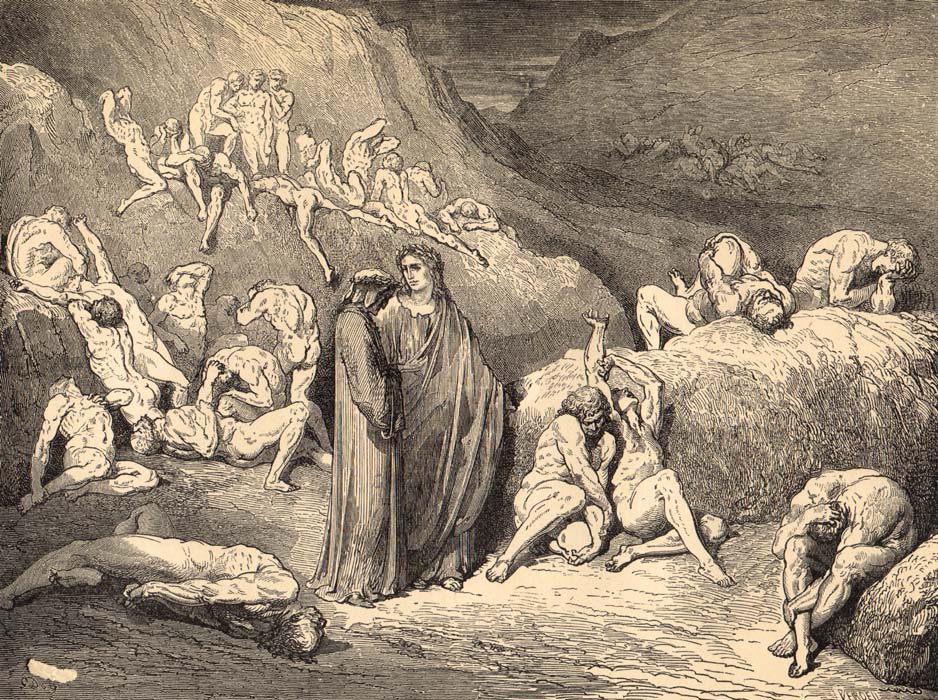

In Canto XXX of the Inferno, Dante becomes fascinated with an argument between Sinon the Greek and Master Adamo, both of them condemned for sowing discord. Virgil, his guide through hell, becomes angry at the pilgrim for his misdirected attention. Dante tells us that

I heard the note of anger in his voice

and turned to him; I was so full of shame

that it still haunts my memory today.Like one asleep who dreams himself in trouble

and in his dream he wishes he were dreaming,

longing for that which is, as if it were not,just so I found myself: unable to speak,

longing to beg for pardon and already

begging for pardon, not knowing that I did. (30.133-141)

This episode seems particularly relevant to the social media age, for a couple of reasons. First, there’s the rebuke itself and the events that lead up to it. Virgil is angry at Dante not for participating in this argument himself but for standing on the sidelines, as it were, and enjoying watching other people tear each other apart. It doesn’t take a great act of the imagination to apply the rebuke to those of us today who enjoy watching the train-wreck conversations that often accompany the comments sections of various online media outlets—for, as Dante well knew, there is an immense and indecent pleasure in watching other people, especially people whom we instinctively feel ourselves better than, hate one another.

In Dante’s world, if shame is repentance, confession is forgiveness.

Even more important is Dante’s response to his mentor’s rebuke. He “long[s] to beg for pardon and already / beg[s] for pardon, not knowing that I did.” The feeling of shame is a form of repentance, an ethic that Virgil himself affirms in his reply to Dante’s response: “Less shame than yours would wash away a fault / greater than yours has been [ . . . ] / and so forget about it, do not be sad” (30.142-144). In Dante’s world, if shame is repentance, confession is forgiveness. This message seems indispensable for our culture, in which people tend, on the one hand, to disclaim all cause for shame in their own behavior and, on the other, to dedicate themselves to online shaming of anyone who crosses the invisible line demarcating the bounds of social acceptability—generally not relenting even if the line-crosser confesses. Every few weeks provide us with new examples of crowd-shaming, and often, as in the recent Covington Catholic case, the mob descends without having the whole story, or caring much about it.

Much has been written, the last few years, about the culture of online shaming. Most notable is Jon Ronson’s book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, which relates the stories of a number of people who have been (often unfairly, always disproportionately) punished for their errors and sins online. The book accomplishes the impossible: It makes the reader feel sorry for the disgraced pop-neuroscience writer Jonah Lehrer. But it also demonstrates the degree that the stance that fuels online discourse is frequently semi-principled outrage. The Twittering class is spiritually nourished by righteous indignation:

After a while, it wasn’t just transgressions we were keenly watchful for. It was misspeakings. Fury at the terribleness of other people had started to consume us a lot. And the rage that swirled around seemed increasingly in disproportion to whatever stupid thing some celebrity had said. It felt different to satire or journalism or criticism. It felt like punishment. In fact, it felt weird and empty when there wasn’t anyone to be furious about. The days between shamings felt like days picking at fingernails, treading water. (89)

