Grand Rapids, MI. My old tropes are now gone, at least for this year. I used to herald the coming of Spring Training and the beginning of the baseball season with a lament about the weather at home here in Michigan. The easy devices—paradox, contrast, irony—were my rhetorical companions. Longing for the greenswards of Florida would always resonate during the ice storms of early March in these higher latitudes. But now, in 2020, the new season is emerging into a new world—and my lament, as I write this pre-season review, is that it’s 92 degrees here, and even my sunflowers are crying out for mercy.

Thus, in this year of incongruities, baseball’s Opening Day drops right into what should be mid-season. It is and has been a scramble, marked by health considerations and revenue-sharing disputations and the forced hibernation of the minor leagues. I read in the newspaper the other day a page full of new rules for baseball in the COVID-era, and I marveled—no spitting (can that be possible?), no throwing around the horn after strikeouts (will catchers be able to restrain muscle memory?), and pitchers allowed to have damp rags in their back pockets so they won’t breathe on their hands (the discomfort of damp trousers?). But here it comes, strange and stunted and sharply constrained—and so here I go with a review and then a preview.

Before I begin to complain about the shortened season, the lack of travel to the usual hubs, the lack of live fanhood, it might be well to remember those who loved baseball with extraordinary intensity, yet for whom no season of major league baseball ever opened up its bounty. I speak of the great African-American players of baseball’s first hundred years, before Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson broke the color line permanently, allowing baseball to be the harbinger of further cultural changes.

I’ve become interested in the history of the Negro Leagues (my hometown of Grand Rapids had a lower-echelon team for years called the Black Sox), and of African-American baseball prior to the formalization of the Negro Leagues in 1920, stemming back to nineteenth-century figures like Octavius Catto, a leading Philadelphia advocate for African-American teams to be included in all-white leagues, and the brothers Moses Fleetwood and Wilberforce Walker, who played briefly and courageously for Toledo of the American Association during the 1884 season, pre-dating Jackie Robinson by six decades.

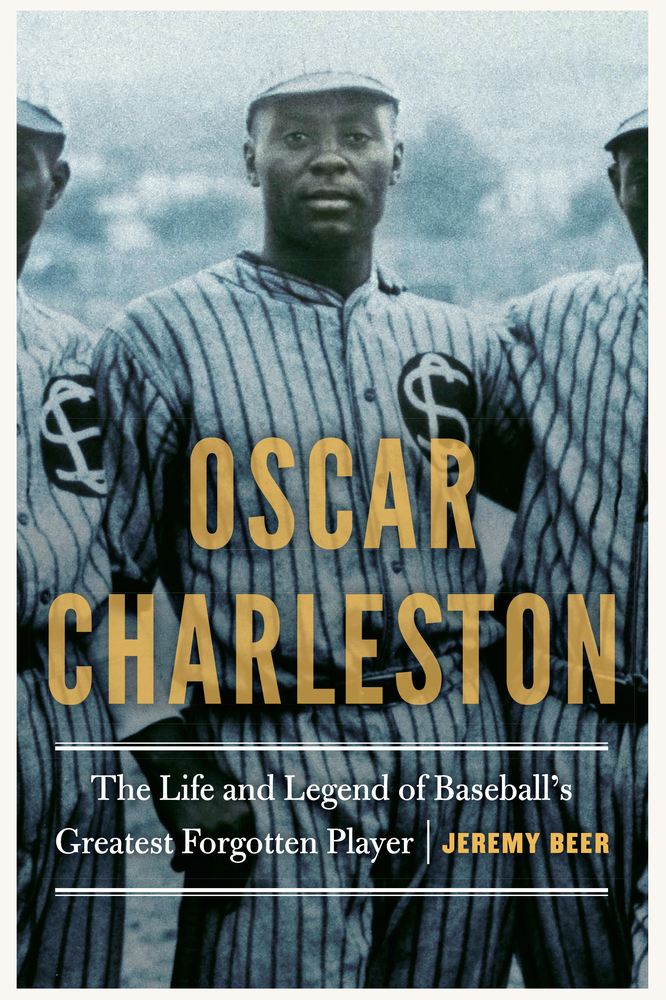

Thus, Jeremy Beer’s Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player filled a tremendous gap for me with style and grace, much like Charleston himself once filled center field on the various teams (and there were many) on which he starred. Beer has discovered a crown jewel of baseball history, and his thoroughness and care show how long and hard he worked to mine the story of a lost hero. Indeed, his “Introduction,” subtitled “Craftsman,” shows that none other than the father of sabermetrics and analytic baseball, Bill James, had unearthed enough of Charleston’s career, statistically, to declare him among the all-time greats: “Only Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Willie Mays were greater than Charleston, wrote James, who slotted Charleston just above Ty Cobb, the player to whom he was often compared by the press during the early part of his career” (11). James was surprised when, after publishing this in 2001, the ranking of Charleston met with little comment.

