Dubuque, IA. I’d like to welcome a special guest to the front porch: the writer Ursula Le Guin. I hope she “takes off her coat and stays a while,” as my grandpa always put it, and I think people here will like her, if they don’t already know her. Those who do know her work might be a bit surprised if I suggest that Le Guin has a real porcher sensibility. She’s a left-leaning feminist, an explorer of new territory in sexuality and gender, and something of an anarchist. Needless to say, she often gets invited to other kinds of parties. But this is a time to forge new political friendships. And I suspect people at those parties are missing a lot of what she’s really doing, anyway.

Le Guin, who died in 2018, wrote beautiful fantasy and science fiction stories that escape the usual preconceptions about those genres, without leaving genre behind for the easier respectability of difficult fiction. Her work is very serious and very fun. I came to her through the Earthsea series, stayed on for the short stories and novelas that loosely comprise the “Hainish Cycle,” and return frequently for the many stand-alone pieces, such as the well-known philosophy class favorite “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” the politically astute “The Diary of the Rose,” and the supremely weird “Buffalo Gals Won’t You Come Out Tonight.” In her seemingly bottomless oeuvre there are the usual dragons and wizards and space travel, always placed firmly in the service of narrative and character. But there is also a set of abiding concerns that read like Wendell Berry’s daily to-do list. I would mark three of these:

1. Dispel the myths of progress, without losing hope.

2. Cherish tradition; never romanticize it; always lament its failings.

3. Try to call things by their right names.

Let me take you through some examples of how each of these themes shows up in her work.

Dispel The Myths of Progress

In many of Le Guin’s imagined worlds, the familiar injustices of our own world are conspicuously absent. In some stories, resources are more equally shared, such that no one lives in poverty while others feast, and this fact is barely remarked: thus it has always been. In other stories there is an obvious (but always artful) reversal of the real world, such as a planet in which people with white skin are enslaved by people with black skin. Sometimes she includes a Star Trek-esque element, as when a woman from a culture in which the sexes are equal visits a culture in which women serve men, and must grapple with a kind of prime directive toward cultural sensitivity.

Given these themes, it is not surprising that people take Le Guin for a familiar type of progressive. But she flatly rejects that label. She herself puts it best, responding to a reader’s question about her novel Lavinia (which retells Virgil’s Aeneid from the perspective of the king’s daughter). The reader asks: “Lavinia shows a great love for Rome, or at least pre-Roman virtues. This seems contrarian for a staunch progressive. Or is it?” Le Guin replies: “I am not a progressive. I think the idea of progress is an invidious and generally harmful mistake. I am interested in change, which is an entirely different matter. I like stiff, stuffy, earnest, serious, conscientious, responsible people, like Mr. Darcy and the Romans” (The Wild Girls, p. 90).

This interest in change as opposed to progress—a distinction that should be of great interest to Front Porch regulars—shows up everywhere in her work. It is most obviously presented in Le Guin’s beautiful rendition of Lao Tzu, which has become indispensable to me. Consider her phrasing of these lines from the Tao’s chapter 57:

The more restrictions and prohibitions in the world

the poorer people get.

The more experts the country has

the more of a mess it’s in.

The more ingenious the skillful are,

the more monstrous their inventions.

The louder the call for law and order,

the more the thieves and con men multiply.

So a wise leader might say:

I practice inaction and the people look after themselves

I love to be quiet and the people themselves find justice.

Lao Tzu seeks to embrace natural change without getting tangled in illusions about our capacity to secure a future in which all our wants will be satisfied or caught up in the confusion of what we want with what is good. It’s about change as the growth of virtue, not the achievement of a social end-state where virtue is unnecessary. (Le Guin translates “tao” as “power,” but notes she would have used “virtue” if the word still carried its old meaning.)

