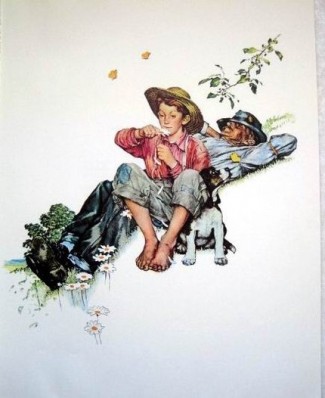

I am looking at another painting by Norman Rockwell, a part of his Four Seasons Calendar: Grandpa and Me in Summer. I know that I am not supposed to enjoy paintings by Rockwell, because the man had skill and humanity and wit and grace and love, just when the philosopher critics have commanded us to pretend to enjoy what is mock-primitive, bestial, flippant, awkward, and mean. But I enjoy Rockwell nonetheless, just as I prefer an easy conversation with a sane man to an argument with a lunatic. Norman Rockwell is sane.

In this picture, Grandpa is lying on his back on a green slope, with his hands behind his head for a pillow and his hat pulled halfway down over his eyes. It’s hard to tell whether he’s dozing or not. It seems that he’s in that blessed peace between a light nap and the calm refreshment of gazing up into the clear sky. A spray of scraggly birch leaves hangs over him from above. The boy, meanwhile, is lost in another kind of contemplation. He’s sitting in front, right next to Grandpa’s side. His straw hat is set back to reveal his whole face. The legs of his patched trousers are rolled almost up to his knees, which are tucked up, while his bare feet – big bony feet, scuffed and dirty with life, brace against the hillside. His she-dog beagle nestles under one of the knees, as she sniffs at one of the three yellow-paper butterflies flitting about. But the boy isn’t thinking of the dog or the butterflies, or even Grandpa. He has a wild daisy in his hand – there are a few of them on the slope – and he’s picking the petals off, one by one. “She loves me, she loves me not, she loves me,” that is evidently what is in his mind, as he looks at the flower, with the slightest trace of a smile on his lips, and his eyebrows raised just a little, in wonder.

Someone asks me, “What is our life on earth for?” I would answer, “It is for life in abundance, before the face of God.” But if he begged for a more proximate answer, it would be hard to do better than to point toward this picture, and say, “Everything on earth, all politics, all technology, all medicine, all economy, if they minded their business and got on with their work, exists so that an old man, a dog, and a boy can sit on a hillside, the old man dozing and looking to the heavens, the dog happy to be in the free air, and the boy plucking the petals of a flower as he thinks of the girl he likes best.”

I know that these are country people. Rockwell himself lived in the country during the summers when he was a boy, and living in the country meant work. That’s all right. The boy’s ankles and calves are those of somebody who has done a lot of chores – and a lot of running and climbing and walking. The old man is a wiry grizzled fellow, with wrists like leather straps. I’m not saying that all the mechanisms of civilized life exist so that people can have a vacation now and then. We desire not freedom from work, but freedom in and through our work, freedom for the large-hearted friendship and peace and wonder that Rockwell portrays in the painting. I go to an airport and I see people intent, stolid, jaw-locked, perfectly frozen in their busy-ness; but the old man gains more human good from his nap than they from their ergonomic tics. His treasure, if not in heaven, is in the sky, where taxmen cannot tax nor moths consume. I go to a university and see people clambering up the greased pole of ambition, to be noticed, to publish in the best journals, to win a scrap of astroturf from their departmental rivals. But the boy is more philosophical than they. They are in love with phantasms. He is in love with a pretty girl.

Now there are two ways to ensure that a scene like this is now inconceivable. One is to make sure that the boy and Grandpa never have the opportunity to relax on the hillside in the summer sun. The other, more reliable, is to make sure that there are no boy and Grandpa to begin with. In the end, though, perhaps the two ways are really one. It is to raise up a generation of people who cannot be free – who have grown so used to the four walls that do a prison make, that the open air, and silence, and the sky strike them with a vague terror. They prefer that the sky threaten, that they may have an excuse to get free of their freedom. They prefer the noise, lest they hear the still small voice that the prophet heard, who then hid his face in awe.

For it is true that the boy and Grandpa are free. It isn’t just that they are not straining their muscles. We could imagine that the boy were one of our contemporaries, sitting on the hillside, with a dull fidgety look, kicking at a rut. We could imagine Grandpa with his chin in his palm and his fingers over his nose and one eye, wondering why on earth his wife nagged him into taking a boring walk with a boring grandson on a boring day. And we could imagine the beagle, cocking her head with a half-whimper half-growl, as if to say, “What is wrong with you two? Can’t you smell the butterflies?” Freedom is the movement of the heart to embrace what is good, or beautiful, or noble. A man may be a servant, and admire; but a man who cannot admire is a slave. The world is given to us gratis – but will only be taken on those terms. We must be grateful to be free.

Then, if we don’t want the scene that Rockwell painted, we must raise a nation of slaves. Freedom, how do we hate thee? Let me count the ways.

The boy likes a pretty girl. That is natural. It is foolish to say that he is “bound” by his boyish nature to notice girls. It is like bemoaning the fact that birds are sentenced to fly. So we must instill in him what is not natural, to make a slave out of him. We have to clip his wings. We will tell him that girls are tramps, and show him some to prove the point. Or we will do worse than that. We will encourage him in the “freedom” of limping, or walking on his hands, or crawling, rather than in the normal sky-loving activity of a free boy, walking tall and straight, and noticing the astonishing strange thing in the world – a girl.