Beer also quotes the singling out of Charleston’s greatness by Buck O’Neil, who became an octogenarian star on Ken Burns’s Baseball series—I returned to O’Neil’s memoir I Was Right on Time, and found an additional quote that was stunning: “To this day, I always claim that Willie Mays was the greatest major league player I have ever seen….but then I pause and say that Oscar Charleston was even better” (O’Neil, 25). Perhaps even more telling, as a seed for Jeremy Beer’s research journey, was O’Neil’s double honorific on the man nicknamed Charlie: “the greatest player I have ever seen in eight-and-a-third decades, and one of the greatest men” (O’Neil, 25).

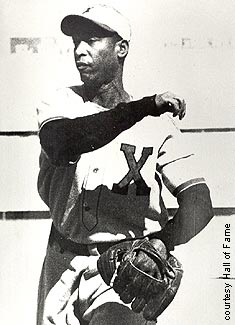

One of Beer’s most extraordinary accomplishments is giving a chronological narrative through the labyrinthine career of Charleston, from military ball in the Philippines, through a score of Negro League teams, winter ball dates in Palm Beach and in Cuba, and various barnstorming ventures, and then on into the managerial ranks and the grooming of younger stars—including Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson—up through to his final gig, managing an Indianapolis Clowns team that had just lost their young shortstop, Henry Aaron, to the big leagues. Beer manages to keep the narrative cogent, with Charleston’s achievements, captured through newspaper accounts and eyewitnesses, stirring the imagination at every turn.

Furthermore, Beer is able to bring some of the human interest, the qualities of personality and character of Charleston, out of the dearth and scattering of evidence. This is good history, good biography, and ultimately good ethics, to show the human face, the dauntlessness and charisma of this man who had all but disappeared, but whose mien is a rebuke to the shallow celebrity culture, in sports and elsewhere, that now clamors for constant attention. There is something of the Aristotelian Magnanimous Man emerging from Beer’s account of Charleston—a man of thumos, to be sure, who learns to control it, while showing the highest level of perfection within his craft, his techne, all the time making those around him better, and garnering a respect that fractured that most heinous of boundaries in twentieth-century America, the ‘color line’ of bigotry and injustice. Beer has shown us a great player, through the tools of anecdote and statistic and baseball’s quirky measuring sticks—but in the deep core of this narrative, Beer has shown us something even better, the development of a great-souled man (that is, unless a particularly inept umpire, or a cocky third-baseman blocking the bag, or a bullying heckler in the crowd, got in his way!).

The early years of Oscar, growing up in Indianapolis, are paradigmatic of the hard-scrabble life of many African-American families who’d left the south for northern cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Constant changes of address for the family, sporadic employment for the parents, and dangers on the streets for the kids—including trips to the Indiana Reform School for Boys by two of Oscar’s older brothers—betoken a chaotic existence, with work as a batboy for the local African-American team, the ABC’s, as a place of solace. But Oscar’s decision to join the army as a 15 year old (he changed his birth year from 1896 to 1893), indicates a desire to escape and find some stability. Beer closely follows the emergence of Oscar as a baseball player in, of all places, Manila, where he appears for his regimental teams as a teenaged left-handed pitching ace, during the 1913-14 Manila League season, at exactly the same time another teenaged lefty, a year older than Oscar and raised in circumstances not dissimilar, was being courted and signed by the Red Sox—George Herman Ruth, who would soon gain the moniker “Babe.” The careers of the two would continue on parallel but very different paths for the next 20 seasons—segregated in every way, except by the measure of their mutual greatness.

