Two years ago I witnessed the abrupt transformation of an old and distinguished literary magazine. For the people doing the transforming, of course, the changes were long overdue. The overhaul continued the magazine’s proud history while renewing its ebbing prestige. For others, the makeover was more like a mugging—the destruction of something precious and rare. The fact that all of this took place within a few months—lightning-fast by print quarterly standards—made the episode all the more stunning. I knew immediately that I wanted to tell the story, but felt I wasn’t in a position to do so. I’d heard rumors about what happened, but I possessed few facts. Nor was I likely to find out more, for in addition to being in the dark about the new people in charge, I hadn’t really belonged to the old guard. I’d merely looked on, helpless and sad, as a corner of American letters was silenced.

After a while it occurred to me that I did know enough to tell a certain kind of story. The particulars, I realized, mattered less than the broader meaning of the tale. Perhaps I could offer (with apologies to Billy Budd) an “outside narrative” of a literary institution’s demise. It was the least I could do for a place I’d briefly called home.

***

Over the course of nine years I wrote sixteen essays and reviews for a magazine I’ll call the Bertram Review—or the Bert, as its friends might have dubbed it, if its name had in fact been the Bertram Review. I had heard of it since I was a freshman employed in the college library, putting the new issue on display in the periodicals room. The distinctive lettering on the cover signified elegant, old-fashioned splendor. Here, I thought with a touch of awe, was where serious poets and writers got published. Much later, nearing age fifty, with a newly rejected essay on my hands, I tried submitting to the Bertram Review for the first time. The editor responded with a dignified but warm acceptance, and I felt like a Victorian gentleman of letters being invited to join the Athenaeum Club.

A few years earlier I’d begun writing critical essays intended for the general reader, with no footnotes, technical terms, or extensive reference to other critics. It had taken me a while to learn this approach, following the example of critics like Edmund Wilson and Randall Jarrell. Just when I thought I might know what I was doing, I looked around and realized that hardly anyone was publishing such essays. When the Bertram Review accepted the next piece I offered them, I did something I’d never dreamed of doing with any other magazine that took my work. I subscribed.

Like most literary quarterlies, the Bert published a lot of fiction and poetry, occasionally dedicating the bulk of an issue to one or the other. Typically, however, the balance tilted toward nonfiction, to a much greater degree than you’d find in comparable publications. These essays ranged from memoir to biography to literary criticism, with an emphasis on books and authors that contrasted sharply with the “creative nonfiction” prevailing elsewhere. There was a good deal of literary reminiscence, some name-dropping, a bit of high-class gossip. The criticism treated any writer, period, topic, or work that the contributor happened to find interesting, and that Bert readers might find entertaining. Uniting this unpredictable array of essays was an unabashed love of books and reading, as well as a disregard for fashion, intellectual trends, critical jargon, or politics. I never saw an essay in the Bert about a comic book or a pop star, or even a movie—probably a function of the editor’s cheerfully cast-iron prejudices.

As my subscription quickly made clear to me, the Bertram Review was written almost entirely by regular contributors, of whom, apparently, I was now one, despite being only lightly published and two or three decades younger than most of my fellow writers. As the months and years went by I formed opinions about these contributors, like any subscriber to a magazine. There were writers whose work I admired and looked forward to reading, and others I routinely skipped. As a contributor myself, I naturally compared my work to theirs. One writer I frankly regarded as my rival, because she wrote criticism in a first-person autobiographical vein while I cultivated a mind-your-own-business third-person manner. My rival adored Dickens, and reread David Copperfield with reverent fervor, while I thought both were overrated, despite my fondness for Bleak House and Pickwick Papers. When I slipped into one of my Bert essays a disparaging remark about David Copperfield, the dig was half aimed at my (probably oblivious) rival. The competition, if that’s the name for it, was good-natured and benign—a mutual sharpening of disparate abilities.

You wrote for the Bert because you loved literature, and because you counted on a hearing from like-minded readers.

