Livingston, MT. In his essay, “Faith in Fiction,” from the August 2013 edition of First Things, Canadian born Catholic writer Randy Boyagoda famously lamented the tired recycling of the same 19th and 20th century authors:

I’m sick of Flannery O’Connor. I’m also sick of Walker Percy, G. K. Chesterton, J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, T. S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Dostoevsky. Actually, I’m sick of hearing about them from religiously minded readers. These tend to be the only authors that come up when I ask them what they read for literature.

Although Boyagoda notes that these writers, “brilliantly and movingly attest to literature’s place in modern life, as godless modernity’s last best crucible for sustaining an appreciation of human life’s value and purpose that corresponds to our inherent longing for the good, the true, and the beautiful,” the Catholic Sri Lankan author and University of Toronto English professor further complains that these authors are all “dead” and thus do not speak to us as a contemporary with his or her finger on the pulse of what has been called the “postmillennial era.”

Randy Boyagoda’s piece eventually morphs into a panegyric on the work of contemporary Jewish novelist David Shields, who, Boyagoda argues, “offers a polemically narcissistic, aggressively atheistic vision of how and why literature should matter to us, premised upon the willfully inward, selfish turn that follows from rejecting God and religion.”

However, “Faith in Fiction,” even seven years after its publication, still leaves an open-ended conundrum for Christian readers and writers: who are the great Christian writers of our time?

In “Faith and Fiction,” Boyagoda mentions the (now deceased) Anglican poet Geoffrey Hill as well as the Calvinist novelist Marilynne Robinson as examples of intelligent and serious contemporary Christian writers. These authors are primarily noted for their treatment of modern and postmodern struggles with belief. Hill and Robinson are both very much in dialogue with Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment intellectual and existential challenges to Christian faith.

What has been missing in Christian fiction is an Anglophone writer who speaks the language of the postmillennial era, of the period in Western history in which the great evils are not the Holodomor or Antietam, but rather school shootings and pornography addiction.

I can think of at least one Christian writer who has established himself as a prolific author of both scholarly material as well as of short stories and poetry (including many poems published within the pages of First Things), and whose writing in all these genres engages the strange combination of listless fatigue and hummingbird hysteria of the digital age: Joshua Hren.

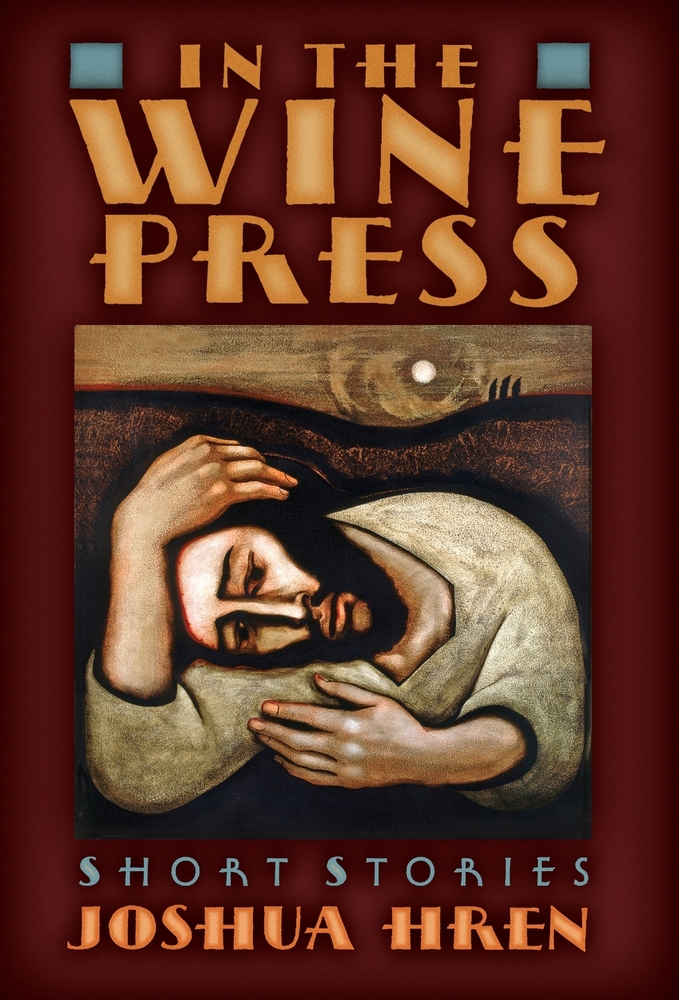

Assistant director of the Honor’s Program at Belmont Abbey College, Hren has a new collection of stories from Angelico Press. Titled In the Wine Press, it presents itself as a quintessentially postmillennial Christian work that truthfully engages the agony so many Christians feel in our current era.

In the Wine Press gathers together a host of rough-edged stories of American Christians living in the rise and fall of both Evangelical Catholic and Protestant American Christianity, which arose in the twilight of the Clinton era and peaked during the confluence of religious fervor and patriotism under the White House of George W. Bush.