Unlike the Babe, Oscar seems to have striven to improve himself through his company and habits (he eschewed tobacco and alcohol throughout his life), so that his superior officers in the Philippines and the American governmental delegation wrote him a letter lauding his play and the quality of his companionship (he was still only 17 years old!). Even after he snapped at the end of his rookie year with the Indianapolis ABC’s back home in 1915, punching out a white umpire in an interracial post-season all-star showdown (his sharp temper, a family trait, would flair up occasionally throughout his career)—a lapse for which he received the censure of the ABC’s urbane owner-manager C.I. Taylor and the African-American press—nonetheless Oscar’s letter to the Indianapolis Freeman on November 1, 1915 shows a degree of self-knowledge and self-articulation surprising for a young man who’d just turned 19: “‘Realizing my unclean act of October 24, 1915, I wish to express my opinion. The fact is that I could not overcome my temper as oftentimes ball players can not. Therefore I must say that I can not find words in my vocabulary that will express my regret pertaining to the incident committed by me, Oscar Charleston, on October 24th’” (71). This doesn’t seem the usual braggadocio brawler of early twentieth-century baseball, but a young man learning and growing.

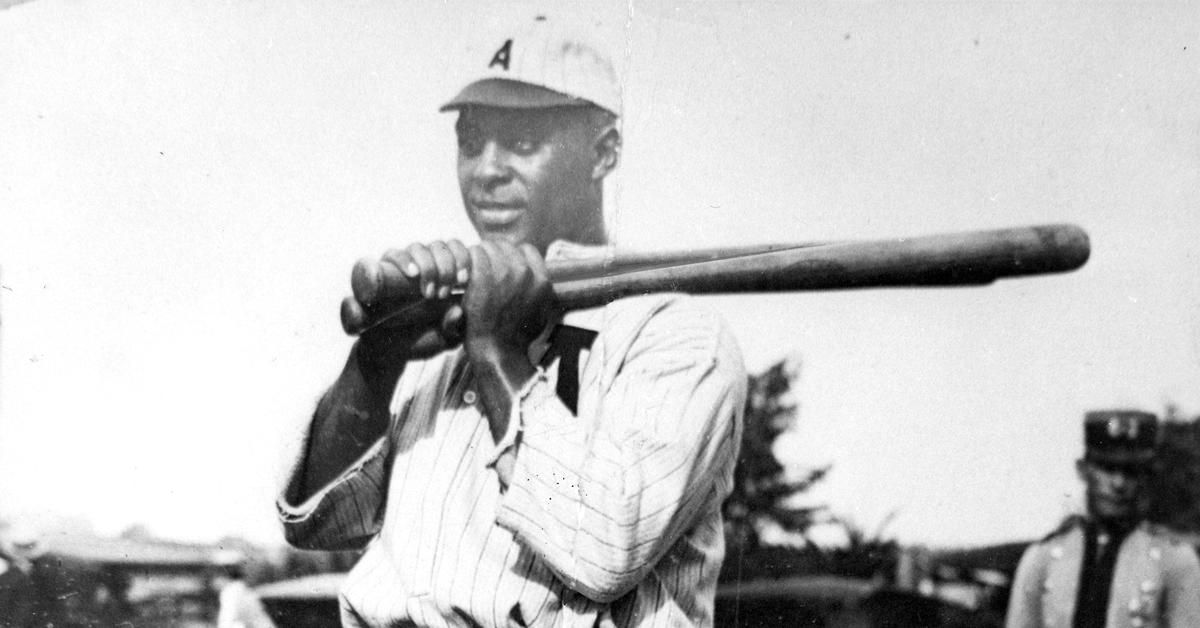

Beer’s treatment of Charleston’s rise to the status of greatest player in black baseball is well-paced, as Oscar seems to add aspects to his game, from the aggressive and even violent baserunning that earned him the sobriquet “the black Ty Cobb,” to the extraordinary range and style in center field that earned him the further title of “the black Tris Speaker” around 1920, to the surge of home run hitting and offensive productivity which, in 1921, gained him his most enduring comparative nickname, “the black Babe Ruth.” The Babe in 1921 was unreal, hitting .378, with 59 HR, 168 RBI, 171 Runs, 44 Doubles, 16 Triples, and an unearthly On Base plus Slugging Pct. of 1.359! The Babe played in 152 games that season—Oscar played in roughly half that, 77 league games. Oscar’s batting avg. was .433, and if his other stats were doubled, he would have 30 HR, 191 RBI, 218 Runs, 36 Doubles, 25 Triples, and 67 steals. Plus, he was an elite defensive center fielder, whereas the Babe was a somewhat indifferent corner outfielder. All weighed in the balance, the two best individual seasons ever in baseball may have been by Oscar and the Babe, both in 1921. And, as if to prove that no disparity between the Negro Leagues and the white Major Leagues would sully his achievement, Oscar led an all-star team of Negro Leaguers out in the California Winter League, where they tangled with the Yankees’ Bob Meusel (the Babe’s long time roommate), his brother Irish Meusel of the World Champion Giants, and a bunch of other Californian Major-Leaguers in 11 games in January and February of 1922. The Negro Leaguers won 7 and lost 4, and Oscar was lauded by the press as “’the hero of the series’” (129), hitting .405 in 79 at bats, and gaining the upper echelon of compliments when a white reporter called him “’without a doubt the second greatest living baseball performer in the entire universe, the great Babe Ruth being his only peer’” (130).

