The title of my essay suggests my goal, which is simultaneously modest and audacious. It is modest because I want to convince the reader that there is a genuine puzzle here, rather than demonstrate a solution to that puzzle. It is audacious because the received wisdom amongst both conservatives and anarchists is that there are scarcely two philosophies more strongly opposed. If conservatives stand for anything, they stand for respecting the existing social order, including the political order. It is not perfect, not by a long shot, but history has shown it has done a tolerable job at securing life, liberty, and property for the vast majority of those who are fortunate enough to live in the West. Anarchism, almost by definition, stands for the liquidation of the existing order in favor of something radically new. How then can the relative absence of conservative anarchists be something in need of an explanation?

First, we need to define our terms. By “conservatism” I mean the Anglo-American conservative tradition. Much has been written about conservatism since the end of the Second World War, but no writer has arrived at a more succinct and illuminating definition of conservatism than Russell Kirk. His writings on the nature of conservatism and the continuity of the conservative tradition remain the definitive works on the subject. I am drawn in particular to Kirk’s conception of conservatism not as a system, but as an inclination of sentiment and habit of mind:

Perhaps it would be well, most of the time, to use this word ‘conservative’ as an adjective chiefly. For there exists no Model Conservative, and conservatism is the negation of ideology: it is a state of mind, a type of character, a way of looking at the civil social order.

The attitude we call conservatism is sustained by a body of sentiments, rather than by a system of ideological dogmata. It is almost true that a conservative may be defined as a person who thinks himself such. The conservative movement or body of opinion can accommodate a considerable diversity of views on a good many subjects, there being no Test Act or Thirty-Nine Articles of the conservative creed.

Later on in the essay from which these quotes are taken, Kirk lays out ten conservative principles that give content to, but do not exhaustively define, conservatism. But I do not want to go into these principles in detail, as many others have already done. The important point from the above passage is that conservatism, as an adjective, can be viewed as a modifier. In fact, it would not be improper to classify Edmund Burke, the first and greatest conservative in Kirk’s sense, as a conservative liberal. Burke after all was a Whig in Parliament, a defender of the post-1688 political order in Great Britain, who often spoke out in favor of the American colonists during the Revolutionary War and self-consciously drew several principles of his thought from the less rationalist strains of the Enlightenment. If “conservative liberal” is not a contradiction in terms, perhaps “conservative anarchist” need not be, either.

Of course this depends on the definition of anarchism. This term is quite difficult to pin down, because it has been used to describe many different, and often contradictory, proposed social orders, as well as the movements dedicated to achieving them. The definition of anarchy I use here is systematic opposition to the modern state. “State” is also difficult to define, but a modification of Weber’s conception—the state is the organization that possesses a monopoly on the creation and enforcement of social rules—strikes a good balance between breadth and precision. Political thinkers across the millennia discuss the nature and purpose of government. But it is important to note that Roman jurists, medieval Schoolmen, and philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment based their political commentary on observations of quite different institutional landscapes. The institutions these writers lived under varied so greatly that we would lose more than we would gain were we to force them all into a single concept. In fact, the term “the state” as applied to a unitary, corporate organization that governs a territory probably originates with Machiavelli in the 16th century. Accordingly, the state should not be equated with formal governance institutions, nor public authority per se.

So to make a complicated matter as simple as possible, an anarchist is somebody who regards the existing, post-Westphalian form of the state as illegitimate. This does not commit the anarchist to any particular course of political action. An anarchist need not be a revolutionary, for example. Nor does it mean the anarchist is opposed to all forms of rules and hierarchies. Anarchists frequently make a distinction between government and governance. All human societies need the latter, both as a means of checking the passions and inculcating virtuous habits. But the former is simply one way of achieving the latter, and historically considered, a relatively young and untested one at that.