The culture of shaming thus poisons the souls of the shamers even as it destroys the lives of the shamed. We become driven by our desire to shame other people, even as we quietly fear that we will one day cross the invisible line that will call down the rage of the masses upon our own heads. And this is true even when the object of our rage more or less deserves it: Brock Turner, the Stanford athlete who raped a drunk woman behind a dumpster, should absolutely feel ashamed of himself. But when we attack him from behind a screen, we aren’t contributing to his shame, but rather to a culture in which everyone is a target. We bypass the proper channels for these things—partly, I must admit, because the legal system failed to deliver justice in this case—but in bypassing them we create a culture in which there is no due process. We are in effect reading Aeschylus’s Oresteia in reverse, moving from the judge and jury of the Eumenides back to the endless hall of mirrors of the Agamemnon, in which murder will follow murder indefinitely.

Online shaming allows us to feel virtuous without actually considering our own virtue; even worse, it allows us to feel virtuous while being vicious.

More than all this, public shaming is fundamentally easy for the people who propagate it. Once the dogpile has begun, there is little if any risk for the individual shamer: I can toss out 140 characters easily, feeding my sense of social justice and signaling to the people in my circle that I hold the correct moral and political opinions. (This is Joseph Bottum’s compelling argument in An Anxious Age: as American civic religion declines, it is replaced by a desire for public personal purity.) What’s more, I am removed from the personal consequences of my shaming. The people who attacked Justine Sacco in 2013 for a failed joke about racism didn’t have to worry about what would happen to her after she lost her job; to the degree they thought about it at all, many of them were glad to have effected such a change in the world. The irony is that their criticism of her involved her failure to feel empathy—the great sin of our therapeutic age—but few of them felt any genuine empathy for her. Online shaming allows us to feel virtuous without actually considering our own virtue; even worse, it allows us to feel virtuous while being vicious. It is fundamentally anti-reflective.

Given these dire conditions, it’s tempting to agree with Ronson that “The cure for shame is empathy” (283)—the master virtue of our age. In fact, Ronson seems to want to engender empathy and destroy shamings by eliminating most moral categories altogether. The problem with online shamings, he says, is that they create “a more conformist, conservative age” because when we engage in them, “We are defining the boundaries of normality by tearing apart the people outside of it” (281). The solution, then, must be to accept all people for the unique beings they are and to write off their moral failures by expanding our definition of “normalcy.”

Why Shame Matters

The problem is that this implicit conclusion is contradicted by Ronson’s own research. He talks about the public shamings perpetrated by the infamous Texas judge (and current Congressman) Ted Poe. He began investigating Poe assuming that he was a monster, different from Twitter shamers mostly in the amount of political power he held. But his interview with Mike Hubacek, a teenager who killed two people while driving drunk, pointed to the efficacy of Poe’s approach. Hubacek was forced to stand on the side of a highway wearing a placard reading “I KILLED TWO PEOPLE WHILE DRIVING DRUNK.” The punishment was humiliating but strangely redemptive. Hubacek remembered nothing of the fatal accident, and, in his own words, “almost convinced myself I was in a living purgatory. I lived to suffer. I went more than a year and a half without looking in a mirror” (87). His court-ordered punishment, however, alleviated his suffering: “There on the side of the road, he said, he understood that there was a use for him. He could basically become a living placard that warned people against driving drunk. And so nowadays he lectures in schools about the dangers. He owns a halfway house—Sober Living Houston. And he credits Judge Ted Poe for it all” (87). His public shaming—and the public confession it engendered—turned his life around—the polar opposite of Justine Sacco’s experience, or Jonah Goldberg’s. And expanding the definition of normalcy wouldn’t have helped Hubacek at all; it may even have harmed him if he came to think that drunk driving was no big deal. (Nor, it must be noted, would a jail sentence have done much better.)

Poe’s sentence, at least in this case, was an act of compassion, not of hatred or fascism. Shame served the purpose it was meant to serve: It pushed Hubacek not just to a recognition of his sin but to the fact that a world existed beyond it, that while the consequences of his actions would last forever, his life was not entirely bound up by them. Hubacek’s punishment is a thousand miles from the unblinking eye of Twitter, where everyone is always the worst thing they’ve ever done.

The solution to the problem of public shamings, then, is not to eliminate shame altogether, as Ronson seems to hint—nor is the solution to eliminate shamings as such. Dante and Poe both show us that shame has an important role to play in the development of personal virtue, and perhaps the example of Hubacek suggests that, within certain limits, even public shame can be productive. However, it is imperative that we move shame off the internet, or at least off the public internet. The Twitter feeding frenzy serves little purpose beyond satiating the bloodlust of the virtual piranhas who engage in it—and even this satisfaction is temporary; once the corpse is stripped of its meat, they will be hungry again in no time. The righteousness one feels when participating in an online shaming is just that: a feeling. It is profoundly opposed to the development of virtue even in the person doing the shaming, because it allows them to assume that they are already virtuous. By critiquing him in person, on the other hand, Virgil risks Dante’s turning the criticism back on him. At the very least, he risks losing a relationship that is important to him.