Charleston’s achievements in the mid to late 1920s, and on through the ‘30s, ‘40s, and into the ‘50s, perhaps qualify him for a half-step above the Babe, because Charleston became what the Babe aspired toward, but never achieved—the status of a successful professional manager. At the helm of the Harrisburg Giants of the Eastern Colored League in 1924, still in his age 27 season (when offensive players usually reach their peak), Oscar managed the whole season, while hitting .405 and slugging .780 with 42 extra-base hits in 54 games. In center fielder, he continued to work magic. An opposing manager and former teammate said of him in 1924: “’He can cover more ground than any other man I have ever seen. His judging of fly balls borders on uncanny’” (162). Beer sums up the achievement with a thoughtful reckoning: “Charleston’s 1924 was so good that, even if we mark it down somewhat for the level of competition in the ECL, it is arguably one of the best all-around offensive performances ever witnessed. Furthermore, Oscar compiled his numbers while playing superb center field defense and acting as his team’s manager. Has anyone ever had a better year?” (165).

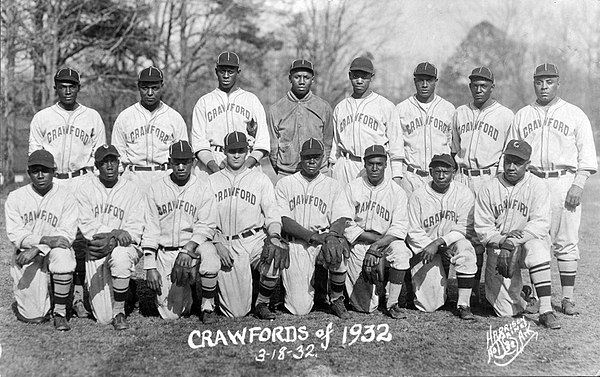

Though the accounts of his tremendous playing prime are stirring—kudos to Beer for including so many newspaper accounts, with their scintillating prose, to stir the imagination on deeds we will never be able to see on newsreels or even in still photos—the period of Oscar’s late career, when he both managed and manned first base for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a team that owner Gus Greenlee assembled like a permanent all-star team, adding the teenaged power-hitting phenom Josh Gibson and an up-and-coming pitcher in Satchel Paige to a team of already established players, with Oscar still the brightest star and draw for crowds. Though he was still a feared hitter and now a stylish first-baseman (apparently the one-handed catch, which he pioneered in centerfield, he also pioneered at first base, to the awe of the fans). But Beer brings out another aspect of Oscar’s impact, one that likely contributed to his fading out as the prime mover of the Negro Leagues: “Nevertheless, it was the emergence of Paige and Gibson under Charleston’s watch that constituted the story of the season. Oscar has rarely gotten any credit for their development; he is at best a bit player in the standard biographies of both men. Yet perhaps, given the esteem in which he was widely held for his managerial skills and temperament, he ought to get a little acclaim for shepherding the two young men toward stardom” (233). For a proud and accomplished man like Oscar, dealing with Paige’s undisciplined and free-wheeling ways without utterly dismissing him, and fostering Gibson’s emergence as the game’s preeminent hitter without resenting him, shows a depth of character and a sense of generosity.

