West Palm Beach, FL. While autumn often turns thoughts to transitions, the beginning of this school year, more than most, provokes thoughts of mortality. As K-12 schools, colleges, and universities ponder reopening, they must consider the possibility of COVID-19 deaths. In some states, older teachers are choosing to retire rather than return. Some universities have decided that the best trigger for closing campus will be the first student death. Public attempts to reassure parents by the Secretary of Education have not created a consensus about the school year. As we see the various plans for return, Americans are responding with reasonable trepidation. Education is suddenly considered a matter of life and death. In truth, while the risk of death seems higher this year, there are always lives at stake in education.

We know that education is linked to many outcomes that are often considered measures of success. A college education is tied to higher pay and less unemployment. College-educated couples are more likely to have lasting marriages. College graduates are more likely to own homes. People with college degrees are less likely to go to prison and prisoners who earn a degree are less likely to reoffend. Not only do college degrees seem to offer the kind of stability much of the public wants, they are often part of the path to power and success. We have not had a U.S. president without a college degree since Harry Truman, and every member of the Supreme Court graduated from a university.

More is at stake in education than middle class security or potential access to political power. Whether K-12 or college, education plays a significant role in students discovering and developing their own aptitudes and ability. Education is how people learn about the world around them, past and present, scientifically and socially. Education is where we come to grips with our society and our place in it. James Baldwin said that: “The purpose of education, finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white, to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. To ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions, is the way he achieves his own identity.”

Americans understand that one of the best ways to uplift a community is through education. The Black Panthers expanded youth horizons through its innovative free breakfast program, which sent kids to school ready to learn. Dolly Parton has become a folk hero not just for her music, but for her “Imagination Library,” which gifts free books to children “from birth to age five in participating communities within the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Republic of Ireland.” The inspiration for the project came from the limitations faced by her own intelligent but illiterate father. In higher ed, HBCUs have not only created opportunities for education which were not always otherwise available for African Americans, they have been centers of excellence.

We know that inadequate or inappropriate education is a grave injustice. Those who enslaved Frederick Douglass conspired to keep him from reading. But education transcends institutions, which can be a help or a hindrance, and Douglass learned to read despite efforts to debar him from literacy. When Native American children were taken from their families and sent to schools that wanted to “save the man, but kill the Indian,” their knowledge of self and the world was not expanded but contracted. What Brown v. Board of Education acknowledged to society was that denial of equal education was an exercise in oppression. “The Cheerleaders” who protested the integration of New Orleans’ schools in 1960 knew that school hallways were linked to the halls of justice.

From the beginning, expanding access to education has been part of the American narrative. We associate the “Founding Fathers” with the Constitution and government, but Ben Franklin founded the library in Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania. Thomas Jefferson helped create the Library of Congress and the University of Virginia. In the 1860s, the United States began the Land Grant colleges and, a century later, returning veterans went to college under the GI Bill. The ideal of an educated citizenry and the right to education are so central to U.S. history that the National Guard was called to the University of Alabama in 1963 and Ruby Bridges was escorted to elementary school by U.S. Marshals. Schools cannot solve all of our problems, but access to learning is essential to the structure of our society.

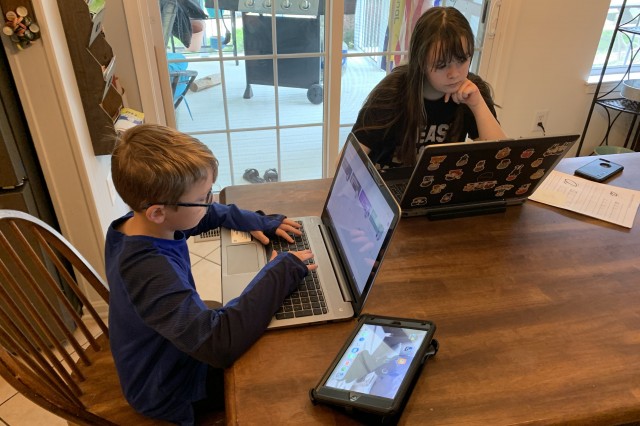

Education, one of our best methods for achieving a more equal society, is imperiled in the 2020-2021 school year. School funding is already unevenly distributed, and schools are more segregated than they were a generation ago, but COVID-19 has added new stressors to the system. We already know that remote learning is leaving some students behind. There are students with limited or no internet access, no home computers, or homes which are not good learning environments. For students who already face obstacles, remote learning widens the education gap. We know that wealthier families will be more able to establish their own educational “pods” for K-12 students with privately hired teachers or to cover the gaps in school offerings with private tutoring, intensifying the inequalities we already see in the college preparatory process. While some families will rebound (or continue) with homeschooling, others will find that option less practical due to new economic pressures.