A Skepticism Regarding Centralized Authority

With these definitions of conservatism and anarchism, several points of contact become apparent. I will discuss three that strike me as the most salient and interesting. First, within conservatism there is a robust tradition of hostility to centralized domination and control. We do not need to consult any esoteric sources to see this. The Western canon exhibits it plainly. For example, consider the story of the formation of the kingdom of Israel, recounted in 1 Samuel 8. The Israelites have demanded of the prophet Samuel that he make them a king to govern them. This distresses Samuel, who prays to God for guidance. God regards the people of Israel’s demand for a king as a lack of faith in His providence. He gives Samuel a warning to take back to the people of Israel:

These will be the ways of the king who will reign over you: he will take your sons and appoint them to his chariots and to be his horsemen, and to run before his chariots; and he will appoint for himself commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties, and some to plow his ground and to reap his harvest, and to make his implements of war and the equipment of his chariots. He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers. He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive orchards and give them to his courtiers. He will take one-tenth of your grain and of your vineyards and give it to his officers and his courtiers. He will take your male and female slaves, and the best of your cattle and donkeys, and put them to his work. He will take one-tenth of your flocks, and you shall be his slaves. And in that day you will cry out because of your king, whom you have chosen for yourselves; but the Lord will not answer you in that day.

This warning is pretty clear about the domineering nature of the institution Israel seeks to create. Despite this, Israel remains obstinate. Samuel, with God’s approval, reluctantly grants their request. Much of the Old Testament details Israel’s struggle with this Faustian bargain.

Next, consider St. Augustine’s famous passage from Book IV of City of God. Writing against the prevailing view that Rome’s fall from glory was due to her abandonment of her ancestral gods for Christianity, Augustine is adamant that the glory of Rome—the glory of any earthly political order—is a mirage. They are used by God as instruments of His will, but they are not properly objects of veneration. Many earthly kingdoms, even those God made use of, have been wicked. Rome is no different. Unless they reign with justice, the standards of which no mortal man may change,

…what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? The band itself is made up of men; it is ruled by the authority of a prince, it is knit together by the pact of the confederacy; the booty is divided by the law agreed on. If, by the admittance of abandoned men, this evil increases to such a degree that it holds places, fixes abodes, takes possession of cities, and subdues peoples, it assumes the more plainly the name of a kingdom, because the reality is now manifestly conferred on it, not by the removal of covetousness, but by the addition of impunity. Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, ‘What thou meanest by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, whilst thou who dost it with a great fleet art styled emperor.’

This may be the most flagrant denial of any essential difference between a prince and a plunderer in Western political philosophy. Admittedly, both prince and plunderer have important roles to play in Augustine’s uniquely Christian philosophy of history, and not all rulers are equally bad. Power can be at least partially civilized. But fine leather and polish do not alter the reality of a boot on your neck.

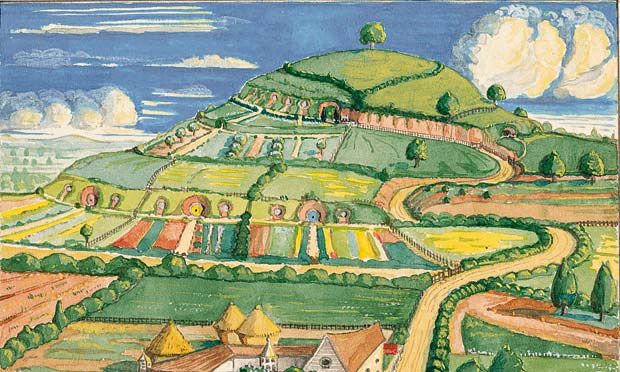

For a modern example, we could hardly do better than J. R. R. Tolkien. Tolkien was a staunch defender of the Western cultural and intellectual patrimony. Many conservatives regard his writings not just as captivating fiction, but as timeless works of literature that reflect deep truths about the human condition. His private correspondence reveals a great deal about how Tolkien viewed coercive power, both in his books and in public affairs. The One Ring, for example, can be viewed as an allegory of power itself, in the sense of the urge to dominate. And in a letter to his son Christopher, his views become even more explicit:

My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning the abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)—or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy. I would arrest anybody who uses the word State (in any sense other than the inanimate realm of England and its inhabitants, a thing that has neither power, rights nor mind); and after a chance of recantation, execute them if they remained obstinate! If we could go back to personal names, it would do a lot of good. Government is an abstract noun meaning the art and process of governing and it should be an offence to write it with a capital G or so to refer to people . . . . The proper study of Man is anything but Man; and the most improper job of any man, even saints (who at any rate were at least unwilling to take it on), is bossing other men. . . . Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity. At least it is done only to a small group of men who know who their master is. The mediaevals were only too right in taking nolo episcopari as the best reason a man could give to others for making him a bishop.

If a staunch “Old Western” man such as Tolkien can sympathize with anarchy, perhaps its congruence with conservatism ought to be taken more seriously. (Tolkien’s linking of anarchy and monarchy is similarly surprising, yet not at all accidental. Rather than digress by discussing “anarcho-monarchism,” I direct the reader to an intriguing essay on the subject by David Bentley Hart.)

A Debt to Christianity

The second point of contact concerns the debt much of conservatism, and a nontrivial part of anarchism, owes to Christianity. It would not be too much of a simplification to say that conservatism is simply the intellectual tradition of Christendom, itself a synthesis of the greatest ideas from Athens, Jerusalem, and Rome. Even conservatives who are not Christians are forced to acknowledge how strongly Christianity influences conservative social philosophy. What is less well known is that there is a well-developed tradition of Christian anarchism as well: opposition to domination and control by the state, grounded in Christian principles. Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, a professor of politics and international relations at Loughborough University in England, has published what is currently the most extensive work on Christian anarchism. Christoyannopoulos’s Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel contains both his analysis of key Biblical passages and explorations of the thought of important contributors to the Christian anarchist tradition, such as Leo Tolstoy, Jacques Ellul, and Dorothy Day. A surprising theme of this volume is that political radicalism can be, and often is, coupled with theological orthodoxy. Due to the outsized influence and reputation of Tolstoy, many who are familiar with Christian anarchism often assume it is associated with heretical beliefs. One of Christoyannopoulos’s valuable contributions is in showing that within Christian anarchism, heterodoxy is the exception rather than the rule.

The anarchism of the thinkers Christoyannopoulos surveys is not incidental; these are not Christians who happen to be anarchists, but Christians who are anarchists because of their understanding of Christian social ethics. Christian anarchists see the state as the primary obstacle to the creation of a just and charitable society. Admittedly, there is a potentially dangerous utopian tendency here. Conservatives are rightly suspicious of any attempts to “immanentize the eschaton,” and a nontrivial part of the Christian anarchist corpus hints at such attempts. Despite this, it is becoming increasingly obvious that their fundamental intuition is sound: the state has revealed itself to be hostile to Christianity as practiced, and may soon become so to Christianity merely professed. A growing number of Christian conservatives are realizing this today. For example, Rod Dreher’s work on the Benedict Option is a strategic call for small-o orthodox Christian renewal in an increasingly hostile social climate. While some of the problems Christianity currently faces are due to generations of poor catechetical instruction, many others are due to the increasing animus expressed towards traditional Christians by the most powerful and prestigious institutions in society, including the state. In order to weather the coming storm, Dreher argues that Christians need to shore up their own institutions and support networks, or else they will find themselves in the position of the foolish man who built his home upon sand instead of rock. To be clear, I am not claiming Dreher is a Christian anarchist, nor that the Benedict Option is a Christian anarchist project. But I do claim there are significant points of overlap between Christian anarchism and calls such as Dreher’s for less political activism and more investments in intentional and semi-intentional communities. These concerns are both deeply conservative and deeply Christian—indeed, conservative because Christian. The concerns of both Christian anarchists and Christian conservatives are of a kind.

