PHOENIX, ARIZONA. Today is opening day, and how sweet it is. But nine days from now comes the most annoying day on the Major League Baseball schedule, when the league will engage in the annual display of self-congratulatory, maudlin, and mostly false sentimentality that marks Jackie Robinson Day. Every player on every team will wear Jackie’s number 42, and we will be subjected to interminable clips of today’s players telling us how Jackie “changed the game,” how “he changed America,” and how they “wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for him.”

There’s some truth to all of this. And Jackie Robinson really was personally heroic, besides being a fantastic second baseman. But not only will Jackie’s influence be comically overstated, it is hard to take historical analysis seriously from players who likely couldn’t date the assassination of Malcolm X within a decade, and who surely don’t know a single thing about Jackie’s pre-National League days or the Negro Leagues from which he came. Nor is it possible to take seriously the pious moral intonations of a league whose motives are so transparently self-serving. Yes sir, ring up the points for racial enlightenment and diversity celebration on April 15! (And push those pesky steroid stories off the front pages for a few days.)

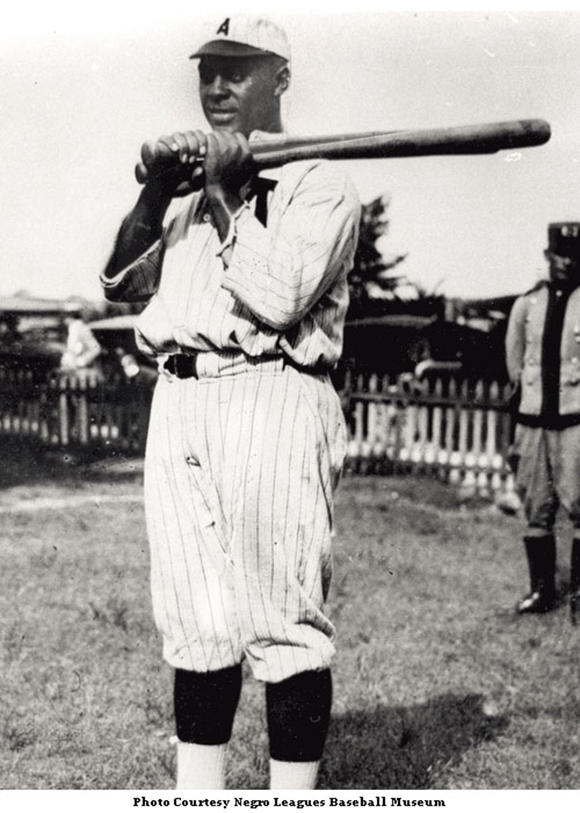

Aside from all the cant, though, one of the really unfortunate consequences of MLB’s single-minded focus on Robinson is that it pushes the other great black players of the pre-integration era — and at least a handful of them were not only better players than Robinson, but quite as good men — far into the recesses of the public consciousness. The effect is to prevent us from enjoying the personalities and talents of some of the best athletes America has ever produced. Satchel Paige is the only one of these players to be nearly a household name. Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, Turkey Stearns, and Cool Papa Bell? Much less so. And perhaps the most obscure of the Negro League greats was arguably the best player of them all: Oscar Charleston-the Hoosier Comet.

I have been a reasonably avid baseball fan since my father taught me how to read a box score when I was five, but I had never encountered Charleston until two springs ago, when I was whiling away a cold February night by flipping through the pages of Bill James’s (now there’s another hero) indispensable Historical Baseball Abstract. Here were James’s rankings of the top 100 players of all time. Charleston was ranked fourth. Fourth! And I had never heard of him. The first three names on James’s list were Ruth, Honus Wagner, Willie Mays. And five through ten (Cobb, Mantle, Ted Williams, Walter Johnson, Josh Gibson, Musial) weren’t exactly unknown. But except among the nerdy baseball-history set, Charleston seems to be utterly forgotten. Terribly unfair, says James (who it must be remembered is no friend to political correctness):

It’s not like one person saw Oscar Charleston play and said that he was the greatest player ever. Lots of people said he was the greatest player they ever saw. John McGraw, who knew something about baseball, reportedly said that. . . . His statistical record, such as it is, would not discourage you from believing that this was true. I don’t think I’m a soft touch or easily persuaded; I believe I’m fairly skeptical. I just don’t see any reason not to believe that this man was as good as anybody who ever played the game. . . . I believe that if there were a poll of experts about the Negro Leagues, Oscar Charleston would be selected as the greatest player in the history of the leagues.

James collects some of the most reliable assessments of Charleston. Negro League first baseman Buck O’Neill, a man of sound judgment, said that Charleston was better than Willie Mays — and that that made him the best player ever. “He was like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker rolled into one,” O’Neill told one inquirer. A veteran Cardinals scout said that Charleston was better than either Ruth or Cobb. Negro Leaguer Jimmy Crutchfield said that the only player who challenged Charleston for best-ever status was Josh Gibson. Similar high judgments about Charleston float around in various articles and memoirs and can be attributed to whites and blacks alike. He certainly left an impression.