College students face many of the same challenges. Full-time remote learning is not ideal for many traditional undergraduates and not all have hospitable learning environments at home. Many will miss the support network that exists in on-campus resources and offices. There will be no intense discussions over a meal or late-night study sessions in the library. Some college students may choose to take the year off. However, unlike in other years, those students will have more limited access to a traditional “gap year,” a quality internship, or an entry-level position. Students who delay enrollment or take a year off are also less likely to graduate, thus less likely to secure those positive outcomes that are associated with a college degree. The COVID crisis comes just as there is declining belief in the value of a college degree.

Whether college students hope to return or not, 2020 has exposed the fragility of the existing university system. Very few schools have the financial margin to comfortably weather this economic storm. The decades-long decline in public funding for state colleges and universities has increased the price of college and shifted more of the burden onto the individual student and away from the community, a shift Marilynne Robinson sees as part of a transition of Americans from citizens to taxpayers. It means that more universities are tuition-driven and now find themselves cutting departments and budgets in the face of remote learning and unfilled dorm rooms. Even some schools with large endowments are victims of their own corporate mimicry and administrative bloat. Students may return to universities that post a philosophy statement but have no philosophy department.

As we look at our country, divided over history and by economics, home to scientific innovation and scientific ignorance, education is both more needed and more endangered than ever. In 1961, Jane Jacobs published her classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. It was a book that went on to shape how generations would think about urban planning. This fall we are facing the questions of life, death, and American education. It is a season which has the potential to shape how generations understand education.

As educators and educational institutions ponder their plans, it should be remembered that there are more than deaths at stake, there are also lives at stake. The later lives of students are shaped by their educational experiences. Whether on camera or in person, students deserve the liberating perspective that access to ideas and intellectual engagement can bring. There will be individual and local decisions about the format and content of this academic year, but this is not a year to deemphasize education or settle for substandard pedagogy. The challenge of 2020 brings an opportunity for a collective decision by our society, to find ways to re-invest in education as a public good. This is a year to adapt and innovate to bring ourselves closer to a fuller realization of our culture’s foundational principles.

2 comments

Martin

As usual, Prof. Stice makes some excellent points, such as reminding us of “public good” and emphasizing lives over deaths.

Decline in public funding clearly has an impact on the cost of college, but so do the increasing cost of facilities (hitech labs, airconditioning in dorms, etc.) and the administrative bloat that she mentions in passing — it’s been years since the number of teachers on a typical campus outnumber the other “essential staff”.

In terms of the current crisis, I feel that Brian makes a good point: to what extent does mainstream K-12 education actually “play a significant role in students discovering and developing their own aptitudes and ability”?

It’s ironic that academics apparently shied away from debating the decision to close schools, which seems to be based on panic not rationality. Now that the wheels have stopped, there’s huge inertia to get them moving again.

I saw CNN interview a teacher in FL who said she was afraid to go back to school; I didn’t see them interview anyone like Prof. Stice who rightly points out the inequality and narrowmindedness of assuming that everyone can just study at home.

The COVID crisis has accelerated the trend toward eliminating human teachers, while other aspects of the K-12 system began undermining the humanness of teachers decades ago.

Brian

Yesterday’s article talked about the concept of Rectification of Names, and that’s what I kept thinking about as I read this. Education does not equal school, and school does not equal education. The current “education” system where kids are sent to government run day cares for 13 years then they move far away, in most cases never to return, is completely “unsustainable” and no one should mourn it.

PS. “Some universities have decided that the best trigger for closing campus will be the first student death.”

If that’s the case, then approximately zero universities will close.

Comments are closed.