When I came across John Hockenberry’s essay, “Exile,” in the October edition of Harper’s Magazine, I had never heard of him. I still know little about him, though a simple Wikipedia glance tells me that Hockenberry has been paralyzed for his adult life, and that he worked as a journalist for ABC, NBC, and NPR. In 2017, the writer Suki Kim accused him of sexual harassment. Hockenberry’s essay also hints at other female accusers, but that’s as far as I got with researching his background, mostly because there are other channels for litigating what he did, and because I’m much more interested in engaging with what he said in the essay.

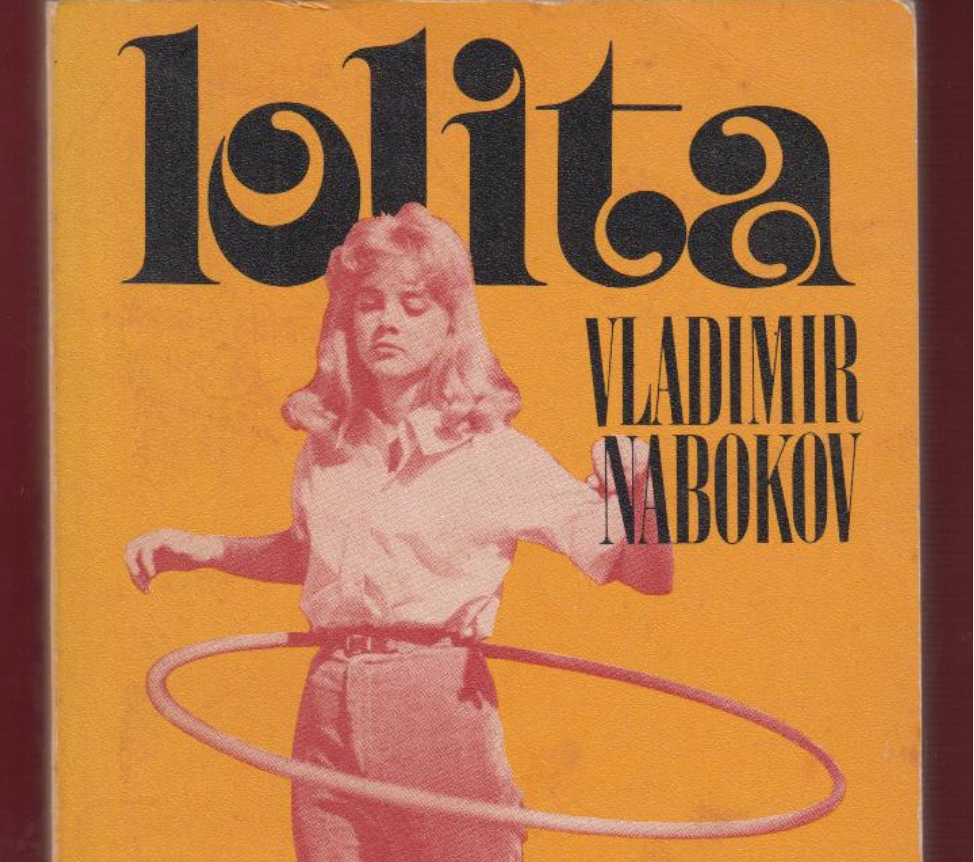

In writing about what Hockenberry’s friend calls an “overcorrection” of a “revolution,” Hockenberry discusses Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. He claims that the 1955 novel “was considered pornography before it was declared a work of art.” Hockenberry feels “absolutely certain that Lolita would never be published today.” Perhaps his essay showing up in Harper’s could be used as evidence against Hockenberry’s claim, but we should at least be able to agree that we spend a lot of time and energy discussing whether a piece like Hockenberry’s “deserves” to be published, and that the standards discussed seem to have little to do with the quality of the story told or arguments made. Whether said standards are based on deeds or ideology or both, I don’t think we’re better off for establishing a kind of writer’s “purity” test (unless, again, it’s based on the quality of the work).

The ending of Hockenberry’s essay was weak, largely because it seemed so like a desperate grab for the approval of those—friends, former coworkers, and others in his industry—who “exiled” him. ‘I am a liberal!’ he seemed to want to say, and he combined this assertion with various appeals to his disability that were scattered throughout the essay. Those are moves, of course, that our culture has taught him to make, and, historically, I suspect they served him well…until they didn’t.

As I read Hockenberry’s essay, I thought about a passage in scripture that informs a lot of my own thinking about sexuality: the image of Jesus kneeling down to draw in the sand after he challenged an adulterer’s accusers to be the first to throw a stone at her if any among happens to be without sin. We do well to remember that before we obliterated the word “sin”—with our tendency, on one end of the political and religious spectrum, to shame people with legalism, and on the other end of the spectrum, to be so certain that everyone is perfect as they are, with no need for correction at all—that one of the word’s original meanings was simply “to miss the mark,” a human inevitability if there ever was one.

