With all of the worries and whirlpools of existential angst in this world, declining readership of books is top of my list. Where does it rank on yours? Does it even make it into the top ten?

I was an active kid, outside fishing or hunting most days. And when I didn’t have a line in the water or a bead on a squirrel, I was riding my bicycle, a cool Spyder bike with a purple banana seat, all over town and usually the few miles to the local Carnegie library in downtown Lake Charles, Louisiana. That’s because most evenings I was perched on the couch at home reading until bedtime, and I needed an ample supply of books.

Even today, sitting quietly with an open book, slowly turning pages, one after the other, in measured rhythms, occasionally flipping back to reread a passage, is for me an escape pod from the current landscape of our world—not the natural world, with its own measured ways of experiencing, but the largely digital world by which it is now being supplanted. It strikes me that in escaping the modern distractions by reading a physical book, I plunge deeper into “real” life. Sadly, though, this appears to be an increasingly uncommon experience.

The data on readership is dire for those who value books in a culture, especially the numbers for young boys on their bikes. More than half of adults in the U.S. did not read a book to its end in the past year, and an astonishing 10 percent have not read a book in more than ten years. (This number may be lower than others you’ve seen, but that is because most surveys count as “reading” both listening to audiobooks—which, no matter how enjoyable that might be, is most certainly not—and skimming a few pages of a book but not finishing it.) Accounting for this depressing trend by age, readership falls off the map by the time we get to Gen Z—making this essay akin to bemoaning the lack of horse-drawn carriages on the interstate system. Even for those of us still in the category of readers, the number of books read annually is plummeting. And this is before we even consider the question of what is getting read.

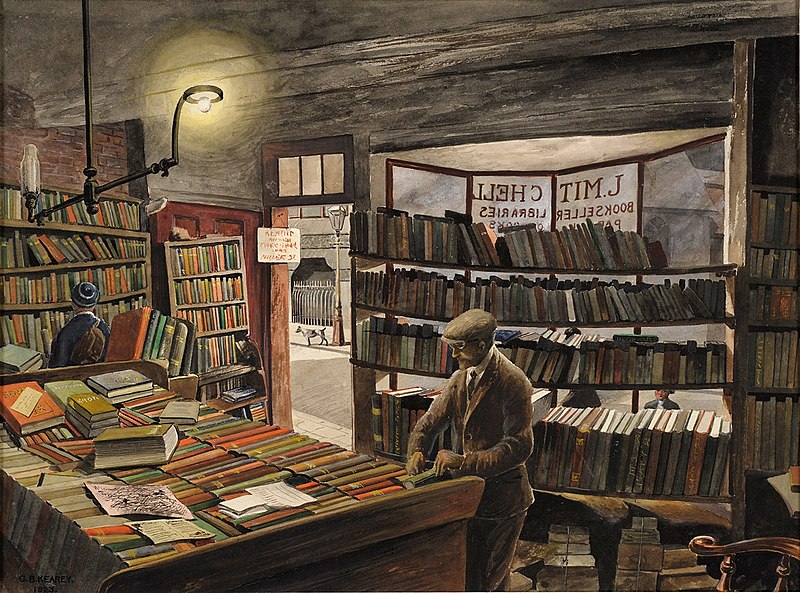

In the city nearest where I live, Knoxville, Tennessee, during the 1990s, these bookstores were in operation: Book Star; Barnes & Noble; Borders, two locations; Davis-Kidd, two locations; Apple Tree; Incurable Collector; Book Eddy; Printer’s Mark; Gateway; Walden’s, three locations; B. Dalton; Andover Square; a nicely curated bookstore that focused on rare Civil War finds; and a lovely by-appointment shop in a basement devoted to books on books. Also on offer: Books-a-Million, National Book Warehouse, Book Warehouse in four locations, half a dozen Christian bookstores, another half-dozen paperback exchanges, and McKay’s. That’s thirty-seven just off the top of my head, and I’ve probably missed a few. We’ll call it forty bookstores for an MSA population of 500,000. (I knew this world intimately, by the way, having worked in six of them and owned the Printer’s Mark.)