A Distrust of Liberalism

The last point of contact between conservatives and anarchists I will discuss is the nature of liberalism. By liberalism, I do not refer to the contemporary American Left. I use it to mean the body of thought that arose out of the Enlightenment—in reality a plurality of intellectual movements, which I uneasily classify as a singular in deference to public usage—that relates to the nature of man, his place in society, and the proper role of his institutions. This is a particularly sensitive point for me. The evolution of classical liberalism, a label I am proud to wear, into progressivism is an uncomfortable fact with which all lovers of ordered liberty must wrestle. Although the ideas that comprise progressivism have transformed almost beyond recognition from their classically liberal forerunners, it is nonetheless true that progressivism is lineally descended from classical liberalism. Either progressivism is inherent in classical liberalism, or classical liberalism morphed into it because of a set of contingent circumstances. In either case, we need to reflect seriously on the durability of post-Enlightenment social structures. This theme is certainly not original to me. It is one of the great questions Patrick Deneen raises and wrestles with in his recent book, Why Liberalism Failed. Deneen locates the malaise in contemporary institutions, including political institutions, in the tendency for liberalism to destroy any restrictions on autonomous individualism. I differ with Deneen on the ultimate explanation: in terms of the earlier dichotomy, I read Deneen as arguing that classical liberalism necessarily became modern liberalism, whereas I deny any such tendency can be found in the specific variant that has its roots in the Scottish Enlightenment. But whatever the reasons, liberalism then has become liberalism now, and we must figure out what to do about it.

Another point of contact between conservatism and anarchism can be seen in the emphasis each places on the state in affecting the transformation of classical liberalism into progressivism. In human societies, philosophies do not interact in the abstract. Philosophies are carried by people, and people interact—and often clash—within institutions. And institutions have a way of selecting for certain outcomes and behaviors, while retarding others. The philosophy of government embedded in progressivism is one of elite technocracy: society’s natural aristocrats ought to harness the means of social control and use them to build, by force if necessary, a better society. Progressivism, as a social system, is thus adaptively well suited to the capture of the state. Since the organizing principle common to its various sub-movements and causes is political power, the existence of an organization with a monopoly on the creation and enforcement of social rules is itself an institutional promoter of progressivism. These philosophies, many of which started out as ideas developed by academics and other intellectuals in the late 19th century, did not only capture the academy. They captured also state governments and, eventually, the federal government. There is thus a self-reinforcing feedback loop between state agents seeking ideological cover and ideological intellectuals seeking state support. For example, it is not a coincidence that as progressives ascended to political power, the art of political economy, which was in Adam Smith’s time a branch of moral philosophy and as often as not practiced by gentlemen-scholars, transformed into the science of economics, practiced by expert academics and re-oriented along the lines of physics and engineering.

Whereas anarchists worry about the growth of centralized power per se caused by the progressive capture of the state, conservatives like Deneen focus relatively more on the effects this has had on local community: the churches, social clubs, and other fraternal organizations that formed the backbone of civil society. These organizations were a crucial buffer between the individual and the state. They also served as sources of meaning, orienting persons within a community towards shared projects and channeling individual talents and desires towards securing the common good. Deneen rightly recognizes that the radical individualism and all-encompassing rights talk of liberalism-cum-progressivism is not only amenable to, but requires a powerful central state. Only such a state could marshal the force necessary to break local communal ties and other intermediate bonds of loyalty. That liberalism needed the state to take its current wrecking-ball form suggests that, for conservatives, something stronger and more definite than skepticism of state power is justifiable.