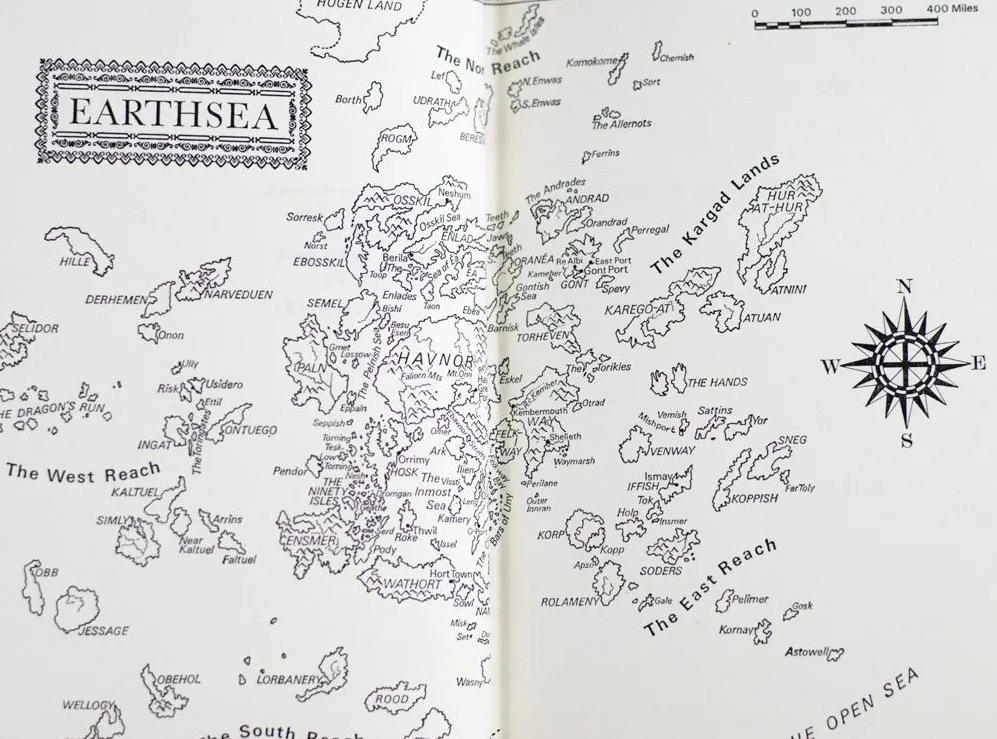

This sensibility is especially apparent in the Earthsea series, which has been called a “Taoist fantasy.” One of the passages that captures it well—and a passage I often return to as I grapple with our response to the pandemic—appears in The Farthest Shore, the third of the five books.

In the story, the wizard Ged must discover the cause of a strange plague which is draining the world of its magic. He travels with a young prince, who will soon inherit the kingdom, along with responsibility for the problem. The boy is struggling to understand what is happening. At one point he asks, “Can it be a kind of pestilence, a plague, that drifts from land to land, blighting the crops and the flocks and men’s spirits?” But Ged says no:

“A pestilence is a motion of the great Balance, of the Equilibrium itself; this is different. There is the stink of evil in it. We may suffer for it when the balance of things rights itself, but we do not lose hope and forego art and forget the words of the Making. Nature is not unnatural. This is not a righting of the Balance, but an upsetting of it. There is only one creature who can do that.

“A man?” Arren said, tentative.

“We men.”

“How?”

“By an unmeasured desire for life.”

“For life? But it isn’t wrong to want to live?”

“No. But when we crave power over life—endless wealth, unassailable safety, immortality—then desire becomes greed. And if knowledge allies itself to that greed, then comes evil. Then the balance of the world is swayed, and ruin weighs heavy in the scale.”

The source of the crisis turns out to be a rogue wizard who’d become obsessed with escaping death and is ruining the world to achieve immortality. Arren’s question (“But it isn’t wrong to want to live?”) captures the common response to any critique of progress (“how could you be against it?!”). And Ged’s answer is wonderfully clarifying. Even his parenthetical listing of the three forms taken by that craving for “power over life” turns out to be a fairly precise taxonomy of the progressive impulse, which as critics such as Christopher Lasch have shown is certainly not confined to one of our two political parties. What does the market-fundamentalist Right want if not “endless wealth”? What does the nanny-state Left want if not “unassailable safety”? (And please observe the accelerating merger of these two under “surveillance capitalism”). Meanwhile, the goal of literal “immortality” may be confined to a few eccentrics in Silicon Valley; but isn’t our whole society in thrall to the ruinous notion that death is a problem to be solved, rather than “a motion in the great balance”?

And yet, Le Guin insists that to give up the craving for “progress” is not to give up hope that humans can help to “right the balance” that we have upset. In her footnote to Tao chapter 57, Le Guin notes that the word she renders “monstrous” is more precisely translated as “new,” and that for Lao Tzu, “new is bad.”

