In recent years, there has been a revival of interest in anti-trust policy in the United States. Scholars like Tim Wu and Matt Stoller have released summaries of the history of anti-trust action in America, the United States Congress has held hearings inquiring into anti-competitive practices by major corporations, and several large mergers (or attempted mergers) have brought the salience of anti-trust law back into the public eye.

Though the Republican party has, in the past, been predominately pro-business, which means pro-big business in practice, there have been flashes of anti-corporate and anti-trust sentiment on the American right during this period. Recently, The American Conservative ran a series of articles on the origin of lax anti-trust enforcement, additionally arguing that it is now time for an anti-monopoly movement on the right in America. Senators like Josh Hawley and Mike Lee have joined their Democratic colleagues in expressing deep concern over the actions of corporate tech giants, sometimes in response to what is viewed as censorship of Republicans and conservative ideas, but sometimes over corporate power in the abstract, wielded broadly and unaccountably.

In short, our current moment is one of questioning the role of business as a powerful actor in the daily lives of Americans. This moment perhaps requires additional policy, appropriate to our time and current technology, to address. But furor over “big tech” and open or obvious censorship can mask subtler ways that non-government actors can make us less free.

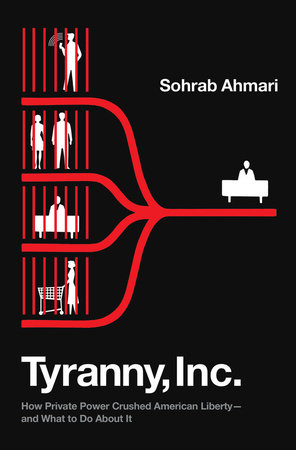

This, at least, is the argument of journalist Sohrab Ahmari in his new book Tyranny, Inc.: How Private Power Crushed American Liberty and What to Do About It. While battles over censorship on social media may be flashy and draw the most immediate attention, Ahmari’s book digs into the more mundane exercises of power by corporations against the political and financial interests of the “customers,” or the common consumer-citizen. Without realizing it, Ahmari argues, United States citizens have been trapped in a dense web of corporate control over their employment and occupation, emergency services, and even the mechanisms of justice available to them. The result is that while some citizens and policymakers alike are debating the appropriate scope of government intervention for fear of tyranny originating with the state, corporate tyranny grows in many sectors without obvious or immediate remedies.

Take, for example, my ostensible freedom to choose my employment, to voluntarily take on a contract with a potential employer, to negotiate fair wages, and to take my skills elsewhere if the contract becomes unworkable. In the ideal world of those Ahmari calls “market utopians,” a potential employer and employee enter this negotiation as equals, one requiring the services of the employee, one requiring the wages offered by the employer. Mutual interests motivate a mutual agreement, fair to both parties. This situation is disrupted, the market utopian might argue, when the government interferes with that free contracting process. Adam Smith, for example, argued that government was unduly interfering with the freedom of both employee and employer to submit their skills and needs to the judgment of others when, e.g., they enforce strict licensure requirements and artificially restrict the number of people who can occupy a profession, and the Smithian sentiment has carried forward.

But, Ahmari argues, our sensitivity to government interference in this arrangement obscures another source of power over the worker that even Adam Smith was aware of: the outsized influence an employer has over the potential employee in these negotiations. Rather than entering these employment negotiations as free equals, Smith and Ahmari both argue, the simple fact is that the worker needs to eat, while the employer can get along just fine without this particular employee at this particular time. This necessarily leads to an imbalance between employer and employee, especially when workers are discouraged (legally or otherwise) from “combining” to counteract that power in collective bargaining.

This imbalance leads, Ahmari argues, to downstream consequences: restrictive employment contracts that constrain behavior both during and after employment. Not only do these contracts restrict employees from seeking aid when companies mistreat them, they potentially prevent former employees from even mentioning that they left their place of employment, or why or under what circumstances they left. In this situation, not only is a former employee bereft of a paycheck, but they are also quite possibly hamstrung in looking for new employment if the circumstances that led to their departure were less than favorable to them. The “freedom to walk away” from at-will employment seems, in many cases, to be the “freedom” to launch yourself into the unsteady winds of “joblessness and financial misery,” particularly if your employment contract requires resolution of disputes through expensive and time-intensive arbitration that favors the employer.

