Clay County, MO. At first blush, independent interdependence may seem an oxymoron.

Yet people exercise a kind of balance between their need for autonomy and their need for what others provide. How each person strikes this balance depends on their own philosophy and mindset and then the context in which they find themselves. A person is independent in that they make their own decisions and live in that manner while also being interdependent on others because they have needs that cannot be met independently.

While that may seem obvious, where that equilibrium exists is different for every person. I suggest this idea can be seen in communities–individually and communally. A community is not totally homogeneous in its constituents. As Gracy Olmstead recently spoke about at the 2019 Front Porch Republic conference, communities contain mavericks who view it a personal strength to stand alone. As celebrated as the image of the maverick is in the United States, the notion of the good neighbor, as Olmstead discussed, is vital to the existence and success of a community. The good neighbor offers hope and connection, love and limits, and a kind of collaboration that ensures freedom.

What causes humans to gather in communities in the first place? Basic need of food and water offer a partial explanation, but perhaps there is something in our nature that leads us to seek community. In his presentation, “The Unmaking and Making of Community, ” Mark T. Mitchell recalls Simone Weil. His allusion to Weil is useful here to better understand community and what may be our tendency to gather together. Weil wrote in her book, The Need for Roots:

To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.

And to enhance this definition, Mitchell added:

A healthy local community comprises particular people inhabiting a particular place and sharing local customs, activities, and stories. In short, they participate in a complex web of relations that are flavored by the particular history, geography, and culture of that place.

This inherent need for roots balances an individual’s desire for autonomy. In fact, even Olmstead’s maverick is defined by contrast with his community and cannot exist without it. Our need for interdependence is a powerful element in what I call the stickiness of a community. If you prefer a more officious word, you can use cohesion. This is the idea that there are factors that either enhance the stickiness or reduce it, where stickiness is the ability of a community to hold together.

Often, stickiness is enhanced in communities that have a clear focal point. This can be an economic base, such as reliable employment. Or as fellow FPR contributor Barbara Castle related to me, a community can be focused around a school district. This focus gives opportunity—beyond just personal need—for the autonomous person to engage with other members of the community. She also points out that things aren’t always placid in these communities. Intra-community squabbles will lead to rifts. But how much stickiness a community has will affect its ability to endure rifts.

Communities can also be focused on a church. If so, we can have a faith-based community with strong stickiness because its members attend to the needs of others. This centrality is key to creating and maintaining a cohesive and healthy community. I have observed faith-based communities grow stronger in their cohesion when there is a stressor, such as an economic hardship or sickness. Likely this is due to the need for increased collaboration. But, even in a faith-based community, when growth exceeds cohesion it may lose its stickiness and have to subdivide in some way.

Regardless of the focus of the community, when it grows it usually requires some sort of organized collaboration and relationship building. Olmstead points to rural water districts for irrigation as one example of this structure, which is a governing approach. But it does not have to be hyper organized; it just needs to direct community activity and give opportunity for the independent person to participate. There does not have to be an election or even votes, just generalized or implied agreement.

Many urban neighborhoods used to work as communities, and some may still. The critical factor here is that there must be some kind of need that motivates individuals to collaborate. The others-centeredness that is required for a successful community, balanced with individual responsibility, must come from universal, mutually understood needs. An autonomous person’s desire for a quality life requires the cooperation of other members of a community. This is at the heart of independent interdependence. But if the people of a group do not have a connectedness, as both Weil and Mitchell describe, there is reduced cohesion in the community. Proximity alone is insufficient to define community.

Interdependence then results from the needs of community members that can be met by other members. These needs can be social, economic, material, psychological, or even spiritual. In rural villages an interdependence might be the need for several families to pool their labor capacity to achieve a desired end, such as harvesting crops or moving irrigation pipe. They then rotate that labor to meet each family’s need.

Many successful communities end up with a form of management, such as a leader or council or elder group. Though this can dispossess some community members of responsibility, it can serve as a guiding force when the community is large and needs are common. Group management can help deal with conflict in a manner so empowered by the community. A good example where this has been successful is the kibbutz.

Admittedly, the kibbutz movement has undergone a transformation and many kibbutzim have modified themselves in some way. Today, many operate successful large businesses such as factories, fisheries, and farms. Regardless of its economic model, helping to guide the kibbutzim are its central leadership body propped by a democratic process. What is it these leadership bodies are guiding? They are guiding the social and economic context of their kibbutz. This is a context in which a member can operate independently as well as in an interdependent manner because the other members of the kibbutz need them.

It’s interesting that most communities throughout history did not start or evolve into communes in the strictest sense where the group possesses everything in an egalitarian structure. Even the kibbutzim have a leadership structure. I’m sure the reasons why are many, but among them is this need to balance interdependent independence.

As settlers moved west across the North American continent in the 18th and 19th centuries, they formed what many refer to as small towns, villages really. Sure, the local mercantile brought in certain needed goods from afar. And the railroads changed things dramatically. But day-to-day existence was exercised at the independent level. Peasant life might be a good way to explain things, though Americans seem to think peasant is a pejorative term.