If we can rely on eyewitness accounts, here’s what we know: Charleston was a lefty with blazing speed, power to all fields, fantastic outfield range (he played centerfield closer to the infield than anyone else ever had, and closer than perhaps anyone has since), and an arm every bit as good as the one that exists in Jay Cutler’s daydreams about himself (Charleston “had a stop sign on his chest” said one of the players who had learned not to test Oscar’s arm). He also hit for average, which made him the kind of five-tool player scouts fantasize about. Among our contemporaries, I would compare to him another five-tool lefty centerfielder: Ken Griffey Jr. But Charleston was definitely a better contact hitter than Griffey (with perhaps a touch less home run power), he had a better arm, and he was faster for longer. Plus, he was much more durable. (And Griffey’s no slouch: James ranks him as the seventh-best centerfielder of all time.)

Oscar Charleston (1896-1954) was born and raised in Indianapolis, where he honed his skills on the sandlots. Actually, he wasn’t “raised” there for long, because at the age of fifteen he lied his way into the army. He was stationed in the Philippines and starred for the 24th Infantry’s ball team. In 1915, he returned to Indy and joined the ABC’s, Indianapolis’s Negro League club. He spent his early productive years with the ABC’s but later — like many Negro League stars — he bounced around a bit, playing (and sometimes managing) for the Harrisburg Giants and for the legendary Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords teams of the early 1930s. That Crawfords team also included Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, and Satchel Paige. It easily could have given the great Yankees teams of that same era a run for their money (especially in a short series).

Charleston became a trusted advisor to Branch Rickey in the 1940s. Among other things, he allegedly recommended that Rickey sign Jackie Robinson. He returned to Indianapolis in 1954 to manage the post-integration Indianapolis Clowns. Shortly after the Clowns won their league championship, Charleston died when after a stroke he fell down a flight of stairs in Philadelphia.

I suspect that Charleston recommended Jackie Robinson to Rickey because he knew that Jackie had the kind of even-keeled personality that could thrive in the difficult, often humiliating circumstances he was bound to face. It was a personality that Charleston did not share. In short, Charleston was a bad-ass, the Eldridge Cleaver to Robinson’s Martin Luther King. He is remembered as a brawler, quick-tempered, ferocious, and intense. As a hot-headed teenager he knocked out an umpire when a fight broke out (OK, it didn’t just “break out”; Oscar helped to start it) in an ABC’s game versus a team of major leaguers (this altercation — and the fact that he fled the scene — earned him a little time in the Marion County Jail). He is said once to have ripped off the hood of a Klansman.

Not the kind of marketable temperament that the Major Leagues were looking for in a black man in the 1940s — or now. But Oscar was not a bad man. He was simply a supremely talented athlete who was sometimes controlled by his own compulsive competitiveness. Much like that later Hoosier hero — Bobby Knight.

Knight has been adequately lionized, and Jackie Robinson is the subject of dozens of books. But there is no biography of Charleston, and the facts of his life are difficult to disentangle from the legends. Some injustices take a long time to rectify, yet I’m willing to do my part. On April 15, I’ll tip my hat to number 42. But I’ll dedicate the day to the Hoosier Comet, the greatest player never to be assigned a major league number.

9 comments

Typical Whitey

Jeremy – thanks for a timely piece. I was an avid baseball fan for many years until the Strike. This story reminds one of the real sports heros and not the spoiled punks in professional sports today who have ruined the love of the game for many of us.

D.W. Sabin

What a great piece. For some reason, Charleston knockin out an umpire reminds me of Charles Mingus, the Great Stand-up Bass Jazz man driving around the bohemian era of Greenwich village in his convertible Caddie with a Dixie battleflag on the steering wheel. Mingus has also been branded as “too intense” but if you want to see the fruits of intensity in an act of joyful exuberance, listen to Youtubes recording of Mingus’s “Moanin” and tell me that don’t beat all.

In order to really celebrate things in this country they have to be congenial or obedient and I’ll never figure that one out given the fact that we were founded by a bunch of rabble rousers and need em frequently to set things right agin.

Here’s to the unacknowledged !

Bob Cheeks

Great piece, now can Mr. Kauffman regale us with a Muckdog story?

I once saw the Great One, Roberto Clemente play at the real Pittsburgh ballyard, Forbes Field, courtesy of the East Liverpool Evening Review. He made baseball an art form.

Josh Cooney

Typo: I meant, generally

Josh Cooney

Mr. Beer,

You are almost reviving my interest in baseball. I was quite the junkie as a youth and I do, in fact, remember reading about Oscar Charleston. I also had the pleasure of attending a Buck O’Neill storytelling session in Cooperstown. Negro League lore is an unknown treasure of Americana.

I would have to point out, too, that Jackie Robinson was known to be a bit of a bad-ass as well. I read his autobiography “I Never Had it Made” as an adolescent and, from what I remember, he would routinely get in fights with players and umpires, and shortstops were well advised who protected their shins around second base. Jackie was also a genreally conservative man, a Republican who campaigned for Nixon.

Comments are closed.