Lao Tzu is firmly against changing things. Particularly in the name of progress. . . . I don’t think he’s exactly anti-intellectual, but he considers most uses of the intellect to be pernicious, and all plans for improving things to be disastrous. Yet he’s not a pessimist. No pessimist would say that people are able to look after themselves.

Lao Tzu’s hopes have a lot in common with ours. “Place. Limits. Liberty.” might as well be the tagline for Tao chapter 80, which Le Guin titles “Freedom.”

Let there be a little country without many people.

Let them have tools that do the work of ten or a hundred, and never use them.

Let them be mindful of death, and disinclined to long journeys.

. . . .

They’d enjoy eating,

take pleasure in clothes,

be happy with their houses,

devoted to their customs.

The next little country might be so close

the people could hear the cocks crowing

and dogs barking there,

but they’d get old and die

without ever having been there.

Many of Le Guin’s stories take place in such a “little country.” Yet her rendition of these little countries and their inhabitants is never utopian. In many ways a radical, she never falls for the radical’s tendency to believe that in the good society there will be no personal conflicts, or all interpersonal problems stem from social injustices. Even in the worlds that seem to capture her ideals, characters struggle with ignorance and arrogance, face heartbreak and misunderstanding, hurt one another, harm their land, misuse their freedom, learn or fail to learn from terrible mistakes.

Often, the story is driven by a character’s discontent with his or her “little country,” with a youthful inclination to long journeys, and with a struggle to balance a longing for “more” with a need for roots. In “Another Story of the Fisherman of the Inland Sea,” Le Guin imagines a culture at once radical (from our perspective) and radically traditional. Family structure, for example, takes sexual fluidity for granted. Two men pair with two women, so the marriage is both heterosexual and homosexual. These are the sorts of story elements that lead readers to mistake Le Guin for a progressive.

But this family structure is not a mark of liberatory progress achieved by breaking with some stifling status quo: it is the status quo. (And to some characters it feels stifling.) The foursomes are not casual flings of the sexually liberated: they are carefully considered life-long commitments, arranged by village elders.

Many other details depict a world that honors permanence. Things and relationships here are built to last: the family home of the main character has been standing for 3,000 years. There is tantalizing mention of a discipline called “thick planning:”

‘farm management’ is the usual translation, but the words have no hint of the complexity of the factors involved in thick planning: ecology politics profit tradition aesthetics honor and spirit all functioning in an intensely practical and practically invisible balance of preservation and renewal.

The main character is a young man who loves all this but believes he would fail himself if he did not leave it for bigger and better things. He becomes a physicist and perfects a new technology that allows for instantaneous travel. He explains it his mother: “A mile or a light-year will be the same. There will be no distance. ‘It can’t be right,’ she said after a while. ‘To have event without interval . . . Where is the dancing? Where is the way? I don’t think you’ll be able to control it, Hideo.’”

She turns out to be right. So Hideo must grow up and out of this “impenetrable self-centeredness of youth” toward a more mature understanding of the relationship between home and journey, order and change.

It’s a perennial theme, of course. Le Guin captures it here, in Hideo’s voice: “The sense of being a bubble in [the village’s] river, a moment in the permanence of life in this house on this land on this quiet world, was almost crushing, denying my identity, and profoundly reassuring, confirming my identity.” Her constant aim as a writer is to show that learning to handle this permanent tension is a matter of “change, not progress.”

Cherish Tradition

For Le Guin, the proper context for discovering and grappling with that tension is always a particular culture, a way of life, a “tradition.” Traditions in Le Guin’s stories are presented with a rich ambiguity that helps preserve her readers (many of whom are young people) against their own adolescent impulse to equate “old” with “oppressive.” For her, what is old is the same as what is new. In both there are bad parts, there are good parts, and our human task is to sift, to make distinctions and avoid generalizations. Our work is never done: we do not make progress toward its completion. Instead, to take up the work is to be changed.

At the same time, one of the good parts about what is old is the fact that it is old. This is the insight that makes me willing to call Le Guin not just a thoughtful person but a certain kind of “traditionalist.” She holds on to that ancient notion of virtue, the notion made strange in a society that believes, with Michael Oakeshott’s Rationalist, that “to form a habit is to fail.” (Or, as one of my most Rational students frequently insists: “tradition is stupid.”)