The boy is comfortable in his thoughts. That is natural, too. It is foolish to say that he is “bound” by his thoughts. It is like bemoaning that fish have water to swim in. So we must batter the walls of his sanctuary, to let other messages come in, those of our devising. Advertisements, sublingual songs, blaring headlines, unnatural colors, crying, “Buy me! Consume me! Take me! Now or never! Loser! Loser if you don’t! Buy! Look! Hey! Watch me!” It’s what school is for.

The boy is at home with the old man. That is natural, achingly so. It isn’t true that children like best to play with other children. They like best to play with old people, so long as the old people are children too. It’s as if the boy and the old man, in their matter-of-fact camaraderie, formed a fabulous beast indeed, one that would live to be three score and ten and three score and ten, with a pair of long legs and a pair of stubby legs, and a head addled by youth and a head addled by age, open to the wonder of just having come from eternity and to the wonder of being just about to return to it. It is not good for the old man to be alone, and that is why the Lord God fashioned him a grandson, poking him in the ribs and begging him to go for a walk into the everlasting hills. So we must keep them apart. If there is no generation gap, we must open one up, and make it as wide as a continent. For this purpose we sow something more destructive than differences. We sow indifferences.

Do we live in a just and sane society? How many old men and boys lying on a hillside have you seen?

4 comments

D.W. Sabin

Norman and a few confreres used to dress up as Injuns and descend upon Town Hall in Stockbridge to commemorate Thanksgiving and thats good enough for me. The man was a tremendous craftsmen and a fine observer of small time life during an era when Big City Lights and action painting held sway. God Bless Him. In short, he possessed skill and this skill depicted a forthright love of his fellow man.

Robert M. Peters

What I miss the most now at sixty-three are the years of being a child in rural Louisiana where feral hogs, wild cows, old dogs and boys ran free, the boys trying to capture for themselves the experiences that fathers, uncles, great uncles and grandpas had told of their youth while fishing, while sitting around a campfire, while bringing in a crop or neutering a bull. Although Modernity had already made its inroads in the post WWII period, there was still enough of the old ways and old freedoms of the commons in which a boy could apprehend the Greater Story told in the different and unique variations by the old folks. Through them, one knew that one’s own story was a part of that Greater Story. This is peace and freedom: to know that one’s own life has context and meaning in the Great Story and that somehow it is a part of that Great Story. They were and they remain a great cloud of witnesses: Daddy, Uncle Clyde, Uncle Aubry, Uncle Willie, Uncle Charlie, Uncle Luther, Uncle Doug, Uncle Kenneth, Great Grandpa Tarver, Great Grandpa Hawthorne, Great Aunt Perle, Great Aunt Mancy, Great Aunt Eva, Grandma Peters, Grandma Hawthorne, Uncle Julius, Uncle Frank, Mama, Aunt Bessie, Aunt Alice, Aunt Nell, even Uncle Bobby who was killed during WWII four years before I was born and witnesses to his nieces and nephews through the stories which his brothers, sister and mother told about him. There was Lester, Papa’s older brother by three years who died of appendicitis at the age of ten. Papa loved him and look up to him. Papa brought their brotherly antics alive at nearly every gathering. My father rarely spoke of the darkest things of WWII as a soldier, first in England and then at and after D-Day on the Continent. One dark moment contained a human element which transcended the darkness. During some fierce battle in France or Belgium, in one of those pulsating lulls, like a musical pause in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, my father came upon a young dying German soldier, gasping as the life fled from him. To Daddy, he looked like Lester. He paused, touched the young enemy as he died, and moved on trying himself to stay ahead of death. He was successful because I am here. There is a picture of Lester, healthy just months before he was to die, and my daddy, two tow-headed urchins, about ten and seven. Today, when I look at that picture, I see Lester and Daddy, the boys; and then I see Daddy, a man, fearful, in both senses of the word, looking into the face of the dying German and seeing Lester. This are the things boys apprehend and embody in their own stories if they run with men, real men. Papa always said that the hunt was preparation for prayer. A boy and a man must have a nature of attentiveness -body, mind, and spirit – in order to apprehend what he might not sense with the eyes and the ears, be it a well-hidden squirrel or God on the approach.

The dog in the picture: Polly, Red, Rosie, Samantha the Catahoula Leopard, and Miss Lucy Lee – the Southern Red Wolf. The dog has been in the aforementioned guises my friend since I can remember – loyal and faithful, not unlike God whose name is “dog” spelled backward. I have always suspected a very subtle humor in the Almighty.

Kenneth Cote

An absolutely beautiful essay. It reminds me of my own summer days back in the early ’70s, growing up in a little seaside town. A lobstering family lived across the street from us. Bob and Trudy, husband and wife, were getting on in years, and their son John was in line to take over the business (which he did, and he runs it to this day). Trudy was a child-loving soul. I spent many afternoons on her front porch (no pun intended) as she fed me Oreos and read Curious George books to me in her gentle voice like a cat’s meow. Sometimes, when the tide was turning and her husband was due back from hauling pots, we sit on a a bench on the dock and wait for his arrival as we chatted about lobstering, the weather, or what have you. I was about seven, and I remember loving those times even then. Little did I know how precious they would be to me in a future world of haste and worry. Bob and Trudy are gone now, God bless them, but the tide still goes in and out in my mind.

Thank you, Professor, for your thoughts.

Brian

This is good stuff. Reminiscent of “An Apology for Idlers” by Stevenson, and “A Lazy, Idle Brook” by Van Dyke (who wrote whole volumes in this vein). As out of step with the times as the telegram, which just went the way of the dodo (hey, when I get rolling with the cliches there’s just no stopping me). But necessary all the same. Keep up the great work.

Comments are closed.