Neither of us grew up hunting. Ensconced in upper-middle-class suburbia, our experience in the outdoors consisted of the occasional camping trip and a mild interest in neighborhood squirrels. These days, we both still live in suburbia, but our interest in squirrels has grown exponentially.

Squirrel hunting is a big deal in East Texas, and we’ve both managed to convince our wives that “limb chickens” can be excellent table fare and that their procurement necessitates significant upgrades to our small-caliber rifles.

But we’ve encountered a problem. Not having grown up in the squirrel woods, we don’t hunt as a matter of course. It’s not something we do because we’ve always done it. As Christians, this naturally raises the question: is it good for Christians to hunt animals?

It is certainly allowable for Christians to eat meat and use animal products. While some argue for vegetarianism by pointing to our pre-Fall state in Eden or the example of Daniel and his friends, God in Genesis 9 gives to Noah and his children the animals for food. God himself clothes Adam and Eve with “tunics of skin” in Genesis 3, Levitical law allows for a wide range of animal consumption, and Act 11:7 expands that range of consumption as God commands Peter to “slay and eat.” Thanks in large part to this biblical witness, the Church has never issued broad prohibitions against eating meat.

Admittedly, hunters in the Bible are not always the most exemplary characters. While warriors like David doubtless engaged in the activity (even if only in defense of livestock), only Esau and Nimrod are described as hunters.

There are, however, exemplary hunters among the saints and historic church leaders. St. Hubert was a prolific hunter who was famously converted when a crucifix appeared between the horns of a stag. Naucratius, the lesser-known brother of Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa, took to hunting to pursue “reflection, charity, and self-discipline,” according to Stephen H. Webb’s excellent article in the collection, “God, Nimrod, and the World.” Naucratius hunted to feed the poor, and he saw the pursuit as a “suitable analogy for battling and overcoming his own sinful nature.”

It’s difficult to argue, given this biblical and ecclesiastical precedent, that hunting for food could be intrinsically wrong or sinful.

Modern-Day Hunters

One might argue, however, that modern-day Christians have no business pursuing and killing God’s creatures. After all, few residents of industrialized countries need to hunt in order to survive. There are exceptions, of course, but those exceptions are increasingly fewer and farther between. For the vast majority of individuals, even those living in rural communities, it is often cheaper, more convenient, and safer to purchase chicken thighs from Walmart than to pursue and kill wild game.

Indeed, those who refer to hunting as “sport hunting” are highlighting precisely this truth. Given the global infrastructure of the commercial food industry, hunting is nothing more than a hobby, or worse, they argue, a game.

This critique of hunting doesn’t stand up to scrutiny for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that we don’t measure hunting by the same standard that we measure other now-commercialized activities. We don’t call doing one’s laundry “sport-laundering” because we have laundromats or cooking one’s own food “sport-cooking” because we have restaurants. If hunters are motivated by some primal love of killing, as is often asserted, one might also say that the only motivation to make vegetable soup is the dark desire to chop things.

The ability to buy meat at Walmart, in other words, does not invalidate other means of meat procurement. If we eat meat, someone must first kill an animal. Should it be us or the cattle processing center?

As the beneficiaries of modern food production, it’s easy for us to forget the constant presence of this choice. A professor of ours in college once asked our class of sophomores where food “comes from.” One student promptly responded, “The grocery store.” This professor, a Wendell Berry reader and owner of a hobby farm himself, turned visibly green (to our recollections) and shook his head in that depressed way characteristic of those tasked with shaping young minds.

Hunting, on the other hand, displays in visceral detail (literally) the death that must accompany meat-eating. Only those who purchase their food from a grocery store and have never visited a slaughterhouse could blithely dismiss hunting as a “sport” or a “game.”

For this reason, hunting may be even more essential for modern-day Christians than it was for prior generations. Technology has cut us off from death—both human and otherwise. We rarely glimpse the animals we consume before they appear before us, ex nihilo, wrapped in Styrofoam. Hunting can get us closer to a properly sober understanding of our Genesis 9 relationship to the animal world.

