals did do was cultivate the idea that these Protestants, unlike the waffling and trendy mainline ones, needed to restore America to its Christian outlook. As such, evangelicals needed to be active in all aspects of American society. That kind of cultural engagement was a significant ingredient in the recipe that would in 1980 yield the evangelical embrace of the Republican Party.

All things considered, Graham appears to have been an admirable person who pursued his understanding of Christianity with remarkable vigor and consistency for over five decades. But for Christians who balk at the lowest (and sometimes schmaltziest) common denominator that animates evangelical Protestantism, Graham is one of those evangelists you cannot endorse even if you feel guilty about it.

2 comments

Udo Wald

As a believing pacifist Christian, Mr.Graham has always been the face of the anti-christ to me. His spawn, Franklin is doubling down on my perception.There never was a war that Billy didn’t like.

Jordan Smith

Thanks for this interesting perspective. I agree with much of it, although I wonder whether a balance is always needed between the folksy, Gospel of the people, and the “theoretical and ecclesiastical masks” of, say, Catholicism. Whenever I see one side of these debates deriding the other from (supposedly) higher moral ground I am left wondering how it is we always seem intent on ignoring the planks in our own eyes.

Comments are closed.