Genuine shame—the kind of shame that can lead a person to deeper virtue—can thus come only from a relationship that is important to the person being shamed.

The relationship between Virgil and Dante is absolutely crucial to understanding the passage I quoted at the beginning of this chapter. God has chosen Virgil as Dante’s guide through hell and purgatory specifically because the pilgrim admires the poet and wishes, in some sense, to model his life after him. If he didn’t, Virgil’s disappointment in him wouldn’t carry much weight. Genuine shame—the kind of shame that can lead a person to deeper virtue—can thus come only from a relationship that is important to the person being shamed. One reason that Hubacek’s punishment worked as well as it did is that he was forced to reveal his actions to his community. No doubt most of the people who drove by him as he held his placard were strangers to him, but others were friends and acquaintances. Because he cared what they thought of him, he was able to reconstitute his story using his shame as a springboard to a new life. (What’s more, as Ronson reveals, even some strangers entered into a relationship with him, offering genuine encouragement.) It’s significant, then, that this shaming took place in the physical world, in an embodied way. Where it would have been easy to pile on Hubacek on Twitter, when his neighbors had to look at him, they must have been more inclined to treat him with compassion.

Note also that Dante’s feeling of shame is essentially coterminous with his asking for repentance: He finds himself “longing to beg for pardon and already / begging for pardon, not knowing that I did.” A shameless age is one that feels no need to repent or ask for pardon. When Donald Trump said, early in his campaign, that he had never asked God for forgiveness, he was announcing what many of us already knew: He is fundamentally shameless and thus, in many ways, the pure expression of the 21st-century American psyche. Our era largely disbelieves in grace, which puts us in a sticky situation: If there can be no grace, then we can’t admit that we need grace; thus, we tell ourselves that we (and our ideological allies) have nothing to confess. But on the other hand, we don’t want to extend grace to anyone outside of our in-group, and thus no matter how much they confess and repent, we continue to define them by the worst things they’ve done. Dante, on the other hand, experiences shame and repentance in a single motion. And forgiveness immediately follows, before Dante can even vocalize his desire for it. The role of shame is to drive us to repentance—but once we repent, our shame should disappear, replaced by grace.

The Importance of Community

Appropriate shaming, then, can take place only in small communities in which there is mutual respect and love. Christ understands this and gives instructions for Church discipline accordingly. If one member of the community sins against another member, the latter is to “go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone” (Matt. 18:15, NRSV)—just as Virgil rebukes Dante. But if the sinner doesn’t listen, the other person is to “take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses” (Matt. 18:16). After that, the matter goes to the congregation itself, and if the person still doesn’t feel ashamed and repent, he is to be treated “as a Gentile and a tax collector” (18:17)—that is, he is to be ejected from the community. The ejection seems to be a last-ditch effort to have the sinner repent; St. Paul adds that they are to “forgive and console him, so that he may not be overwhelmed by excessive sorrow” (2 Cor. 2:7). Shame leads to repentance, which leads to confession, which leads to forgiveness, which leads to reconciliation.

We shame other people because we love them and because we know we are in the same position they are, that we ourselves often need to be ashamed of the things we do.

This means that our shamings must always be motivated by a sincere desire for the repentance and reconciliation of the person being shamed. In other words, we don’t shame other people in order to feel righteous ourselves—“our righteous deeds,” after all, “are like a filthy cloth” (Isaiah 64:6). We shame other people because we love them and because we know we are in the same position they are, that we ourselves often need to be ashamed of the things we do. Shame, which is an essential tool in the development of human virtue, can be abused even within small communities, and in fact the current cultural aversion to shame is probably based on its abuses in churches. But shame can only be abused when it is not grounded in a loving relationship. This is why the shamings that take place every few weeks on Twitter and Facebook do no one any good: A useful process has been disconnected from its proper ends and become monstrous. Our goal should be to rehabilitate that process rather than destroying it altogether.

3 comments

Thomas McCullough

Thank you. I am informed and convinced, though I’d never gotten into shaming. I am troubled by the fact in this case and in so so many things else, virtue can only be made to thrive in small populations. I have a not-too-hopeful affection for the Front Porch view.

Brian

Your last section about community captures everything I was planning to write as I was reading all the previous sections…Bravo.

I’m pretty sure we’d be better off with replacing jails for youthful and first-time offenders with some sufficiently shame-based public punishments. We certainly couldn’t do any worse.

Colin Gillette

There are times, here on FPR, when I reflected on my own comments through a paradoxical shame/shamer lens. The impulse to leave comments without comsidering impact is difficult to resist. I watched some of Mark Zucherburg’s testimony before congress where he was questioned about using gambling algorithms to target the pleasure center of the human brain. I find the implication of something like gambling coding, coupled with our understanding of addiction in the brain, a staggering affair.

So, I appreciate the consequence of shame here. I am not always proud of my comments after some reflection, and by the time I realize it, the opportunity to reconcile has passed. This was a nice piece. Thank You.

Comments are closed.