The book retail landscape has altered dramatically since those distant days. Today Knoxville supports Barnes & Noble (one location), McKay’s, Book Eddy, Union Ave, and a couple of pop-ups, paperback exchanges, and Christian tchotchke shops masquerading as bookstores. So let’s be charitable and say there are ten bookstores serving a metropolitan area population that is now about 750,000. What has changed in these intervening years? Amazon? E-books and audibles? Personal computers and smart phones? Reading habits? The answer includes a bit of all six and at least a handful more.

For purely selfish reasons, the declining health of the culture of the book sorely troubles me: my first book was released in October. And it has lots of company. An astonishing 500,000 to a million new books are released by publishing houses in this country each year, the number burgeoning to as high as four million when self-published books are factored in. Amazon alone lists thirty-two million books for purchase, a glacial moraine of print. All of this, of course, became of special interest to me when my own little book joined that mass of titles in search of readers, and ever since I have ruminated on this decline of a once vibrant culture that, despite the flood of new works, threatens the contemporary printed word.

These grim numbers suggest at least two questions: Who reads any of those new books? And, do we need up to four million new titles entering the market each year? The answer to the latter is “probably not.” I can’t speak for others, but I seem to mine the past for my book readings, much more so than any present offerings. (Do not let that admission, dear reader, prevent you from purchasing the on again, off again No. 1–selling new book release on kayaking.) Why then do so many books continue to be printed? Perhaps the phenomenon can be chalked up to residual human creativity—the ghostly light from a vanishing tradition and culture, the creaking machinery of commerce that continues to operate even after the mechanics who serviced it have long since died. That could help explain why readership surveys also show that while some Americans still buy books, more and more they just don’t read them. The publishing industry is like a mining operation on autopilot that follows a thinning vein of minerals: still over-investing even as the resource and the returns have petered out.

The dwindling number of bookstores and the apparent accompanying loss of interest in patronizing them is complicated. Yet it seems only fair to point out that our unwillingness to interact with others was a trend that had already been accelerating way before the pandemic kicked it into overdrive (Bowling Alone anyone?). It’s probably not an irony and should not be a surprise that the activity of reading a book, which is after all best done in quiet solitude, is ultimately unable to sustain or justify a public presence.

As an author, I have been going through the process (thus far, a seemingly futile and certainly unsatisfying exercise) of assisting the publisher and sellers with the marketing of my book. It’s a process with which, while I am no expert, I do have some experience. I’ve been struck by how curiously antiquated the printed and bound “product” is to those who are charged with putting it before the public. I’ve also been struck by the number of people in the book-producing-and-selling business who are uninterested in their product. On the retail end, there was the manager of a bookstore who admitted, without embarrassment, that she doesn’t read books and never has. She might as well have been stamping passports for the lack of excitement and knowledge she exhibited as she went about putting books on the shelves.

If the publisher of my book is an example, working in that industry has now become akin to selling harnesses to Model T owners. That could explain why the staff I’m dealing with have been genuinely at a loss as to how to actually promote books, one of the industry’s raisons d’etre. It also might help me understand why the “marketing specialists” would recommend that I post tweets, TikToks videos, and clever Facebook memes in a feeble attempt to pry attention from the distracted gaze of glazed-over eyes; why those marketing specialists had obviously never bothered to examine the titles they were tasked with trying to promote, yet offered pdfs informing authors up front why their book was sure not to sell–then, by their own lack of interest and skill, did their dead-level best to make sure those warnings came to fruition.

As for the traditional venues for using other print media to market new book titles? Well, they just don’t have the presence in our lives anymore to matter. Newspaper readership has dropped from a peak of sixty million in the 1970s to around twenty million today, and that number continues to fall. That a newspaper would decline to run a review of a book for an audience that no longer shows up to read even seventh-grade-level content is somewhat understandable.

As we move towards the possible civic apocalypse of 2024, I’m reminded of what reading books adds to our democracy. Although I often read popular fiction for escape, I just as frequently pick up a book of history or essays to educate myself in the art of being a better person or citizen. It is with that latter point in mind that I ask you to consider these scenarios: Would a Robert Kennedy, speaking to a black working-class crowd today after the assassination of a Martin Luther King Jr., quote Aeschylus … to nodding approval and understanding? In a presidential debate in the first half of the twentieth century, would a “journalist” have asked the candidates, “Which one of you onstage tonight should be voted off the island?” The former occurred in 1968, the latter in the past few months. You may draw your own conclusions about the current state of our informed citizenry and our aspiring leaders.