He also showed off his unquestioned leadership skills when he led his Crawfords squad through the intricacies of the social order of Jim Crow America in the mid-1930s, standing up to a white mob in the parking lot of an Arkansas ballpark—“when an angry mob engaged the team as it left, Oscar ‘went nose-to-nose with the ringleader and backed him down.’ Gibson and [Ted] Page stood right behind him. Oscar had forged a true team” (247). And even after a brawl ensued between the Crawfords and the Dizzy Dean All-Stars, Dizzy was generous in his praise of the talent of Negro League stars: “After agreeing that Josh Gibson would be worth $200,000 in the Majors, he added, ‘Another guy I think could have made the grade in the majors was Oscar Charleston. He used to play against us in exhibition games. He could hit the ball a mile. He didn’t have a weakness, and when he came up we just hoped he wouldn’t get a hold of one’” (246). Over and over again, through anecdote and accolade, Beer works on the trajectory of his thesis, helping us un-forget this greatest of baseball talents, to see him through all those other sets of eyes who admitted they’d never seen his equal.

Even though Satchel Paige defected from the Crawfords in both 1935 and 1937 (the first time was to play for an integrated team in Bismarck, North Dakota, chronicled in the fascinating book Color Blind: The Forgotten Team That Broke Baseball’s Color Line; the second time he was recruited by agents from the Dominican government, as portrayed in an equally fascinating book The Pitcher and the Dictator), Charleston finally found his championship success as a manager, and still had a few swansongs left as a player, as when he hit a dramatic home run in the 1935 Negro World Series off of Martin Dihigo, the greatest of the Cuban players of the era and another ‘forgotten’ great of baseball history.

But the coming of the Second World War and the inevitability of the passage of time saw Oscar’s reputation fading among younger African-American players: “If Cool Papa Bell can be believed, what hurt him most was when he noticed the younger black players had no idea how good he had been” (319). (note: apparently the Tigers first-round draft-pick this year, Arizona State slugger Spencer Torkelson, didn’t know who Alan Trammell was until his dad filled him in. Tempus fugit.) Yet, at the very same time, Branch Rickey came calling, making Oscar one of his chief talent scouts as he pondered his grand experiment to integrate the Major Leagues. Beer notes that in his personal scrapbook, Oscar showed a quiet but intense awareness of racial tensions, as “he pasted newspaper articles and illustrations discussing, for example, lynchings, the Constitution’s three-fifths clause, the gubernatorial veto of a compulsory education bill in South Carolina (a bill that would have meant educating black children), and a Depression-era hunger march on Washington”—and though he’d never get to break that color line himself, “Branch Rickey gave Oscar a chance to do even more: to help black players break into the Majors—and thereby fatally prick the bad conscience of white America” (292).

Even toward the end of his life, with many adventures and plaudits in the rear-view mirror, Oscar embraced the role of mentoring young African-American players in the waning Negro Leagues, hoping some of them would get a chance at the Majors, and never expressing resentment, even in his final job, managing the Indianapolis Clowns that had just sent Henry Aaron up the ladder and now were part vaudeville (with King Tut the baseball clown as perhaps the chief attraction, and their two female players also audience favorites). As Beer points out, men of lesser character would have grown bitter in such a role, but Oscar saw it as a way to keep alive at least a few young men’s dreams. When he died in Philadelphia, alone and estranged from his wife, the flood of recognition had reached stratospheric heights, so that even the aged Honus Wagner, a sure top-five all-time player, had chimed in: “’I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around,’ said Wagner, ‘and have yet to see one any greater than Charleston’” (328).

So, how did he fade from view so absolutely, even after the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues elected him to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976? History can be cruel and unjust, just as society can be at any given moment in that history. But Jeremy Beer has sought to bring a measure of justice and kindness to history, with his phenomenal reconstruction of a life well-worth knowing, celebrating, and teaching to the next generation. This man who backed down from no one, who once tangled with a Cuban third baseman and his brother, a Cuban soldier who leapt from the crowd, who played with such grace and zeal that a white journalist who saw the young Willie Mays could find no better descriptor than “Charlestonian,” who relished the post-season match-ups with white major leaguers and more often than not left them in shock and awe at his abilities—this Oscar Charleston, if he has been “baseball’s greatest forgotten player,” has a chance to bear that title no more, now that Jeremy Beer has re-introduced him to the world of baseball and beyond. We can all be thankful for the gift this book has given us.

