Boise, ID. Talking Cure by Paula Marantz Cohen is not about Freud’s theory of the cure for anxiety, despite taking its name from that theory. Nor is it, as the subtitle proclaims, precisely about the “Civilizing Power of Conversation.” Instead it is a love letter to the many joys of conversation and, like most love letters, is too personal to be universally intelligible, and too descriptive to be philosophical. Who ever read a love letter and fell in love with its object?

With its discursive forays into personal experiences, the novels of Jane Austen, the history of the cafe, and the pleasures of food and drink, Talking Cure ought to be quite satisfying, for I too love a good conversation and believe it to be a foundational element of a healthy life and a healthy society. Unfortunately, for me at least, it falls a little short of the transcendent magic I was hoping for. Cohen offers a glimpse of what good conversation means and requires but the middle chapters descend into mere description that fails to fully consider the implications of those meanings and requirements.

In ten chapters, Cohen explores why and how to converse, the definition of conversation, conversation around food and drink, conversation among the French, various notable literary and political groups and their reputation for conversation, the portrayal of conversation in novels, conversation in academic contexts, and conversation in the age of digital connection. The book is part essay, part memoir, part panegyric.

Cohen came “from a family of talkers” but is sensitive to the possibility that her response to that noisiness could have been rather different than the eager participation she enjoyed. Her parents’ different styles of conversation receive their share of praise as she examines how the family both shapes us and also becomes a closed system that we must escape if we are to truly converse as adults. “To speak to the converted or the entirely familiar is not to truly converse,” she says. It is here, in her introductory passages, that the magic of good conversation is best delineated. Without difference “we simply mouth platitudes of agreement” and are forced to “harbor the secrets of our individual natures within our own breasts.” To be fully human we must “share who we are, in our essential uniqueness.” Such a description resonates, but it also issues an implied imperative that Cohen does not pursue in the rest of the book.

If difference and change, in conversation as well as other aspects of life, are both necessary and frightening, then we have an obligation to confront this need in some serious and courageous way. If “talk with others allows us to practice uncertainty and open-endedness in a safe environment” then we actually need it individually and collectively. However, instead of pursuing the metaphysical implications of these imperatives, Cohen shifts to descriptive appreciation of various contexts for conversation. It is this shift that takes most of the air out of the “cure.”

In her “Food, Drink, and Conversation” chapter, Cohen recounts Virginia Woolf’s contrast between the men’s dining hall at “Oxbridge” and the greatly inferior women’s dining hall in the same vicinity, and yet all the implications of conviviality, joy, nourishment, and welcome, are left muddled and contradictory. Woolf is both right and wrong in Cohen’s retelling, but how and why is left unexplored. In her descriptions of different food and drink she seems to be saying that food and conversation are related, but how and why is left unclear. Is conversation mental nourishment and is there a parallel between reading alone/thinking alone and eating alone? Is it a matter of personality or of internal or external variety? Is food metaphysically the appropriate vehicle for interpersonal understanding? What of the traditional protection of bread and salt at a host’s table? Is it simply that the physical comfort of good wine loosens the tongue and the soul? Or that the generosity of sharing food prompts generosity of thought? We are left to start these questions on our own.

She describes the French as loving contrast and contradiction, but does not go beyond the immediate description of how a dramatic dichotomy can stimulate talk. Indeed it can, but what does that mean for the kind of implicit homogeneity of most of our social circles? Why does easy contradiction work so well for generating talk? Does it conceal deeper difference or reveal complexity and bring disparate people together? Cohen does not explore this, leaning instead on fond memories of her time in France and the pleasures of lighting a cigarette while formulating a thought. She does offer some consideration of why the French are as she characterizes them, but these flickers of historical detail are not entirely convincing and raise factual questions more than philosophical.