In all honesty, I don’t know how we can pass along the love and power of reading a book without the physical structures (which includes libraries that are more than just a venue to use free computers) that place them before our eyes. Books have always been a peculiar product, straddling the line between commerce and culture, encouraging personal dialogue and public discourse, both entertaining and enlightening. But in this, our present, more often than not, the physical book is just a dusty curio displayed in a museum no longer visited and seldom open for visitors. Reading a book is now relegated to the same exhibition hall world of playing bluegrass. What was once a front porch activity engaged in as family and neighbors has been relegated to obscure festivals, appreciated only by performing professionals and dwindling numbers of aficionados.

Having worked in the book business for three decades, I’ve watched the declining number of buyers and readers up close and personal, and the one trend that troubles me most is the vanishing boy from that world, the boy destined to become tomorrow’s citizen or even president: he has become a rare sight in bookstores and libraries, almost as rare as a bicycle with a banana seat.

…………………………………………………………………………….

Much of the research that I drew on for this musing comes from a study done by wordsrated. Although there have also been a host of studies done by other organizations, the picture painted is always depressingly similar. Also, if any of you discerning readers interprets criticism of a publisher to be aimed at Front Porch Republic, please note that my book’s imprint is FPR, which is substantially different than its publisher, which does the printing and promoting.

Image credit: via Wikimedia Commons

16 comments

Andrea Ostrov Letania

Why would you kill an innocent squirrel?

Moshe Goldstein

In the South I understand many people still eat squirrels.

Brian D Miller

I would suggest not reading my series on eating squirrel confit.

Diana Bailey

I read the first essay and ordered your book. Thanks for the opportunity!

Brian D Miller

I like this kind of news, Diana. Hope you enjoy it!

Laurence Holden

If “More than half of adults in the U.S. did not read a book to its end in the past year, and an astonishing 10 percent have not read a book in more than ten years,” then nearly 129 million did finish a book last year. That’s a lot of readers! But your experience, Mr. Miller, is more telling about the downward trend in the kind of intelligence inculcated by book literacy. Thanks.

Dutch

Not to be pedantic, but I think this sentence:

“Yet it seems only fair to point out that our willingness to interact with others was a trend that had already been accelerating way before the pandemic kicked it into overdrive…”

.. has a logic problem and should probably read more along these lines:

“Yet it seems only fair to point out that our growing reluctance to interact with others was a trend that had already been accelerating way before the pandemic kicked it into overdrive…”

Rob G

or change the word ‘willingness’ in the original to ‘unwillingness.’

Dutch

yep, that would work too. I guess they don’t read comments or don’t make fixes after publication. If I were the author, I’d be nagging them about it.

Brian D Miller

Thanks, gentlemen. Alas, the holidays got in the way of responding. Then I enjoyed my annual cold/flu. Then the polar vortex kept us busy on the farm. Heavy sigh. Last minute edits always seem to undo the work done before. Hope you both are having a good new year.

Brian

Martin

A welcome, concise, and thought-provoking essay, Brian. I was impressed by this couplet: “I’ve been struck by how curiously antiquated the printed and bound “product” is to those who are charged with putting it before the public. I’ve also been struck by the number of people in the book-producing-and-selling business who are uninterested in their product.”

I first became aware of the first half not in regard to books but in regard to speeches, reports, and other short printed documents, the English of which I was tasked with correcting and polishing for a Japanese translation/convention company in Tokyo, nearly 40 years ago. I had previously worked as a typesetter in NYC and was frustrated that the Japanese always insisted that the printed material have justified text (flush on both left and right sides).

One day it dawned on me: the client didn’t really know English that well, so if he had confidence in the translated content based on his relationship with our company manager, they could both enjoy the “product” by holding it at arm’s length and admiring how neat and clean it looked on the page. The fact that flush left had already been proven by studies to be easier to read (except for ad text) made me think that reading the “product” didn’t have a high priority for them.

