Black Mountain, NC. The liberal arts seem like a lost cause. We live in a modern world. Our goal is to be successful, to pursue a life where one’s value is rooted in a job and output and paycheck. Just this week, I heard someone wax eloquently about homeschooling his child, because “much of what they learn in school isn’t practical.” Poetry and history—when did that lead to getting paid? Leisure and contemplation? Yuck. Sounds lazy. Get to work.

By and large, I think we’ve lost the post-industrial, pragmatic generation—the oft-criticized “boomers.” I don’t know if any parent of an emerging college student will read about the liberal arts. They want a cost analysis, a return on investment, a scalable product, a self-help therapy.

By and large, we are a culture who has little regard for the life of the soul.

I am a product of such a culture. I was not raised with an appreciation for the liberal arts. I could not tell you what they were, much less why to pursue such an education. From elementary school, it was ingrained in me to be practical. I don’t think any one ever said it so bluntly, but the humanities seemed a bit childish, the imagination too elementary. “When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child,” to quote the apostle Paul. “When I became a man, I gave up childish ways.” Whether spoken or not, an education was for growing up, and growing up meant being scientific and specialized.

The liberal arts were not a discussion in my college decision-making process. When I arrived, liberal arts classes were, at best, necessary burdens to get out of the way before starting the classes I wanted to take. Perhaps people defended the liberal arts to me, and I was too dense to hear, but I truly cannot remember anyone ever setting out a vision for the liberal arts. And so, like a good pragmatist, I took practical classes. I wanted to go into ministry, so every class had a ministry component. I took a science course, but it was geology of the Holy Land. I took an English course, and it was the literature of a Christian thinker (to keep things consistent). I was growing up, being trained, getting knowledge. There was no wonder, only application.

Now teaching at a Christian liberal arts college, I have a few “shticks.” One of them is that liberal arts colleges are the second most important institutions to nurture, give to, and preserve. (I’m a local churchman first, and the liberal arts are liberating but not salvific). I’m all for “soul-winning,” but it seems to be that there is no more urgent and pressing need than for Christians to be to be “soul-nurturing,” and one of the greatest ways that we have done that in the history of the church is through the liberal arts. I tend to be fairly pessimistic in convincing parents of students on the value of the liberal arts. However, we have our students’ ears walking into the classrooms of many of our institutions. And we can convince them of the value of the liberal arts. Having come of an age in a utilitarian and technocratic hellscape, our students know something is wrong. I am optimistic of convincing students and playing the long game.

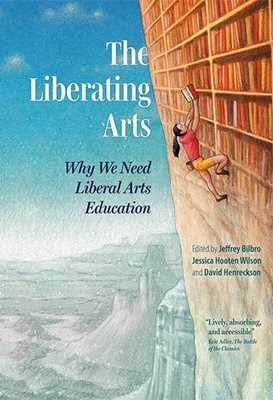

To help answer the important objections raised against the liberal arts, under the editorial direction of Jeffrey Bilbro, Jessica Hooten Wilson, and David Henreckson, the contributors of The Liberating Arts: Why We Need Liberal Arts Education render readers a great service. From a rich and diverse list of educators and practitioners, they come at the questions from different places, and what emerges from the cacophony of voices is a harmonious tune bellowing praise for the liberal arts. I can toast to that.

In outline, The Liberating Arts asks ten crucial questions: What are the liberating arts? Aren’t the liberal arts a waste of time? Aren’t the liberal arts elitist? Aren’t the liberal arts liberal? Aren’t the liberal arts racist? Aren’t the liberal arts outdated? Aren’t the liberal arts out of touch? Aren’t liberal arts degrees unmarketable? Aren’t the liberal arts a luxury? And, finally: Aren’t the liberal arts just for smart people? Unsurprisingly, the answer to the last nine questions is no. The liberal arts are not a waste of time, elitist, etc.

Each question also has three chapters with three different contributors. The answers are not exhaustive, but they are adequate and sandwiched between a practical example or exemplars of the answer. In other words, the middle chapter is the philosophical answer while the other chapters show rather than tell. To riff off St. Ambrose: God does not save by argument and reason but by lives. In his words: “But it was not by dialectic that it pleased God to save His people; for the kingdom of God consisteth in simplicity of faith, not in wordy contention.” These chapters serve as an invitation to taste and see how this is working in the world. In the words of the editors, the writers “intend to inspire by example and prompt readers to imagine analogous possibilities in their own lives” (4). A strength of the book is its short, quippy chapters, none of which are overburdened by explanations.

The concrete examples of the impact that the liberal arts make often occur outside the institutional structures of a college and university and displays what Chad Wellmon calls elsewhere (in both a pithy article and a worthwhile book) the “academy vs. university.” These practical chapters are rich examples of the liberal arts in practice that create generative ideas while stoking the imagination for how the liberal arts can play out in different contexts—whether with incarcerated adults or in elective adult education. To be honest, the liberal arts may work best outside the traditional institutional context, as costs of college continue to rise and the work of universities continues to fracture. I want to save the liberal arts college, but if the liberal arts prove to be most successful outside of the college frame, then let a thousand flowers bloom. As question three articulates, the liberal arts have been about common goods, not elitist goods.

One brief limitation: I am already convinced. And I imagine most readers who pick up this book will already be convinced on the importance of the liberal arts for “healing the deeper divides in our society by first healing our severed self” (Erin Shaw, 136) or teaching “us to love what is worth loving and to pass on that love to others in joy and friendship” (Jessica Hooten Wilson, 192). Sign me up! But of course, my name is already on the list.

We, of course, live in hope that those who are unconvinced may pick up and read and be convinced of the enduring value of a liberal arts education. I hope educators, administrators, and students hear the examples and are inspired toward a humanistic education, where questions are discussed, wonder is encouraged, and the life of the soul is nurtured. In due time, perhaps there will be a revival of the liberal arts. This book comes as valuable fodder for the burning wick of the liberal arts in our world.

Image Credit: Charles Courtney Curran, “An Alcove in the Art Students’ League” 1888 via Wikimedia