Both Dreher’s and Deneen’s projects impel vital questions: how can the Faith be preserved, and how can we protect ourselves from the progressive strain of liberalism? Perhaps a synthesis of anarchist and conservative postures can yield answers. Taken collectively, the above points suggest there is substantial common ground between anarchism and conservatism. Given this common ground, the relative absence of those who would identify as both anarchist and conservative is in fact a puzzle. The solution to that puzzle is far beyond the scope of this exploratory essay. And obviously there are still tensions between anarchism and conservatism, as I have defined them. But hopefully those tensions can be fruitful, stimulating intellectual activity to figure out how to save what is best in the legacy of Christendom from the inevitable—and, in some sense, understandable—post-Trump Left’s ascendancy to power. The only alternative seems to be to continue with conservative political activism, whether in its familiar and tired Movement Conservative variety or something at least nominally new. Such approaches have often yielded electoral victories, but almost never lasting protection for the good, true, and beautiful things in life. Conservatives trying to achieve their goals by controlling the state is fighting fire with fire. It is a natural response, and one can be perfectly well intentioned while desiring to use the weapons of the enemy against him. Such was the path of Boromir. But we know how Boromir’s story ends.

23 comments

Thomas Storck

https://distributistreview.com/how-i-didnt-become-a-conservative/

https://ethikapolitika.org/2015/04/08/futurists-and-conservatives

Tim H

As we’ve heard endlessly in the past few years. Politics is downstream of culture. And as Paul Gottfried has recently said, it’s probably more of a circle. But the issue is that the political structures no matter how well circumscribed need culture to keep them in check.

So it seems the healthy advice from this article is that culturally we should be a lot more skeptical of State power.

JCM

Excellent, thought-provoking article, but I’m still finding the definition of “conservative” slippery enough to blunt the force of the argument. If conservatism is primarily defined as anti-liberal (traditionalist?), then the “King and Country” Tories were conservative and post-war American free-market conservatives are not. If conservatism means distrust of central authority, the opposite is true. If by “conservative” we mean traditionalist anti-authoritarians like the early Quakers or the Benedict Option folks, then yes, maybe they and the anarchists should talk. I have to say though, it will make me roll my eyes a little if traditionalists discover anarchy now that their views no longer have the force of law and cultural sanction. Tolstoy saw very clearly how tradition and an abusive State could work hand in hand.

John C Medaille

This is very good, but I think there is a central contradiction that must be faced: Wouldn’t such “anarchism” merely enable economic and military predators? Societies have to be able to both provide for themselves and defend themselves (the world being what it is, what it has always been). IOW, to make anarchism work would require a strong authority. Can you really have anarchy when corporations are more powerful than states? Can it defend itself when states have tanks and bombers?

Economic anarchy (laissez-faire) has always led to its own opposite: an totalizing state controlled by corporate collectives. And political anarchy has led to military chaos, as after the collapse of the Carolingian Empire. These are the practical problems we as front-porchers must deal with.

I think the problem is exemplified by Kirk’s rather odd choice of Burke as the founder of modern

conservatism. True, he did say some nice–if often silly–things about the ancien regime, but he was a liberal through and through.

Brian

“IOW, to make anarchism work would require a strong authority. Can you really have anarchy when corporations are more powerful than states?”

Such a bizarre pair of statements for a distributist to make. Strong corporations exist primarily because of strong states.

“Can it defend itself when states have tanks and bombers?”

I find it inexplicable that people in 2019 still say things like this. It’s been shown quite decisively in recent decades that a people who don’t want’ to be ruled by tanks and bombers won’t be.

Tim H

Brian, exactly right!

Nicholas Skiles

This^. For all my sympathies to a kind of righteous indifference to authority, true blue anarchy is a mess. And very true of Kirk and the American conservative legacy.

Jesse Hake

John and Nicholas, can either or both of you point me to some reading and/or unpack for me a little further how Burke “was a liberal through and through”? It fits some ideas I’ve been trying to follow and that I’d like to better understand.

Nicholas Skiles

John, when are starting a “Monarchists on the Porch” club? I’ll get t-shirts made. I think it may just be me, you and Matt Cooper. The shirt should say, “The Last of the Weird Old Tory Communards” with pictures of Chesterton, Tawny and Ruskin.

