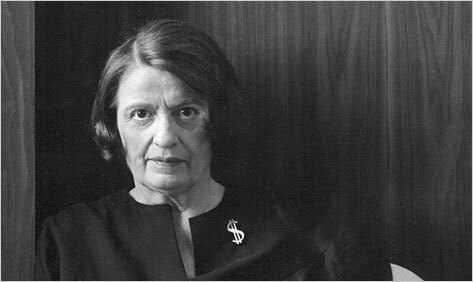

Cleveland, OH. Who is Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand is synonymous with a vulgar strand of American libertarianism or conservatism, a combative and muscular individualism with a near slavish pedantry for “capitalism” (however conceived). Aaron Weinacht, in his new book Nikolai Chernyshevskii and Ayn Rand, challenges this popular misconception. Locating Ayn Rand’s intellectual foundation in mid-nineteenth century Russian nihilism and egoism, especially in the writings of Nikolai Chernyshevskii, Weinacht’s thesis asserts that while Rand became a child of America, she remained—intellectually and ideologically—a daughter of Russian radical nihilism.

Individualism, admittedly, is an often-abused term. Collectivists who fancy themselves the heirs of Marx and Lenin and others use it as a pejorative for bourgeois capitalists and their ilk; yet they often fail to recognize an intrinsic strand of individualism also embedded in Marx and leftist ideologies that grew out of the ideologies of the mid-nineteenth century aspiring for freedom and liberation from “The System.” Individualism has also become a whipping boy for neo-traditionalists blaming individualism for the desecration of community and family, the strong pillars of society in their romantic imagination. To Rand, however, individualism is synonymous with the egoist-radical dream of progress and utopia, freedom and liberation—ideas that historically emanated more from leftwing radicalism in late Enlightenment Europe than the economic theories of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Frédéric Bastiat.

Russian nihilism was a particular outgrowth of the individualist, ego-centric, philosophies of Ludwig Feuerbach and Max Stirner which asserted the agency of the individual to throw off the shackles of any “system” that was holding the individual back from progression: material or intellectual or spiritual.

Nihilism, here, isn’t about the absence of values but about the destruction of the existing order to create something new, and better, out of its ruination. It entails a liberationist view of progress: to be liberated from social and institutional systems was to be free. In that freedom, individuals would discover their agency and ascend to create new values, new loves, new happiness, and thereby become the man-god. Despite disparaging Christianity and Platonic mysticism, there is an ironic—though inverted—inheritance from the very intellectual currents they despised: the striving to heaven and the metamorphic nature of man are not new to the nineteenth century but ideas inherited from Platonic Christianity subsequently divorced from their overarching metaphysical “systems.”

Weinacht believes that a close comparative reading of key Russian nihilist literature reveals their influence on Ayn Rand: “Numerous common themes emerge. These include egoism, rejection of original sin, emphasis on the human will with its heroic capabilities and creative impulse, the relationship between freedom and necessity, emphasis on youth, the nature of negative emotions such as blame, guilt, jealousy, and envy, the God-man verses man-God problem, and the treatment of love, sex, and relationships.” All of these are contained in Rand’s magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged. Per Rand’s own admission, her philosophy of “rational egoism” amounted to the belief that “the highest moral purpose of a man’s life is the achievement of his own happiness.” In other words, the individual alone—free from everyone and anything—is the decider of his own happiness.

This is what Atlas Shrugged is about: the nihilist desire to achieve one’s own happiness against a stifling system and order that tries to prevent it. Atlas Shrugged, in Weinacht’s assertion, isn’t about capitalism and free markets at all—insofar that these issues may be included, they’re only secondary and peripheral rather than axiomatic. After all, John Galt lives an austere, simplistic, lifestyle despite his grandiosity as investor and captain of industry.

Who is John Galt? John Galt isn’t the bourgeois capitalist par excellence. He is the Russian nihilist par excellence dressed up in Rand’s marriage of the Russian nihilist tradition with American economic materialism. Galt’s new motor threatens the established order. The government and its bureaucracy, as well as the public at large, hold Galt and the new world he is creating back. The struggle is dialectical.

The heroic creative principle within Russian nihilism centers on the ability to make possible the impossible. The heroic individual, in Russian nihilism, is the man who is different and misunderstood, the man who wills his own will to create and usher in a new world. In this respect, so many of the other great figures of Russian literature are nihilists who either embrace this heroic desire to tragedy and self-destruction or reform themselves away from their earlier naivety (depending on whether the Russian author is an ideologist for nihilism or responding to nihilism’s shortcomings). One can think of Raskolnikov, Pierre Bezukhov, and Pasha Antipov as examples.