The traditionalist believes on the contrary that familiarity, the sense of being at home with one’s thoughts and actions, of being habituated into a “second nature,” is its own essential ingredient in the good life. It is not enough to “do the right thing.” The good life depends on being consistently good at being good and on enjoying one’s own growing skill in that art. And this habituation takes place within a particular tradition. It requires a community extending over time that teaches those skills and provides the context for their enjoyment. As she puts it:

The beauty of your own tradition is that it carries you. It flies, and you ride it. Indeed, it’s hard not to let it carry you, for it’s older and bigger and wiser than you are. It frames your thinking and puts winged words in your mouth.

The tricky question for the traditionalist always comes when the skill that you’re supposed to learn from your tradition is the ability to question and challenge your tradition. How does this work, exactly? What are the grounds for your criticism? Don’t we have to step outside the tradition and become “Rational,” if we want to accomplish that sifting of good from bad? In which case, doesn’t all the good of a tradition come from it’s being good, and none from it’s merely being old?

That’s the line of thought that becomes the progressive mind (which tends to suppose conversely that one of the good parts about progress is that it is new, dismissing Lao Tzu’s claim that “new is bad”). Le Guin avoids it by making what I think of as a MacIntyrean distinction between a dead and a “living” tradition, though she doesn’t make this distinction in the explicit way of a philosopher, of course. As a storyteller, she is helping to keep a tradition alive, by telling stories that let it change.

Here is where Le Guin begins to speak as a woman and to make an effective feminist criticism of a male-dominated tradition that avoids the usual mistake of concluding that in light of such criticism, “tradition is stupid.” The passage quoted above appears in her essay “Earthsea Revisioned,” where she reflects on the thematic developments that take place between book one, which follows a conventional male hero, and the last, which sees the famous hero humbled by the loss of his conventional power and a forgotten girl made fiercely powerful but in an unconventional sense. (Once again, many readers notice these themes and read a certain political sensibility into the author.) That passage, lauding the “beauty of tradition” which “carries you,” continues in a way that helpfully complicates the insight:

If you refuse to ride, you have to stumble along on your own two feet; if you try to speak your own wisdom, you lose that wonderful fluency. You feel like a foreigner in your own country, amazed and troubled by the things you see, not sure of the way, not able to speak with authority. It is difficult for a woman to speak or write with authority unless she remains in a traditional role [because] [a]uthority is male.

Yet she has no regrets about having been “carried” by this tradition.

I look back and see that I was writing partly by the rules, as an artificial man, and partly against the rules, as an inadvertent revolutionary. Let me add that this isn’t a confession or a plea for forgiveness. I like my [earlier] books. Within the limits of my freedom, I was free: I wrote well; and subversion need not be self-aware to be effective.

Furthermore she remains loyal to the tradition’s old idea, cherished by Virginia Woolf, that “[a]rt was to transcend gender.” She (and Woolf) remain loyal despite the way some use that idea to cover the tradition’s obvious failure to live up to it. “To me it is a demanding, a valid, a permanent ideal,” she insists. Le Guin would not be among those who conclude from the fact that the founders enslaved people that their claims about freedom and equality are false.

She is speaking in these passages of the literary tradition in which she wrote Earthsea. At the same time she is speaking of the fictional tradition of magic that anchors Earthsea’s world. The books celebrate those traditions, along with the institutions that preserve them, and implicitly criticize them for what they have excluded. But that criticism never conflates the virtues and vices of specific characters with the injustices of the structures they work in, even as it shows how individual virtue and institutional structure are connected. In other words, she never reduces an individual to a social location, despite being fascinated by the great variety of social locations. In the essay she says “[a] rule may be unjust, yet its servants may be just. At the University Virginia Woolf could not enter, Tolkien taught. The mages of Roke [the wizards who hold authority in Earthsea] were honest and just men, trying to use their power mindfully.”

Call Things By their Right Names

The key to the working of magic in Earthsea is the knowledge of “true names.” The idea that every person and thing in the world has its “true” name (as opposed to its “common” one), and that knowledge of the true name gives the knower power over the person and thing, is not original to Le Guin. It is an old trope, present in many myths and stories (Rumplestiltskin, for example). But it is not just a fun way to embellish a rollicking adventure, at least not as Le Guin employs it. She is making a morally serious point about life in the real world.

Although as a Taoist she would put it differently (and the difference matters, as I note below), this point is akin to the Confucian “rectification of names.” In Analects Book VIII, Confucius says:

A superior man, in regard to what he does not know, shows a cautious reserve. If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success. When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish. When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded. When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot. Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect.