The problem is not limited to employment contracts, however. Corporate tyranny can potentially expand to ensnare unwitting victims. Take, for example, private emergency services. Ahmari mines the news for several shocking anecdotes of people saddled with unexpected bills for ineffective private fire and emergency services showing up unrequested. Take, too, the steady elimination of local news outlets, victims of cost reduction after being bought up by national news conglomerates. The number of victims of emergency bills at the hands of private enterprise or those suffering from a dearth of local news essential to effective political participation are incalculable.

One of the most obviously distressing expressions of corporate tyranny, and the one that Ahmari appropriately uses to end the first, descriptive portion of the book, is seen in the legal ability of corporations to deftly avoid liability for crimes. Ahmari explains nuances of bankruptcy law that have been exploited by powerful corporations in the past to shield their assets from lawsuits resulting from their negligent behavior, even when wrongdoing was obvious and demonstrable. This results in victims of, e.g., medication side effects, coming up short in compensation when the corporation they are suing is suddenly “broke” and unable to pay damages due to legal and financial tomfoolery.

Cumulatively, the first part of the book serves to paint a distressing picture: workers are relatively powerless in many situations to advocate for themselves against corporations with outsized power. Even in cases where the law is on the side of the worker, corporations have resources available to avoid justly compensating those harmed by their reckless greed, while simultaneously gutting the resources and institutions that serve as bulwarks against this kind of encroachment.

If this were the entire story, Ahmari’s book would be a bleak one, and mostly serve to discourage. However, the second portion of the book is devoted to exploring an alternative path, “Another Way.” Our situation, Ahmari argues, was never inevitable, and need not continue. Speaking of corporations that buy up struggling businesses to loot them of their value and leave destruction in their wake, for example, Ahmari argues that “None of what” these corporations “do is ‘natural.’ None of it follows straightforwardly from the ideals enshrined in the Constitution. Rather, by promoting certain financial policies, or simply not promoting any policy—itself a form of state action—our laws have empowered Big Finance to loot the real economy.” In other words, where these corporations exercise tyranny over the individual, over local communities, and what Ahmari calls the “real economy,” they are permitted to do so by policy. This is, in short, a political issue, and the political solutions to our current situation take up the majority of the final portion of Ahmari’s book.

The “market utopians” and “harder-left socialists” that Ahmari criticizes often share a rosy belief that their preferred economic policies are truly beneficial. Few, it seems, are ruthless cynics, heartless tyrants, or monocle-wearing capitalists who desire the worst for their fellowmen. At the risk of alienating both of these groups, Ahmari outlines a path to the restoration of “political exchange capitalism,” a vision of a market moderated by political actors with a goal of preventing “unchecked private coercion” which “makes a mockery of equality and self-determination.” It affirms that “democracy and capitalism, politics and economics, must be brought in some measure of coherence, through the prudent regulation of market forces.” This, it seems to me, is an admirable goal.

Achieving that goal, for Ahmari, requires steps to restore the power of the worker in a system that too often favors the power of the corporate tyrant. That restoration in turn requires overcoming a latent hesitance among those on the American right, the small-government, libertarian sort especially, that seems allergic to class-sensitive analysis for its alleged Marxism. Against this, the tradition of “Western political theory stretching from Plato’s republic to even Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations,” Ahmari argues, affirms that power differences and growing resentment between haves and have-nots is a real, live, political issue with which we must grapple in forming our policy. In this, Ahmari is certain to alienate some readers in his treatment of Hayek and his followers, whose favored hands-off policies, on Ahmari’s account, contribute to the very tyranny they both decry.

Though squarely positioned in the American right wing, Ahmari offers a critique of corporate tyranny that ought to be persuasive or at least challenging to those far outside his standard political network. Indeed, the blurbs of Ahmari’s book anticipate this: figures as diverse as Slavoj Žižek, Fredrik deBoer, Josh Hawley, and Glenn Greenwald have expressed positive sentiments on his thesis. It is difficult to imagine many other books on which figures across that range might find some common ground. Tyranny, Inc. will thus likely serve as a touchstone of the conversation surrounding big business and the future of liberty, with which future commentators must grapple to contribute seriously to the subject.