With John Paul II on the throne of Peter, Rick Warren at the helm of Saddleback Church, and W. in the White House, conservative American Christians experienced a sense of political and social triumph. Grounded on (the conservative Catholic reading of) the Second Vatican Council and the creation of what the then Pastor Richard John Neuhaus had called the “new religious right,” this movement had finally come to fruition.

As the Iraq War drug on and the 2008 economic crisis erupted, however, followers lost faith in many of the political tenets affiliated with these movements. Moreover, the explosive revelations of the 2002 Boston Globe Spotlight scandal revealed that clerical abuse was not an isolated or marginalized phenomenon.

This chaotic and amorphous era is marked simultaneously by a tired and cynical religious skepticism as well as a fanatical, “post-ironic” uncritical dedication to violent political causes fought among the ruins of Christendom. It is within this post-absurdist (that is, an absurdism that is no longer aware of itself as being such) framework that Joshua Hren crafts the stories of In the Wind Press.

The attempt of the laity to cope with the fallout of the clerical abuse scandal and the cover up by the Catholic hierarchy is the subject of both “Tears in Things” and “Work of Human Hands.” “Work of Human Hands,” which tells the story of a single, Hindi-American mother’s attempt to wrestle with her anger at a priest who had abused her son as well as the priest’s own attempts at repentance, is the strongest story and thus the emotional and intellectual touchstone of the collection.

Hren skillfully chronicles the mother’s mixture of pious devotion, desperate love for her son, anger at the priest, and recrudescent Hindu religious roots. It is this tremendous ability to provide a potent and multilayered panorama of the thoughts and feelings of a wounded “post-post-modern” (yes, there is such a term) Christian that is Hren’s strong point.

Within In the Wine Press, Hren deals with a host of other postmillennial American problems. The grotesque and farcical character of the contemporary American political landscape sets the theme of “Darkly I Gave into the Days Ahead,” which tells the story of a high school teacher’s encounter with the small but sharp fangs of the bureaucracy of a Catholic school system promoting a rally for an outlandish politician. In stories such as “Horseradish” and “Old Blood,” Hren chronicles people living among the wreckage of those Midwestern communities produced by what Michael Novak famously called the “ethnic Catholics.” These stories (and others in the work) stand unique among contemporary literature for their depictions of the hardships of married and family life while at the same time not attacking or denigrating marriage and families themselves—“Sick at the Thought” narrates the profound effect pornography use can have on a marriage and family.

Joyce, Faulkner, and David Foster Wallace heavily influence Hren’s writing, which flows with the cacophonous rhythm of the postmillennial mind conditioned to wildly chase social media feeds. However, there are stories, such as “Horseradish,” in which Hren’s writing takes a more mellow and ruminative pace, echoing the thoughtful and carefully wrought “in the character’s head” prose of Cormac McCarthy. Throughout, Hren’s (almost) stream-of-consciousness is that of a thoughtful Christian, not a Melvillesque American nihilist and carries with it an existential seriousness that is as redolent of St. John of the Cross as it is of Samuel Beckett.

It is difficult to measure good writing without retreating to vagaries of language and impressionistic exclamations that reveal more about the taste of the critic than about the quality of the prose—a phenomenon which, with apologies to Randy Boyagoda, T.S. Eliot identified as one of the central frustrations of writing about literature and art. Nevertheless, Joshua Hren’s In the Wine Press is a work that burrows into the unhappy mess that is postmillennial American Catholicism and does so with an honesty and seriousness that few writers have attempted or, for that matter, are capable of attempting.

As with the writings of Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy, one of the troubling elements in Hren’s work is that the numinous signs of grace scattered throughout his thirteen short stories are so fleeting that the narratives seem overwhelmed by despair. (Some readers gifted with what the poet called “a chaster muse” might object to a couple of passages in the collection in which Hren—albeit circuitously—attempts to delineate the horror of abuse.) Nonetheless, as Cardinal Newman noted, Christian literature, literature that presents hope and salvation for mankind, is a difficult task: Even though men are capable of great deeds, which can be chronicled by heroic works of literature, men and women are much more often weighted by sin, and because the “lot of men is sinful . . . literature cannot show them otherwise.”

1 comment

Rob G

I have Hren’s first collection but have not yet read it. I might take a look at this new one first.

For my money the contemporary “Christian” writer I find most vital is ironically enough not a Christian but a Jew — Mark Helprin. He manages to combine a certain postmodern irony with an old-fashioned concern for craft and a deep interest in the virtues: the Coen Bros. minus the flippant nihilism. I’ve long felt that Helprin’s brilliant baseball novella, “Perfection,” would make a perfect Coen Bros. movie if they could manage to drop the misanthropy for a couple hours. I don’t know anyone other than Helprin who could combine a hilarious romp about a Hasidic teenage baseball star with a very moving meditation on the Shoah.

I’ve been reading him for years, but he has come to represent for me a sort of anti-Houllebecq, “Anti” here not meaning “against” but opposite. Helprin’s recent work seems to me to be offering a similar cultural critique to that of Houllebecq, but without either the vulgarity/horror or the hopelessness.

Comments are closed.