As for this 2020 truncated season, this mad dash of 60 games instead of the marathonic 162-game grind, this season of inflated rosters and mandatory health tests and rancorous salary disputation—well, who’s going to win this strangest of World Series crowns? Several of the lineups around the league are loaded, notably the young and hungry Dodgers (how did they add Mookie Betts to that already potent lineup?), the North Country Bombers aka the Twins, the deep and dangerous Yankees, even the inglorious Astros and the seemingly underachieving Cubs. But how many players from each and every squad will have to be quarantined, how many injuries will ensue from the upset rhythm of physical training? So many uncertainties endure that I’ve decided to just roll with the closest historical precedent to this season, the weirdly split 1981 strike season. That system of first-half and second-half division winners was sharply flawed—the Reds and Cardinals had the best overall records in the NL for the full season, but neither won the half-seasons, so neither made the playoffs! But the second half of that season, starting July 31st after a 50-day strike break, and comprising somewhere between 48 to 54 games, depending on the team (did I mention imbalance and inequity in the standings that year?!), gives something of a parallel case.

Hence, I will make direct corollaries from 1981 to 2020, eschewing any tangible evidence of change in composition and quality of the teams between now and then (and leaving Colorado, Arizona, Tampa, and Miami totally out of the equation, which seems to work, actually). So, who do we need to look out for in the American League? Well, here’s the first problem—the Brewers had the best record in the AL in the second half of ’81, but they’re in the NL now! Okay, they’ll be an NL contender this year. In the AL, the Red Sox will contend (not very surprising), but so will the Tigers (hometown bias for me—no! I’m just dispensing historical information) and the Orioles (okay, both are surprising). Since we had no Central Divisions back then, I’ll just go with the best records across the board—so yes, the Royals will also shock the world (why are people foolishly picking Detroit and KC in the basement for this year?!). I guess the extra wildcard will be the A’s, then, and so a whole set of surprises awaits in the race to the AL pennant this year!

But wait, a glance at the 1981 second-half NL standings reveals the Astros at the top of the heap—but of course, they’re in the AL now—so that spells good-bye to Oakland, as the bad boys from Houston will be there again, wearing their tacit scarlet letters.

As for the rest of the NL, since the Brewers have already provided a cross-over selection, the next spot will go to the Montreal Expos, now playing under the guise of the world champion Washington Nationals—that’s a serendipitous choice. And this time the Reds will get a chance, unlike 1981, and so will the Cardinals and the Giants, two old NL stalwarts who shared identical 29-23 records back in the dog days of the 1981 season.

So, who will win it all? I suppose the weirdness of 2020 invites a weird World Series, at least from the vantage of history—so let’s say that the NL-AL reversals, these twists of historical fabric, will decide everything—hence it will be the Astros, seeking the redemption of a legitimate, espionage-free title, playing the Brewers for the crown. That actually could work—they are both strong teams, with something to prove (in the case of the Brewers, to show they can win it all, as Milwaukeeans are likely still reeling from Joaquin Andujar’s dominance in Game 7 of the 1982 World Series).

So I’m picking the Brewers to win it all—to win the sprint, despite the looming questions and constraints of sports in the COVID-19 world, despite the small-market and the unwise abandonment of the powder-puff blue uniforms of Harvey Kuenn’s early ‘80s Wall-Bangers. The time has come for the fair city of Milwaukee (directly west of my current home of Grand Rapids, MI, across the fair waters of Lake Michigan) to be the first city of baseball. In a strange year and a strange season, that doesn’t seem so strange.

1 comment

Brian

Professional baseball as we know it is in its death throes.

This abomination of a season will be followed by a strike in a year, and then it will be dead. It’s apparent that the union and the owners hate it each other far, far more than they love the game of baseball. The commissioner, constantly tinkering with idiotic rules, doesn’t appear to even like the game. “People will come” may be the most counterproductive catchphrase ever, as the powers that be think that no matter what they do, people will just keep coming, and spending, forever.

I’d love to see a club system rise up to try to replace it. MLB has decided to kill minor league baseball as we know it, but rather than just whine about it, it could be a great opportunity for a new paradigm, not based on franchises, but more like the club system seen in European soccer, etc. But that’s not the way that 21st century America thinks about anything. Bigger is always better, until it all falls apart.

Comments are closed.