Here, the idea of the “true name” has nothing to do with magic. It is not a piece of mysticism, if by that we mean what Le Guin, in her afterward to the Tao, calls “squishy-mindedness.” Rather it is about precision, and the moral importance of it. (Le Guin warns Lao Tzu’s readers against the common “confusion of mysticism with imprecision.”) Calling things by their right names is about our responsibility to the world around us. The whole point is that we do not get to make it up. There is an objective truth. We are responsible for speaking it as best we can, and for acknowledging our fallibility as speakers.

In an essay called “Dreams Must Explain Themselves,” she puts the point back into Taoist terms, which push against the Confucian belief the that this work of rectification should only be undertaken by authorities and authoritative institutions: “The Taoist world is orderly, not chaotic, but its order is not one imposed by man or by a personal or humane deity. The true laws—ethical and aesthetic, as surely as scientific—are not imposed from above by any authority, but exist in things and are to be found—discovered.”

Of course we make these discoveries by making use of a particular human language. And this means participating in a linguistic community with a history—in other words, a tradition into which we are educated, along with its institutions. (In Earthsea, the mages must study for years to learn by heart the true names that give them power over—and responsibility for—the world around them.) When the wizard Ged is in training, one of his teachers sums it all up like this:

The Master took [the pebble] and held it out on his own hand. “This is a rock; tolk in the True Speech,” he said, looking mildly up at Ged now. “A bit of the stone of which Roke Isle is made, a little bit of the dry land on which men live. It is itself. It is part of the world. By the Illusion-Change you can make it look like a diamond—or a flower or a fly or an eye or as a flame—” The rock flickered from shape to shape as he named them, and returned to rock. “But that is mere seeming. Illusion fools the beholder’s senses; it makes him see and hear and feel that the thing is changed. But it does not change the thing. To change this rock into a jewel, you must change its true name. And to do that, my son, even to so small a scrap of the world, is to change the world. It can be done . . . But you must not change one thing, one pebble, one grain of sand, until you know what good and evil will follow on that act. The world is in balance, in Equilibrium.

Berry’s essay “Standing By Words” (which also draws from Analects) makes a similar argument in prose. His theme is “the accountability of language—hence . . . the accountability of the users of language.” He says that “in order for a statement to be complete and comprehensible three conditions are required:

1. It must designate its object precisely.

2. Its speaker must stand by it; must believe it, be accountable for it, be willing to act on it.

3. This relation of speaker, word, and object must be conventional; the community must know what it is.

When people fail to use language in this way, they are usually “taking more power than can be responsibly or beneficently held.” The sign of a broken language will be its “inability to admit what it is talking about.” It will hide its bid for unaccountable power behind technical jargon that pretends to present only the morally neutral facts; or behind emotive talk that claims only to express purely subjective feelings which are supposed to be considered “valid” but not accountable to any standard of validity.

This problem should feel even more familiar now than it was when Berry wrote about it in 1980. The demand for progress, the critique of tradition, and the quest to rectify the names have rapidly intensified, especially of late. It is becoming increasingly difficult to talk with anyone who disagrees with us about, say, the proper referent for the word “woman,” or what “racist” signifies.

Though I hesitate to speak for the dead, Le Guin might sympathize with many of the avant garde Left’s most ambitious initiatives in these domains. She may not be a “staunch progressive,” but she is certainly some kind of radical. But that’s just it: there are different kinds of radical. Jedediah Purdy describes the essayist George Scialabba as a rare creature: the “radical democrat” who “also demonstrates the actual virtues of conservatism—the deeply felt love of the best that has gone before, of what makes the world knowable and habitable.” In this sense, “radical conservative”—or perhaps “conservative radical”—might be an accurate label for Le Guin.

Concluding Thoughts

There’s a healthy variety of opinion among us. I suspect some porchers would disagree with Le Guin on important issues, especially sex and gender, and would depart from Le Guin’s general outlook in other ways as well. For example, while many here are religious, she is “irredeemably secular” (but also, and intriguingly: a “secular puritan”).

The reason I think she is very much worth reading, and the reason I hope that she’ll be welcome on the Front Porch, is that for all the reasons explored above, it is possible to talk with her about those disagreements. She and I share a sensibility that runs deeper than any of the disagreements I can imagine having with her. It’s a sensibility that roots such disagreement in a shared pursuit, not of “facts” and not of “feelings,” but of objective values that comprise “the good life.” Such values are permanent but must be discovered and rediscovered and rightly named by inhabiting a time-bound tradition, even if that tradition has often obscured those same values, and must be corrected by further rectification.