Many Bert writers, I noticed, were university professors. Quite a few had written distinguished scholarly works. I assumed that they wrote for the Bertram Review as a kind of holiday from their professional activities, leaving specialists’ disputes, technical lingo, and citation procedures behind, and placing themselves in the hands of our eccentric chief, the editor. You wrote for the Bert because you loved literature, and because you counted on a hearing from like-minded readers. You did it because this quarterly promoted an endangered breed of essay, and because you got a charge out of seeing your work in its pages. Regular contributors often got to know each other personally. A few, I was told, rebuffed overtures from their fellow writers, but others sought each other out, with the editor’s glad assistance, and commenced long correspondences and friendships. Regardless of whether we knew each other, liked each other, or ever met in person, we communicated through the essays we wrote. In the judgments we made and the opinions we expressed, we carried on an implicit, between-the-lines exchange.

***

Of course I understood from the beginning that it couldn’t last. With its octogenarian writers and disdain for fashion, the Bert shuffled amiably toward its fate. I knew that somehow, most likely within a few years, the Zeitgeist would take revenge. I just didn’t think it would happen so brutally, and so quickly.

Word got out that the editor was retiring. A short time later his replacement was announced, with an absence of fanfare and a paucity of detail that bordered on the surreptitious. I remember having to Google the guy, and not feeling encouraged by what I found. Clearly this would be no seamless transfer of power, no handing down of a legacy to an anointed successor. Bert contributors speculated worriedly, and waited.

The final issue before the changeover contained an “homage” to the outgoing editor: thirty-three tributes by writers who’d sent him essays, fiction, and poetry for many more years than I’d been a contributor. The tributes were a roll call of names I knew as members of a unique community. I wonder now how many of them knew or guessed that they were bidding farewell to a magazine as well as a man.

Again we waited. The new editor’s debut issue arrived, featuring a different look on the cover—no small departure, for the magazine had been known for its stately, uniform design since before my days in the college library. On the first cover of the re-invented Bertram Review, the familiar old color and lettering were reduced to shards floating randomly against a new background hue. This transition would not be subtle or organic, the cover declared. They had blown up the Bertram Review. Inside, the old names were almost entirely gone. I’d already received my first and last rejection from the new editor, a terse email informing me that my work didn’t suit the needs, and so on. In one way or another my fellow contributors had learned that they too were no longer welcome. Whatever the Bertram Review would be from now on, it wouldn’t be the people who’d gathered four times a year to tell stories, argue, and wonder at the world.

***

At this point my story becomes even more an outsider’s, because I can’t describe in any detail what the magazine did become. I stopped reading it. A conscientious reporter would rectify this situation and read the handful of issues, but I felt like someone had burned down my house. Put another way, reading the rebooted Bertram Review would be like attending the wedding of an old flame who dumped me. Shortly after the new editor was announced, I’d renewed my subscription, wanting to be a good sport and hoping for the best; but as each issue arrived I skimmed the contents and threw it away.

So I don’t know exactly what the new Bert is like—but from the moment I laid eyes on that first exploded cover I had a good idea of what it wasn’t. I was also pretty sure I knew the kind of magazine the Bertram Review would become. It looked, from its refurbished cover to the predominance of fiction and poetry in its contents, like any of the countless magazines that support the Creative Writing Industry—magazines that help writers chalk up credentials so they can get jobs teaching other people how to write. I’d published a handful of essays, even one story, in such magazines. I never read them.

Why would anyone read one of these magazines rather than another? What would make anyone call it home?

What bothered me most was that the Bert was becoming one of these interchangeable magazines. You could bemoan the loss of common-sense, jargon-free criticism, or point to the ever-shrinking territory between popular culture and academic scholarship. The wreck of the Bert surely aggravated these woes. But worse, I saw the Bert being overwhelmed by a remorseless, featureless tide of professionalism. What had once been a joyful haven from professional demands was now, under the guise of a hipper, less starchy appearance, a means of beefing up CVs and getting jobs. Where once a particular community shared a love of literature, you had a place to shelve the shiny objects that got you tenure. Why would anyone read one of these magazines rather than another? What would make anyone call it home?