Her chapter on famous conversational groups (Dr. Johnson and his friends, the Bloomsbury group, the expats of Paris in 1920s, Harlem during its renaissance) is fully descriptive. Each of the groups portraying some way that conversation might inform, motivate, or inspire an individual or a movement. As a postmortem of her intellectual influences, they are intriguing. Once again, however, the reader cannot determine from these descriptions the blessings or the limitations of good conversation. Cohen does explore some of the potential negative aspects of these groups (Are they quite as witty as they described themselves? Does too much talk dissipate intellectual energy? Does being a good conversationalist preclude being a good artist?) but the implications for the Talking Cure are not explored.

In the second-to-last chapter, Cohen addresses the conversational context of the college seminar. Here she offers the fruit of her experience as a teacher and as a student and returns to the meanings and implications of good conversation. In a really good seminar discussion, the “flow” state of pure creativity lends a sense of significance, intimacy, and joy to all the participants and Cohen is as enthusiastic about this as she is realistic about the difficulty of achieving it. Her descriptive emphasis is well-deployed here as she tells of the healthy tension between making a classroom welcoming as well as challenging, or as she recounts the way that a good seminar leaves the classroom behind and transforms the coffee shop, the bar, and the dorm room into sites of intellectual development.

In Cohen’s description of seminar conversation, I recognize my own experiences as a teacher and as a student. Her enthusiasm tempered by realism does not mislead the reader into expecting either too much or too little from a good academic conversation, and she helpfully delineates the many ways a seminar can go wrong in order to understand how it can go right. And perhaps this descriptive turn is helpful to some; perhaps it can help someone imagine having and enjoying better and deeper conversations; perhaps it could prompt some of that exploration. I find it a bit thin, too much setting of the scene and insufficient, well, conversation, about conversation. “The need for conversation is one that many people have not fully acknowledged, perhaps because they have not had occasion to do enough of it or to do it well.” Still, it seems that deeper reflection would be just as winsome, if not more, and would be more helpful for spurring the reader to pursue good, solid, enlightening conversation, as a fundamental part of the good life.

Cohen’s early reflections on good conversation that exhort the reader to be cautious of treating the other as an object, that point out the numinous sense of gift in a free and thoughtful conversation, that observe the sense of affection and trust that can grow in it, should stimulate the conversational appetite. But it must be fed on thicker reflections and nourished in sturdier environments. You don’t need Paris, The Literary Club, Socrates, or Gertrude Stein. You do need friends, serious ideas about things that matter, consistency, and a cozy atmosphere (whether it is in a dining room, a library, or on a front porch!) You must have enough self-confidence to speak, but that isn’t much (just a little nerve) if you have friends you can trust. Confident or shy, you must be open, open to being wrong, open to new ideas, open to a distasteful explanation, open to changing your mind. Openness requires humility, true humility of the self-forgetful variety, humility that will discipline you to learn but also require you to teach.

Meandering small talk has its place, but it does not engage the human soul fully and cannot be the main course. Any conversation worthy of the name has to engage a person’s intellect, moral sense, and their virtue. In order to change a person the conversation has to be fundamentally challenging, an adventure; a difficulty and not a rest. If the conversation is not wrestling on some level with something genuinely ultimate then it is simply entertainment and not the cure for anything.

Perhaps this reveals, then, the limitation of a book about conversation. One cannot really have a book about conversation alone. Conversation is so much a fruit of individual persons and their relationship to one another, that a book about that fruit must be one about how to become a deeper, better, more complex and interesting person. And that is a lot to ask of anyone. I need all of literature, all of the correction and guidance of my religious commitments, all the encouragement of my spouse and my friends, all the sensitivity of conscience to do that. And that is a lot to ask of a book.

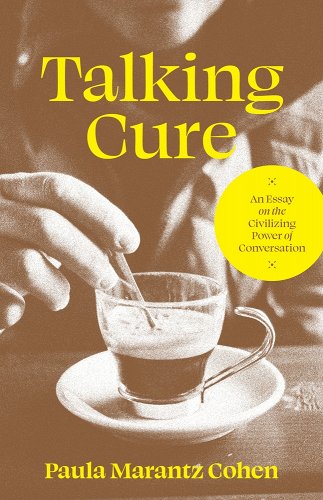

Image Credit: Jean Béraud, “Au Café” (20th c.)