When the Williams family moved this summer from our long-time home in Carrollton, Georgia to Ashland, Ohio, a truth we had internalized for a long time became patently, weightily, painfully clear to our movers: our earthly possessions, all that we have stored up for the joy of moth and (book)worm but, most of all, for our own daily delight, consist largely of … books. A lot of them. Boxes upon boxes of them, which when unboxed in our new home, filled up a roomful lined with bookcases, and many more (bookcases) besides.

Indeed, the situation is quite dire, I’ve increasingly realized. Additional bookcases must yet be tucked in anywhere there is room to fit just one more. And so they fill every corner in the living room. A visitor ascending the winding staircase to the second floor will turn a corner to find a surprise bookcase greeting him or her at the top landing. I am wondering if I could squeeze a second one beside it and still leave sufficient room for the children to play chase in the upstairs hallway. Just outside the door to the book room (that aforementioned room that is packed to the proverbial gills with bookcases), there is another spill-over bookcase. Since the entrance to that room forms a sort of tiny alcove, it seemed like a good way to use it. So far so good, but I still have to find a place for maybe three or four more bookcases in this home to finish unboxing everything.

But, you might be thinking, we could just shove some book boxes into the garage for the time being and be done with it. Out-of-sight, out-of-mind is the quintessential modern American problem-solving strategy, and it sure does have a lot going for it, when it comes to dealing with our problem of stuff—that other quintessential modern American problem. Alas, it won’t work in this case, for we really do pull these things off the shelves regularly to look up one thing or another. And it is wonderfully convenient to be able to say “oh, yes, here’s where I read about this topic” to a friend who is over for dinner—and then pull the book I’m thinking about off the shelf, right then and there. Furthermore, in the meanwhile, the question regularly comes up: “have you seen such-and-such volume?” No, I regret to say, I haven’t. It’s still in a box, sorry. And (this last bit should be said in an ominous voice) Christmas is coming—and with it, more books. For what else would anyone possibly gift book-lovers? Blessings of this nature only keep growing in heaps—to be measured in more boxes or bookcases.

It all may sound rather extreme and chaotic, but the truth is that both Dan and I grew up like this—in families that were not wealthy, but that collected, hoarded, loved books like the wondrous treasure that they are. Indeed, this is a typical story for Russian immigrants, like my family—leaving everything else behind, the books we brought along. “A Motherland of Books,” Maria Bloshteyn beautifully dubbed this treasure trove of a library we all carried along. “Because who are you on a new continent, without books?” another immigrant and writer Sasha Vasilyuk poignantly remarked on Twitter, describing how her own mother lovingly packed and shipped their home library from Ukraine to California.

Now that we’re parents, we’re carrying on the family legacy and doing a mighty good job of conditioning our children accordingly. Their rooms too are packed with bookcases and their own books—well-loved and thumbed through regularly. At night, sometimes they ask to keep the light on for just a few more minutes to read in bed. A few minutes later, when I come back to turn off the light, I might find one of my younger book worms passed out asleep, mouth agape, a book still lovingly clutched in hand. I hope that dreams of skiing with Frog and Toad or picking blueberries with Sal follow.

Recent statistics about reading in America, however, suggest that this kind of experience is a rarity that is only becoming more unicorn-like. In a recent essay here at FPR Dixie Dillon Lane noted the discomfort that too many college students now exhibit with reading. The way they had originally learned to read did not condition them to be joyful and comfortable readers. And so, they complain even about having to muddle through twenty-five pages a week. Even more damning are the numbers that Brian Miller cited in his own jeremiad on this topic: “More than half of adults in the U.S. did not read a book to its end in the past year, and an astonishing 10 percent have not read a book in more than ten years.”

This is not a good trend—for one thing, as I noted recently, democracies need shared literature. And then there is the simple reality of our human nature: just like God in whose image we are made, we crave beauty and glory, and this includes the beauty of good literature. We feel the lack of such delights in our lives, even if we may struggle to articulate just what precisely we are missing.

But the problem that Lane and Miller point out is one that harkens back to childhood. Put simply, children who grow up in homes that are filled with books and a love of reading are likely to not be able to imagine another kind of life. Children who grow up in homes that do not delight in the written word, on the other hand, must discover such a love for themselves, on their own, perhaps later on. This is possible but is always harder to do. We replicate our upbringing subconsciously, good and bad alike.

And so, if you read this and wonder what you can do, start with examining your own home. Reading together as a family is a distinctly premodern joy—but a joy it most assuredly is. It is also a time of building together habits and memories that will last a lifetime.

When my husband was growing up, every evening the boys did dishes after dinner while the parents read aloud a book to them. Years later, the youngest of the four was back for Christmas break following his first semester of college. The first night back home, there he was in the familiar old kitchen, washing dishes after dinner when he asked, “so what are we reading?” Taken aback, the parents sheepishly pulled a book off the shelf and started reading, as though they had never stopped when this last child, now a grown man, had left home.

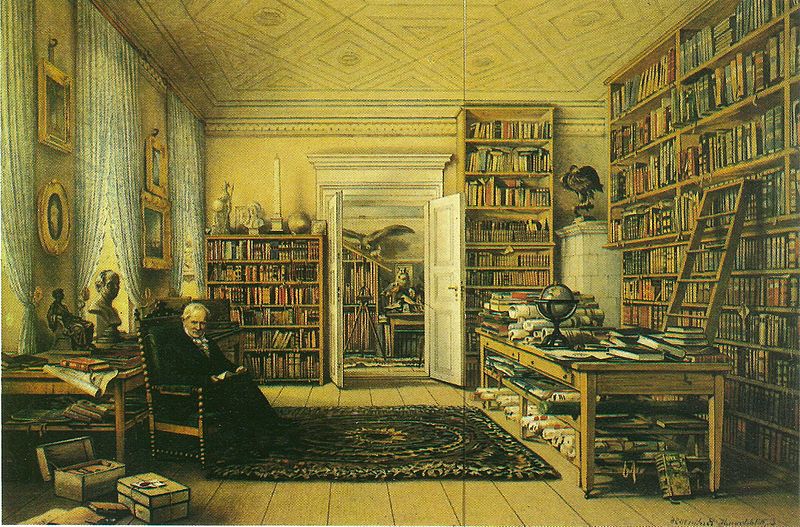

Image credit: via Wikimedia Commons

4 comments

Yelena

I was nodding my head throughout this essay, and the last paragaph made me tear up.

Grant

Nadya,

Thank you for this lovely article. It’s an inspiration to up my game reading aloud to my kids! (We used to live in Ashland, and have fond memories of it. We currently live in Wellington, 20 miles north of Ashland. I’d say it’s worth making the trip to look around town here sometime!)

Adam Smith

I think one of the most significant choices parents made was when they spent money they didn’t have to buy a set of encyclopedia britannicas from a traveling salesman (two things that don’t exist anymore). Not sure who I’d be if I hadn’t been the kid who was always browsing randomly through one of those red books. Thanks for this Nadya.

Aaron

You’ve described our family perfectly, Nadya. “hey, we could squeeze in some more books over here” is a sentence often uttered in my house. When we built a library, in a 12×12 room, I thought–silly me–that we’d have plenty of space. Wrong.

Comments are closed.