Galt, then, isn’t Rand’s heroic reimagination of Our Lord Henry Ford but an Americanized iteration of Rakhmetov or Vera Pavlovna of Chernyshevskii’s What Is to Be Done? (Or just an Americanized iteration derived from the long list of literary Russian heroic nihilists.) He is the man-god upon whom the better world of tomorrow hinges. His will destroys the old world and begins the construction of the new tomorrow and leads to the metamorphic transformation of rational man into deity.

Rand, being a disciple of Russian nihilism, therefore casts Galt as a heroic figure rather than a tragic one. But being the man-god, he is misunderstood. As a threat to the existing system (in Atlas Shrugged, the system is the burdensome soft tyranny of the bureaucratic state), he is directly opposed by those who benefit from the existing system. Yet Galt’s heroism and genius attracts followers: namely Hank Rearden and Dagny Taggart.

In Weinacht’s reading, this seems to be the more salient issue for readers to understand. We are not John Galts. We may, however, be able to “convert” and become followers of the new creative liberation offered by their heroism. We can be Hank Rearden and Dagny Taggart and partake in the New Eden that the John Galts of the world create.

For a movement that sought to throw off the shackles of “original sin” and mystical religion, Russian nihilism ironically embraced original sin and mystical utopianism. For what is original sin? As Saint Augustine wrote in The City of God, it was Adam and Eve’s choice to will for themselves their own happiness, to reject “the system” of nature God created for their happiness. That is the exact ideology proclaimed by nihilists: we decide and will for ourselves our own happiness. Why is the nihilist a hero? He immanentizes the eschaton and brings a new world of freedom and liberates us from the oppression and injustice of the current world. He realizes the hope of mystical religion from Antiquity to the present.

Aaron Weinacht’s book is a needed corrective to the public misperception of Ayn Rand as radical capitalist. She was, first and foremost, a radical nihilist. Insofar as she embraced capitalism, it was secondary to her axiomatic nihilism embodied best in John Galt.

Sadly, this book suffers from being a very niche work for an incredibly niche audience. This is unfortunate as the work is enlightening on many accounts. Who might find it of value? I’ll offer my pitch to many potential readers. Lovers of literature might find new insights into literary analysis in reading the book, and it can be useful for anyone with proclivities toward nineteenth century Russian literature (as I have) and therefore help bring new insights to the writings of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and even Pasternak. Philosophers and theologians may find the work helpful in tracing the intellectual currents and debates that influenced Russian thinkers and writers in the nineteenth century and beyond. Historians may also find the book useful in offering a new and concise overview of the complexities of Russian nihilism, its origins and key tenets, and its debates with the currents of Russian intellectual life in the mid-nineteenth century. As for me, after reading Weinacht’s book I’ll never read, or explain, Atlas Shrugged the same way again. I remain, of course, no disciple of John Galt and, therefore, Ayn Rand. Give me Dostoevsky’s Myshkin instead.

2 comments

Aaron

Hey, David: thought I’d clarify a point re: my book. Yes, Rand was a teenager when they headed for southern Russia, but she didn’t actually leave Russia till she was in her early 20’s.

Per your final paragraph: nicely done. I concur wholeheartedly.

Aaron

David Naas

An interesting thesis, which is worth consideration. But she was a young teenager when her family fled the Bolsheviks. And while she may have been precocious (which I, frankly, doubt) one must ask if she had already absorbed theoretical nihilism as claimed.

My own introduction to Rand was literally sophomoric, as a classmate began spouting Randian thoughts in our Sophomore year of college. I read her popular books, Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, of course, as well as some others, looking in vain for a “there”. I never found it.

What I did find was that, despite her self-serving claims to Aristotelian discipleship, she was really still a Bolshevik in her understanding of capitalism, and a poor-man’s misunderstood Nietzsche in all else. As years went by, and exposes duly arrived in the bookstores from her former associates, that perception was not altered, except to note how blatantly hypocritical it all was.

But religious cults need not blush, as political and philosophical cults have it all over them for willful blindness and groupthink. And eventual disintegration. Such was the unlamented fate of “Objectivism”.

Comments are closed.