As such, one of the reasons I continue to be attracted to the way Jesus handles situations is the way he uses different tools. He is both serpent and dove, and he has a way of changing the question by surprising whomever his audience happens to be. Dr. Dan Allender—counselor, author, and founder of The Seattle School of Psychology and Theology—has written that a child needs a “yes” answer to the core question of “Do you love me?” and a “no” answer to “Can I have my own way?” I think you can find those two answers in the way in the way Jesus responds to both accusers and accused. He offers the antidote to what Hockenberry describes in his essay: “an uneasy and often contradictory fusion of sexual puritanism, social progressiveness, secular tolerance, and extreme zealotry of intolerance.”

The gift of this self-examination is the possibility that we might learn to see the person we so desperately want to dismiss.

Instead of: “Do or don’t do X act,” Jesus seems to demand, as entry into an exchange with him, a willingness to engage with the coldness of our own hearts. The gift of this self-examination is the possibility that we might learn to see the person we so desperately want to dismiss. It’s no accident, then, that the accusers drop the stones and walk away, or that Christ turns to the woman and says he doesn’t condemn her either, while also admonishing her to leave her life of sin (a seemingly impossible task, and yet surely not an incidental instruction).

It’s of course true that adultery and sexual harassment aren’t the same acts, but if we read this story and put the moral emphasis on a specific gender or sin or form of punishment, we aren’t reading very well. We ought to be able to imagine ourselves as both the accuser and the accused. Not a word of the story is cheap, which is why the haunting beauty of the scene remains in the canon and hangs in our consciousness. If we’re attentive enough to it, the story also offers us a set of parameters we might use in some of the current dilemmas in which we find ourselves. The arc starts with an acknowledgement that sin (adultery, in this case) occurred, then shows us how quick we are to punish and blame (probably in part because it helps us ignore our own sin), and then we see (and experience) forgiveness, which does the double work of hinting that something else is possible, that life is still available to us, despite what is behind (and surely also in front of) us.

I doubt #MeToo exiles are the only ones who want a more genuine conversation about sexuality, so by all means let’s have one.

This deep invitation is some of what seems so missing in our contemporary conversations about sexuality. In his essay, Hockenberry writes that “If…something is being hauled out as garbage in the crucial domain of human gender relations, social equity, and norms of love and mating, then something new probably needs to replace it.” We can quibble about whether any affirmative vision for sexuality is really all that new, but we need what Hockenberry’s asking for. We have to be aiming at something rather than just avoiding and demonizing and shouting evidence of our own self-righteousness. Hockenberry adds that “What passes for personal guidance on sexuality today is a lexicon of jargon with the goal of avoiding STDs and perverts…The concern for safety is worthwhile. But as a substitute for the elaborate emotional zone…it is not worthwhile.” And: “The hookup narrative starts with a blowjob, continues with a parade of sex toys and orifices that flash by in a few seconds (nanoseconds if the couple is drunk) and ends…in…lifelong regrets.” Indeed these glimpses of Hockenberry wrestling with how unfulfilled his deepest longings seem to be were what I was most open to, what I most craved, in the essay. I doubt #MeToo exiles are the only ones who want a more genuine conversation about sexuality, so by all means let’s have one.

Hockenberry’s answer, though, is “romance,” and it falls so short of what we need. I think of romance as a state or feeling of bliss in the midst of love. Romance, like the intellectual and cultural movement of Romanticism, is a privileging of the ideal. While these special moments are possible and nice—and they can even build when we do the work of cultivating long-term intimacy—we are foolish to think that the parts of a relationship that make us the most uncomfortable are not playing a critical part—probably the most important role—in our inability to love each other well. How will a couple handle its mutual and individual pain? How will it handle awkwardness? Uncertainty? Fear? Sadness? Grief? Tension and conflict? Mistakes and regret?

Let’s even throw out a few concrete examples: after a night of underwhelming sex, do we show up in our embarrassment; will we be present even then? If one partner wants sex on a particular night and the other one doesn’t, will the one who doesn’t get what he or she wants be mature enough to not silently punish the other for an hour, a night, a year? How will the sex be after we watch our spouse interact with or discipline a child in a way we disagree with? What about on nights when we’re feeling less than deeply attracted to our partner? Will we build relationships with enough trust to allow for speaking up in difficult situations that will upset a partner? Or will we betray ourselves and then spite the other as an act of revenge? As Jesus is quoted in another of the Gospels, “Wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.”

I’m sure there are all kinds of variables worth mentioning in a discussion about what might lead to a fuller sexuality, but put me down for a nod to the character required for showing up to honest confrontation and owning one’s responsibilities, combined with the humility to give, and receive, grace.

3 comments

Brian

“He claims that the 1955 novel “was considered pornography before it was declared a work of art.” ”

That’s because it is. It’s really, really sick and vile.

“Hockenberry feels “absolutely certain that Lolita would never be published today.””

This is the stupidest thing I’ve ever read. Has he been in a coma for the past 50 years? Turned on a TV recently?

“Jesus seems to demand, as entry into an exchange with him, a willingness to engage with the coldness of our own hearts.”

I’m no expert on the subject, but my impression is that Jesus basically responds to all questions with the same answer–you’re focusing on the wrong things. When people ask “I can keep my money, right?” or “I can have sex with anyone I want, right?” or “I can punish people who break the rules, right?”, the answer is always the same–what you are asking about and focusing on is not what’s really important.

Fred

“If one couple wants sex”?

Jeffrey Bilbro

An editorial lapse. Thanks for catching that.

Comments are closed.