I suppose the next incident sort of bridged the two sentences in Brian’s couplet. A bit more than 20 years later, I wrote a review of Braj Kachru’s Asian Englishes for Asia Times online. The hardcover book had been published by Hong Kong University press, which ensured that all the pages were glossy white (presumably never fading), but they had misspelled the author’s own surname several times within his text! Apparently, the point of the “product” was to make it visually appealing and the accuracy of the content was “uninteresting” to the publisher.

Finally, about 4 years ago, I published my own novel as an e-book, after a dozen of the 50 or so agents I’d pitched over the years had said, “Interesting but I don’t know how to sell it.” I then had a few people suggest that I pay someone to create a catchy cover for online sales. But I had no hope that any of these creative souls would actually read a 108,000 word novel before devising a fitting cover for it. Their livelihood was literally based on people judging a book by its cover, so why would they have an attitude distinct from that?

Brian D Miller

That is a fascinating story, Martin.

Debra

I come here from Paul Kingsnorth.

Maybe 7 years ago, or so, while rereading “The Return of the Native”, I put Hardy’s book into context. When writing that book, Hardy, as an excellent English writer, was documenting the steam roller effects of the industrial revolution on 19th century rural England. In “The Native”, the star of the book is Egdon Heath, not any one person, and Egdon Heath is populated by many people who are not literate at all. They don’t need to be, because their lives don’t depend on reading books, or newspapers. And because they are not reading books, they see another world.

On Egdon Heath, the people who read books belong to… the “elite”. For close to 2,000 years, or maybe even more, the word “elite” has meant “literate”, the people who can read, and who were valuable to society precisely because they could read.

What Hardy was documenting was how this ancestral definition of “elite” was going down the tube, with dramatic consequences that have unfolded for us.

While I believe firmly in reading books, the generalization of literacy has attacked other ways of learning, and knowing, and this is… dramatic (not that I am the least little bit enthralled with the screens… not at all. They foster idolatry, in my opinion.).

On the American based (very important, that one..) multinational that has been flooding the world, if you look at the home page, you will see that EVERYTHING is a “product”. That… is major idolatry. When everything is a product, then nothing is worth anything anymore, because there is no longer “value”.

At the same time that the value of reading books has been going down, the number of… authors keeps going up. Everybody ? wants to be an author ? Is this because according to the ancestral ideas attached to books, an author is/was… AN AUTHORITY, maybe ? Somebody who is an authority is… somebody, and not just anybody.

Good luck with the book.

Aaron Weinacht

Enjoyed the essay, Brian. I’m originally from Haviland, KS, pop. 500 and falling, where I used to ride my bike–a frankenstein affair with the high handlebars–down to the libary, where Dolores Stevens would help me out with getting whatever interested me that day.

If you’re interested in further statistics on reading habits, I’ll shortly have some. Feel free to contact me.

Aaron

Maria

I’m a writer and read three to five articles or essays daily. While I don’t “read” that many books by your definition – most of the 100 books I read each year are audiobooks I listen to while running, gardening, cooking, commuting – I do consider myself quite literate. As a writer, I read my own sentences aloud to hear the musicality. As a listener, I stop to annotate what I hear. As a person trying to own fewer things and to mind my budget, I rely heavily on the library and keep only the books that I quote from or re-read frequently.

In short, I think “literacy” is complex and definitions should be expanded.

Hadden Turner

Great article Brian,

Here in the UK, we still have a culture of independent bookshops in most towns and cities (though sadly my home city of Chelmsford doesn’t), though they are struggling against the behemoth of the “Dreaded Company Named After a Rainforest”. It is my habit whenever I am in an independent store to buy at least one book – they need all the help they can get.

It is striking isn’t it how in an age when it is easer to read any book than ever before (next day delivery etc) that reading physical books has declined so much. Surely social media competing for the attention-space contributes much to this, as does the paralysis of choice that is on offer.

Perhaps, though, the fact that the ‘transaction cost’ of acquiring a book has declined means that the value/preciousness of reading has also declined. It took you time and physical effort to collect a book from a library as a boy. The motivation for acquiring the book existed, and once acquired, there was an incentive to read fully what had cost you relatively “much” to acquire. Such hard-won knowledge was precious and valuable (and likely to be retained). Contrast this with the information overload and tidal wave of easily accessible book content that we are faced with today and the incentive value of reading perhaps has declined massively.

Hadden

Chelmsford, UK

Comments are closed.