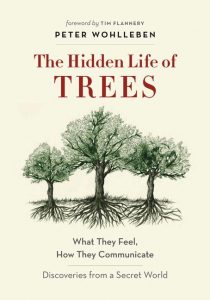

Boise, ID. It turns out that trees are far more beautiful and complex and glorious than I had understood. Do not misunderstand: I have truly loved them. In a childhood far from civilization I played out my imaginings under the canopy of the Idaho Panhandle National Forest. I still pride myself on identifying conifer species from a distance and still long for the cool quiet found under old growth cedars. However, German forester Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees is full of glorious detail about how and why and where trees do all of the wonderful things they do. Yes, do. Still as they seem, they are apparently actively thinking, feeling, planning, nurturing, agreeing, and communing with one another and with fungi, bacteria, and insects.

Wohlleben offers copious descriptions of symbiotic relationships between species, growth patterns, propagation statistics, and risk factors all in heavily humanized terms. Trees can be mothers and the forest a kindergarten. Stages of growth are correlated to childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Communication between trees, whether through scents or slow sound waves, are directly referred to as speech. Wohlleben’s trees scream, sacrifice, and strategize.

Objections to anthropomorphizing the trees can come from two culture-war camps. One is concerned with scientific precision and objectivity. The other is afraid of disordering the hierarchy of creation and privileging trees over persons. One reduces all of life to the simplicity of chemical structure, the other complicates life with spiritual distinctions and rank. Wohlleben travels the long way around from scientific methods to mystical elevation: if human intelligence is described in terms of electrical impulses and animal feeding is analyzed as the breakdown of sugars from plant and animal sources, then the signals trees send through their roots and the photosynthesis their leaves allow are essentially identical to human and animal processes. In the process, he may leave both the humanist (Christian or otherwise) and the nominalist sputtering indignantly. Are trees nearly human or are humans nearly trees?

When Canadian writer Marcello Di Cintio asked Peter Wohlleben if there was danger in anthropomorphizing trees and forests, he replied “Not for the trees.” This seems to be an entirely wrongheaded question and answer, though perhaps the author may assume greater authority for determining right and wrong-headedness in discussions about his book. This question assumes that the significance of a book like The Hidden Life of Trees is its call to action, its activist message or intent. Wohlleben’s effect, seems to me to be nearly the opposite of an activist manifesto. Like my favorite fantasy novelists, though without such intentional escapism, Wohlleben seems to me to be shaping a new lens through which to see the world.[1]

An activist says, “here is an agenda for planning and making the future.” A fantasist says, “here is a compelling vision of the secrets of the universe: be delighted.”

The fantasy of the forests Wohlleben tells is of an ancient community: of mutual regard and wise self-stewardship, of the prudence of age measured in centuries and millennia, of interdependence among various kinds and kindred, of a measured dance between differing rhythms played out on annual, decadal, and centurial cadences.

And, like a great fantasy, The Hidden Life of Trees tells the reader that, surprisingly, this vision is true. The transcendent permanence of Tolkien, LeGuin, and Gene Wolfe is their ability to see the truth of human existence in the created world and imagine it in some new and surprising shape that displays the formerly hidden in a convincing and resonant vision. Trees talk; not as humans talk, but entishly in a slow speech of ultrasonic waves. Perhaps he wants this fantasy to increase environmental activism, but if it does so, I think it will be on a slow timescale and one governed by wonder and love, not indignation and urgency.

I read The Hidden Life of Trees and am not inspired to join the Sierra Club or start a paper recycling program at my workplace. I read and want to go for a walk in the woods. I want to call my naturalist friend and ask him to go for a hike so we can contemplate the trees and have a rambling discussion about the mosses of Idaho, and whether or not the Ent Wives were hidden around the Shire, and if Merry and Pippin would remember, and if that desired reunion was really better than the longing for it. I read and then I do go for a walk along the river and discuss with my woodworker husband and my curious but distracted children the relationship between these cottonwoods and those elms and the difficulties of finding good sturdy trunks for slabbing with the Alaskan sawmill. I read and am intrigued by how much there can be to know and see and feel and contemplate in one forest.

The Hidden Life of Trees is rich with detail about forest health and variety and Wohlleben’s perspective seems to be that their complexity and slow pace are surety against permanent disruption. Bark beetles and fungal infestations are fearful on the span of a human lifetime but are actually mere preparations for a future old-growth forest. And this may be Wohlleben’s best, though possibly unintended, effect. If a human timescale—privileging our experience and our hopes—is insufficient to understand the forest, then maybe we will be provoked to reconsider both the human and forestal timescale. C.S. Lewis once made clear that “nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.”

We haven’t rightly honored the trees. We haven’t given them their due regard as integral beings worthy of contemplation and care. We haven’t loved them enough. And so we must love them more and consider their distant future when our great-great-grandchildren’s grandchildren may walk under their boughs. Love them, not because we consider their future more important or longer than ours, but because their future can take its rightful place of honor in light of the immortality of the human soul. The trees deserve our attention both because they outlive our mortal lives and because our immortal souls will outlive their generations. The long view of the forest may be able to prepare us for the long view of eternity.

All photographs from Cottonwood Creek, northeast of downtown Boise, and taken by Amanda Patchin.

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories”: “I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.”