In emphasizing that tyrannical behavior can originate from private actors, Ahmari is in good company. Alexis de Tocqueville famously reflected on the possible development of what he termed an “industrial aristocracy” in America, one characterized by the sharp division between laborers and masters, and one that threatened the preservation of both equality and liberty in America if left unchecked. Ahmari aids in restoring this broader understanding of potential and current threats to our liberty, and our political conversation will be the better for it.

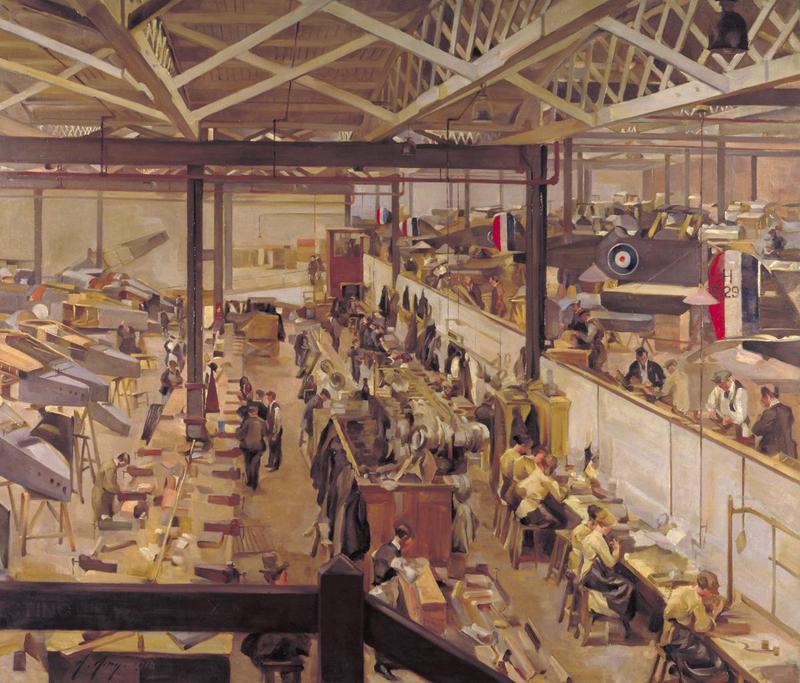

Image credit: “An Aircraft Assembly Shop” via Wikimedia Commons

2 comments

David Naas

I have never understood why Big Government is automatically bad and Big Business is automatically good, in recent Conservative theory. Nor why the same theorists celebrate the Entrepreneurial Capitalist while failing to observe most big businesses are Corporations.

If a Government bureaucrat is a baddie, does he become a goodie when employed by a Corporation. Considering the reciprocal movement between Corporations and Government, (from Legislator to Lobbyist and back again, for ex.) how are they different?

Whether Distributism is feasible absent a very powerful State to enforce it is another very good question, for another time.

Recall the Deep Space Nine episode, “Bar Association”? Even the hyper capitalist Ferengi society needs powerful government intervention to maintain it’s “free-enterprise” ways.

Just random thoughts.

Brian

It’s hard to imagine that the guy who was editor of the NY Post in 2020, whose communication ability was crushed by social media/government collusion in overt attempts to influence an election, could actually still think that “the problem” we currently face is private industry-based tyranny. Literally every example mentioned here of corporate abuse is one where they’ve worked completely hand-in-glove with government to shape legislation and regulations in their favor. The notion that “the answer” might therefore be policy based seems like delusional Pollyanna thinking.

“That restoration in turn requires overcoming a latent hesitance among those on the American right, the small-government, libertarian sort especially, that seems allergic to class-sensitive analysis for its alleged Marxism”

Was this written in 2015? Have you read anything outside of National Review in the past 8 years? Why in 2023 is anyone talking as if the “debates” between folks like Ahmari and the likes of French, Brooks, etc., have anything to do with actual energy on “the American right”, when in the real world Trump is steamrolling the GOP again and some random guy from West Virginia quoting hellfire psalms and singing songs about how insanely corrupt politicians are is a massive sensation?

Comments are closed.