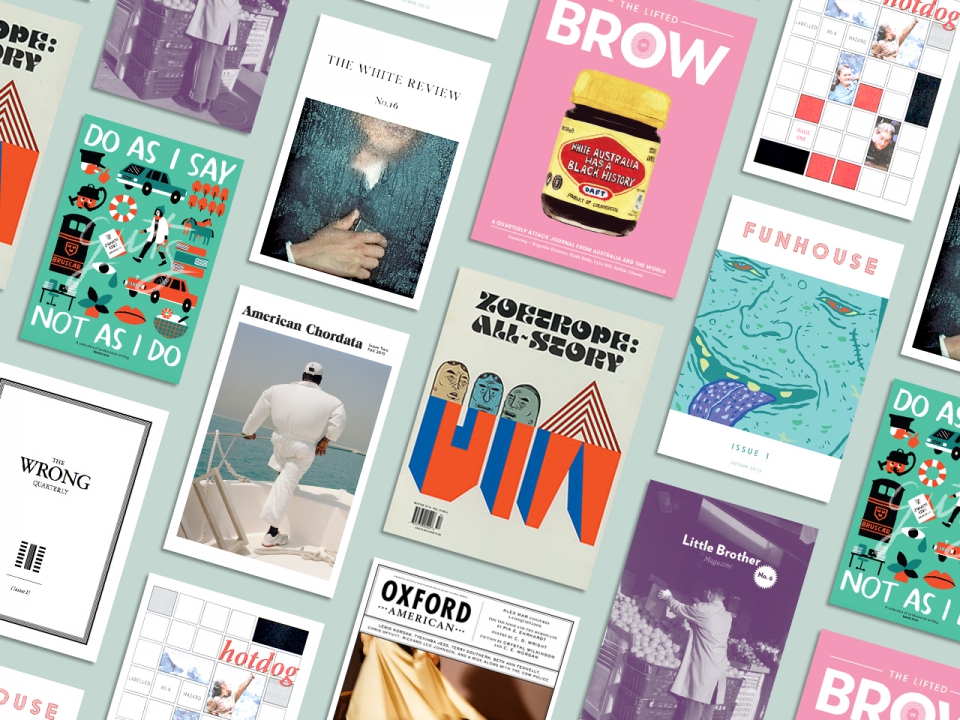

The intrigue and the political maneuvering that blew up the Bert left a few people bruised and angry, but the flattening of the literary landscape impoverishes everyone, just as the flattening of the actual landscape does. A swarm of beautiful magazines, with their sprinkling of big names and pleasant surprises, is still an attractive, undifferentiated swarm. Each quarterly boasts “the best” in contemporary literature, laying claim to some essential niche, but they all look the same—snazzy and up to date—like the signs that recur on any interstate, and like the food served up in any exit eatery.

In its heyday, the Bert was a slow-motion, gloriously tactile cousin of websites like FPR. What took place in print over months and years, among writers and readers sharing a certain temperament and a common pursuit, happens here in a matter of minutes and hours. At FPR, ideas, observations, and perspectives mingle, with participants ready to weigh in instantly on their companions’ offerings. But such communities, in print or online, don’t last forever. They succumb to pressures from within and without, or they simply outlive their purpose. So, Porchers, love that well which thou must leave ere long, and let’s hope it’s a good long ride.

10 comments

Dave Lull

The Critics who Made Us: Essays from Sewanee Review

https://books.google.com/books?id=brRD6-B5MswC&dq=9780826209160&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Revelation and Other Fiction from the Sewanee Review: A Centennial Anthology

https://books.google.com/books?id=RDqTAAAACAAJ&dq=9781564690203

A review of Revelation and Other Fiction can be found here:

http://www.unz.com/print/Chronicles-1993aug-00041/

“Quarterlies and the Future of Reading” by George Core can be found here:

https://www.vqronline.org/essay/quarterlies-and-future-reading

Dale Nelson

For those of us who failed to read the journal in question during its best years — are there books that collect pieces from those years, or, at least, that reflect the quality & subjects thereof?

Mel Livatino

A wonderful and true piece of writing by a very gifted writer. Every word was right and necessary, and all of it beautifully written. It also brought back the pain of losing the Sewanee Review. Actually, it made me feel just how irrevocable is the loss — far more than I had realized in these last two years. It made me feel that I have been through another loss in the family. The thing so many of us who have lost a dearly loved one feel most powerfully is that we’ll never hear that voice again, we’ll never see that smile again, we’ll never be touched by that hand again. Never! That’s where grief hits the marrow of the bone. I know nothing more painful than that. To a lesser degree, and for the first time, that’s what David made me feel as I read his piece. We lost a voice, a smile, a touch of the hand, a look, a glance of love when we lost the Sewanee Review. SR and The American Scholar, when it was edited by Joe Epstein, were the only two literary journals I longed to read the moment they came in my door. I was especially touched by pieces in every issue of SR. Since Adam Ross took over, all I see is the wish to be important and dazzling, neither of which has happened, or ever will. More than 120 years of distinction and greatness drowned in vanity in just a few months time. In the last two years I read only one piece that touched me. My subscription just lapsed. I won’t miss it at all.