Recovering and rebuilding a language of moral objectivity, which is always also a language of moral fallibility, is in my view the most important cultural work we can be doing right now. It’s a work that needs to be done within and across many different political or ideological camps, because it’s not just one side that’s been hamstrung by the shattering of our moral vocabulary. In this context, it’s always good to encounter a figure from another side who not only shares that goal of recovering and rebuilding a moral language, but whose stories can actually help shape us into more skillful speakers and more effective “rectifiers of the names.”

3 comments

Michael Serafin

I am a 60-year-old geezer. I have been conscious of Mrs. LeGuin’s work for most of my reading life, but I have never read her. I think that one needs a level of maturity and lived experience in order to understand and appreciate her work. Mr. Smith’s splendid appreciation makes me believe I am finally ready to read her now.

Martin

Thanks, Adam, for a superb essay that thoroughly explores several themes. My first encounter with Ursula LeGuin was in high school 50 years ago, when Left Hand of Darkness was recommended to me. I was surprised midway to discover that the hero on a snowy world had dark skin. This was part of LeGuin’s genius, or at least part of her style: a casual revelation that suddenly dispels reader expectations.

A few years later, I read the original Earthsea Trilogy, and still later Lathe of Heaven, which was the first of her works to be made into a full-length movie. The “solution” to racism imagined by the hero of the latter book was that all people had gray skin — a strong LeGuin hint that a simplistic view of uniformity is not the same solution as mutual respect for differences.

I definitely agree with your stance and evidence that LeGuin favored change without being a progressive. I would argue, though, that “progressive” is now, and perhaps always has been, a term that denotes a vision of a predefined future that will have better morals, material wealth, whatever, than the world we currently live in. In fact, this notion of “progress” towards a fixed ideal is a concept common to fundamentalist Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and other religions, all of which believe that humanity inevitably will move toward their respective visions of the moral high ground.

I have not read her version of the Tao Teh Ching, but I assume it is an interpretation of at least one translation of the original Chinese. Regarding chapter 57 that you quote, her use of “con men” is perhaps a leftist criticism of rightist law and order. A different view would be akin to Harvey Silverglate’s Three Felonies a Day, which is a libertarian statement that seems closer to the Taoist truism “the more rules you have, the more rule-breakers you will naturally have”.

I also question your unsubstantiated claim that her use of “monstrous” is based on a Chinese word that simply means “new”. Waley’s 1934 translation uses “cunning” while the 1981 translation by martial arts master Tam Gibbs uses “bizarre (unorthodox)”. Clearly there are multiple nuances possible surrounding the generic concept “new”.

Gibbs’s translation of the text includes a translation of lectures given by grandmaster Man-jan Cheng, whose comment on #57 is rendered “The more sharp weapons the people have, the more skilled as artisans they become, and the more precisely the laws are articulated, then the more thieves and outlaws will proliferate.” I’m reminded here of a remark in Hernando De Soto’s book The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else: laws work best when they follow customs, not the other way around.

Going back to Adam’s insight that tradition and change can go hand in hand, I’ll close this long comment with an apocryphal tale recounted by Cheng in the preface to Gibbs’s translation Lao-Tzu: “My words are very easy to understand.” After Confucius explained his vision of humanism and justice, Lao Tzu replied, “What you, sir, have spoken of today is like a footprint. That which made the footprint has gone, and how, alas, can the print be taken for the foot?”

Perhaps LeGuin’s viewpoint can be understood as a deep recognition that beneficial change is an attempt to recapture an ethos that was once so deeply embedded that it was unspoken. What we strive for today is not “progress” toward a predefined moralistic endpoint but a reawakening of an earlier vision of unity that can now be expanded beyond racial boundaries.

Justin Patrick Moore

Great article. I’m really happy to see Ursula, a true American master and original, having a spot here on the front porch. I do hope she stay’s a for spell and sits awhile.

I see this conversation starting here about Ursula as being similar to the one Wendell Berry enjoys with Gary Snyder. I like Gary as much as I like Wendell. They have a lot of interests and goals in common, though both are different as well. And I know that Ursula would have a lot in common with Gary too. (I wonder if they ever met, both being up in the Pacific Northwest? -A quick search on the metanet reveals they have in at least one joint discussion)

This post gives many great themes for further meditation and reflection, thank you Adam for writing this.

Comments are closed.