Hunting Makes Us Human

There is also, we would argue, a more profound benefit hunting can offer the Christian: to participate more fully in the preparation of food allows us to engage with the natural world in a more human way.

Humans don’t merely consume food—humans prepare food. And not for survival only, but for enjoyment and communal and cultic enrichment. It is ultimately more human to harvest one’s own meant than to rely on millionaires with cattle processing centers that can slaughter and package 100,000 cows a day. It is more human to grow and chop one’s own carrots than it is to eat microwave dinners.

To ritualize and honor these activities at once brings us closer to God’s creation and to the other humans in our communities.

We’ve recently started the annual tradition (three years going strong!) of holding a wild game dinner with our friends and church community. Each family brings a dish harvested from the East Texas area, and past menus have included crab, venison, wild pig, crappie, and, of course, squirrel. We tell stories about the harvest of each, and each family explains how the dish was prepared—from start to finish.

How would this experience have been different had we made food with meat from a store? We would have still enjoyed one another’s company, but we would have lost a clear sense of the sacrifice of the animals we consumed, the deep knowledge of the local fauna, and the relationships that develop among those who have struggled to overcome the obstacles the natural world presents.

The Christian understands, furthermore, that this human activity throws into stark relief our role as bearers of the Imago Dei. In his book, The Hungry Soul, philosopher Leon R. Kass argues that certain culinary customs, including meat-eating, distinguish “the place of man within the whole.”

“To mark his self-conscious separation from the animals, man undertakes to eat them,” Kass says. This is the post-flood “new world order,” and hunting and eating remind the Christian of the distinctions and boundaries God has ordained between humans and the rest of the animal world.

In Genesis, when God becomes the first hunter to clothe Adam and Eve, Kass argues that this event is the “first stage of humanization,” for it was the “beginning of concerned self-consciousness, shame and vanity, modesty and love, and all higher human aspirations.”

This is not to say that killing animals for human use is an unmitigated good. All eating is a “threat to order, life, and form,” Kass says. Eating is a problematic activity, both for the vegetarian and the omnivore. Christ himself points out in John 12:24 that a seed of wheat must first “fall into the ground and die” before it can produce grain, suggesting again that all eating involves the circle of death that feeds our life.

But despite this truth, God did not prohibit the Israelites from eating meat. Instead, he built into the Levitical law ways to remind His people about the “problem of carnivorousness,” as Kass calls it. Dietary restrictions prohibiting certain animals and incorporating others provided “constant concrete and incarnate reminders of the created order and its principles and the dangers that life—and especially man—pose to its preservation.”

Hunting brings this problem into focus. While the Israelites were reminded daily about the sacrifice of animals, modern industrial society has done everything possible to eliminate those reminders. Hunting helps us both remember the sacrifice that feeds life, and in so doing, forces us to participate in the Imago Dei by making what Kass calls “distinctions.”

“Creation is the bringing of order out of chaos largely through acts of separation, division, distinction,” Kass points out. God made these distinctions when he created the animals in their own kinds, and the Levitical law imposed distinctions between clean and unclean animals. To choose this animal and not that both recalls the troubling nature of taking life and allows us to participate in a small act of creation.

Good hunters, it need hardly be said, constantly discriminate. Some animals are illegal to kill, whether because they’re too small, too large, the wrong species, or the wrong sex. Others are too far away to attempt to make an ethical shot, and still others are too young to produce enough meat to justify the harvest. All meat-eaters, whether Christian or not, must make a distinction between human and non-human, but hunters take this creative necessity to an even more granular level.

Hunting also teaches that the place of man within the whole is not at the top of the proverbial food chain. God gave humans dominion over the plants and animals, but as stewards rather than as masters. Hunting, paradoxically enough, reminds us that we are not God. Like the whitetail and the squirrel, we require the fruits of the ground to survive, and we will one day succumb to the very fate we inflict. It is difficult to target, kill, and eat other non-human animals without being reminded of this fact.