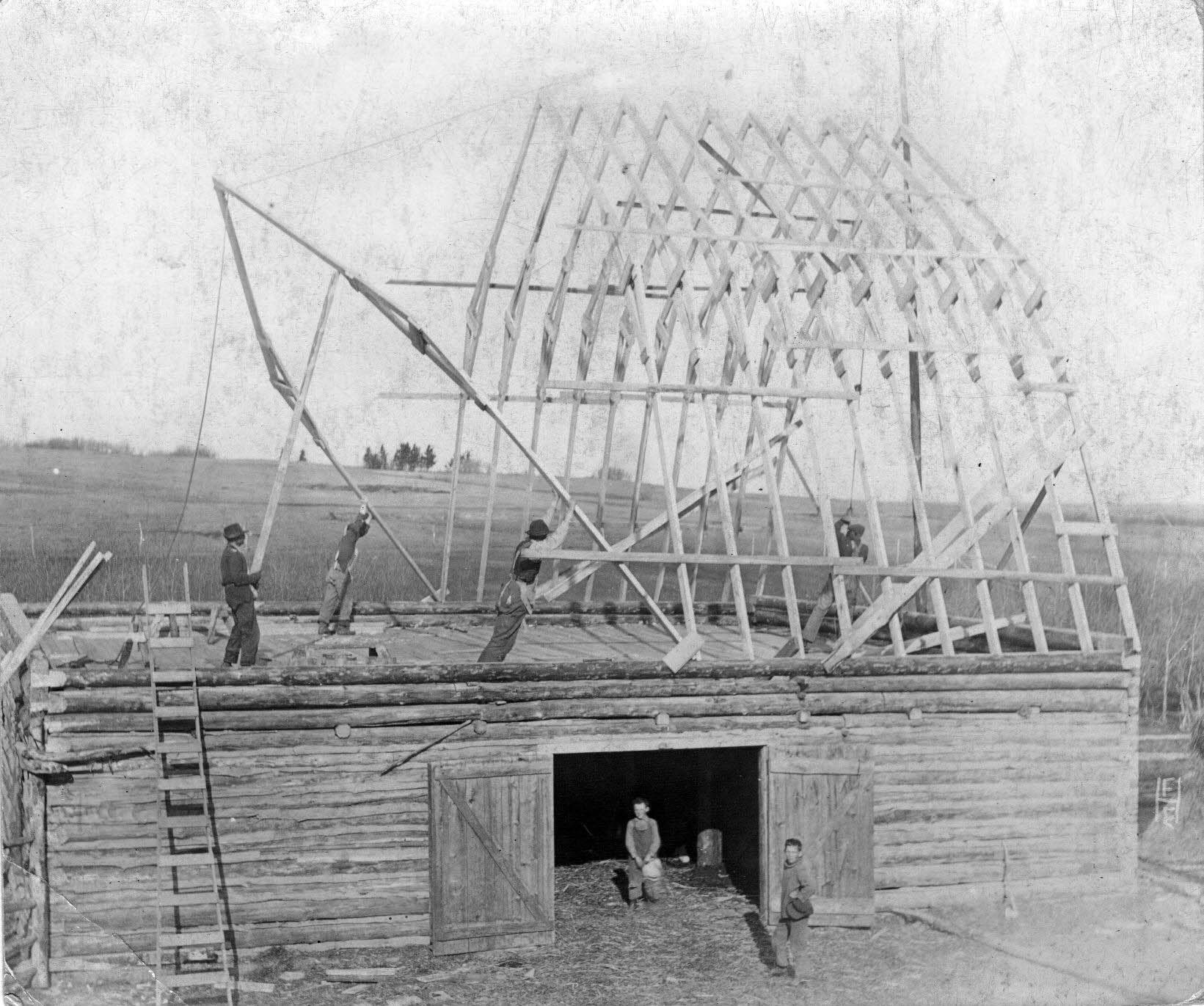

We changed this moniker to “small farmers,” those who often had a little land, produced and preserved most of their own food and lived in collaboration with their neighbors around the village. These communities were filled with people doing what they needed to do to live simply. When some need was larger than what one family could manage, community members would demonstrate useful interdependence and pitch in and help the family. The community forms its own ecosystem. This was done largely with an others-centric attitude, but people also knew they could count on the other families coming to help them when their own need arose. This unspoken guarantee of reciprocity is another factor of cohesion in independent interdependence.

To reinforce the notion of stickiness, I’ll offer Wendell Berry’s description of a community. He wrote in his essay “Conserving Communities,” that people in a community:

take a generous and neighborly view of self-preservation; they do not believe that they can survive and flourish by the rule of dog eat dog; they do not believe that they can succeed by defeating or destroying or selling or using up everything but themselves. They doubt that good solutions can be produced by violence. They want to preserve the precious things of nature and of human culture and pass them on to their children. They want the world’s fields and forests to be productive; they do not want them to be destroyed for the sake of production. They know you cannot be a democrat (small d) or a conservationist and at the same time a proponent of the supranational corporate economy. They believe–they know from their experience–that the neighborhood, the local community, is the proper place and frame of reference for responsible work. They see that no commonwealth or community of interest can be defined by greed.

For rural communities to cohere, they must do so against significant odds. As Berry points out there are great forces against the rural community that see “no value in human community or neighborhood.”

Gatherings of people exist regardless of technology or era. These gatherings experience the dynamics of human relationships. These relationships are often aided by a common sense of place, a common sense of rootedness. Many rural towns and villages in the U.S. have disappeared, mostly due to lack of employment due to the failure of modern agriculture. Yet, there is a small movement of people returning to rural communities. Is it to address their need for rootedness that an urban or suburban setting cannot provide? Are they attempting to reclaim their sense of independence in a context of interdependence?

Time will shortly tell, and though I’m not optimistic, I remain hopeful.

2 comments

Dan Grubbs

Niaz, you just made my day. Thank you very much for your kind compliment.

Niaz

Thanks for this. What a beautiful essay.

Comments are closed.