Nicholas Skiles

While we are on the subject…

Russell,

did you have the chance to see/ give this a read?

https://www.plough.com/en/topics/justice/comrade-ruskin

Nicholas Skiles

I won’t begrudge you that. But there is definite kinship between the Ruskin’s peculiar “communism”, Tawny’s “guild socialism” and Chesterton/Belloc. I’m big tent in my economic heterodoxy.

Russell Arben Fox

Hey, no way you guys, us socialists get to claim Ruskin.

Nicholas Skiles

I’ll defer to John there as this is above my pay grade. I’m still very much a rookie myself. But suffice it to say that the Enlightenment is the Enlightenment. Where one falls along the spectrum from Burke to Voltaire doesn’t matter, a liberal is a liberal. In so much as liberalism means “progress” and conservatism an opposition to (or realistically, a steady acquiescence to) “progress, those terms are constantly being redefined. But if we are pinning the term liberalism squarely on the Enlightenment and it’s fruits, then we might as well be talking about the air we breath. Even those of us who are ardently critical usually unwittingly share some of those assumptions. After all, we don’t know any other world. Even the resident monarchist sympathizers here (John and I among them) have some kooky, heterodox ideas about economics that probably wouldn’t be conceivable prior to the Enlightenment (no matter how much Chesterton and Belloc might insist that Distributism is just normative and common sense).

Nicholas Skiles

Valid. Though it depends very much on what we’re bracketing. For all that I might find much to object to in Voltaire, I’m not without my quibbles with Burke. I’m not sure about “less to bracket.” Maybe different things to bracket. That depends very much on where you’re coming from. I’m not married to any ideology/ philosophy beyond my religious commitments. I don’t fancy myself a conservative or liberal. I’m broadly interested in unpopular ideas. Though, that comes with more brackets than you can shake a stick at.

Rob G

“Where one falls along the spectrum from Burke to Voltaire doesn’t matter, a liberal is a liberal.”

True as far as it goes, but some liberals are considerably less “liberal” than others, otherwise the spectrum wouldn’t exist. It’s a mistake to categorize as “conservative” only those who reject liberalism root and branch. I don’t think we really want to equate, say, Tocqueville and J.S. Mill, or Kirk and Trilling, or, to be somewhat silly about it, Berry and Kerry.

This is not to say that we should ignore the inconsistency that pops up from time to time in these “conservative liberals.” When noticed it can be bracketed, and then we move on. But I’d argue that there is considerably less to bracket in Kirk than in Trilling, which is not inconsequential.

Dan Grubbs

Conservative anarchists … I may just adopt this as a self descriptor in that I work very hard to conserve creation as it was created and an anarchist in that I want to disrupt and displace the industrial form of agriculture for a more regenerative form. Would that be an appropriate understanding of your meaning, Mr. Salter?

Russell Arben Fox

A thoughtful essay, Alexander; I appreciated reading it this morning. While I am not a scholar of anarchism, I’ve done some reading in that vein, so I offer one thought, for whatever it’s worth.

I think I see a tension in your argument, one that you’re probably aware of as well, as that is, of course, regarding liberalism, which I take very broadly to mean the whole sweeping project of establishing, protecting, and enabling individuals to freely act upon their natural liberties without facing coercion (whether governmental, economic, or social) which they have not democratically consented to. You identify yourself as a classical liberal, which I take to mean that, out of that whole sweeping project, you agree with and value the original 18th-century statement of those liberties: the right to control oneself, one’s actions, and one’s property. You also recognize that what you call progressivism evolved out of exactly that early statement. And you seem, on my reading, to approach anarchism as a corrective to that evolution. Yet the thing called “anarchism,” I think, cannot be contained to opposition to the progressive state. “Anarchy” is the state of the absence of rulers, which would include those that we consent and presumably give over our liberties to for the sake of ordered government. Consequently, if you bring anarchy into the picture, it must mean that your are similarly opening the door to doubting the value of, or even the ontological existence of, those natural rights upon which certain individuals may legitimately premise and exercise rulership in the first place. In other words, I think looking to anarchism means much more than supplementing a failure in contemporary liberalism; it means questioning a couple of key elements of the whole democratic project that classical liberalism was the founding ideology for.