Lucas Nossaman

Thanks so much for this piece, and I think your laying the blame on the Industry, actually, is spot on. I feel I should contribute a comment as a “younger” reader of SR. As a graduate student who daily hears about the need to stay within bounds of the triad, “race, class, gender,” SR was my go to for reading about ideas rather than mere trends. I started subscribing in 2011, and I am so glad I got to experience that brief time with the older style. I continue to subscribe (though the latest issue may be enough for me to pull the plug). I fail to see how SR has transformed into something more “tolerant,” other than to pursue the vague goal of “inclusiveness.” Indeed, thinking about all this from the perspective of the Industry makes total sense. I happen to sympathize with the need to include a variety of types of writers and subjects and to address race/class/gender more explicitly at times, but this, in the case of SR, has made them but another of the splashy journals beholden to Creative Writing.

Wendell Berry, I suspect, will receive the same rejection letters from now on. I will say that a few pieces have given me hope: Adam Kirsch on Christian Wiman, John Jeremiah Sullivan’s “Curses,” and Ryan Wilson’s poetry. But overall, very disappointing transition. I would like to hope that FPR could then fill a gap, but nothing beats a solid print quarterly to slow down the pace.

Jeffrey Bilbro

Lucas, you’ve outed yourself as failing to follow the most important rule when reading literary journals. As Jason writes, “Scholars read with both eyes wide open, one eye open toward publication and the other open toward publication—the point of a literary life being, obviously, publication.”

David Heddendorf

My thanks to everyone I’ve heard from, corroborating my take on what we all agree was–to borrow Jason’s characterization–a shameful turn of events.

Some of us seem to want to expose the perpetrators, others to bemoan the state of literary criticism, and still others to laud the badly mistreated former editor. I share all these impulses, but my main concern in writing my essay was to narrate a particular instance of a general trend. I think the real villain here is the Creative Writing Industry, without which the nasty business at “the Bert” probably wouldn’t have happened. It seemed to me that FPR was the ideal place to point this out, for reasons I explain toward the end of the essay–chiefly the supplanting of neighborly distinctiveness by impersonal uniformity. The fact that there’s some overlap between Porchers and friends of the old SR is clearly not a coincidence!

Jason Peters

A fine essay, elegant and sensible.

I like a good mystery as much as the next guy, but a part of me thinks a public shaming is in order. So: a little shameless self-promotion to pull the cover off (by permission of Mr. Heddendorf). My subscription got lost during SR’s transition from stateliness and respectability to deliquescence. I didn’t bother to renew it.

Rob G

I too know the journal in question, and had exactly the same feelings, and in fact had thought about writing a piece very much like this. I let my subscription lapse after I read the first two “new” issues. As you say, it was now one of those “interchangeable” journals, no different than scores of other modern literary quarterlies, alas. And as of yet I’ve found no replacement.

One bright spot: I had only been reading the journal for about five years when all this went down. Old issues are not too difficult to track down on the internet, so I’ve begun picking up the occasional older volume, recently coming across, for instance, an Allen Tate tribute issue from the late 50’s.

Brian

Sounds like a good analogy for lots of societal decay problems, where there is a whole community who enjoy something, but only a single person who drives it, who is the single-point failure for the whole enterprise.

I suggested to our small-town mayor that we should have a street festival downtown. He said we used to, and it was a big success, but one guy did all the work for it, and when he retired, no one else picked up the slack, and that was the end of that.

Is this magazine a bunch of paper with that name on the front, or is it the occasional collected product of that community of writers? If it’s the former, then it lives still. If it’s the latter, then why can’t someone else step forward and do the extra work to resurrect it, even if the name on the front has to change for legal purposes? If no one else will, then the magazine was clearly just the former editor’s product, not yours.

Christian Casper

I know the journal in question. It was my favorite before the editorial change. I agree that it felt like a mugging.

(Aside: I spent my undergraduate years happily in Ames, Iowa.)

Comments are closed.