In our experience, few activities are more humbling than taking the life of another animal. We see our place within the whole of God’s creation, and we understand more fully that we control very little of our lives—or our deaths.

Hunting, in short, is human. It connects us with the world as God made it and the way of life and way of death that is being forgotten in our technological age, and it thereby offers us a clearer picture of our place as humans within God’s created order. Many activities do the same, but few are as powerful or rewarding as the hunt.

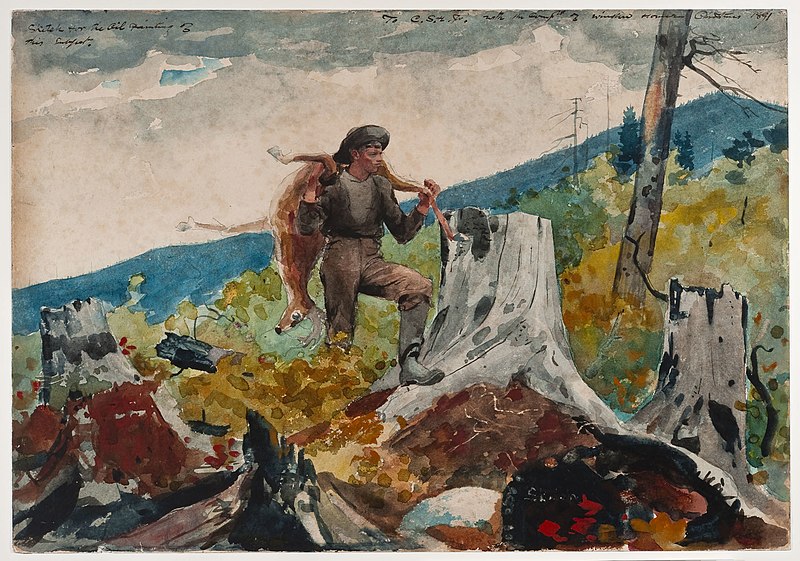

Image credit: “Guide Carrying a Deer” by Winslow Homer via Wikimedia Commons

Good piece. My brother and I grew up in “upper-middle-class suburbia.” There I remain, eating meat from the grocery store. My brother, meanwhile, moved to rural Idaho and hunts for a meaningful portion of his family’s food. I am keenly aware of the fact that his is the more ethical approach to eating.

The false belief that we are only morally implicated in the things we do ourselves and not the things done on our behalf would seem to go well beyond “buying meat at the grocery store vs. hunting.” For instance, we ask of our military things that many of us would have moral qualms about doing ourselves.

Just wanted to note that the Baylor-tied hunting-writing contingent of FPR carries on. Glad to see it.

Ok. Now you’re cooking. Check out the Texas based cookbook called “Afield”. Written by a big deal Austin chef hunting-convert. Everything from field forest flood to table and you will want to occupy every photo- even the field dressing/butchering views. His “Bad Day Dove Risotto” is a go-to for me.

I would argue that hunters, especially, should be involved in conservation and ecological restoration projects. They should work to restore habitat not just for game, but all species in their local ecosystems. Enjoy the hunt, guys, but give back to the land as well.

I think a good number of hunters would agree with you. There’s a really good section of one of the chapters from A Wing and a Prayer: The Race to Save Our Vanishing Birds where the authors discuss the role that waterfowl hunters and other hunting activists have made in helping save birds; the authors also argue that non-hunting activists can learn from these efforts and perhaps work together more closely in conversation together.

Y’all, I’m sorry but squirrels are tree rats. I’ll eat venison or wild hog all day long. but a rat is a rat even if you put it in dumplings (like my dad loved) or fried like mountian osyters or chicken gizzards with cream gravy (which my uncle loved) or roasted with yams like a possum (like my father-in-law loved)…

Wait a minute. Now I’m hungry. Curse you.

Comments are closed.