Note that this isn’t a criticism; I’m more sympathetic to Deneen thank you, I think–in fact, if anything I don’t think Deneen goes far enough in unpacking the costs of certain liberal rights-based formulations, particularly regarding property. It’s not an accident that those who take the anarchist sentiment seriously find themselves either advocating a kind of anti-liberal monarchism or at least aristocracy (as was the case for Tolkien or, as I write in the link above, Henry Adams), or advocating for a radical anti-capitalist politics of self-sustaining communes or such (which is where both Dorothy Day and Tolstoy come into play). Bourgeois liberalism–the liberal markets and individual freedoms of Adam Smith and other Scottish Enlightenment folk–was a fine accomplishment, but also a structurally limited one (as perhaps we are seeing today), and its basic premises will not survive any serious consideration of the anarchist alternative, I think. And frankly, I tend to believe that’s an argument in its behalf.

Brian

This is very good, thank you.

This is indeed a subject that will be quite topical in coming years. “Blue states” and localities are quite openly nullifying immigration law. “Red” localities even in states like NY are quietly but consistently ignoring gun restrictions. It’s not clear to me if Dem politicians running for president actually think they can by fiat ban things like guns and fracking, or if they actually think states like TX will obey them if they do.

So some fleshing out of terms, ideas, etc, is necessary, because things appear to be on the verge of flying apart.

Conservatives should advocate ideas like requiring representatives to live in their districts full time, not in DC, etc., i.e., things to actively fight centralization, and do it soon, because all the energy on the liberal side is to try to completely destroy the last vestiges of local political power.

Nicholas Skiles

I’ve yet to see any conservative–at least of the Washington variety–who wasn’t joining right in with destroying local political power. If absolute power corrupts, it doesn’t really matter what party dominates the Federal government. The tools of the vast military and surveillance state are dangerous in anyone’s hands. As for the compatibility between a conservative, classical liberalism and anarchism, I don’t think that cart and horse fit together at all. The piece touches on this somewhat. I’m most sympathetic to Tolkien here. One man (or woman) is about as limited and small of a central government as you can get, provided they aren’t handed a vast military and surveillance state. Give me a king or queen who is far away, minds their own business and occasionally pays a visit to throw corrupt local authorities in the stocks. I recognize of course, that any monarch, no matter how benevolent can become a tyrant. But our present, American State is a most absolute authority indeed. Whatever internal, party squabbles might exist, no monarch in history was ever so absolute. At any rate, I tend to feel that a proper Christian attitude toward power is ambivalence. Working honestly and quietly, minding one’s own affairs. The powers that be, even they are corrupt, are still used toward divine ends, hard as has as it may be to see. Whatever rulers may have been deemed saints, the tradition of venerating saints finds its roots in honoring the deaths of martyrs. May we all resign ourselves to the latter, rather than foolishly thinking that, if we had power, we would certainly be like the former.

Brian

“I’ve yet to see any conservative–at least of the Washington variety–who wasn’t joining right in with destroying local political power”

Duh. Who ever said otherwise? We won’t conserve anything by sending politicians off to Washington. We need to keep a good close eye on them at home, right next to us. And as for DC, nuke the place from orbit, it’s the only way to be sure

Nicholas Skiles

“Who ever said otherwise?” Certainly no one here. The Porch knows better. As for nuking Washington, I’d rather see it overgrown. Nature rising up to consume it. Maybe that’s just my affinity for post-apocalyptic sci-fi talking. Anyone know of any aggressive plant species that we guerrilla garden with around the capitol?

Brian D. Miller

As someone who was active in those circles for some years it often occurred to me that there were deep conservative roots in that movement. There certainly is a fair kinship. Odd today that they have morphed into some sort of shock troops for the liberal left, protectors of the vast enterprise.

Comments are closed.